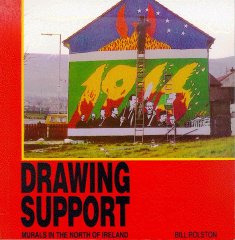

Drawing Support: Murals in the North of Ireland

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Murals: Drawing Support | |

| Introduction | |

| Loyalist murals | |

| Republican murals | |

| Murals: Sources, themes and process | |

| The murals of Mo Chara (Gerard Kelly) | |

| Conclusion: Conflict and propaganda | |

| Loyalist Murals | |

| King Billy | |

| Loyalist flags | |

| Red Hand of Ulster | |

| Historical events | |

| Military images | |

| Humorous and miscellaneous | |

| Republican Murals | |

| Hunger strike | |

| Military images | |

| Elections | |

| Historical and mythological | |

| Repression and resistance | |

| Prison | |

| International | |

| Gerard Kelly | |

| Nelson Mandela | |

* This section includes only 12 out of the 112 plates contained in the original publication.

It is easy to dismiss the political murals of the North of Ireland. Established artists and art historians do so on the grounds that they are not art. Political groups which do not share the politics displayed in the murals are likewise dismissive. Journalists and broadcasters regard murals merely as colourful backdrops and social scientists for the most part ignore them. Many people living outside the working class areas in which the murals are painted are unsympathetic, seeing the murals, on a par with graffiti, as vandalism. The Catholic church has little time for murals in its parishes; priests have painted out republican murals or sponsored the completion of alternative, religious murals. Finally, the legitimacy of the murals, and in particular republican murals, is denied by the state and its forces; the police and army frequently deface murals by smashing bottles of paint against them.

It may sound somewhat glib to argue that one reason for examining the political wall murals of the North of Ireland is that they exist. Yet that existence is indeed noteworthy. For almost a century on the loyalist side, and for more than a decade on the republican side they have been the products of a genuinely popular practice. As such, they provide a unique political insight. Through their murals both loyalists and republicans parade their ideologies publicly. The murals act, therefore, as a sort of barometer of political ideology. Not only do they articulate what republicanism or loyalism stand for in general, but, manifestly or otherwise, they reveal the current status of each of these political beliefs.

Loyalist murals have a long tradition, the first one having been painted in Belfast around 1908. Thus, by the time the Northern Ireland state was created in the 1920s, the tradition of mural painting was well established. After various upheavals, the state, with the Unionist Party in control, settled into a long period of relatively unchallenged dominance. This gave rise to a political cosiness that was evident, as much as anywhere, in the painting of murals.

The first mural painted in Belfast depicted the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, when Protestant King William III defeated Catholic King James II. The first loyalist mural in Derry, painted in the 1920s, repainted regularly since and still extant (see plate 1), depicts both the Battle of the Boyne and the lifting of the Siege of Derry by Williamite forces in 1689. Thus, although in the early days there was an apparently wide range of themes - the Battle of the Somme, the sinking of the Titanic - in fact the predominant theme of loyalist murals has been William's victory at the Boyne.

The reason for this is that the murals were - and for the most part still are - painted to coincide with the annual Twelfth of July commemoration of the Battle of the Boyne. The Twelfth celebrations were the high point of the unionist year. In working class areas kerbstones were painted, colourful arches erected, bunting hung and bonfires lit. The celebrations climaxed in a huge march organised by the Orange Order. All the classes of unionism marched side by side, but with the bourgeoisie in the lead, accompanied by bands and ornate banners.

The event is frequently depicted as a merely cultural one, a sort of unionist Mardi Gras, and is probably experienced as such by most participants. However, in a divided society nothing is simply cultural. Culture is highly politicised so that, by intention or otherwise, the Twelfth communicated important political messages. The events were triumphalist, sectional, sectarian. Nationalists could not join the Orange Order, even had they wished. At most they were reduced to spectators of this spectacle. In many ways this spoke volumes of their position in the Northern Ireland state, relegated to the margins economically, politically, socially and culturally. The Orange arches, erected over public roads, took on the significance of ancient yokes, reducing to the status of subjects all nationalists who could not avoid passing under them. The importance of these events was underlined by the fact that most major employers closed for 'the Twelfth fortnight'; everyone, unionist or otherwise, had no choice but to be on annual holiday.

Like the Twelfth ritual in general, mural painting became in effect a quasi-state activity, involving all the classes of unionism. At the unveiling of the mural some dignitary - a politician, judge, retired army officer or businessman-would speak briefly. The artisan painters of the mural - often coach painters or house painters -would be in proud attendance. The working class residents of the street would welcome enthusiastically their mural. And the cameras of the unionist press would preserve the moment for posterity.

Unionism had its divisions, but in the midst of this annual ritual, these were least obvious.

The problem for loyalist muralists was how to continue operating when the state came under siege. The civil rights campaign of the late 1960s and the British takeover of the 1970s and 1980s left Northern Ireland without a parliament. The mural painters faced the stark dilemma of painting monuments to the state in the absence of unionist control over the state. One solution to the dilemma was to cease painting and repainting murals; the number of loyalist murals declined drastically.

Another solution was to search for new themes related to unionist ideals in a less than ideal political situation. The latter option was difficult. How could one display visually the value of opposing British policies in the name of remaining British? What could be the symbols of such a schizophrenic message? One way was to revert to inanimate symbols; flags and Red Hand of Ulster motifs became common. Technically competent as these murals were, they lacked any depiction of human beings. Their heraldic grandeur displayed not so much assurance as rigidity in the face of rapid social change.

One other innovative approach was to turn to comic murals - for example, the Pope brandishing the scarf of a loyalist football team (see plate 37) - but these were hardly the stuff of profound statements of political identity. This is no surprise in a situation where that identity had been seriously called into question by political developments.

The mid-1980s saw a partial revival of loyalist murals m response to the signing of the Anglo-Irish Agreement in November 1985. In line with unionist indignation over what they perceived as a sell-out to Dublin, these murals contained highly militaristic images - men wearing balaclavas and firing weapons. Given loyalism's traditional willingness to engage m armed activities, the relative lack of such images prior to the mid-1980s is noteworthy. But it was not just the content of the murals which had changed radically; so had the mural painters. No longer the artisans of previous years, the modern loyalist mural painters were young men with more militant politics. Their murals were thus anathema to old-style mural painters who saw the new murals as sectarian in a way their own never were. Unlike the old, the new murals are intentionally anti-nationalist and anti-Catholic. The sinister images are threatening, and are meant to be.

Currently loyalist murals fall into 6 categories. The King Billy murals (see plates 1 to 8) still exist, some old, some new, some ornate, some naïve.

Flags and other inanimate depictions make up the second category. The flags most often painted (see plates 9 to 14) are the Union Jack, the Ulster Flag and the Scottish flag, the flag of St. Andrew. On one occasion (see plate 14) the Canadian and Australian flags appeared, in a desperate internationalist reference to unionist emigres in the 'Old Commonwealth'. The Red Hand (see plates 15 to 18) is a traditional symbol for both nationalists and unionists in the North. In loyalist murals it is sometimes shown in a traditional form, erect and dripping blood. Ingenuity also allows it to be shown protecting Northern Ireland (see plate 15), imprisoned in barbed wire (see plate 16), clenched defiantly into a fist (see plate 17), and sprouting feet to dance insultingly on the Irish tricolour (see plate 18).

Historical themes (see plates 19 to 28) also figure, especially when an important anniversary occurs. Thus the 75th anniversary of the founding of the Ulster Volunteer Force which later, as the Ulster Division, was decimated at the Battle of the Somme, led to a number of murals in the late 1980s (see plates 19 to 25). Of course, the traditional focus on the events of 1688 to 1691 also occurs from time to time (see plates 26 to 28).

As was said earlier, there has been a proliferation of military images since the mid-1980s (see plates 29 to 36), often crude, though sometimes ornate. Rarely do these depict any particular military operation, the notable exception being the attack by Michael Stone on mourners at the funeral of the three IRA members killed by the SAS in Gibraltar in March 1988 (see plate 36).

Memorials have a marginal place in loyalist murals, the only two shown here being to the two British army corporals killed at a republican funeral in March 1988 (see plate 44) and to George Seawright, a fiery loyalist politician killed by the Irish People's Liberation Organisation in 1987 (see plate 45).

Finally, a number of humorous, cartoon-style murals appear from time to time, often advertising a local marching band (see plates 39,40 and 46). Bulldogs seem to be popular (an allusion to the British connection), but cats, mice and rabbits feature also. While the depiction of the cartoon dog Spike in a loyalist band member's uniform threatening Tom who is wearing a scarf of a Celtic football club supporter is original and witty (see plate 43), these humourous murals are sometimes politically obscure. What, for example, could a passing observer make of loyalism if the only statement they were able to see was that of a rabbit in a uniform advertising Gertrude Star Flute Band? (see plate 46).

Nationalists traditionally did not paint murals. This fact alone is indicative of their relationship to the unionist state. Confined to lower status, greater poverty and higher unemployment, their culture became as ghettoised as they were. A vibrant culture existed, especially in relation to Gaelic sports, and Irish dancing, language and music, but it took place in the private space of church halls and sports grounds owned by the Gaelic Athletic Association. It was much more contained than the expansionist unionist culture of the Twelfth of July. There was safety in this confinement, but it was also systematically enforced by the state. No nationalist group could have succeeded in marching through the centre of towns as the Orange Order did. Gaelic sports results, unlike the more unionist sports such as soccer, were not read out on radio and television broadcasts. And the Irish language was not encouraged in any way by the state. Painting murals was not a civic duty for nationalists; more, it would have led to severe harassment by the armed police of the unionist state.

The emergence of murals on the nationalist side dates from the hunger strike carried out by republican prisoners in 1981 in pursuit of their demand for political prisoner status. This hunger strike came at the end of a five year campaign during which republican prisoners, refusing to wear prison uniform, were clothed only in blankets or towels. Graffiti in support of the blanket protesters, as they were known, increased at the end of the 1970s. By the time of the 1981 hunger strike these graffiti became ornate, accompanied by flags, coffins, and 'H' to depict H-Blocks, the cellular prison where the blanket protest and hunger strike occurred. It was a logical step from the ornate graffiti to the first murals.

In the spring and summer of 1981 hundreds of murals were painted. The two main themes taken up were the hunger strike itself and the armed struggle of the IRA. The latter theme is noteworthy. It could have been possible to represent the hunger strike solely in humanitarian terms. Muralists could have avoided referring to the IRA campaign in the hope of attracting more sympathy to the plight of the prisoners. In fact this did not happen. From the very beginning, unlike in the case of the loyalist murals, contemporary military images were prominent in republican murals.

With the hunger strike over and the immediate incentive gone, it might have been expected that republicans would have ceased painting murals. But they continued. A boost was given by Sinn Fein's decision to contest elections. Previously republicans had either refused to participate in elections in the North, or, if elected, had refused to take their seats. But during his hunger strike Bobby Sands, the first prisoner to commence the hunger strike and eventually the first to die, had been elected to the British parliament and Sinn Fein decided that there was electoral support to be tapped. As they began to run with great success in electoral contests, republican muralists had a reason to continue painting. Election murals were more impressive, and probably more effective, than posters.

Once that opening was made, murals appeared on the whole range of themes dear to republicans military action, protest against repression, prison conditions, media censorship or Britain's continued hold on Ireland in general, historical events and figures in Ireland, and murals identifying with anti-imperialist struggles taking place elsewhere in the world.

The republican murals pictured here thus fall into six categories. First are those murals which grew out of the blanket protest and hunger strike of 1981 (plates 47 to 64). Included are examples of the ornate graffiti (see plates 47 and 48) and the first murals painted (see plates 49 and 50), as well as a number of murals depicting the blanket protest itself (see plates 49 and 50,53 and 55). In the blanket protest murals, the prisoner was sometimes depicted as victim, sometimes as defiant, rising up and breaking the H-Block system. The murals relating to the hunger strike took a number of approaches - depicting the first hunger striker, Bobby Sands (see plate 51), all the hunger strikers together (see plate 52), representing what was called 'the conveyor belt of justice', with the republican prisoner processed from arrest, through beating during interrogation, non-jury courts and finally, on the blanket, refusing to be termed anything other than a political prisoner (see plates 54 and 56). Religious imagery was sometimes prominent (see plates 57 and 58), although not as frequent as some commentators state. Secular imagery was more common, and included the firing party firing a volley of shots over the coffin of the dead hunger striker (see plate 59), the phoenix rising from the flames (see plate 60), the lark in barbed wire, an image taken from the prison writings of Bobby Sands (see plate 61), and flags (see plate 62). The Irish tricolour and the Starry Plough of James Connolly's Irish Citizen Army, one of the groups which participated in the 1916 Rising, were the most frequently used flags, with the flag of the Na Fianna Éireann, the youth section of the IRA - an orange sunburst - making an appearance from time to time. The loyalist practice of depicting flags standing alone in all their heraldic splendour was rarely mimicked on the republican side.

Military images have been important in republican murals since the beginning (see plates 65 to 78). Sometimes particular events are depicted, such as the IRA operation which left 18 paratroopers dead in South Down in July 1979 (see plate 65). More often the murals depict fictional IRA members in action or merely posing, brandishing weapons. Frequently the IRA members are masked, making them indistinguishable from their loyalist counterparts on the walls, were it not for the surrounding imagery of flags and other such symbols. Memorials to IRA members killed in action have also been common, either to one specific IRA member (see plate 78), or a roll of honour for the dead from one specific area or town (see plates 75 and 76).

Elections constitute the third area of republican murals (see plates 79 to 81), allowing the muralists to take up themes which until that time had often been regarded as tangential, even diversionary, in republican circles.

Historical and mythological themes have been less frequent than might be expected (see plates 82 to 84). Thus depictions of James Connolly (see plate 82) and Patrick Pearse (see plate 83), both signatories of the Proclamation of Independence in 1916 are relatively uncommon. On the other hand, celtic imagery has been central in some of the most spectacular of the republican murals (see plate 84).

The issue of repression has given scope to republican muralists, whether specific instances of repression -such as the killing of civilians by plastic bullets (see plates 85 and 86) - or the general issue of the British presence in Ireland (see plates 87 and 88). On this last point, Joe Coyle's impressive analogy between the myth of Sisyphus and the British attempt to control Ireland (see plate 87) is both original and impressive. The resistance to repression is also considered (see plates 89 and 90), as is the experience of republican prisoners (see plates 91 and 92).

Finally, the struggle of republicans in Ireland has been compared to that of people elsewhere in the world (see plates 93 to 97). Political events in Palestine and Namibia (see plates 93 to 95), Russia and Cuba (see plate 96), and indeed the experience of minority women on all continents (see plate 97) have been central themes in a number of republican murals.

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||