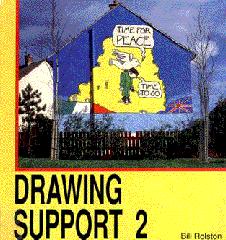

Drawing Support 2: Murals of War and Peace

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Introduction | |

| The Story so Far | |

| The Story Continues: Loyalist Murals | |

| Republican Murals in the 1990s | |

| 25 Years On: The Peace Process | |

| Ceasefire | |

| Murals: The Future | |

| Loyalists: | |

| King Billy | |

| Flags | |

| Red Hand of Ulster | |

| Military | |

| Memorial | |

| Prisoners | |

| Historical | |

| Humorous | |

| Republicans: | |

| Military | |

| Prisoners | |

| Repression / Resistance | |

| Elections | |

| International | |

| Peace Process | |

| Ceasefire | |

| The Future? | |

* This section includes only 14 out of the 112 plates contained in the original publication.

The tradition of mural painting in the North of Ireland is almost a century old. Beginning around 1908, loyalist artisans - coach painters, house painters, etc. - began to paint large outdoor murals each July. The timing was no accident; the murals were part of the annual celebrations of the Battle of the Boyne, one of a series of battles for the English throne between King James II and his son-in-law, Prince William of Orange. The battle took place on July 1, but with subsequent changes in the calendar, was celebrated in later years on July 12, known as "the Twelfth". The annual celebrations involved marches, flags, banners, bunting - and murals.

The victory of King William III (King Billy, as he is known) ushered in a period of consolidated British rule in Ireland, which included the "Protestant ascendancy". A key element in this ascendancy was the existence of "penal laws" whose purpose was the containment of the Catholic and Presbyterian populations of Ireland. The later incorporation of Presbyterians through the Act of Union of 1800 (which established the United Kingdom of Britain and Ireland) left the Catholics of Ireland at the bottom of the social hierarchy.

The annual celebration on the Twelfth was redolent with all these historical memories of victory and defeat. The significance of the celebration increased with the establishment of the Northern Ireland state following partition in 1920. The ritual became not merely a reaffirmation of unionist identity, but of a new variant in the Protestant ascendancy, a state ruled by one party and founded on the exclusion of a large minority of the population, the nationalists. Where the state's first prime minister could boast of having "a Protestant parliament and a Protestant state", marching, flying flags and painting murals took on extra significance. They became in effect a civic duty, recognised and legitimised as such by the state and its governing party.

Given their exclusion, nationalists did not paint murals. Their culture was marginalised, relegated to the private spaces of Catholic church halls, Gaelic sports fields, and private clubs. Nationalist opposition to partition took a number of forms, most obviously the sporadic military campaign of the Irish Republican Army (IRA). But the streets and public places were unionist. Republicans had less freedom to march and fly flags; they did not paint murals.

That situation changed with the hunger strike of 1981. Republican prisoners protested at the loss of "special category status", and eventually ten of them died. Nationalists and republicans took to the streets in support of the prisoners; huge marches took place and young nationalists began "drawing support" for the hunger strikers on the walls. The republican mural tradition was born.

With the end of the hunger strike, republican mural artists found other themes - the electoral strategy of Sinn Fein (the republican party), international comparisons, media censorship, etc. The new-found confidence of republicanism was symbolised in many ways, not least the manner in which they now claimed public space through marches and mural painting. The range of themes and styles evident in the murals is a striking illustration of this confidence.

By the 1980s unionism was less confident than it had been. Although militant loyalists engaged in a military campaign against nationalists and republicans, it was clear that the old unionist certainties were under siege. Again, the murals provided a window into the changed mentality. King Billy murals became less frequent, and in their stead were depictions of flags and other inanimate symbols. From the mid-1980s on, unionist and loyalist opposition to the Anglo-Irish Agreement left its mark on the walls, with the proliferation of stark military images.

The Story Continues: Loyalist Murals

Drawing Support: Murals in the North of Ireland charted and documented this story up to the summer of 1992. Mural painters on both sides continued to paint murals on the same themes after that date.

Given the centrality of King Billy, it appears paradoxical that his image was so uncommon in loyalist murals in the 1990s. Although new images of King Billy crossing the Boyne appeared from time to time (see plates 1-3), there were fewer such images overall. Moreover, some were m advanced stages of decay, pointing to the failure of some communities to maintain the tradition of re-touching the paintings prior to each Twelfth. It would be possible to exaggerate the significance of this decline. All the same, it does appear to be highly symbolic of a crisis in loyalist identity.

The crisis is starkly revealed in the Fountain area of Derry, the last Protestant working class enclave on the city side of the River Foyle. Here existed the oldest extant King Billy, painted and repainted for 70 years by three generations of the Jackson family. In the 1970s, when the area was being redeveloped, the Northern Ireland Housing Executive paid for the removal and reassembly of the wall and its mural. In 1994. the wall collapsed. Shortly before it did, a very different "King Billy" appeared briefly nearby (see plate 4). It portrayed a loyalist killer as King Billy. Michael Stone had attacked a republican funeral in Belfast in March 1988 with grenades and a handgun. He killed three mourners who had pursued him, before being rescued by the police. His action gained him hero status with many loyalists, including, one presumes, those who painted the Derry mural. But in 1990, Bobby Jackson, then 63 years old, articulated his disdain for such paramilitary murals and the young loyalists who painted them.

"I don't like them at all because they're very political and it seems as if there's death about the town and destruction more than anything else. There's nothing beautiful about them. It's always something political. They can't think about their own town; they've lost out on history. It's a very sad thing."[1]

In this view, history is counterposed to politics and culture excludes militarism.[2]

Often the symbols that now graced the walls where King Billy used to have undisputed prominence were of inanimate objects. It was often possible to see where the mural painter (and indeed the group to which he owed allegiance) stood on the spectrum between British identity and Ulster identity. The Union Jack, the flag of the Union, could stand on its own (see plate 5), revealing a traditional British identity; alternatively, there might be no Union flag at all, depicting a more hard-line, Ulster independence attitude (see plate 6). But more often than not, the flag murals stated that the Union of England, Scotland (as represented by the blue and white flag of St. Andrew) and Northern Ireland was worth fighting for (see plate 7). Alongside the flags were emblems, insignia, etc; in one mural the coat of arms of the City of Derry appeared, showing a skeleton representing the experience of the Siege of Derry in 1689 (see plate 8).

The Red Hand of Ulster also figured prominently, whether traditionally represented (see plate 9), or clenched in a fist, a symbol of the UFF, Ulster Freedom Fighters (see plate 10), or encircled in barbed wire, the preferred depiction of the LPA, Loyalist Prisoners' Association (see plate 11). The Red Hand could also appear with other heraldic devices (see plate 12).

The most noteworthy fact about these murals depicting inanimate symbols was the stark absence of human beings. It was as if loyalist mural painters no longer knew where loyalist people fitted. Moreover, the flags, shields, etc. seemed sure, indisputable, immovable. Yet the very robustness of this representation again disguises an underlying identity problem. These murals protest their confidence too much. As James Hawthorne, then Controller of BBC Northern Ireland put it:

"The more the majority - or at least the highly loyal section of it - waves the Union flag and talks of loyalty, the more it strives to cover up its identity problem."[3]

Much less ambivalent were the murals which display members of loyalist military organisations, primarily the UFF (Ulster Freedom Fighters), the UVF (Ulster Volunteer Force), and the RHC (Red Hand Commando). Prior to the Anglo-Irish Agreement of November 1985 there were relatively few such murals, but each summer afterwards they appeared regularly. This change accurately reflects the rearmament of loyalist groups in the late 1980s as a result of a large shipment of guns from South Africa, arranged by a British agent within loyalism, Brian Nelson. By the early 1990s loyalists were killing more people than republicans were, and military imagery was the most common theme in loyalist murals. Balaclavas and automatic weapons abounded, whether the military men were shown in action (see plates 13-18) or posing with their weapons (see plates 19-22). Sometimes the weapons could stand alone as mute testimony to loyalist military action (see plate 23). These military murals did not obviously reveal the purpose of loyalist military action, nor against whom the weapons were directed. There was no hint that during "the troubles" overall loyalists killed more civilians than republicans did, or that by the 1990s they were killing more people each year than republicans were, despite official assertions of republicanism as the main problem.4 But, to the nationalist or republican potentially at the receiving end of loyalist bullets, these murals were often sinister or threatening. And every now and again, the threat was spelt out. One mural in effect espoused 'ethnic cleansing'; "There is no such thing as a nationalist area of Northern Ireland, only areas temporarily occupied by nationalists" (see plate 24).

Among the military murals were also memorials to fellow members who "died in action" (see plates 25-27); less common were murals alluding to the comrades who were still alive, but imprisoned (see plates 28, 29).

Historical events and references were highlighted from time to time, but, unlike in the 1980s, there were no new murals depicting the Siege of Derry (1689) or the Battle of the Somme (1916). Instead, there were references to the original UVF (1912) and the B-Specials, a paramilitary loyalist police force of the unionist state between 1921 and 1969 (see plate 30). One such mural was part of a much larger complex of inter-related murals on the Newtownards Road in East Belfast. It depicts a B-Special and a member of the UDR, Ulster Defence Regiment, the successor to the B-Specials and later merged with the Royal Irish Rangers, another British army regiment - "Ulster's past defenders" (see plate 31). The mural to the right of this contains the statement: "Our message to the Irish is simple: hands off Ulster. Irish out. The Ulster conflict is about nationality". On the right of this is what has been to date the most astonishing image in a loyalist mural; behind a member of the East Belfast Brigade of the UDA (Ulster Defence Association), "Ulster's present day defenders", is "Cuchulainn, ancient defender of Ulster from Irish attacks over 2000 years ago" (see plate 32).

The apparent incongruity of the Cuchulamnn image is striking. It is an exact reproduction of the bronze statue sculpted in 1911 by Oliver Sheppard, which later came to stand as the symbol par excellence of the nationalist Rising at Easter 1916. Cuchulainn's stand against the invading army of Queen Mebh of Connacht was seen by nationalists as representing the desperate gesture of the republican and socialist revolutionaries who declared a republic in the face of overwhelming odds. The statue came to occupy pride of place in the General Post Office in Dublin, which had been the headquarters of the insurgents.

Why then should such a symbol ever end up on a loyalist wall in East Belfast? The answer is in the attempt to create a history for unionists at least as ancient as that traditionally claimed by nationalists.[5] This attempt rested on the centrality of the Cruithin, or Picts, the pre-Celtic inhabitants of the north-east of Ireland and the south-west of Scotland. The Cruithin's power waned as the Celts, who had arrived in Ireland from continental Europe, expanded from the south and west of Ireland. Queen Mebh's attack on Ulster and Cuchulainn's defence were thus easily reinterpreted. Mebh was a Celt, Cuchulainn a Cruithin. Cuchulainn thus came to be seen as m effect the first UDA man, defending Ulster against the marauders from 'the south'.

The revisionist history has never been widely accepted in unionist circles, particularly among the more respectable and middle class Ulster Unionist Party, UUP. As a political symbol, Cuchulainn the loyalist seems to more easily represent the secessionist proposal of an "independent Ulster" espoused from time to time by the UDA, rather than the desire to integrate fully with Britain, a policy dear to the UUP.

Finally, there is a category of loyalist murals which are humorous in content. Such murals derive their iconography less from loyalism or Protestantism than from cartoons and popular culture; thus in Ballymena a loyalist Bart Simpson proudly stands on the neck of a rat with the head of Gerry Adams, President of Sinn Fein (see plate 33). Usually painted by young men associated with loyalist marching bands, one such mural alluded to the fact that the band concerned was barred from marching because of its drunken behaviour on a previous occasion (see plate 34).

Republican Murals in the 1990s

Despite its origins in a prison hunger strike, an event which could have been depicted solely in humanitarian terms, the republican mural tradition had from the start refused to distance itself from the reason the prisoners had ended up in prison. Murals portraying the "armed struggle" were common from 1981 on, but were less so in the 1990s. Central to these murals were the actions and personnel. of the IRA (see plate 35). IRA men were depicted posing with their weapons or in action (see plates 36, 37). Often the weapons themselves came to stand for the military activity, whether the "barrack busters" of South Armagh, improvised from metal propane gas containers (see plate 38) or more conventional weapons. In one case, the words of the republican slogan "Tiocfaidh ar la" (our day will come) were arranged in the form of an armalite (see plate 39). Memorials to fallen comrades also came into this genre (see plate 40).

The prison issue did not reach any similar crisis at any point after the conclusion of the 1981 hunger strike. Despite the mass prison breakout in 1983 and the festering issue of segregation between loyalist and republican prisoners in the 1980s and early 1990s, to all intents and purposes the hunger strike achieved most of the republican demands. That said, the continuation of "armed struggle" meant there was a constant supply of new recruits to the prisons to join those republicans already there on long and indeterminate sentences. In that situation, there were occasional reminders in the murals that people should not forget the prisoners as well as references back to previous prison issues, such as the 1981 hunger strike (see plate 41) and the case of Tom Williams (see plate 42). Williams had been executed in 1942 and his body buried in Crumlin Road prison, Belfast. By the 1990s there was a campaign for the release of his body from the prison yard for reburial in a republican grave.

Although the political aspirations and ideology of republicanism were spelt out in murals, for the most part this was not the case in the "armed struggle" murals. It was left to another set of murals on the general theme of repression and resistance to articulate republican aspirations and demands. Opposition to the presence and activities of the British Army, including its Northern Ireland regiment, the UDR, was paramount (see plates 43, 44). Blatant acts of repression, such as the shooting dead of 14 civilians by the Paratroop Regiment during a peaceful civil rights march in Derry in 1972 (see plate 45), were addressed. In a more contemporary reference, as overwhelming evidence mounted in the 1990s of collusion between elements of the British forces and loyalist assassination squads, the issue was raised on walls (see plates 46,47). A notorious case of collusion was that of Brian Nelson, a senior intelligence officer in the UDA who was also an operative for British intelligence for ten years. As well as successfully setting up a number of republicans for assassination, he was instrumental in arranging the shipment of weapons supplied clandestinely by the South African forces for use by loyalists (see plate 48).

Overall, as numerous murals declared, the ultimate aim of republicanism was "Brits Out" and "free Ireland" (see plates 49-52). The demands could be referred to directly, or obliquely, as in the reference to Cuchulainn, alluding not only to the Easter Rising of 1916 but also to the continuing willingness of republicans to take on overwhelming odds in the struggle for independence (see plate 53). From then to now, the murals inferred, the struggle continued in various ways, including the successful attempt, after many years of failure, of republican marchers from West Belfast to march to the centre of their city (see plate 54).

Republicans also involved themselves with some measure of success in elections. Murals urging people to "Vote Sinn Fein" were often humorous and drew on many sources (see plates 55-57), including the most unlikely one of the paintings of Norwegian artist Edvard Munch (see plate 58).

Finally, the existence of anti-imperialist and democratic struggles elsewhere was a source of inspiration to republican muralists. Where in the 1980s there had been references to South Africa, and Palestine, in the 1990s it was Euskadi and Mexico (see plates 59, 60). Nicaragua figured in a mural in the centre of Perry (see plate 61). It involved the collaboration of three muralists from Managua, Nicaragua, and three from Derry (Doire in Gaelic). More generally, another Derry mural took the words of South American guerrilla priest Camilo Torres as the central message in a powerful and controversial image (see plate 62).

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||