CAIN Web Service

CAIN Web Service

'Republicanism - Part 2: 1922-1966',

by Republican Education Department (August 1972)

[CAIN_Home]

[Key_Events]

[Key_Issues]

[CONFLICT_BACKGROUND]

BACKGROUND:

[Acronyms]

[Glossary]

[NI Society]

[Articles]

[Chronologies]

[People]

[Organisations]

[CAIN_Bibliography]

[Other_Bibliographies]

[Research]

[Photographs]

[Symbols]

[Murals]

[Posters]

[Maps]

[Internet]

Text: Republican Education Department ... Page Compiled: Brendan Lynn

PART 2

REPUBLICANISM

1922 to 1966

REPSOL No.10

Republican Education Department, August 1972

Front cover [above] shows a party of the anti-Treaty I.R.A. on patrol in Dublin, 1922.

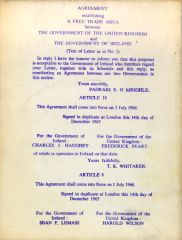

Back cover [right] shows part of the 1966 Free Trade Agreement between the U.K. and the 26 Counties with the signatures of some of those who were on the Irish side for the Treaty.

Back cover [right] shows part of the 1966 Free Trade Agreement between the U.K. and the 26 Counties with the signatures of some of those who were on the Irish side for the Treaty.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1922 was hailed at that time as a stepping stone to a Republic. It, in fact, became as time went on, a surer means for Britain to retain her hold on Ireland. British political and economic dominance of Ireland, North and South, was never endangered by the 1922 Treaty. They had to find new methods to retain control in the 26 Counties from that time. The culmination of the attempts by Britain and the Pro-British politicians to place all Ireland more firmly under British control was the signing of the Anglo-Irish Free Trade Agreement, 1966.

The pious platitudes and patriotic rhetoric that the Irish signatories of the Free Trade Agreement have been mouthing over the past few years, when contrasted with their deeds, can be seen for what it really is - mouth fighting - to confuse and fool the people while the politicians, Lynch, Cosgrave, Haughey, Hillery, Boland and Blaney sell the country.

REPUBLICANISM - PART 2 CHARTS THE SELLOUT

FROM 1922-1966

REPUBLICAN MANUAL OF EDUCATION

PART 2: HISTORICAL

FROM THE TREATY TO 1932

FIANNA FAIL IN OFFICE

NEO-COLONIALISM - 195Os-6Os

THE LESSONS OF HISTORY

REPUBLICAN MANUAL OF EDUCATION

PART 2: HISTORICAL

REAMHRA

"Republicanism" is the 2nd Part of an edited and revised Historical Education Document first issued in 1966. The first Part dealing with the period 1790-1922 has already been published, Part 2 deals with the period 1922-1966. It is intended soon to publish a pamphlet dealing with the changes and development in Ireland and the Republican Movement over the years 1966-1972.

"Republicanism" Parts 1 and 2 are primarily intended to give people an idea of the development of Republicanism and to act as a starter of a more thorough study of Irish history.

REPSOL PAMPHLETS are published by Republican Education Department.

PRINTED by Clo Naisiunta, 30 Gardiner Place.

"Part 2: Historical", is no. 10 of a series of pamphlets being published by Republican Educational Department.

A REPSOL PAMPHLET copyright August 1972.

CUMANN na nGael and FIANNA FAIL,

FROM THE TREATY TO 1932.

The Cumann na nGael Government that ruled the Free State from 1922 to 1932 represented the most pro-imperialist elements in the country, whose economic interests called for free trade with Britain and close political and cultural ties with her. These were:-

a) Business interests bound up with commerce, trade and merchandise, importing and exporting, who made money out of the necessity for Ireland to import the bulk of the manufactured goods she consumed from Britain.

b) Business interests bound up with banking, finance and insurance, who made their money from the channeling of Irish savings abroad, particularly in the various colonies of the British empire, where they could make a higher rate of interest than if they were invested in Ireland, however productive they might be in other ways at home.

c) The big farmers, "ranchers", who made their money by selling cattle to Britain and who needed free access to the British market for this.

d) Business interests bound up with brewing and distilling, at that time, in the early 1920s, the largest single sector of industry in the Twenty-Six Counties who made much of their money on the basis of a large export trade they had developed with Britain and who did not fear competition from British rivals on the Irish market (e.g. Guinness).

e) Sections of the higher professional groups in the cities and towns, people who were tied by sentiment or economic interest to the old Ascendancy.

An analysis of the social background of the Cumann na nGael T.D.s and Senators, of the people and areas that voted for them in elections and of the speeches and policy declarations that they made, will show that this picture of the particular social groups they drew their strongest support from and in whose interests they governed is broadly a correct one. Today, broadly similar sectors of the community support the Fine Gael Party and provide it with its leadership and policies.

The political and economic measures carried out by the Cosgrave Government in the 1920s were such as to serve the interests of these groups in the population primarily. These interests were frequently opposed to those of the mass of the people in the towns and countryside however. The workers in the towns in the 1920s wanted higher wages and better working conditions; they were badly hit by the mass unemployment and low wages imposed on the people in the aftermath of the Civil War and as a result of the World Slump, whose effects the Cosgrave Government’s policies could do nothing to mitigate.

The mass of the small farmers were discontented by the fact that they had got nothing as a result of the War of Independence which they had provided the backbone of the struggle in the countryside. They were insecure in their property; they had to pay millions of pounds a year in the form of land annuities to the Free State Government, which then passed them on to Britain as "compensation" to the landlords who had been bought out of the land which their ancestors had robbed from the people. Many of the small farmers and labourers to asked why the many big estates of the Midlands and Munster could not be divided up and given to the impoverished and landless men of the west and south.

As the 1920s passed, the workers, small farmers and rural labourers saw that the Cumann na Gael Government, with its wage cuts, unemployment and repression of republicans and trade unionists, and with its subservience to Britain in every field, was not a government with their interests at heart. Moreover, in 1925 a severe blow was dealt to the prestige of the Cosgrave Government by the Boundary Agreement, when the Twenty Six County Government agreed to accept the Border as it had been drawn under the Government of Ireland Act. Griffith and Collins had purported to regard the Free State as a "stepping stone" to the Republic and that the Boundary Commission agreed on under the Treaty would redraw the boundaries of the Six Counties, exclude Tyrone and Fermanagh etc. from the North, and make the Six Counties no longer viable as a separate state. But the Boundary Commission Report changed nothing, and in retrospect it seemed as if the Civil War had been fought to force partition on the people.

But due to the Provisional Government’s victory in the Civil War, power in the country south of the border was possessed by the Free State. The Free State controlled the army, the police and the civil service; they made the laws and were able to enforce them on those who didn’t want to obey in the area under their jurisdiction. In general those laws were passed either in the interests of Britain or of the pro-imperialist elements who held office in the Free State.

But during the 1920s more and more of the common people saw that the Free State was using its power against the people rather than for their benefit, in the interests of imperialism rather than of anti-imperialism. More and more began to look for an alternative political leadership to the Free State, an anti-imperialist leadership, which would put the interests of the men of no property and the small men first.

Two organisations existed by 1926 which might provide this alternative leadership and government - Fianna Fail and the I.R.A.

Fianna Fail, under De Valera’s leadership had been formed in 1926 after a split in Sinn Fein. The official Sinn Fein position on the Treaty was that the people had been confused and divided and that they must be won back to their allegiance to the Republic, and could express this allegiance by returning a majority of Sinn Fein candidates in a general election, as had happened in 1918. The remaining T.D.s of the Third Dail who did not accept the Treaty claimed de jure power and Sinn Fein gave allegiance to this body as being the legitimate successor of the government of the Republic proclaimed in 1919. It had, of course, no power to enforce its will or make laws that would be obeyed. This power was possessed by the Free State Government.

De Valera held that the only way to win a majority was to declare a willingness to go into the Dail as a minority and that there was no possibility of winning majority support for the long term programme - the Republic - without winning it first for a short term programme. The interests De Valera and his colleagues represented within Sinn Fein saw that the power possessed by the Free State could be used for their benefit, and so they Bet about the steps which would enable them to take power in the state into their own hands. De Valera left Sinn Fein and founded the Fianna Fail Party in 1926 and adopted a programme which they pledged themselves to implement if elected to a majority in the Free State Pail so that they could form a Government.

What interests did De Valera and his Fianna Fail colleagues represent?

They represented, so far as the leadership and policy-making section of Fianna Fail went, an important section of the business and manufacturing sector of the country, whose economic interests were opposed to those of the commercial, banking and ranchers sector that supported Cosgrave. Fianna Fail represented the small manufacturers and distributors who twenty years before, had supported Arthur Griffith’s old Sinn Fein, with its policy of protecting the home market against foreign competition in the interests of Irish manufacturers.

They did not want free trade with Britain - which the bankers, merchants, and ranchers who supported Cosgrave. They wanted a protected Home market which they could exploit; they wanted their own home manufactures to replace the imported goods from Britain which the Cosgrave Government did nothing to discourage. They were anti-imperialist to the extent that they wanted to oust British goods from as much of the economy as possible and replace them with goods manufactured in Ireland; they wanted a protected Irish industry with tariffs, quotas, duties and licenses, and the restriction of the free field British industry had had in Ireland since the Union.

They represented "property", but a significantly different section of it than did Cumann na nGael. Indeed the interests of these two sections of "property" were considerably antagonistic to one another. The replacement of imports by home manufacturers would injure the merchants and importers who supported the Free State. It might provoke retaliation from Britain which would injure the cattle trade that the ranchers depended on. It might lead to control of the investment of Irish capital in the empire, to use it instead to build up home industry, and this would injure the banks and the remnants of the ascendancy. Hence the hostility of Cosgrave and Co. to Fianna Fail reflected the conflict of interest between one section of business and another.

At the same time the ideas of industrialisation and economic development put forward by Fianna Fail in the interests of Irish industrialists would benefit the workers in the towns, give more jobs, reduce unemployment and enlarge the home market for the farmers. Hence they were likely to get the support of Labour in the urban areas, which in fact Fianna Fail did get. But it is important that the Fianna Fail programme was not a Labour programme and not put forward in the interests of Labour. It emanated from the small business elements who wanted the home market for themselves, who were anti-imperialist to the extent that they feared and were injured by the competition of British imports, but who wanted to make the maximum profit they could out of Irish workers and small farmers themselves.

The leadership of Fianna Fail was soon in the hands of "property"; license seekers and protection-seeking businessmen flocked to join Fianna Fail, were the major source of its funds, and dominated its councils. But this leadership of businessmen and aspiring businessmen was likely to compromise with imperialism when the struggle got such that they could only carry it on only by appealing to the radical sentiments of the "men of no property" for support. For to do that would be to threaten and endanger its own property interests.

The interests of the workers and small farmers, who had no reason to compromise with imperialism, for they had nothing to lose, was mainly represented by the late 1920s by the I.R.A., which had many thousands of members among the city workers and the small men of the countryside. But the I.R.A. was primarily a military force, the armed defenders of the Republic, ready to take up arms to re-establish the Republic when a suitable opportunity offered itself. During the ‘20s and ‘30s, although several attempts were made by the I.R.A. to give leadership on the political and economic front as well as the military, they were relatively unsuccessful; and Fianna Fail, led by a middle class leadership inevitably prone to compromise, captured the political leadership of the mass of the people in the countryside and were anti-imperialist, and who returned Fianna Fail as the major party in the Dail in the 1932 election.

The main attempt to give a social content to the cause of the Republic in the late 1920s and early 1930s was made by the I.R.A. on the land annuities question. These were the heavy payments which the farmers made direct to Britain through the Free State Government. The I.R.A. was intimately involved in the countryside agitation against payment of these land annuities by the farmers and in favour of their retention in Ireland.

When the Free State bailiffs and police came to collect the land annuities in the countryside, local republicans and I.R.A. units were frequently involved in physical resistance. But while supporting local economic agitations, the I.R.A. and republicans stopped short of direct involvement in political agitation. It was Fianna Fail that reaped the political benefit of the land agitation that had been initiated by the republicans. It was they who made the refusal to pay the land annuities to Britain a major plank in their platform in 1932 and Fianna Fail got the mass support of the people of the countryside in the 1932 election on the basis of their pledge to retain the land annuities in Ireland if they were returned to form a government.

Attempts were made also in the 1920s and early 1930s to closely identify the I.R.A. and the republican cause with that of the workers and trade unionists in the cities. Republicans were very active individually or as units in labour struggles, unemployed demonstrations and trade union organisation. An important development in this period was the growth of strong anti-Unionist sentiment among sections of the Orange working class of Belfast, under the impact of the unemployment and the anti-Labour policies of the Northern Government.

Large contingents of Belfast workers took part in the Bodenstown commemorations during the early 193Os; they were attracted by the social radicalism of the republican movement of those years, which brought the cause of the Republic down "from the clouds" and made it something that mattered in the fields and factories. At this time also there was considerable discussion on organising active republicans in the towns on an industrial basis rather than an area one, to make them more effective in identifying themselves with the problems and interests of the workers and trade unions; but no definite steps had been taken by the time Fianna Fail came to power in 1932 and the political situation changed.

The political problem was the overriding one for the republicans of this period. It was clear to all far-sighted republicans that Fianna Fail and the Fianna Fail leadership did not consist of the kind of people who would carry the anti-imperialist struggle to a conclusion, in either the political economic or military spheres. It was clear that while Fianna Fail was anti-imperialist on certain issues, its anti-imperialism would extend no further than what would serve the economic interests of the manufacturing middle class that dominated it, who would choose to compromise with imperialism when it came to the push rather than put forward the radical social and economic policies which alone would swing the support and enthusiasm of the mass of the people, farmers and workers, in favour of a resolute anti-imperialist struggle.

The prospect with Fianna Fail in office was of another compromise with Britain and abandonment of the struggle for a united independent Republic, except that this time the betrayal would be by the political leadership of the Irish manufacturers, De Valera and Lemass, rather than of the bankers, merchants and ranchers, Griffith and Cosgrave. But Fianna Fail were the only people on the scene who offered the people a practical possibility of ousting the oppressive Cosgrave Government; and in default of any viable alternative political movement the people were bound to support Fianna Fail.

Many attempts were also made during this period to find some solution to the problem of "politics" for republicans. This question was closely bound up with the question of the attitude of republicans to the Dail and the 26 County Government, and the army, police force and administration which this government possessed. Many republicans held that they should have no truck with the Twenty-Six County Government and should not take seats in the Twenty- Six County Dail as a minority. Others held that this meant that the Fianna Fail "compromisers" would be allowed to form a government and that they would be facilitated in doing a deal with imperialist because there would be nobody among their members or in their ranks who would keep them under pressure to oppose imperialism to the limit or to expose them.

The former held that "politics" as such were inherently corrupt and that Fianna Fail compromise with imperialism would be due basically to the fact that they had entered the Dail as a minority. The latter held that Fianna Fail would be prone to compromise with imperialism not because they had entered politics, as such, but because of the business and property interests Fianna Fail represented and served, and that a genuine republican party, based on and led by the "men of no property", with a disciplined structure and linked closely to the social struggles of the people, would be immune from such compromise and could enter the Dail and give effective political leadership to the people without being corrupted; they held that even if such a group were in a minority compared with Fianna Fail, its presence would put pressure on Fianna Fail to maintain a radical anti-imperialist line and it would be available to provide an alternative anti-imperialist leadership for the people if Fianna Fail did give way before imperialist pressure.

When it came to the general election of 1932 the former side held that the republicans and the I.R.A. should stand aside and give passive support to Fianna Fail in the general election, which in fact was what was done. The latter proposed that the republicans should put up candidates who were closely associated with the land annuity struggle and the labour movement, who would not have the interests of the manufacturers and business elements at heart as Fianna Fail had, and who would take their seats in the flail, putting pressure on the Fianna Fail Government to carry out a radical anti-imperialist policy and being ready in the wings to replace Fianna Fail as an alternative republican leadership if and when Fianna Fail started to compromise.

This debate between individuals and groups over policy dominated the republican movement for several years in various forms at this time. It was still going on in 1932 when Fianna Fail got the votes of enough people to make it the main party in the flail and De Valera assumed office.

The main features of this period are:

1) The attempt by republicans and the I.R.A. to associate themselves with the social and economic issues before the people by being active in the land annuity campaign and labour struggles. They had grasped the reasons for the failure of 1921 and the lesson of Mellowes.

2) The emergence of Fianna Fail as a party of the industrial middle class, anti-imperialist to a degree, hut prone to compromise because of its ties with business, using republican rhetoric and demagoguery to gain support and championing popular policies to a certain degree.

3) The failure of the republicans to give an effective political leadership to the people which would be an alternative to Fianna Fail and at the same time to put continual pressure on it to oppose imperialism, or else face exposure and replacement. This would have meant tackling the problem of forming a disciplined, incorruptible political movement that would be prepared to work as a minority within the Dail, until it gained enough support to make it a majority.

BOOK TO READ: There Will be Another Day - Peadar O’Donnell.

FIANNA FAIL IN OFFICE

- the development of 'Gombeen' nationalism;

the late 1930s and 1940s

Fianna Fail came to power in 1932 on a broadly anti-imperialist programme which had won the support of many of the workers and small farmers of the country. The main points of this programme were:

1) To protect Irish home manufacturers and the home market and develop Irish manufactures in substitute for imported goods from Britain. For this purpose the Control of Manufacturers Act was passed, making it unlawful for non-Irish nationals to hold more than 40% of the shares in newly formed companies and requiring that a majority of the members of boards of directors of companies should be Irish nationals.

2) To establish state industries in the power, manufacturing and transport sectors where private enterprise was unable or unwilling to do the job.

3) To retain the land annuities which the farmers paid to Britain through the Free State Government.

4) To abolish the Oath of Allegiance to the Crown which members of the Free State Dail had to take, to abolish the Governor-Generalship and the other trappings of Dominion status accepted by Cumann na nGael under the Treaty.

The bulk of this programme was in fact carried out during the 193Os, and in successive elections the majority of the people in the Twenty-Six Counties gave Fianna Fail an overall majority of votes cast. The first major step in carrying it out, however, the retention of the land annuities, resulted in vigorous British counter action. When the Dublin Government announced that it was under no moral obligation to pay the land Annuities and that it was going to retain them in future, the British Government retaliated by imposing penal duties on Irish exports to Britain, duties which hit the cattle trade and agriculture particularly hard, adding fuel thereby to the hatred which the ranchers felt for Fianna Fail and giving an impetus to the growth of the Blueshirt movement, which based its support primarily on the large farmers.

It is highly unlikely that the loss of the relatively small sum involved in the Land Annuities was the main cause of the British Government’s action. More likely was the aim of bringing the Fianna Fail Government to its knees as quickly as possible and teaching it the lesson that Britain could not be flouted with impunity.

The Economic War hit the cattle ranchers badly. Likewise the policy of protection of industry and the Fianna Fail policy of granting manufacturing licenses to its supporters to produce goods in Ireland which had previously been imported from Britain, hit the merchants, commercial and banking interests that had supported Cosgrave and Cumann na nGael. The ranchers and the merchants coalesced to’ form the Blueshirts, a Fascist organisation, modelled on Mussolini’s Blackshirts and the other Fascist movements on the continent, with the aim of overthrowing the Fianna Fail Government by violence if necessary, establishing a dictatorship and returning to the outright pro-imperialist policies of the Cosgrave era.

At that time, in the early 1930s, De Valera and Fianna Fail could not rely with very much confidence on the Irish Army and the Gardai, as these bodies had been formed by the Cumann na nGael Party and recruited from the Pro-Treaty side in the Civil War. Fianna Fail in its first years in office had in fact to turn to the I.R.A. and the Republicans for military support in countering the Blueshirt threat. De Valera gave the I.R.A. a free hand to deal with the Blueshirts, and the strength of the I.R.A. was undoubtedly the main factor responsible for containing the Blueshirt mobs and preventing the overthrow of the Government by the Cosgrave - O’Duffy - Dillon supporters of that time.

In the meantime, the Fianna Fail Government was building up its own support in the army and police force, establishing a political police loyal to De Valera, trying to win over to the Fianna Fail side as many republicans as possible by means of an efficient system of patronage and pensions for veterans of the War of Independence and consolidating its hold on the civil service. For it was clear that when the Blueshirts had been dealt with, the continued existence of such a powerful organised military force as the I.R.A., not under the control of the Government would constitute a threat to the Government’s monopoly of power in the State- a threat from the left, as the Blueshirts had been a threat from the right.

The existence of such a force as the I.R.A. meant that the Government could fear being pushed out of the way if compromised with imperialism, which it was inclined to do under the pressure of the Economic War.

At this juncture (1934) maximum unity was needed to put pressure on Fianna Fail and keep a united republican front against the Government. Instead a split occurred in the IRA, which was to have a disastrous impact on the cause of republicanism for several decades and from which that cause is only recovering today. One section of the I.R.A., led by Frank Ryan, urged that the I.R.A. and Republicans generally should involve themselves more in the economic and social struggles of the small farmers and workers, should forge organisational links with the Trade Unions and Labour Party under the aegis of a Republican Congress, and should expose Fianna Fail’s compromising policies in this way. The other, led by Moss Twomey and Sean McBride, urged that De Valera and Fianna Fail should be called on to declare the Republic, to amalgamate the I.R.A. with the Free State Army, and to march North to enforce the writ of the Republic by force in the Six Counties. As it was highly unlikely that De Valera would be willing to do this, the I.R.A. should then take on the task of expelling the British military forces itself.

This development played right into the hands of the Government and confused the forces of Republicanism which should have remained united at all costs in the work of exposing Fianna Fail and offering an alternative anti-imperialist policy to the Government’s on all fronts - social, economic, political and, if necessary military. Again, as had happened in 1921, different sections of Republicans latched on to different aspects of the national question and counterposed the economic struggle to the political, the political to the military, instead of realising that unity was the first essential, so that a united movement could take up with its full strength the economic, political or military sides of the struggle whenever one or other came to the fore with changing circumstances.

The main lesson of past republican failures was that the economic, political and military struggles against imperialism and its different aspects could not be divorced, that the vital need was for an organisation which could take an overall view, be able to analyse the changing character of imperialism as it changed its strategy from one of military domination to one of political pressure to one of economic penetration, in response to changing demands and circumstances, and be able to concentrate united energies on whichever aspect of the struggle was most appropriate at a given time.

With the anti-Fianna Fail forces divided, De Valera seized his opportunity, declared the I.R.A. an illegal organisation, and slammed down on its members with a battery of repressive laws (which had been originally used by the Cosgrave Government) and police measures. Those members of the I.R.A. who fanned the Republican Congress failed to obtain mass support; the people were dismayed and bewildered by the split which had given rise to it. The I.R.A. called upon De Valera to declare the Republic and attempt to enforce its laws in the North. De Valera replied that such an attempt would lead to another civil war between Irishmen, this time between Orange and Green. The I.R.A. went underground on being declared illegal and prepared to resume the war with Britain on its own when the opportunity offered, which seemed to come with the outbreak of the World War between Germany and Britain in 1939.

De Valera was now freed from an effective rival to Fianna Fail internally on the political and economic front and was in a position to compromise with imperialism without evoking mass discontent from the people, as the latter had no effective alternative political leadership to Fianna Fail.

Fianna Fail by the middle 1930s felt it had gone as far as it dared go in conflict with Britain. The manufacturers were satisfied - they had got a protected home market and several state companies were set up to develop industry which was not sufficiently profitable or demanded too large amounts of capital to attract private enterprise. The republican sentiment of many people was catered for by the abolition of the Oath of Allegiance and the trappings of dependence left over from the Treaty.

In 1937 De Valera brought in a new Constitution which asserted the de jure claim of the Dublin Government to sovereignty over the whole country, but which recognised the de facto position that that sovereignty could not be exercised in practice north of the Border. In an attempt to broaden the basis of his power De Valera sought an agreement with the Church (in the days of the Cosgrave Government Fianna Fail had been widely regarded by conservative church leaders as the party of Communism and anarchy) and incorporated clauses in his Constitution which recognised the "special position" of the Catholic Church as the faith of the majority of the people, and forbade divorce and contraception, even though the position of the Protestant Churches on these matters is different from that of the Catholic Church.

These clauses were inserted in the Constitution on the behest of certain members of the Hierarchy (though not of all) and they effectively discriminated against the views of the Protestant minority in the Twenty-Six Counties, as well, of course, as constituting a major barrier to unity with the Northern Protestants. The latter regarded these concessions by Fianna Fail to clerical opinion in the south as proof of the dominant role which they contended the Catholic Church would be bound to have in a united Ireland, when the Protestant position would have to give way to the Catholic on such issues.

Fianna Fail’s political and economic compromise was shown on two major issues -

1. Its failure to establish an independent currency and a Central Bank which would have effective power to control the volume of credit in the economy in accordance with the Government’s economic policy and

2. Its failure to control the export of Irish savings and capital from the country and to demand that the banks, insurance companies and owners of private capital should invest this in home industry and agriculture rather than in British and overseas projects.

Both of these measures would have entailed radical interference with the "rights" of large owners of capital in the national interest; they would have entailed restriction on the "right" of private investors to invest their capital where it would make them the maximum profit, even though it might be of little use to the national economy and the community as a whole. It would have angered even further the British Government, which was - and is - in a position to control Irish credit policy from the Bank of England and thus influence profoundly the internal economic policies of Irish Governments, and those economy benefits substantially by the investments in Britain of several hundred million pounds by Irish savings and foreign earnings.

These measures would have necessitated a far more radical interference with property interests and conflict with Britain than the property interests in charge of the Fianna Fail Government and policy were willing to contemplate. To have attempted them would have thrown the Government too much into the arms of the radical and republican elements in the population.

And so, having obtained for Irish manufacturers the right to exploit the Irish market, Fianna Fail decided it had gone as far as it could go; it sought a deal with Britain. It did not realise that there is no stopping short of complete independence; that there can be no resting at a half-way position of half-independence; that from there one can only progress or regress. For Fianna Fail the two-decade-long road of regress back into the United Kingdom had begun.

The deal Fianna Fail did with Britain was the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1938. In the political sphere this Agreement returned the naval bases of Berehaven, Haulbowline and Lough Swilly to Ireland (Britain had retained them under the Treaty). This did not call for much sacrifice on Britain’s part. It ensured her of Ireland’s neutrality in the coming conflict with Germany. If Britain had retained the bases Ireland would certainly have been involved in the conflict, and quite possibly on the German side. To have Ireland fight on Britain’s side would be too much to hope for as long as Partition existed; so the next best thing for Britain was a neutral Ireland; and this she obtained in this way. In the economic sphere the Agreement marked the end of the Economic War. Britain recognised the right of the Irish manufacturers to protect their home market - British goods had already been ousted from considerable sections of this market in any case; but Ireland guaranteed that British imports to Ireland would be given preference over those of other countries. Britain in turn lifted the penal duties on Irish cattle and allowed many Irish goods to be imported to Britain without duty.

At that time Britain wanted to do her utmost to ensure a good supply of Irish agricultural goods anyway, with the war impending; and she did not fear very much the competition of Irish manufactured exports on the British home market, as Irish manufacturers tended to confine themselves in the main to the Irish market and did not in general seek to develop significant outlets in Britain nor abroad, nor had they the capital to do so as long as they permitted unrestricted export of Irish savings and capital.

The political and economic sides of the Agreement, therefore, represented a compromise by the representatives of the Irish manufacturing middle class with British imperialism. The essential character of the relationship between the two countries - Ireland’s weakness and dependence, as against Britain’s strength and dominance, was likely henceforth to get gradually stronger and more powerful, while the forces working for political and economic independence within Ireland were likely to get weaker unless they could realign and reunite themselves.

In 1939, on the outbreak of War, the I.R.A. estimated that another opportunity had come, as had happened in the First War, to take advantage of England’s difficulties for the benefit of Ireland. The "Bombing Campaign" was organised in England, a campaign in which numbers of brave men gave their lives for their country. If England had been defeated in the War it would have been highly likely that an opportunity would have existed for winning the reunification of the country and ending Partition. But this did not occur.

The Fianna Fail Government that it could not presume to maintain its position as a neutral between Britain and Germany if it gave the I.R.A. a free hand. De Valera declared a state of emergency; the Offences Against the State Act was passed. Hundreds of republicans were interned without trial for the duration of the war. Many were tried before the Special Criminal Court and there were several judicial murders of republicans. Fianna Fail made every effort to smash the republican movement and, although it did not succeed, Fianna Fail emerged from the War in strong control of the country, having inflicted grievous blows on the organisation and personnel of the republican movement, which was still groping to find an effective policy whereby imperialism could be countered and the Fianna Fail Government’s policies could be effectively exposed before the people and their allegiance won for some alternative course.

In the period 1946-48 an attempt was made by some disillusioned members of Fianna Fail and some former republicans to provide a more radical political alternative to Fianna Fail. The Clann na Poblachta Party, led by Sean McBride was founded and got a considerable measure of support in some bye-elections and had several T.Ds elected to the Dail in the 1948 General Election. The main political planks of this new Party was to invite the Nationalist M.P.s from the Six Counties to take part in the proceedings of the Dublin Parliament. It used much "republican" rhetoric, but its leadership was firmly in the hands of middle class elements whose main unifying link was a common desire to get Fianna Fail out of office.

The new party was a mushroom growth, with no firm basis of popular support built up as a result of consistent championing of the needs of the workers and small farmers, and thus with no mass pressure from below to prevent the leadership selling out when they came within sight of the spoils of office.

It was with alacrity therefore that McBride and others led the new "republican" party into a coalition Government with the most reactionary party in the country, - Fine Gael, - on the defeat of Fianna Fail in the General election of 1948. McBride and other Clann na Poblachta leaders took office in the Coalition Government, where it was quite impossible for them to implement even such programme as they had, and the new party gradually fizzled out. Its fate was an object lesson of what would happen to those who sought to move from "the gun" into "politics" without the requisite political understanding, a disciplined organisation and incorruptible leadership that was not "middle class", and a basis of mass support won as a result of championing the economic and social needs of the people.

The leaders of the Labour Party also joined the Coalition Government and thus sacrificed the interests of the people they were supposed to represent for the sake of gratifying a barren hostility to Fianna Fail and to obtain political office for themselves. For in reality the period of the two Coalition Governments, 1948-51 and 1953-57, saw the country ruled in the interests of Fine Gael, which was the largest party and which therefore dominated the Coalition; the general pattern of legislation was conservative in the extreme, e.g. the abortive "Mother and Child Scheme".

To appease the "republican" rhetoric of Clann na Poblachta Fine Gael "proclaimed the Republic" in 1949 and withdrew from the Commonwealth. This was a "republic" of Twenty Six counties, and meant only a change of name from De Valera’s Free State. It was essentially a demagogic gesture and added not one jot or tittle to the territorial area or the power of the Twenty Six County State. Britain, however, retaliated even to this by passing another Government of Ireland Act (1949) which stated that the Six Counties could not cease to be part of the United Kingdom without the consent of the Six County Parliament. Even if the majority of the people there should vote to leave, they would not be allowed to as long as Unionists had a majority in Stormont.

THE LESSONS OF THIS PERIOD ARE:

1. The progressive character of the Fianna Fail programme of 1932, emphasising economic development and inevitably leading to a conflict with Britain. The inevitability of compromise on the part of the middle class manufacturing interests that provided the leadership of Fianna Fail under pressure from Britain unless an alternative republican leadership that had no such ties was available to take over the struggle instead.

2. The trend towards Fascism and dictatorship among the most pro-imperialist propertied interests - commerce, banking and the ranchers - when they were being hurt in their pockets by the policies of economic independence of Fianna Fail.

3. The failure of republicans to maintain unity when it was most needed in the early 1930s to keep up maximum, pressure on Fianna Fail and expose and prevent the trend to compromise among the propertied elements. The division of republicans into different sections, each taking up a different aspect of the anti-imperialist struggle, without any common strategy or leadership. The greater ease with which Britain and Fianna Fail as a result could deal with republicans and effectively exclude them from having a major influence on events.

4. The failure and unwillingness of Fianna Fail to tackle the problems of establishing an independent currency and credit system and to control the investment abroad of Irish capital, as this would have entailed a more radical interference with property interests than Fianna Fail was willing to undertake without mass pressure from below; and this could not emerge when the republicans were divided and weakened.

5. The reasons for the failure of the Clann na Poblachta attempt to provide a political alternative to Fianna Fail. Barren hostility to Fianna Fail and a "gimmicky" programme was no substitute for a genuine anti-imperialist policy that would be more convincing to the people than Fianna Fail’s. There was no mass popular basis, no links with the best elements of the people in defence of their social and economic interests, no effective discipline or pressure from below to keep the leadership responsive to the needs of the rank and file, and this leadership was in any case drawn in the main from shopkeeper and gombeen elements who were inherently prone to abandon the people they represented once they got the offer of a government job

NEO-COLONALISM - the 1950s and 1960s

When Fianna Fail in the l930s failed to prohibit the free export of Irish capital abroad independent Irish manufacturing capitalism was doomed. For this meant that the bulk of the annual surpluses (of output over input) in the economy was invested abroad through the banks, insurance companies and private holders of large capital. Because of this Twenty Six County industry could not expand its internal market; it was starved of capital, and native Irish industry merely replaced imports. Few industries had sufficient capital to become big and strong enough to enter export markets on any great scale. Home industry, as a result, was frequently feather-bedded and of low efficiency, offering second rate goods to the consumer, including the farmers, who in this way helped to subsidise numbers of the protected industries and enabled their owners to make a profit.

In 1938, under the Anglo-Irish Trade Agreement, Britain had allowed the protection of Irish industry, knowing that these industries would be unable to expand and become internationally competitive on the basis of the Irish home market alone because of the failure to check the export of Irish capital. By 1959 the attempt to develop home industry while allowing the free investment of the economic surplus abroad had worked itself out. It was clear that Twenty-Six County industry could no longer expand on the basis of the home market alone, and indeed it could not provide employment for the huge number of unemployed in the country in 1956 and 1957 and for the numbers of people leaving the land.

One alternative would have been to restrict capital exports; but if Fianna Fail had not dared to do that in its radical days in the 1930s, they were certainly not going to do it twenty years later, when the manufacturing interest it had originally represented had established all sorts of ties and links with commercial, banking and large farm capital which had been its opponent in the days of the Blueshirts. The other alternative was to throw open the doors to imperialism and invite foreign interests in to develop the country in whatever ways they might consider profitable. This was in fact the first step taken, disguised for the people under the title of a "Programme for Economic Expansion".

The Control of Manufacturers Act, requiring a majority of shares in new companies to be in Irish hands, was repealed. Foreign capital was offered tax concessions, grants and the prospect of good supplies of relatively cheap labour to induce it to set up in Ireland. In the period 1958-66 this led to the establishment of some 200 new enterprises in the Twenty-Six Counties and a considerable expansion of industrial employment. Some of this foreign capital led to new production; more of it took the form of take-over bids for Irish industries and distributive units, house property and land. Large sections of independent Irish business were reduced to the position of subsidiaries of British and foreign capital

Increasingly the independent Irish manunfacturers and entrepreneurs of the 1930s became the local managers of British and foreign firms in the 1960s. By 1966 one fifth of the managers and executives of Irish firms were non-Irish nationals, and this astonishing proportion reflects a much greater of capital ownership and control. The independent Irish manufacturing class whose interests Fianna Fail had represented and championed in the late 1930s ans 1940s is gradually being penetrated, taken over and replaced by foreign capital in all major sectors of industry.

This process has already been almost completed in the Six Counties, where the area has remained part of the United Kingdom from the beginning and where there was never a government with protectionist ideas or power to implement them even if it had them. The Twenty Six County Government had that power, won in 1921, but had been week and too bound up with property to push the policy to its logical conclusion. Increasingly, therefore, Twenty Six County capitalism will come to have much the same relation to British imperialism as Six County capitalism - one of utter dependence. The decisions as to what will be produced and where, will lie mainly in British hands, and the character of the Irish economy and the extent of employment will be decided in London rather than in Dublin as was the case in the 19th century.

The state sector of Irish industry, which is the main section not in foreign hands or under major foreign influence could still be used by a government that wished to develop new processes and enterprises; but this would lead to competition with home or imported goods and lead to strong political pressures on the Government, which, as one primarily serving private enterprise, it would not be likely to resist. The likelihood indeed is that the Dublin Government will cease to develop further state enterprises in production and will sell off the private (including foreign) buyers the profitable sections of the state enterprises that already exist; so that foreign capital can purchase a hold on Irish state enterprise as well. This is the logic of the present position at any rate. In the meantime between £400 and £500 million of Irish capital is invested in Britain and abroad by Irish banks, insurance companies and private investors.

These trends reflect a neo-colonial situation in the Twenty-Six Counties of Ireland. Unlike the North, the South is not a direct colony of imperialism, occupied and garrisoned by British troops. The main decisions as to economic policy - and therefore, inevitably, political policy - are made by the British firms which increasingly dominate the economy and whose interests are served by the British Government in the political sphere. Indeed from the point of view of imperialism this method of control has many advantages the direct method had not got. Britain can let Ireland have all the trappings of political sovereignty, a Parliament, a flag, an Irish emblem on our postage stamps; but if the real decisions are made in London the reality of control lies there, and there is no awkward anti-imperialist movement to deal with as there was in the 19th century.

The banker and take-over-bidder are much less palpable enemies to deal with than an occupying soldiery - and much cheaper. Moreover, if the Twenty-Six Counties were part of the United Kingdom again politically, Britain would have the awkward task of trying to placate a large contingent of M.P.s from Ireland in the Westminster Parliament as she had to do in the Union period. As it is, the neo-colony has no representation at Westminster, which makes it much easier for Britain to effectively take the main decisions for the country without having to suffer any adverse consequences.

Indeed this neo-colonialist position has such obvious advantages to the imperial power that there have been signs in recent years that Britain might not be averse to allowing the political reunification of Ireland and the ending of Partition, as long as both parts of the reunited country were economically dependent and there was free movement of labour, capital and goods between the two countries as there was in the Union period. Several British political leaders have put forward such ideas in recent years. Such a development would also save Britain quite substantial sums which she spends in the Six Counties every year and which give a dwindling political return as the Dublin Government moves to oust the Stormont administration as the main favourite of the imperial power.

The success of neo-colonialism in the Twenty-Six Counties following the abandonment by Fianna Fail and the leadership of Twenty-Six County capitalism of the attempt to establish themselves independent of imperialism, is in turn the main reason for the present division in Ulster Unionism. Unionism, led by Captain O’Neill, has been given its instructions by its British masters to make itself more respectable, to brush discrimination, gerrymandering and bigotry under the table, while Britain economically "integrates" the Twenty-Six Counties with the United Kingdom. In this situation the old warcrys and sectarianism of the Orangemen no longer are as useful to Britain as they were in the past; they would impede the development of good relations and integration with the south.

And so the British Government urges the political leaders of North and South to meet and join together. The old fashioned Orangemen have been replaced by the leaders of Fianna Fail as the favoured servants of imperialism. The Orangemen are in fact being sold down the river by the British Government, which always regards Ireland as a whole and wishes to have the whole island in a state of political and economic dependence. Many of the Orangemen do not appreciate that they are politically expendable by imperialism, and the Paisley movement is an attempt to assert the old certitudes of the Unionist faith - anti-catholicism and anti-republicanism - in a situation where they are increasingly less and less useful to the neo-colonial policies of Britain in Ireland.

At present there is free movement of labour and capital between the Twenty-Six Counties and Britain. Following the signing of the Anglo-Irish Free Trade Agreement in January 1966 and its coming into force over a 10 year period, there will be free movement of goods also; and the economic position of the Union period will have been restored in all its essentials. Joint membership of the E.E.C. will also bring certain elements of political union between Ireland and Britain.

The Free Trade Agreement and membership of the E.E.C. represents the final capitulation of Irish capitalism before imperialist pressure. In October 1964 the British government unilaterally broke the terms of the 1938 Trade Agreement with Ireland by imposing a levy on Irish exports to Britain. The Dublin Government’s reaction to this was not to take measures which would reduce Ireland’s dependence on Britain, but to open negotiations for a full economic union. Over a 10 year period the existing tariffs and quotas that still protect the Irish home market against outside competition will be gradually done away with and by 1975 British industry will have a free run of the Irish market as it had during the 19th century and indeed as it had in the main until Fianna Fail began its industrialisation programme in 1932. In return for this Ireland got a few minor concessions for our exports which are not likely to amount in value to more than £5 million a year at least.

The wheel has come full circle. The representatives of what is left of Irish manufacturing capital (Fianna Fail) and of Irish commerce, banking and the big farmers, (Fine Gael) were in favour of the Free Trade Agreement with Britain and our full acceptance of the country’s position as a neo -colony, they were also in favour of membership of the E.E.C. Labour alone opposed both in the Dail, and the republican movement opposed them in the country. The leadership of the national independence struggle which the "men of property" seized in 1919 and 1920, which passed to another group of propertied men in 1932, has passed now to Labour and Republicans.

During the 1950s and early 1960s the Republican movement continually kept before the people the cause of the Republic and the lesson that the main force responsible for the political and social ills of Ireland was British imperialism, which had divided the country, kept part of it in the United Kingdom and maintained Continual political and economic pressure on the other part to ensure the cooperation of its rulers. No other movement kept these basic facts before the people, nor attempted to give leadership on the basis of a strong anti-imperialist programme.

In the middle 195Os the I.R.A. and the republican movement launched an attack on the British occupying troops in the north and maintained this attack for several years. The military forces available, however, were insufficient to attain their object, despite the courage and self-sacrifice of countless brave men. The Six County campaign too was crippled by having to operate to a considerable extent from a base which was insecure and hostile, as the Twenty-Six County Government and police harried republicans in the rear continually and mass arrests and internments of republicans made leadership and organisation extremely difficult.

For a period too, in 1956, there was widespread political support for the Sinn Fein Party as the political arm of the republican movement, and very large numbers of votes were cast in favour of republicans at the polls and a number of republicans were elected to the Dail, although on an abstentionist ticket so that they did not take their seats. These successful candidates were defeated in subsequent elections, however, and in 1962 the I.R.A. called off the campaign in the North and commenced a regroupment of republican forces and a reassessment of the present position of the anti-imperialist struggle in Ireland. The result was the development of the anti-imperialist struggle on a new plane in the late ‘60s - on social and economic issues in the South and on democratic and civil rights issues in the North.

For the first time a revolutionary mass movement was developing and knitting together all the progressive forces. Neither the Dublin or Belfast governments were able to deal with this new situation. The British Imperial plan for Ireland, which seemed to be progressing so well in the early and mid sixties, now looked like falling to pieces. In this situation the old tricks were played again. As in the days of the United Irishmen, Britain decided to smash the mass movement by provoking military confrontation. The Belfast government was used to develop sectarian conflict and thus bring out the guns, and the Dublin Government was used to split the Republican Movement by offering guns and money to the militarists. The Provisionals were born and gradually the initiative passed from the people to the new military elite.

Now the British Government and its Belfast and Dublin puppets were on firm ground again and it was only a matter of time until the Provisionals were isolated and defeated. They had hoped however that the rise of the Provisionals would mean the total eclipse of the Republican Movement and they concentrated all their propaganda on giving the impression that this in fact was happening. They underestimated the strong roots which the Republican Movement had put down amongst the people during the early years of agitationary struggle. This, and only this, has saved the Movement from extinction. Now that the militarism of the British forces and of the Provisionals are self-defeating, the revolutionary movement stands poised and ready to renew the struggle.

The regroupment and reassessment is still continuing. It entails an analysis of the changing strategy and policies of imperialism in Ireland, particularly in so far as it has assumed a neo-colonialist character and has changed its forms of control and domination of Irish destinies. It entails an analysis of the past history of the Irish republican movement in its various phases, with a view to understanding the mistakes and failures which were made in former years and avoiding them in the present and the future.

It entails above all a ruthless realism in assessing the existing situation, avoiding the sentimentality and wishful thinking which has so often led republicans astray in the past shunning any attempts to repeat the battles of the past in a changed environment, and working out the policies and organisational means whereby the movement can attain its object of a united Republic, politically and economically in charge of its own destinies, with an educated, prosperous and contented people, in which the exploitation of man by man has been abolished.

The lessons are:

1. The abandonment by Fianna Fail in 1958 of the attempt to maintain an independent Irish manufacturing class independent of British imperialism. The economic penetration of the Twenty Six County economy by British business. The different aspects of neo-colonialism culminating with the Anglo-Irish Free Trade Agreement and the prospect by 1975 of completely free movement of goods, capital and labour between Ireland and Britain. The increasing unimportance in this situation of a political border within the country, as both parts are economically "integrated" with Britain. Britain’s changing demands on Ulster Unionism as neo-colonialism establishes itself more and more firmly in the Twenty Six Counties.

2. Labour and Republicans as the only forces in the country opposing this process and seeking to give an alternative lead to the people on an anti-imperialist programme of national independence - but the appropriate organisational forms have not been worked out.

3. The failure of the attempt made by the I.R.A. and the Republican Movement in the 1950s to dislodge Britain from the North by means of physical force. The reasons for this being the lack of sufficient military strength and the absence of a government in the south which would support the attempt, or at any rate maintain neutrality. The active hostility of the southern government put the I.R.A. under a crippling disadvantage. The relative success of Sinn Fein at the polls for a period, during the latter 195Os, and the election of a group of abstentionist T.D.s, followed by the failure to maintain this support.

4. The working out during the early and middle 1960s of new policies and organisational methods which would enable the movement to learn from the failures of the past and carry the struggle for independence to a successful conclusion in the circumstances of today.

5. Physical force can be seen as justified in defensive action on behalf of the people but not in offensive action.

BOOK TO READ: I.R.A. Speaks (in the 70s.)

THE LESSONS OF HISTORY:

It should be clear from a study of the history of the Republican Movement (Historical: Part I) that a wide variety of organisational forms have been used by the Irish people to attempt to achieve their national revolution. The recipe for success appears to be composed of various elements, of which the key ones are:

1. The existence of a body of theoretical thought, expressed in writings, capable of making understood to the mass of the people a credible alternative to the current form of rule by the foreigner, and of guiding and educating the most patriotic and politically aware and principled sections of the people.

2. The existence of an organised body of men, prepared to resort to arms if necessary and therefore subject to discipline, who are capable of rousing the consciousness and understanding of the common people towards the achievement of the national objectives, and organising and leading them both locally and nationally.

3. The extent to which the interest and the political and social outlook of the ‘men of no property’ predominate in the national independence movement: historically, it has been shown time and time again that the larger the propertied interests, the more prone they ire to come to terms with foreign rule. The ‘men of no property’ in the present context may be taken to cover all sections of society where functions of creative or productive work predominate over any incidental function of owning property that they happen to have: it therefore includes the wage-worker, the working farmer, the working owner-manager of the small business, as well as the self-employed, the professional, the intellectual and creative worker, etc. Where income from investments starts to predominate over earned income, the point of view of the ‘man of property’ starts to dominate. Thus, it would be narrow and exclusive to interpret Tone’s concept of the ‘men of no property’ as meaning the first category only, as some ultra-leftists have been known to do.

4. The existence of factors which disturb the ability of the imperialists to govern in the manner to which they, had previously been accustomed, and which create a political crisis for imperialism. In the modern world generally the crisis of imperialism in the present century has given tremendous impetus to national liberation movements everywhere. In many ways, the opportunities for Ireland winning genuine national independence are more favourable than they were 50 years ago. An Irish Republic In the seventies would have many friends in the world which did not exist then, especially among the ex-colonial nations which were more successful in getting their freedom than Ireland was.

The absence of any one of these four factors is enough to render a revolutionary movement unsuccessful. At the same time, the presence of all is no guarantee of success: it may happen, as has happened many times, that the enemy may be too powerful, or that chance events or incompetent leadership may do irrevocable harm so that an opportunity is missed.

All four factors existed in the 1798 period. The writings of Tone, the formation of the United Irishmen, substantially based on the landless peasantry, and the English war with France, constituted the four factors listed above. Were it not for the adverse weather conditions preventing the French landing at Bantry Bay in 1796, a successful revolution might have been achieved, the weakness of the national leadership being outweighed by the presence of Tone and the French.

The O’Connell movement failed on all counts. O’Connell’s political ideas went no further than repeal of the Act of Union (with English consent) and the establishment of a local landlord parliament. He had no organisation worth the name, had an instinctive distrust of the radicalism of the people, and English rule was undisturbed by any outside factors.

The famine in the 1840s provided a major disturbing factor. Davis, Lalor and Mitchel had developed republican thought and presented a credible and revolutionary alternative (Lalor‘s demand that the people should eat the grain that was growing in the country during the famine years rather than sell it to pay the rent).

But the organisational spadework had not been done, and these ideas were never explained to or grasped by a sufficiently wide section of the ordinary people, who remained unorganised and apathetic in face of the tremendous disaster of the famine.

The Fenians were strongly organised on a military basis, but lacked mass popular backing based on championing the people’s economic and social needs, so that when they sought to lead the people militarily against England, the mass of the people did not follow. Their writings, or at least those which are readily available, also show little sign of their having thought out a credible alternative form of government. At the time, the impact of the famine was fresh, and it is understandable that pure hatred of foreign political tyranny and military occupation would have been deemed enough to fuel a revolution. The history of the Fenian failure shows the ineffectiveness of the purely conspiratorial approach.

The Land League period was characterised by moderate political thought (Parnellite Home Rule and the New Departure) which might have evolved a more radical character (No man can set the bounds to the march of a nation — the famous Cinncinati speech) and to a good mass-based organisation (the Land League, had it been necessary, would have risen in arms to defend Home Rule). But it occurred at a time when the English were reaping the first fruits of their conquest of Africa, so that she was wealthy enough to buy off sections of support from the Land League by means of a succession of Land Acts, which successfully drew the teeth of the agrarian revolt by helping the tenants to buy the land from the landlords.

The failure of the moderately-led Parnellite movement to absorb the intransigent Fenian element which ultimately developed into the Invincibles was to prove Parnell’s downfall, together with the O’Shea affair which was skillfully used by the English government to divide the Irish, then and for decades after. Parnell, an intelligent and far-sighted landlord could hardly have been expected to develop into a national leader capable of absorbing and maturing the radicalism of the Fenians. In a sense, his inadequacy in the situation was inevitable.

The 1913-23 period was closer to the 1796-98 pattern. A credible alternative had been developed in the writings of Connolly and Pearse, and was widely understood. Mass Organisations existed; the Irish Volunteers, the Transport Union (whose politically most mature sections Connolly was working to develop into a revolutionary force in the Citizen Army) and the First World War was at its height, with imperialism in crisis. The 1916 Rising might well have had a much greater degree of military and political success had the full force of the Volunteers been mobilised. The cardinal error of 1916 of allowing someone ‘not in the know’ (Mac Neill) to be nominally in the leadership, with all the adverse consequences of this, must be attributed to the Fenian conspiratorial tradition. Moreover, it might be said that the rapid growth of trade unions and co-operatives in Ireland during the 1900s was not widely enough seen - by the IRB leaders in particular, as of national revolutionary potential, although the Black and Tans recognised this well enough when they later burned trade union offices and co-operative creameries on a huge scale.

As well, even if the 1916-21 struggle had succeeded militarily against the English, it would still have left a million Orangemen to deal with. After 1919, the national movement in the North had been left almost entirely in the hands of Devlin and the Hibernians. No serious attempt was made by the leaders of the post-1917 Sinn Fein to win the Protestants of the North to the side of the Republic, even though the real interests of many of them could never be served by retention of the union with England - though they might not easily see this themselves because of their sectarian delusions.

The Civil War period and the 1920s showed little or no evidence of theoretical thought, the necessary social objectives of the national revolution having received no attention since Connolly. The anti-Treaty I.R.A. failed to identify themselves with the economic and social needs of the people, as Mellowes had proposed, and the trade union and Labour movement remained organisationally neutral in the Civil War under the leadership of timid officials, thus enabling the Free State to bring its full military weight to bear on the I.R.A., with the assistance of Britain.

The thirties and forties again showed a failure to link the military struggle for the Republic with the political and economic struggles of the people. By and large, the impossible was attempted under adverse conditions and without well worked out and credible alternatives.

The fifties broke new ground with the appeal by the Army Council to the Ulster protestants to support the independence movement, but a viable link-up with the mass-organisations of the people was not achieved, and the resources were not available to expel Britain militarily from the North. Moreover, one of the basic requirements of guerrilla warfare was missing, namely the ability to move among all sections of the common people as a fish in water. Also, it was not possible to establish a continuous liberated area to act as a safe base.

In the sixties, a credible alternative to imperialist domination began to emerge with a widening appreciation of the character of neo-colonialism in Ireland, and as the pro- imperialist and basically unionist nature of the leadership of the Fianna Fail and Fine Gael parties in the 26 Counties was more and more clearly seen. The inability of Irish big business to lead the national revolution to success has been demonstrated to all those with eyes to see. Successive sections of Irish business - commercial and big farming capital under Cumann na nGael in the twenties; Irish manufacturing capital under Fianna Fail in the thirties and forties - have done a deal with imperialism at the expense of the mass of the people.

Native Irish capital has proved too weak and too compromising to lead the nation to full independence. Indeed, the last fifteen years have seen large Irish capital increasingly absorbed and taken over by British and foreign capital. The main firms in Ireland now, with the exception of the State companies, are foreign owned or have major foreign shareholdings and ties. Their interests have become identical with those of their parent companies in Britain. The signing of the Anglo-Irish free trade agreement and the 26-County government’s entry to the EEC marks the complete capitulation of native Irish capital before imperialism.

There remains the mass of the people whose are still unalterably opposed to imperialism and aligned with the movement for national independence. These are the workers and small farmers and those sections of small business and the intellectuals who are adversely affected by the domination of British and foreign capital in Ireland. Numerically, they make up the bulk of the people, although they are disunited, divided into many different organisations and parties, and widely unaware of the country’s problems and the real cause of them.

There now exists the framework of a national organisation with the necessary understanding of the character of modern imperialism and the nature of the anti-imperialist forces in the country. A programme has been evolved which reflects the anti-imperialist interests of the mass of the people, and which links the demands of workers, small farmers, intellectuals, and small business people, with anti-imperialism, with the movement for political and economic independence and for the Republic.

Appropriate forms of organisations of the national movement to carry the independence struggle to a successful conclusion during the coming period are being worked out, and the Movement is conscious of the vital importance of relying on and expressing the demands of the men of no property, if theoretical clarity is to be maintained, if policy-making is to be principled and intelligent, and if the leadership of the Movement is to rest in the hands of men who will not compromise with imperialism under pressure because of the nature of their personal economic interests. It is appreciated also that it is of vital importance to establish and maintain indissoluble links between the political/military and social/ economic wings of the Movement to prevent the struggle becoming compartmentalised, as has so often happened in the past, this being a sure guarantee of failure.

The imperialist power is in a situation of deep crisis at the present time, finding it increasingly difficult to maintain the huge profits it has been drawing from the neo-colonial exploitation of its former empire, and coming more and more under the political and economic influence of the United States. Britain is entering the Common Market to get the assistance of the European powers to meet the expenses of colonial exploitation (the ‘east of Suez’ policy) and to use European competition to cut the wages and incomes of the mass of the British people to make possible greater profit for the big monopolies.

Britain is increasingly unable to stand on her own as an imperial power. In this situation Britain will be increasingly anxious to weld Ireland more tightly to her side as a secure neo-colony, while the opportunity for Ireland to take advantage of Britain’s weakness and isolation and to strike out on an independent political and economic course becomes greater. The anti-imperialist movement, the movement for the liberation of nations which Ireland inaugurated in 1916, is a powerful force in the world today, and an Ireland that embarked on a radical national independence policy could count on mighty friends which did not exist 60 years ago.

The coming period should therefore see a new stage in the national independence struggle, one in which the lessons of the past will have been studied and learned and which will carry the independence struggle to a successful conclusion by establishing in Ireland, a united, democratic Republic, politically and economically independent, and governed for the benefit of the People.

WHAT YOU CAN DO

TO ACHIEVE FULL ECONOMIC AND

POLITICAL FREEDOM FOR THE IRISH PEOPLE

Join the

Republican Movement

We STAND for the OVERTHROW of British Imperial Rule in Ireland.

We STAND for an INDEPENDENT IRISH SOCIALIST REPUBLIC.

We OPPOSE all FOREIGN financiers, speculators, monopolists, landlords, and their native collaborators.

We PLACE the RIGHTS of the common man before the right of property.

We CLAIM the OWNERSHIP of the wealth of Ireland for the people of Ireland.

Unite to Fight!

Call or write to:

The Secretary,

Sinn Fein,

30 Gardiner Place,

Dublin 1. 41045-40716.

|