Extract from 'The Politics of Force: Conflict Management and State Violence in Northern Ireland' by Fionnuala Ní Aoláin (2000)[Key_Events] [KEY_ISSUES] [Conflict_Background] VIOLENCE: [Menu] [Reading] [Summary] [Background] [Chronology] [Incidents] [Deaths] [Main_Pages] [Statistics] [Sources] The following extract has been contributed by the author Fionnuala Ní Aoláin , with the permission of Blackstaff Press. The views expressed in this extract do not necessarily reflect the views of the members of the CAIN Project. The CAIN Project would welcome other material which meets our guidelines for contributions.  The following extract is taken from the book:

The following extract is taken from the book:

THE POLITICS OF FORCE

Front cover photograph: Hooker Street, Belfast, 1969

Orders to local bookshops or:

The following extract is copyright Fionnuala Ní Aoláin (2000) and is included

on the CAIN site by permission of the author and the publisher. You may not edit, adapt,

or redistribute changed versions of this for other than your personal use

without the express written permission of the author or the publisher, Blackstaff Press. Redistribution for commercial purposes is not permitted.

From the back cover:

This book starts from the premise that everyone has a right to Life and questions whether all those killed at the hands of the security forces needed to die. The conclusion is that they did not.

The use of lethal force by agents of the state between 1969 and 1994 in incidents like Bloody Sunday and the Gibraltar shootings has engendered profound public disquiet in Northern Ireland and indeed throughout the world. Much has been said and written about these controversial deaths, but until now there has been no comprehensive scrutiny of the use of lethal force in Northern Ireland. This important new study fills that gap. Analysing the evidence gathered from her unprecedentedly rigorous research, Fionnuala Ní Aoláin clearly demonstrates that lethal force in Northern Ireland is not an isolated aspect of state practice to be explained away as spur-of-the-moment decisions by lawenforcers. It is an integral part of the states evolving policy of conflict management, along with emergency legislation and the use of legal process. The result is a unique mirror on Northern Irelands legal limbo and on how the state has attempted to manage a protracted emergency within the sometimes constricting framework of a democratic society. FIONNUALA NÍ AOLÁIN, a former Fulbright Scholar at Harvard Law School, was awarded a Ph.D. by Queens University Belfast in 1997. Formerly Assistant Professor of Law at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, she is now Professor of Law at the University of Ulster.

Extract from '1 A brief historical overview' pp 57-71

On 27 October 1980 seven republican prisoners in the Maze prison began a hunger strike in protest at the removal of political status. This hunger strike was the culmination of earlier protests, which first began in 1976: from the point at which special category status was denied to republican and loyalist prisoners, the former refused en masse to comply with prison rules. The most compelling example of this was the dirty protest, so named from the refusal of prisoners to wear prison uniforms, resulting in their confinement to cells and the practical consequences of refusing to avail of the inadequate toilet facilities within those cells.95 It has also generally been overlooked that a minority of loyalist prisoners participated in the so-called blanket protest. This minority was largely unsupported, morally or practically, by other loyalist prisoners and external organisations.96 The hunger strike was abandoned on 18 December 1980, after it appeared that the government was committed to concessions and dialogue with the prisoners. Intentional food deprivation recommenced in March 1981 following the failure of that dialogue. The response of the nationalist community to the perceived inflexibility of the United Kingdom government during the seven-month protest, in which 10 hunger-strikers (7 PIRA, 3 INLA) died, created a political watershed in Northern Ireland. This political metamorphosis goes some way to explaining the change in direction for conflict management in the jurisdiction in the 1 980s. The hunger strikes produced grassroots support for republicanism which was both unexpected and threatening for the state. The election of Bobby Sands, the first hunger-striker to die, to the Westminster parliament was followed by considerable electoral success for Sinn Féin in successive local government and general elections. By June 1983 Sinn Féin had obtained 13.4 per cent of the electoral vote in Northern Ireland.97 Quantifying the effect of the hunger strikes on security policy is not straightforward. The subsequent high electoral support for Sinn Féin compounded the view in certain governmental quarters that there was a hard-line element in the nationalist community, actively supportive of the politics of violence. The tactics of negotiation would not reposition this hard-line constituency in relation to their views on the internal political structures of the United Kingdom. Sinn Féin support was read as a failure of the policy of normalisation, because it illustrated that the policy had floundered among a considerable segment of the nationalist population. In military terms, a simplistic read would see votes for Sinn Féin as a network of support for an ongoing campaign of violence. Practically translated, that meant safe houses, a flow of information about the state and its agents, and an unwillingness to lend support to the forces of law and order. With this analysis in hand, a more systematic return to active counterinsurgency was predictable. What the dissection failed to recognise was that the high point of support following the hunger strikes was intimately linked to what one commentator describes as a tribal voice of martyrdom, deeply embedded in Gaelic, Catholic, Nationalist tradition.98 The point being, that initial electoral success by republicans can be linked to emotive responses evoked by the historical analogies of martyrdom, as opposed to direct and unequivocal support for political violence. A While the hunger strikes laid bare a grim moment of political consciousness misunderstood by the state, the stage for what followed had, in fact, been set much earlier. By the late 1970s the state had come to realise that the policy of normalisation was not producing the intended long-term results for conflict containment. The hunger strikes merely confirmed this political fact. When police primacy became a pivotal political reality, the seeds were sown for active engagement against those violently opposing the state. By the end of the 1970s the RUC was emerging as a self-confident, modern police force. When Kenneth Newman was Chief Constable, strong emphasis was placed on modernising the force and integrating the RUC into mainland police structures and practices, while maintaining a parallel militaristic and civilian role. The militaristic function was evidenced by its sophisticated weaponry, the centralisation of intelligence and its role in processing detainees under the emergency legislation. Its rising political importance, allied with internal beliefs about its military capacity, created the assumption that the police were capable of taking on active counter-insurgency within the jurisdiction. Thus, the evolution of the RUC is crucial to conceptualising the re-emergence of a policy of active counter-insurgency, and its reformulation when police control proved to be an utter failure. The police gateway to active counter-insurgency found its inception in the centralisation of intelligence in the RUC Special Branch from 1977 onwards. Traditional hostility between the police and army over intelligence sources was temporarily abandoned, with the creation of integrated intelligence centres called Tasking and Co-ordination groups. The first was created in 1978 and was based at Castlereagh in Belfast. Increased RUC control over intelligence sources led to the development of further specialised units within the police apparatus. The year 1980 saw the conception of Divisional Mobile Support Units (DMSUs), specialised units trained in militaristic responses to riot and crowd-control situations. These were intended to provide flash-point support when the ordinary police were unable to cope. Incrementally the policy of specialisation was pursued within the RUC, This involved creating Headquarters Mobile Support Units (HMSUs), specialist units to support ordinary police in rural areas. Finally, spearheading the developing hierarchy were the Special Support Units (SSUs). All these units were sustained by informer information, which was, in turn, facilitated by extended detention powers, and remained the main-stay of the police response to terrorism. The SSUs were to become especially important. They were SAS-trained, with an emphasis on firearms training and reactive responses to situations of threat. The next logical step, from a police point of view, was to activate the use of these units to specifically combat the paramilitary activity ever present in Northern Ireland. This view was given political credibility by the unfolding events in Northern Ireland in the early 1980s.

B In 1982 the police dabbled directly and ineptly in overt counter-insurgency. Between 11 November and 12 December six individuals were fatally injured by RUC MSUs in County Armagh. Five of the dead were members of republican paramilitary organisations, the sixth was a civilian. All six deaths occurred in controversial circumstances. Two weeks prior to the first deaths, those of PIRA members Gervaise McKerr, Sean Bums and Eugene Toman, three police officers were killed when a large bomb blew apart the car in which they were travelling in Kinnego, County Armagh. Linking these two incidents is problematic. Nonetheless, commentators have suggested that the three deceased PIRA men were linked to a PIRA active service unit that had set up the Kinnego incident.99 The fatal confrontation was preplanned on the basis of informer information, the three men having been under constant surveillance for a considerable time before their deaths.100 They were unarmed when killed and an approximate total of 109 bullets were discharged into their vehicle. In 1984 three policemen were subsequently charged with and acquitted of the murder of Eugene Toman.101 Two other incidents were also characterised by excessive use of force. On 24 November seventeen-year-old Michael Tighe was shot as he entered a hayshed which was under surveillance by an MSU. On 12 December Seamus Grew and Roddy Carroll, both members of the INLA, were shot in a confrontation with undercover police shortly after crossing the border from the Irish Republic. Both were unarmed at the time of the incident. Constable John Robinson was charged with and acquitted of the murder of Seamus Grew.102 These incidents provoked local and international condemnation. A series of inquiries into the deaths failed to dampen nationalist fears that a shoot-to-kill policy was being operated against republican paramilitaries. The most notable was the Stalker inquiry, started by Deputy Chief Constable John Stalker of the Greater Manchester police on 24 May 1984. The police foray into military confrontation had backfired, confirming the armys evaluation that they were inherently unsuitable to the task of counter-insurgency. The political calculation was quickly made. In short, active counter-insurgency by a theoretically civilian police force would always be subject to greater public scrutiny than any similar action on the part of the army and should be avoided. Compounding the failure of the RUC to successfully assume a counter-insurgency role was the collapse of the supergrass system to obtain convictions for terrorist offences. The dubious practice of supergrass trials came into use after the ending of the hunger strikes.103 The process was heavily backed by the police, who provided the raw material to make it work. The trials resulted from informers turning Queens evidence against former alleged accomplices. Their willingness to give such evidence occurred within the confines of protective police custody, and was additionally safeguarded by a system of plea bargaining to protect themselves from punitive criminal sanction. The trials were discredited by the fact that in numerous cases accomplice evidence was uncorroborated, the element of inducement undermined the voluntary nature of the evidence, and the reliability of the witnesses was open to serious doubt. Supergrass operations amounted to a more sophisticated form of internment, as those charged with offences on the strength of supergrass evidence were held on remand for up to two years before trial. The conviction rate was initially high - by the autumn of 1983 three major supergrass trials had resulted in the conviction of 56 of the 64 defendants (88 per cent), with 31 of these convictions (55 per cent) resting solely on the supergrasses uncorroborated testimony.104 On appeal, however, the bulk of the convictions were overturned. The Court of Appeal has nonetheless repeatedly denied that the procedures and rules of evidence applied in the "supergrass" trials failed to guarantee the basic right to a fair trial.105 In the final analysis it seems that the judiciary were unwilling to sustain convictions based on flawed and largely uncorroborated sources. Their willingness to be independent of political pressures was the most significant factor in the collapse of the supergrass system.106

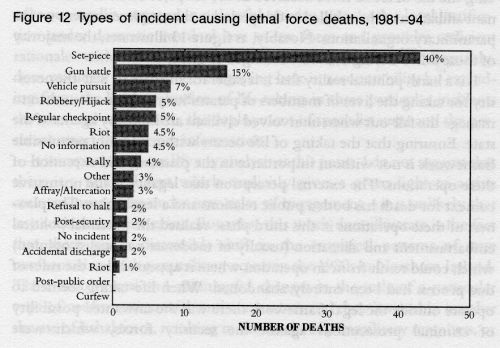

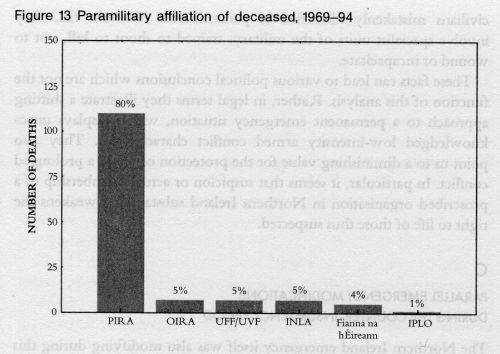

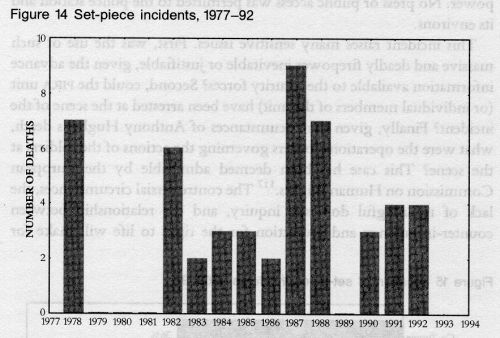

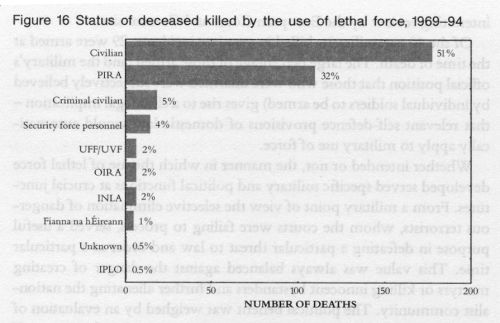

The abandonment of the supergrass trials, combined with the removal of the military option for the RUC, shifted the counter-insurgency balance back in favour of the army. From 1983 onwards the politics of confrontation were largely in the domain of the specialist army units, primarily the SAS.107 The RUC was relegated to the function of providing backup to such operations and providing the informer information that allowed preplanning for military set-piece operations. The resounding political message was that police primacy did not extend to mounting counter-insurgency operations against PIRA. I use the term set-piece to describe the particular kind of specialist operations leading to the use of deadly force which emerged in the third phase of the conflict. The features of these set-piece operations give a grim indication of a discernible shift in state policy as regards the use of force in the 1980s. First, the deployment of specialist units meant that when force was exercised, the soldiers shot to kill. In many preplanned military confrontations the evidence suggests that arrest in the context of these operations did not constitute taking the suspect into custody; it meant eliminating a threat, even if that meant killing the suspect. The decision not to seek custody seems invariably linked with the status of the deceased. Between 1981 and 1994, 40 per cent of all incidents involving the use of lethal force occurred in the set-piece context. The dominant affiliation of those killed in this period in the set-piece context was to paramilitary organisations. Notably, as figure 13 illustrates, the majority of those killed during 1969-94 belonged to PIRA. It is a harsh political reality that it is easier for the state to sell the necessity for taking the lives of members of paramilitary organisations than to manage the fall-out when uninvolved civilians are killed by agents of the state. Ensuring that the taking of life occurs within a legally permissible framework is not without importance in the planning and execution of these operations. The external perception that legality is the normative context for death has both a public relations and a legal value. The planners of these operations in this third phase realised the potential political embarrassment and alienation (usually of moderate nationalist opinion) which could result from an operation where it appeared that the rules of due process had been entirely abandoned. When life-taking seemed to operate outside the legal framework there was the unwanted possibility of criminal prosecutions against the security forces, which were undesirable for two reasons. First, the careers of individual soldiers who were simply following orders were placed at risk. Second, sources of military intelligence might be compromised.

The fact that the suspected paramilitaries were armed and were, allegedly or actually, engaged in unlawful activity gives both a legal justification under domestic criminal law to use force and provides sufficient rationale within the armys own internal guidelines.108 Arguably, domestic legal standards leave a gaping hole in accountability by excluding from the legal evaluation of life-taking in these particular incidents the maximal use of force, the deployment of specialist units and the persistent resort to informer information. It is important to qualify my analysis at this point. I do not suggest that there is a political text which explicitly gives a green light to active counter-insurgency under new rules of engagement - it is unlikely that any such document exists. But what this work does illustrate is the fact that there was a discernible shift in the empirical patterns of state confrontation with paramilitary actors in the 1980s in Northern Ireland. These involve real and meaningful changes in the scale of a particular type of confrontation with anti-state actors and they invariably involve the use of lethal force, resulting in the deaths of paramilitary members, or civilians mistakenly identified as paramilitaries. Without fail, they involve specialist units of the military, trained to shoot to kill, not to wound or incapacitate. These facts can lead to various political conclusions which are not the function of this analysis. Rather, in legal terms they illustrate a shifting approach to a permanent emergency situation, which displays unacknowledged low-intensity armed conflict characteristics. They also point us to a diminishing value for the protection of life in a prolonged conflict. In particular, it seems that suspicion or actual membership of a proscribed organisation in Northern Ireland substantially weakens the right to life of those thus suspected. C The Northern Ireland emergency itself was also modifying during this third stage of conflict management. The most cogent feature of this period was the trend to completely normalise the emergency by transferring emergency powers into the ordinary law in order to cope with civil strife.109 Thus, the invisible barrier between the ordinary and the extraordinary was in a process of being entirely swept away by the state. The prime example of this is the abrogation of the right to silence, first enacted in Northern Ireland in November 1988, now extended to the rest of the United Kingdom. While not a part of the emergency regime per se, its introduction was premised on the perceived difficulty in processing paramilitary defendants in the criminal justice system and allied to expansive predetention powers. The removal of the right to silence was a clear extension of the emergency regime into the ordinary criminal law. Following the 1994 cease-fires in Northern Ireland, Secretary of State Sir Patrick Mayhew announced a powerful, authoritative and independent review of anti-terrorism laws.110 This most recent review of emergency legislation, submitted by Lord Lloyd and Mr Justice Kerr, recommends the imposition of permanent counter-terrorist (emergency) legislation upon the normal legal framework as part of the ordinary law.111 The outcome of the review process illustrates the extent to which the normalisation process has advanced. The basis for their conclusion rests largely on two propositions. First, that terrorism presents an exceptionally serious threat to society. Second, that terrorists have proven particularly difficult to apprehend without recourse to special offence schedules and additional police powers.112 The report sets out five distinguishing features of terrorism, and concludes that their particular characteristics justify the creation of special legislation.113 There is no broad engagement in this review with the historical, social and political context in which the use of emergency laws was developed and refined in Northern Ireland. Parallel to this is a myopic assessment of the threat facing the United Kingdom from terrorism and an unwillingness to intellectually engage with the potential of the ordinary legal system to cope with changed circumstances. The Lloyd review indicates how the use of emergency powers for extensive periods has a distinctive effect on the establishment, which comes to rely upon it legally and politically. The normalisation of emergencies not only creates profound legal trenches but has a discernible effect on the mindset of those who operate within them, and who come to view legal structures through the prism of the abnormal. A practical illustration of this phenomenon in Northern Ireland was the complete retention of the emergency framework throughout the entire period of the ceasefires and beyond. This is generally indicative of how difficult it becomes to dislodge crisis powers once they have become institutionalised within the state. No emergency review has been couched in terms of a commitment to dismantling thirty years of permanent emergency. This is illustrative of the complete ease with which the exception has become the norm in Northern Ireland, and the danger that the exception will become the norm in the United Kingdom as a whole. The long-term use of emergency powers becomes a convenient basis upon which to usurp the protections that all citizens are entitled to under the treaty protections of the European Convention on Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. When a state creates a permanent piece of anti-terrorist legislation, drawn and modelled on pre-existing emergency structures, what we are witnessing is a slippage of emergency laws into ordinary law. This legal act is no less the creation of a permanent emergency than doing so by passing an act of parliament which has the word emergency in its official title. It is also indicative of how the emergency phenomenon evolved once again during 1981-94, where the exception has, in fact, become entirely normalised. The first step towards internalisation of the legally exceptional is the willingness to intellectually rationalise the process of normalising the abnormal. In relation to the right to silence, the localisation of the initial legal changes to Northern Ireland, couched in the language of the exception, lulled many observers in the United Kingdom into assuming that its effects would always remain local to an aberrant situation. In this context, the Lloyd recommendations are not as surprising as one might think. They fit a neat paradigm that localisation is not a feature of governmental practice in relation to the use of crisis powers. Complete normalisation of emergency powers ultimately requires that those facets of emergency authority which identifiably demonstrate difference be made ordinary. This has the effect of limiting the heightened scrutiny of law. Its most worrying aspect is that it actually changes the terms of the discussion itself. That is to say, the process of normalisation changes the debate about the emergency by seeking to redefine the emergency as a normal facet of everyday life. The Lloyd Report is key to this evolving approach in the United Kingdom, as emergency is redefined as an inevitable, if not banal, feature of modem social existence. D The preplanned confrontations in the counter-insurgency phase are more sophisticated than their 1978 forerunners. An example is the Loughgall incident in which eight members of a PIRA active service unit and an innocent civilian were killed by an SAS unit while attacking a small police station in County Armagh in 1987. The PIRA unit was heavily armed and information is limited about the precise details of the incident. On 8 May 1987 a PIRA active service unit attacked the village RUC station with a large construction site digger loaded with 200 lbs of explosives. However, the unit had been under heavy surveillance by the security forces and it is likely that the military had informer information giving advance notice of PIRAs intentions and its specific target.114 Though never officially confirmed, commentators agree that members of the SAS were involved in the specialist unit monitoring and actively participating in the Loughgall operation. With meticulous planning, the SAS went into position within and around the police barracks many hours before the attack took place. Mark Urban has argued that the positioning of the troops inside the barracks was crucial for legal purposes - the military was thus provided with a clear self-defence justification by virtue of the explicit threat posed by the PIRA unit.115 This remains the case notwithstanding the fact that the military were aware of the precise nature of the threat before it was deployed to respond to it. Troops were also placed at key locations within and around the village to prevent the escape of any PIRA members.

The exact sequence of events precipitated by the arrival of the PIRA unit in the digger and a blue Toyota van is unclear. When they got to the station gunfire commenced almost immediately and the bulk of the shooting seems to have come from the SAS.116 The bomb detonated, blowing up the digger and flattening a major portion of the station and nearby buildings. The expenditure of firepower was massive, killing eight PIRA men as well as fatally injuring Anthony Hughes, an uninvolved civilian. The death of this civilian raises serious questions about the manner in which the military operation was conducted. Hughes and his brother Oliver were driving through Loughgall, and upon hearing the massive explosion, they sought to reverse their vehicle and move away as quickly as possible. Soldiers in the vicinity opened fire on the car; Anthony was killed, but Oliver survived, despite being hit at least four times. There is no doubt that the SAS opened fire without warning and without seeking to ascertain who was in the vehicle; and there was no attempt to disable the vehicle or to use minimum, rather than maximum, use of force. The SAS also fired on another car driven by a woman, with her young daughter in the passenger seat. Both escaped serious injury. Immediately after the shootings the area was totally sealed off by armed police - a clear indication that the police operated in a mop-up function to the military power. No press or public access was permitted to the police station and its environs. This incident raises many sensitive issues. First, was the use of such massive and deadly firepower inevitable or justifiable, given the advance information available to the security forces? Second, could the PIRA unit (or individual members of the unit) have been arrested at the scene of the incident? Finally, given the circumstances of Anthony Hughess death, what were the operational orders governing the actions of the soldiers at the scene? This case has been deemed admissible by the European Commission on Human Rights.117 The controversial circumstances, the lack of meaningful domestic inquiry, and the relationship between counter-insurgency and protection for the right to life will make for interesting review by the European Court and Commission.

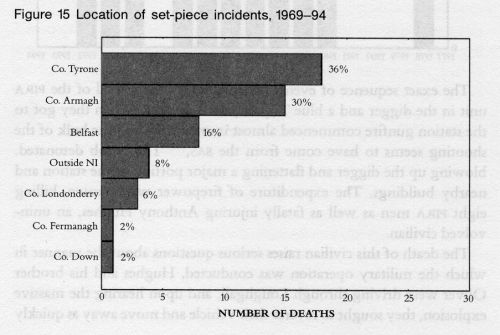

Of the 40 paramilitaries killed in set-piece incidents, 29 were armed at the time of death. The large percentage of those armed (and the militarys official position that those who were unarmed were subjectively believed by individual soldiers to be armed) gives rise to a clear legal implication - that relevant self-defence provisions of domestic law would automatically apply to military use of force. Whether intended or not, the manner in which the use of lethal force developed served specific military and political functions at crucial junctures. From a military point of view the selective elimination of dangerous terrorists, whom the courts were failing to process, served a useful purpose in defeating a particular threat to law and order at a particular time. This value was always balanced against the danger of creating martyrs or killing innocent bystanders and further alienating the nationalist community. The political benefit was weighed by an evaluation of that alienation and how it would affect mainstream political processes. If one were to take the extreme view that the hunger strikes had revealed a nonparticipatory and disaffected nationalist community who were not worth wooing politically, then the benefits outweighed costs. It is interesting to note that these deaths are predominantly confined to specific geographical areas. On one reading, we can surmise that these areas are so republican that the effect of lethal force killing does little more than confirm local opinion on the partisan nature of the security forces. The dangers for the body politic in Northern Ireland only came when such incidents affected moderate opinion about the security forces and the control exercised over them by the state. It is also interesting to note that the use of force has been significantly used less frequently against loyalist paramilitaries in comparison with their republican counterparts (see figure 16, p. 70). This can be explained on a number of levels. First, if one accepts the thesis that lethal force performs a political function for the state in controlling insurgency, it is obvious for historical reasons that a loyal Protestant community would not be considered a threat to the secure status quo. Thus, there exists no political rationale to use force as a mechanism of control against that community. Second, in the class of lethal force deaths caused by the police or local part-time military forces, such as the B Specials or UDR, there is some validity to the assumption that the overwhelmingly Protestant make-up of these bodies would make it less likely, for psychological and social reasons, for their arms to be exercised against their own communities.

In the early part of the conflict the security forces were not made the object of attack by the majority community. There has been a minor shift in this pattern following the signing of the Anglo-Irish Agreement in 1985, with the emerging loyalist view that the security forces were the cutting-edge of its enforcement.118 In a divided society where conflict becomes normalised, an army working in aid of the civilian power finds itself communally and individually required to identify hostile elements. Thus, the pitting of identified segments of the nationalist community against the state (real or imagined) also becomes a road map for the military in its relationship with that community. That road map becomes part of the unstated background in which lethal force is exercised. VI The use of lethal force represents an exercise in control and legitimacy. In the normal course of events in a healthy and functioning civil society lethal force is an aberration for the state. Against such a background, the protection of citizens right to life lives up to its cherished rhetorical position - the taking of life is sanctioned only by justificatory or excuse rationale established by constitutional or criminal law.119 In the entrenched emergency context of Northern Ireland, the taking of life became a systematic response exercised with political flexibility, and constituted an alternative mechanism to control aspects of the internal crisis facing the state. Modifications to the criminal justice system and attendant procedures, restrictions on freedom of expression for the press, draconian powers of stop and search, militarisation of certain communities on a par with martial law, all failed to stem the continuing violence. The essentially political nature of that violence was virtually unaddressed by a lack of political dialogue and agreement. As a result, the state operated on a variety of levels to control civil disorder - the strategic exercise of force by its agents was merely one choice on that continuum of control.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||