'Hard News', in, Eyewitness: Four Decades of Northern Life,

|

| There was nowhere to go. I tried to get comfortable, taking a couple of pictures out of bravado. I kept my head down, and time to reflect on the words of Cyril Cain, one of the classiest photographers in Belfast. 'Only Houdini catches bullets in his teeth,' he had said. |

CHAPTER 6: 'HARD NEWS'

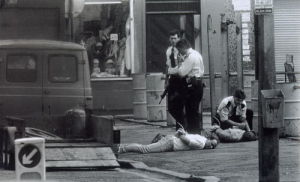

I walked into Divis Flats, but I crawled out on my belly. Bullets lifted chunks out of the ground around me and pinged off the balconies. I got one mediocre picture.

It was 1975. I was in the Daily Mirror office when we got a call that there was shooting in Divis. I knew the area well. My bar had been flattened to make way for the flats. Some streets were still standing, and I knew how to navigate my way without venturing on to the main Falls Road. I left my car and walked towards the flats — hexagonal slums-to-be, surrounding a rectangular block that towered over everything. There was some shooting, but it was far off, from the direction of Ballymurphy.

The balconies were quiet. Someone recognised me and warned me to be careful, explaining that an initial encounter between the IRA and loyalists on the other side of the peaceline had turned into a three-way gun battle involving the army. I was pointed to one balcony where, I was told, a man had been shot.

I climbed a stairwell to discover a wounded man being bandaged. He had been hit in the arm. As I lifted the camera to take a picture, a woman shouted, 'Get that f***ing photographer out of here.' Suddenly those who had been tending to the wounded man seemed to want to tend to me. I didn't have time to marvel at the fickle nature of the crowd — one day it would be, 'Show the world what's happening here,' and the next, 'Yer man's trying to take a photograph, get him.' I got a couple of frames. As I was jostled, there was a burst of gunfire. We could hear the 'thunk' of the bullets hitting, somewhere close overhead. Everyone went flat.

Bizarrely grateful for the distraction, I retreated down the stairwell. At the bottom I stopped. I had a choice — I was pretty sure I had a picture of a wounded man. It wasn't great by any means, but would keep the picture desk happy. If I stayed put, there was no way of telling how long it would take to get out. On the other hand, a quick run across some open ground to neighbouring streets would get me back to the car. From there, I knew a route I could drive that would not expose me to any real danger. There was a lull. It seemed worth the risk.

Neither quite walking nor quite running, moving half crouched, I began my bid for safety. I could not have been more wrong. 'Wham, thunk! Wham, thunk! Wham, thunk!' in quick succession. In the fraction of a second between each round it was as if my brain raced faster than a motor drive. 'Wham, thunk!' I couldn't see a thing. 'Wham, thunk!' They were close. 'Wham, thunk!' At least I could hear the shots — I'd always been told you wouldn't hear the shot that killed you.

I dived behind a huge stone bollard that had been placed to prevent car bombs being driven into the area. In my mind it was a cat-like movement, reminiscent of one of my silver-screen idols. 'Keep down, you eedjit,' someone shouted from the cover of another stairwell. 'They're on top of the mill.' It was sage advice. Andrews Flour Mill overlooked Albert Street and the area around St. Peter's Pro Cathedral. Many of its workers once drank in my bar. Now, it seemed, someone was using it as a sniping position. A sub-machine gun chattered back nearby.

For the next two hours I stayed behind the rock, getting to know well its every grain and contour. I promised God if He'd just get me out of this one I'd live a good life. Bullets kicked up the ground around me. By the sounds of the various guns, I slowly identified positions from where I thought people might be firing. The sub-machine gun owner seemed to be at the corner of a street just beyond my view. Every so often he'd make a contribution. At least four, possibly more, riflemen were moving about on the ground and on the balconies. Those weapons had a hell of a roar. Every so often there was the crack or pop of pistols.

There was nowhere to go. I tried to get comfortable, taking a couple of pictures out of bravado. I kept my head down; and had time to reflect on the words of Cyril Cain, one of the classiest photographers in Belfast. 'Only Houdini catches bullets in his teeth,' he had said.

Eventually, during a lull, I made a move, crawling quickly across the waste ground. As I reached its edge there was another machine gun burst nearby. I got up and ran to the cover of a wall, the ground sucking up every step as the soldiers this time returned fire. Was it my imagination or did the earth shake? I don't know how close any of those bullets came. I don't want to know.

It took me four hours to get back to the office. 'Where have you been?' was the first question when I walked through the door. 'What have you got?' was the second. I waited for the roll to be developed. There was one badly composed picture of the man being bandaged. It made the front pages — there must not have been much else going on. Also on the roll were a couple of low-level shots of the patch of waste ground. I took the pictures because, when my life seemed dependent on the thickness of a rock, I had wanted to record the moment. To call those few frames nondescript would have been generous. A staffer eyed me curiously. 'Not much in that then,' was his verdict.

He was right. To anyone but me those pictures meant nothing. Provisional and Official IRA members, I found out later, had jointly taken part in one of the biggest gun battles for many years in the city. I was scared, but I learnt an important lesson that day about hard news: Covering a gun battle with a stills camera is like fishing for shark with a safety pin. Wounded people make hard news pictures. That's an unfortunate fact. The actual moment of them getting wounded in a gun battle, however, more often than not looks like damn all to a stills photographer.

A television cameraman, in Divis that day, won an award for his coverage. The sound of the shooting was vivid and sharp, and there was drama in every jerky movement. It's rare that a picture of people being shot or shooting makes a powerful still image. The people who take those photos are rarer still. They are hard news photographers of unique genius, courage and quality.

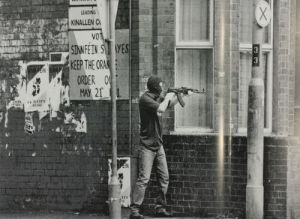

I am a press photographer and in my twenty-five or more years only once have I taken a picture of someone firing a gun in anger. The context? Within days an Orange march was due to pass along the Ormeau Road in south Belfast past nationalist streets. In previous years, to allow the marches to go by, a large number of police prevented residents leaving those streets. On one notorious occasion those taking part in a parade gestured as they passed a betting shop where loyalists had killed five Catholics from the district. This time, a few days ahead of the proposed parade, objectors organised a protest rally. Tension in the area was palpable. Reporters, cameramen and photographers were there to cover the protest. They stood around in small groups speculating among themselves and sounding out locals.

I chatted with a reporter. Behind her, across the road, something attracted my attention. I noticed a man walk from an entry and saunter towards the corner. But it was neither his gait nor the fact even he was masked that drew my attention so much as the rifle carried by his side.

For a moment you think this isn't happening, that it's a game. Then everything happens at once. Time accelerates in strange slow motion. The man raised the rifle and started firing. The reporter I was talking to remained still but just about everyone else hit the deck. I don't know where they came from — there were a couple of shouts. I fumbled for a camera as I tried to make myself small. The gunfire clattered round the streets like a metronome gone crazy. He fired off about six to eight shots. I fired off one. You can't tell from my picture that he was actually firing but he was. He strolled away, back to the entry. I could hear a heart beating and became aware it was my own.

The police were all over the scene in moments. The gunman was long gone. One alert BBC television cameraman had caught the gunman running away, and the moving pictures were beamed around the world. More importantly, they were seen at the other end of the Ormeau Road. Within hours the Chief Constable told the Orange Order he couldn't guarantee their safety. They called off the parade. The IRA announced a new ceasefire within weeks. In this respect, the man I had photographed was the IRA's last gunman.

The split-second of pressing the button was like a flashback to the gun battle of the earlier generation. I was older — I'd like to think wiser — but it was just as scary. Afterwards, my mouth was dry in the exact same way, due to the exact same fear. I was pleased that this time I had been able to get something, the luck of at least having the right angle to safely take a picture. Somehow I was still lying between that rock and hard place in Divis, a quarter-century earlier. The decisions about where you go when the streets of Belfast are your workplace never get much easier. There's a reason why it's called 'hard news'.

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||