Drawing Conclusions: A Cartoon History of Anglo-Irish Relations 1798-1998[Key_Events] Key_Issues] [Conflict_Background] Material is added to this site on a regular basis - information on this page may change

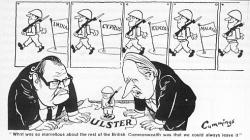

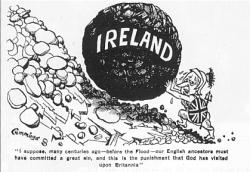

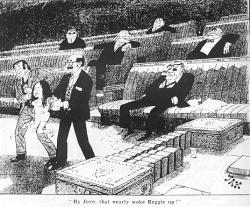

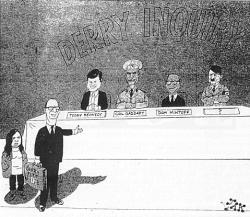

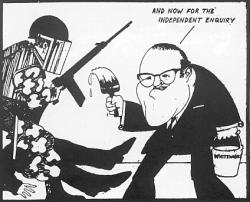

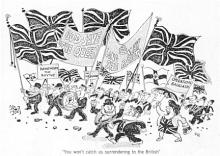

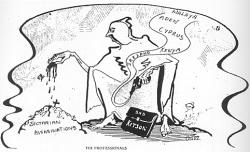

14.5 ‘What was so marvellous. . .‘, Cummings, Daily Express, London, 21 March 1971 As more troops were sent into Northern Ireland during 1971 to deal with the increasing violence, British public opinion fluctuated between advocating a much tougher security policy to ‘crack down on the terrorists’, and supporting demands for the withdrawal of troops, which opinion polls suggested was the option favoured by the majority of British people at the end of the year. The Cummings cartoon opposite shows a frustrated British prime minister, Edward Heath, and an equally frustrated home secretary, Reginald Maudling, struggling with this dilemma. (Until 1972, responsibility for Northern Ireland lay with the Home Office, and not, as now, with a separate Northern Ireland government department.) Behind them are the different colonial outposts where British troops had once been, but had eventually left or been forced to leave. The advantage of the Commonwealth, which evolved out of the empire, was that Britain could indeed leave those countries to their own governments to rule. The problem with Northern Ireland, on the other hand, was that it was an integral part of the United Kingdom, and therefore ultimately the direct responsibility of the British government. Cummings implies that Britain’s colonial history amounts to no more than a matter of simply ‘leaving’ and therefore ‘solving’ its overseas problems. This is a very patronising imperial view which takes no account of the damaging consequences of colonialism. 14.6 'Paisley ...', Izvestia, Moscow, 10 August 1971 Soviet newspapers followed events in Northern Ireland very closely in the 1970s and were highly critical of the activities of the British army, which it regarded as ‘an army of occupation’. Izvestia, one of the leading Russian newspapers, criticised the British government for allowing right-wing Protestants to attempt to revive the ‘B Special Storm Troopers’ in 1971 and alleged collusion between the army and these Protestant groups. Cartoon 14.6 gives expression to these views by depicting Ian Paisley carrying a cross which supports the gun of a British soldier, against a backdrop labelled ‘Ulster’. The Russian text at the top states: ‘The militant Protestant clergyman Ian Paisley is head of the campaign of terror and intimidation in Ulster’, while the caption underneath reads: ‘Paisley: "With us is the strength of the Cross"’. This view of the British army as an occupying force in Northern Ireland whose sympathies lay with the Protestant unionist side was a feature of newspapers in the Soviet bloc during the 1970s and 1980s. 'How to Make the Irish Stew', Scarfe, Sunday Times, London, 15 August 1971 As violence increased in 1971, few English cartoonists addressed the complicated nature of the issues which underpinned the Northern Irish problem. This tendency to over-simplify a complex situation was widespread in Britain, and goes some way towards explaining the persistence of the Troubles. Scarfe’s work was an exception. In this cartoon he attempts to illustrate some of the historical and contemporary issues which have contributed to the Troubles. He suggests that previous British governments have played a large part in creating the current crisis, and highlights other historical factors, including the Protestant plantations of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the expropriation of land by English landlords, and the Famine. He also implies that the current activities of the British army in Northern Ireland, with its use of rubber bullets and CS gas, are a key ingredient and that the army is not an impartial force. This cartoon appeared six days after the introduction of internment in Northern Ireland, which led to a huge increase in violence and many deaths. 14.8 'I suppose, many centuries ago ... ', Cummings, Sunday Express, London, 15 August 1971 On 9 August 1971 the Conservative government finally agreed to Faulkner’s demand that internment be introduced to stem the rise in violence. The fact that it was directed solely against nationalists, with no loyalist arrests being made, had disastrous results, Within three days twenty-two people were killed, thousands of Catholics fled to refugee camps in the Republic, and over six thousand people were made homeless as houses were burned down. IRA recruitment soared and the British army came to be seen as an instrument of the unionist regime by most Catholics. The failure of Faulkner’s policy and his government’s subsequent loss of credibility and legitimacy increased the probability of direct rule from Westminster. This was by no means the preferred option of Heath’s government, as this cartoon indicates. Cummings transforms Heath into a modern Sisyphus to suggest the irresolvable nature of Britain’s Irish problem. The perplexed prime minister regards Ireland as a punishment visited by God on Britain for some unspecified ancient ‘sin’. There is no suggestion that Britain’s historical and contemporary role in Ireland’s affairs might be part of the problem, but simply that this is a burden which Britannia must stoically endure. 14.9 'By Jove...', JAK, Evening Standard, London, 2 February 1972 One of the key dates in the history of the Northern Ireland conflict is Bloody Sunday, 30 January 1972. During a banned civil rights march in the city of Derry, soldiers of the Parachute Regiment shot dead thirteen unarmed men and wounded seventeen others, one of whom later died. These killings led to a wave of anger and revulsion amongst the Catholic community in Northern Ireland, and feelings in the south of Ireland ran so high that a few days later a large crowd burned down the British embassy in Dublin. Britain was also heavily criticised in the international media, and it was largely because of this incident that the British government finally decided to take over responsibility for security in Northern Ireland and suspend the unionist government at Stormont. This JAR cartoon refers to the subsequent Commons debate on the event, during which Bernadette Devlin (now McAliskey), MP for Mid-Ulster, accused Home Secretary Maudling of lying to the House and of being a ‘murdering hypocrite’ when he defended the paratroopers on the grounds that they had opened fire after snipers had fired on them. Devlin, who was an eyewitness to Bloody Sunday, then crossed the floor of the chamber, pulled his hair and struck him in the face. Until the outbreak of violence in August 1969, Devlin had been a popular figure with the British press and had been featured in several flattering cartoon poses. Aged twenty-one, she was the youngest person ever to be elected to Westminster in the modern era and presented a confident, youthful image. JAR reverses this image by depicting her as a impetuous young child who is politically immature and lacking in self - control. As she is escorted out of the chamber, patrician male figures on the Conservative benches regard her antics with humorous condescension. Yet JAR also indicts Maudling for his ineffectual handling of the situation. Well-known for his indolence, he sleeps through this physical assault, and presumably still sleeps while much of Northern Ireland seethes. 14.10 'Now that's what we call ...', JAK, Evening Standard, London, 4 February 1972 After the Bloody Sunday shootings in Derry, Heath set up a tribunal of inquiry under Lord Chief Justice Widgery. However, many northern nationalists argued that a key figure in the British establishment was an inappropriate person to head up such a sensitive inquiry and demanded that a wider, more impartial body be established, which might include international members. This cartoon savagely lampoons this suggestion. It shows Bernadette Devlin and Gerry Fitt, leader of the SDLP, indicating their preferred international inquiry team, comprising an eclectic mix of the biased and the notorious. Edward Kennedy, the well known Irish-American politician, had earlier advised the British government to leave Ireland alone; the Libyan leader, Colonel Gaddafi, was regarded as a dangerous sponsor of international terrorism and chief arms supplier to the IRA; and Dom Mintoff, the Maltese leader, was seen as a leading anti - imperialist as a result of his long struggle against British involvement in Malta. The figure of Adolf Hitler completes JAK’s shocking line-up, thereby suggesting that northern nationalists have lost all sense of proportion in their demands for a different inquiry team. 14.11 'And now for ...', Irish Times, Dublin 5 February 1972 The Irish Times cartoon conveys the scepticism with which many Irish people viewed the inquiry. The image of Maudling preparing to whitewash the British army for Lord Widgery accurately represents the prevailing sense of injustice felt by many nationalists on the publication of the Widgery Report in April 1972. By finding that the army had done its best in difficult circumstances, the judge was widely accused in Ireland of presenting a whitewash. While the report satisfied some in Britain, it left many questions unanswered in Ireland, thereby adding further fuel to the controversy which already surrounded the events of Bloody Sunday. 14.12 ‘You won’t catch us ...‘, Waite, Sunday Mirror, London, 26 March 1972 On 24 March 1972 Heath suspended the Northern Ireland government after it had refused to give up control of law and order to Westminster. The British government now became directly responsible for ruling Northern Ireland. Ulster unionists were shocked at the removal of what they regarded as their parliament and felt a deep sense of betrayal by the British government, especially a Conservative one. They immediately organised a series of mass demonstrations and strikes in protest at this action. The split between British Conservatives and unionists, who had been close allies for most of the previous eighty years, was soon complete. Keith Waite’s cartoon reveals British incomprehension at the protests of the Ulster unionists. They are shown carrying slogans which profess loyalty to the British monarchy and waving Union flags, while at the same time proclaiming their refusal to surrender to ‘the British’. The cartoon neatly captures the problematic nature of Protestant identity in Northern Ireland. Northern Protestants have traditionally proclaimed their loyalty to the British monarch, while simultaneously being prepared to oppose the actions of the government, with violence if necessary. The lack of understanding and empathy for Ulster loyalists felt by many people in Britain at the time is accurately reflected here. To them, unionists were caught in a historical time warp, and the battle of the Boyne in 1690 had little relevance to the lives of British people in the 1970s. 14.13 ‘The Professionals’, Oisín, Andersonstown News, Belfast, 30 November 1974 While most British cartoonists were largely sympathetic to the role of the army in Northern Ireland in the 1970s, it was regularly attacked in the Northern Irish nationalist press, and occasionally in loyalist publications. In this cartoon Oisin, political cartoonist of the republican Andersonstown News, parodies the well-known army recruitment slogan of the time, ‘Join the Professionals’. The army is depicted as having a bloody record of assassinations in military actions against anti-colonial campaigns in parts of the British Empire, and it is implied that the same tactics are being used in Ireland by the Special Air Services (SAS). Oisín contrasts this bloody reality with the glamour evoked by the slogan, thereby suggesting that the army is little more than a body of mercenaries. Brigadier Frank Kitson was a key figure in the British army leadership in Northern Ireland at the time and was a leading expert on counter-insurgency and covert operations. He had experience of similar campaigns in Kenya, Malaya and Cyprus, and was the béte noire of Irish republicans, who accused his troops of engaging in selective assassinations in Northern Ireland.

|

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||