Drawing Conclusions: A Cartoon History of Anglo-Irish Relations 1798-1998[Key_Events] Key_Issues] [Conflict_Background] Material is added to this site on a regular basis - information on this page may change

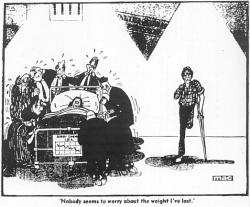

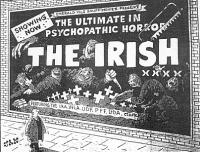

One of the bloodiest days of the current Troubles was 27 August 1979, when Earl Mount-batten, a relative of Queen Elizabeth, and three other people were blown up on their boat by an IRA bomb at Mullaghanore, County Sligo, in the Irish Republic. Born in 1900, Mountbatten had been supreme Allied commander in south-east Asia during the Second World War, and later the last viceroy of lndia. On the same day as he died, eighteen British soldiers were killed by IRA bombs near Warrenpoint, County Down, the army’s highest loss of life in any single day of the Troubles. 14.14 Untitled, Hill, Detroit News, Detroit, 29 August 1979 The dramatic American cartoon opposite graphically illustrates how the IRA had that day succeeded in inflicting a deep wound in the spine of the imperial British lion. The lion roars in pain on the cliffs of Mullaghmore, while in the background a Union Jack flies at half-mast on Windsor Castle. Though Mountbatten was not a figure of any real power, to the IRA he was an important imperial and establishment symbol. His death received worldwide publicity and the IRA was widely condemned for its actions that day. In June 1972 the Conservative Northern Ireland secretary, William Whitelaw, granted ‘special category’ status to republican prisoners and others associated with paramilitary organisations. This was a tacit recognition by the government that such people would not be in prison but for the political situation in Northern Ireland. They were not required to work, wore their own clothes and effectively organised their own lives in prison. In March 1976 Whitelaw’s Labour successor, Merlyn Rees, announced the removal of this status and decreed that in future all such prisoners would be treated as ordinary criminals. Republican prisoners refused to co - operate with this removal of special status and boycotted prison work and the wearing of prison uniform. Instead they wrapped themselves in blankets and later began a ‘dirty protest’. This lasted until March 1981, by which time the focus of republican attention had shifted to Bobby Sands’s hunger strike. 14.15 ‘Notes', Cormac, Republican News, Belfast, 7 June 1980 Cormac’s cartoon strip (14.15) in this staunchly republican newspaper attacks the authorities’ attempts to criminalise those who regard their crimes as political and who were convicted in special non-jury courts. He illustrates the inconsistency and hypocrisy of applying special legal measures to such suspects up to the point of conviction, after which they are then categorised as ordinary criminals. Shortly after the hunger strike ended, the government conceded the right of these prisoners to wear their own clothes and eventually granted virtually all of their other demands. 14.16 ‘Nobody Seems to worry ...', Mac, Daily Mail, London, 24 April 1981 On 1 March 1981 the leader of the Provisional IRA in the Maze prison, Bobby Sands, began a hunger strike aimed at securing for republican prisoners the political status which had been removed in 1976. He was gradually joined by other prisoners, and on 9 April won the Fermanagh - South Tyrone by-election to the Westminster parliament. With a turnout of over 86 per cent, Sands obtained 30,492 votes to Ulster Unionist Harry West’s 29,046. This gave a major boost to the hunger-strike campaign and increased the pressure on the British government to make concessions. There was little sympathy in Britain for the hunger-strikers’ demands, as the Daily Mail cartoon opposite shows. It features an ailing Sands, surrounded by grieving visitors, including a priest, while a victim of IRA violence stands alone, his suffering quickly forgotten. Most British cartoons at the time emphasised the plight of victims of IRA violence, rather than that of the hunger-strikers, who were acting of their own free will. Although the British government did not concede the prisoners’ demands immediately, and ten of the hunger - strikers were to die, the net result of the campaign for Sinn Féin was a significant gain in electoral and moral support among northern Catholics. During the hunger strikes, the SDLP took the controversial decision not to contest the by - election against Sands, so as to avoid splitting the nationalist vote in the constituency and risk losing the seat to the Ulster Unionists. The hunger strikes had become a national election issue and the SDLP believed that it would have been politically difficult for them to have run a candidate against a starving man in a prison hospital. Sands died on 5 May after sixty-six days on hunger strike and a second by - election was necessary. In June the British parliament passed new legislation preventing prisoners from standing for election. Sinn Féin responded by nominating Sands’s election agent, Owen Carron, who won the seat with an increased majority on 20 August. Once again, the SDLP did not contest the seat. 14.17 ‘Fermanagh South Tyrone ...', Friers, Irish Times, Dublin, 8 August 1981 Cartoon 14.17 by Rowel Friers, one of Northern Ireland’s best-known cartoonists, illustrates the danger which the SDLP was courting by such a policy. Its leader, John Hume, is shown shielding his colleagues Paddy O’Hanlon, Seamus Mallon and Austin Currie, while Carron paddles Sands’s coffin through the ‘dangerous marshland’ of post-hunger-strike politics. The cartoon expresses the fear that Sinn Féin might successfully challenge the SDLP's position as the principal voice of northern nationalism. This did in fact happen soon afterwards when Sinn Féin announced its decision to contest Northern Ireland and Westminster elections. It was the beginning of the policy of ‘the Armalite and the ballot box’, through which Sinn Féin won significant Catholic support, obtaining over 13.4 per cent of the vote in June 1983, which compared favourably to the SDLP’s 17.9 per cent. 14.18 ‘The Right Loyal-Pest', Blotski, Fortnight, Belfast, December 1981 In autumn 1981 unionists felt that they were being increasingly ignored, and that the political agenda was being set by the British and Irish governments. They feared that their interests would he sold out by London as part of a deal with the Irish Republic and argued for a much stricter security policy to counter escalating IRA violence. Their anger increased when, on 14 November, the IRA killed Robert Bradford, a staunch Ulster Unionist MP and friend of Ian Paisley. Paisley reacted by setting up a pseudo - paramilitary group called the ‘Third Force’ to protect the Protestant population, and claimed in December that it had over fifteen thousand men at its disposal. On 23 November his supporters organised a ‘Day of Action’ to protest against the security policy of Northern Ireland Secretary James Prior, with rallies and work stoppages in Protestant areas. The Blotski cartoon opposite is a parody of Tenniel’s ‘The Fenian-Pest’ which appeared in Punch on 3 March 1866 (see cartoon 5.1, p. 67). Whereas Tenniel demonised the Fenians for their revolutionary presumption, Blotski simianises Paisley’s loyalist mob for threatening violent action. The Britannia figure of Margaret Thatcher has no sympathy with their antics and, it is suggested, will crush them if necessary. Thus, militant Ulster loyalism has become just as threatening to the British and Irish governments as militant Irish republicanism. In 1970 a group of IRA veterans of the Anglo-Irish War, who had been living in America for many years, met with prominent members of the Provisionals in the United States. The result was the formation of Irish Northern Aid (Noraid), whose object was to collect money in America for republican organisations and individuals in Ireland. It won the support of many Irish-Americans and raised substantial sums of money, particularly during the Maze hunger strike, which had a powerful emotional appeal to a large section of the Irish community there. Most of this money was spent on helping the families of IRA activists, although both London and Dublin accused it of being simply a front organisation to enable weapons and explosives to be bought by the IRA. Undoubtedly some of the money was used for these purposes, though most of the money which purchased weapons in America was channelled through other sources. 14.19 ‘Give us the tools ...', Garland, Daily Telegraph, London, 21 July 1982 Nicholas Garland’s sketch (14.19) criticises Irish - American financial support for IRA activity by effective use of historical analogy. The cartoon parodies Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s request for American money and weapons to aid the fight against Nazi Germany in 1940, prior to the United States entering the war. It shows a blood-soaked IRA gunman issuing a similar request for American aid in 1982, as menacing clouds gather over Ireland. Uncle Sam appears hesitant, however, pondering the potential consequences of his support. 14.20 ‘The Irish', JAK, Evening Standard, London, 29 October 1982 This JAK cartoon caused a great deal of controversy in both Britain and Ireland when it was published in London’s Evening Standard newspaper in the autumn of 1982. It appeared at a time when paramilitary violence showed no sign of abating and when Anglo-Irish relations were still strained as a result of the southern government’s ‘neutral’ attitude towards Britain during the Falklands War. In July, two IRA bombs in London had killed eight people and injured over fifty others. On 27 October, three RUC officers were killed in a massive explosion in Lurgan, County Armagh. All these events may have influenced JAK’s decision to draw this offensive cartoon, though none can excuse that fact that it represents one of the most appalling examples of anti - Irish cartoon racism since the Victorian era. It shows a man nervously walking past a poster advertising the latest x - rated film from ‘Emerald Isle Snuff Movies’, ‘The Irish’, featuring a cast of degenerate nationalist and loyalist paramilitaries, whose initials appear at the bottom of the poster. Not only is there no attempt to explain Irish political complexities or distinguish between different paramilitary groups, the cartoonist irresponsibly homogenises the Irish as a race of psychopathic monsters who delight in violence and bloodshed. No doubt this reflected the attitude of some in Britain who had little interest in trying to understand contemporary Irish politics, and preferred to brand all Irish people as murderous thugs. As a result of complaints made by many people in Britain, the Greater London Council, under its leader Ken Livingstone, withdrew its advertising from the Standard and demanded a full apology, which was refused. The Press Council later rejected criticisms of the Standard and instead condemned the GLC for attempting to coerce the paper’s editor.

|

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||