Drawing Conclusions: A Cartoon History of Anglo-Irish Relations 1798-1998[Key_Events] Key_Issues] [Conflict_Background] Material is added to this site on a regular basis - information on this page may change The following chapter has been contributed by the authors, Roy Douglas, Liam Harte and Jim O'Hara, with the permission of the publishers, The Blackstaff Press. The views expressed in this chapter do not necessarily reflect the views of the members of the CAIN Project. The CAIN Project would welcome other material which meets our guidelines for contributions.  This chapter is taken from the book:

This chapter is taken from the book:

Drawing Conclusions

Orders to local bookshops or:

This publication is copyright Roy Douglas, Liam Harte and Jim O'Hara (1998) and is included on

the CAIN site by permission of Blackstaff Press and the authors. You may not edit, adapt,

or redistribute changed versions of this for other than your personal use

without express written permission. Redistribution for commercial purposes

is not permitted.

From the back cover: The first major study of Anglo-Irish relations to use political cartoons as a basis for historical and cultural analysis, covering the two centuries from the 1798 United Irishmen Rising to the 1998 Good Friday Agreement. Political cartoons often expose a nastier underside to contentious issues than is apparent on the surface of polite society. This is especially true of cartoons dealing with the long-running Irish question, many of which feature harsh cultural stereotypes. Here the unique value of cartoons as historical evidence is revealed and analysed, particularly for what they divulge about the prejudices of cartoonists and their target audiences. Over 250 cartoons - graphic, witty, sometimes downright vicious - are reproduced from British, Irish, European and American sources. Each is accompanied by an informative explanation of the historical context and further depth is provided by lucid, concise accounts of each key period. Essential reading for anyone interested in the complexity and nuances - past and present - of the relationship between Ireland and Britain.

14

[Section 1] [Section 2] [Section 3] [Section 4] In the winter of 1968-69 the Northern Ireland prime minister, Terence O’Neill, came under increasing pressure from three sources. First, the predominantly Catholic civil rights movement was demanding widespread reform of the state to end the gerrymandering of electoral boundaries, to allocate public housing on a fair basis, to disband the B Specials and to introduce ‘one man, one vote’ in local council elections. Second, there was a growing number of unionist critics of O’Neill, the most extreme of whom was the Reverend Ian Paisley, who feared that O’Neill’s concessions to the nationalist minority were weakening the unionist position. Third, Wilson’s Labour government in Britain was beginning to grow more concerned about the increasing unrest in Northern Ireland. On 4 January 1969 a march from Belfast to Derry organised by students at Queen’s University Belfast and other civil rights supporters was attacked by some two hundred loyalists, including members of the B Specials. That night, amid widespread unrest in Derry, the police went on the rampage in the Catholic Bogside area of the city. Sectarian passions were rising to a level unknown for many years and undermining any goodwill that O’Neill’s modest reforms had earned him from the nationalist population. Ultra-loyalists like Paisley and some within O’Neill’s own party saw the civil rights movement as a republican plot aimed at bringing down the northern state, not merely reforming it. In desperation, O’Neill called a general election in February, hoping to strengthen his hand, but the splits within unionism widened, and his own position was further undermined by the relative success of more hardline loyalist candidates. Of the 52 seats in the Stormont parliament, unionists won 39, but 10 of these went to anti-O’Neillites, with 2 undecided. O’Neill resigned in April, a beaten man, to be replaced as prime minister by his cousin, the lacklustre figure of James Chichester-Clark (1923 - ). To add insult to injury, O’Neill’s seat at the subsequent by-election was won by his arch-enemy, Paisley. Sectarian clashes grew more frequent during the summer of 1969. British civil servants sent over to Belfast from London to oversee reforms were totally unfamiliar with the political culture, historical complexities and sectarian passions which confronted them. The heightened tension during the traditional Orange marches in July led to rioting in Belfast, but the climactic moment of no return occurred in Derry in August, following disturbances during a Protestant Apprentice Boys’ march in the city. The B Specials played a critical role in these events. They attempted to enter the Catholic Bogside area but were prevented by the residents who, believing that their homes were about to be attacked, erected barricades and hurled petrol bombs at the police. Three days of serious rioting followed, and this spread to Belfast where Protestant mobs attacked Catholic areas of the city, sometimes assisted by armed B Specials. It was soon clear that the Northern Ireland police was incapable of subduing the violence and maintaining law and order. During the night of 14 August, 6 people died as a result of the riots and over 400 houses were severely damaged. On the same date, the Labour government reluctantly took the decision to send in British troops to restore order. They were greeted warmly by the Catholic population, who saw them as saviours, infinitely preferable to the armed police, while Protestants looked on hesitantly, realising that the unionist regime was no longer sole master of its own house. The presence of British troops on the streets of Belfast and Derry was to change fundamentally the nature of the Northern Ireland problem. Having ignored the state it created for almost fifty years, an ill-prepared British government was now dragged into its affairs, with little thought being given to the long - term implications. There was uncertainty amongst all groups as to whether the army was there to protect the Catholic population, to subdue revolution, or to shore up a discredited regime. The officer commanding British troops, Lieutenant - General Sir Ian Freeland, perceptively warned that the initial ‘honeymoon period between troops and the local people is likely to be short-lived’. Wilson’s government, which now had effective overall responsibility for maintaining order, continued to work through the unionist government at Stormont in the unrealistic hope of keeping the northern problem at a distance. The expectation was that the army would be able to keep the peace while some reforms were made to the running of the state, and that normality would resume under a reorganised unionist government. However, the short-term reforms which Wilson’s government forced the Northern Ireland administration to concede only served to antagonise further many Protestants, and failed to reconcile Catholics, a growing number of whom were coming to regard Northern Ireland as a ‘failed political entity’ and to see security and justice in a new united Ireland. The IRA had been much criticised in some Catholic areas for its failure to defend besieged Catholic communities during the rioting of August 1969. In January 1970 it split into two groups. The Official IRA, the so - called ‘Red’ faction, retained its socialist objectives, but a breakaway group, the Provisional or ‘Green’ IRA, soon became the dominant body. The movement quickly established itself in Catholic housing estates and spent much of 1970 training its volunteers and acquiring weapons. The Provisionals’ aim was to drive the old enemy, the British army, out of Northern Ireland and to bring about the unification which had been denied them in 1921. Gradually, the IRA began to attack British troops and the first soldier was killed in February 1971. By this time the Labour government in Britain had been replaced by Edward Heath’s Conservative administration, which tended to see the IRA as the basic problem together with the Catholic community which gave it active or tacit support. This new emphasis on a security response to what was a political problem further alienated Catholics from the British government and its unionist allies at Stormont, and led to the army being perceived in Catholic housing estates as an army of occupation, which was exactly what the Provisionals were arguing. In August 1971 the London government made the disastrous decision to accept the Northern Ireland government’s advice and introduce internment without trial for IRA suspects. Internment was very much a one-sided operation against the nationalist population. No loyalists were included among the 342 men arrested. Many innocent people were detained, internees were brutalised and tortured, violence escalated and Catholic disenchantment deepened. Indeed Catholic and Protestant fears were such that there was a massive movement of people to ‘safe areas’, producing the largest enforced population movement in Europe since 1945. The final straw came on 30 January 1972 when British paratroops killed thirteen unarmed civilians during a civil rights march in Derry, on what became known as Bloody Sunday. The British government, having tried to work through the Stormont regime, finally realised that it would have to accept full responsibility for policy in Northern Ireland. Accordingly, in March 1972 Heath’s government suspended the Northern Ireland parliament and established direct rule from London through a Northern Ireland secretary of state. Initially intended as a temporary measure, direct rule was to become a permanent feature of the state. The fall of Stormont was regarded by unionists as a victory for the Provisional IRA. Many Protestants felt betrayed by Britain and felt very deeply insecure about their future. A number of paramilitary organisations were formed in Protestant working - class areas to counter - balance the activities of the Provisionals and carry out attacks on Catholic areas. As the IRA increased its campaign of shootings and bombings, 1972 became the most violent year of the Troubles with 467 deaths in Northern Ireland, 321 of which were civilian casualties. Catholic political self - confidence was growing, particularly as the British government was coming to accept the fact that the nationalists’ aspiration towards unity required formal acknowledgement, and that the Dublin government might in some way be involved in an overall solution. The core problem for the British government, however was how to reconcile the opposing interests of nationalists and unionists. In both groups there were different factions. Within nationalism, those republicans represented by Sinn Féin saw the British presence as the key problem and refused to participate in constitutional politics, while more moderate nationalists, represented by the SDLP, were willing to co-operate with the government to reform the northern state. Within unionism, extreme loyalist groups objected to concessions to nationalists, and to the involvement of the Dublin government in northern affairs, which they considered would weaken the link with Britain. For a great many years, Northern Ireland unionists had co-operated so closely with British Conservatives that they were, for practical purposes, one party. In the early 1970s, however, the unionists broke this alliance and became a separate force in United Kingdom politics. In 1971 the previously monolithic Ulster Unionist Party had split when Ian Paisley broke away to form the Democratic Unionist Party. The DUP, although smaller in numbers than the ‘official’ unionists, was dominated by the imposing figure of Paisley and adopted extreme positions on most matters. Its roots were more working class than those of the Ulster Unionists, and its members tended on the whole to be Presbyterian, while the ‘officials’ represented a broader range of Protestantism, including a higher proportion of members of the Church of Ireland. By 1972 it was apparent to the British government that military measures alone could not solve the problem and so during the next twenty - five years a series of political initiatives was attempted. All of these took place against a background of killings and bombings in Northern Ireland and Britain, while successive governments sought to contain the political violence through emergency legislation. The first major initiative took place in November 1973 when the British government, while guaranteeing Northern Ireland’s position in the United Kingdom, proposed to set up an elected Executive in which power was to be shared by moderate unionists and nationalists. A Council of Ireland was also proposed, which would allow Dublin an ill-defined role in Northern Ireland affairs. There was, however, much unionist opposition to these proposals, and in particular to the Council of Ireland, which was seen as a threat to the Union. Amid increasing unrest, groups of loyalist workers, calling themselves the Ulster Workers’ Council, declared a general strike in May 1974. They were aided by loyalist paramilitary groups such as the Ulster Defence Association. Despite widespread intimidation, Wilson’s new Labour government was unwilling to use the army to break the strike and support the power-sharing Executive. The result was the ignominious collapse of the five-month-old Executive on 28 May 1974, and a confirmation of loyalists’ belief that they could effectively destroy by force any political plan put forward by Britain which they opposed. For the rest of the l970s there was little sense of plan or purpose to British policy in Northern Ireland, but rather a further emphasis on security measures. In 1973 the IRA took its bombing campaign to England. Following major bombings in London, Guildford and Birmingham, the Labour government rushed through the Prevention of Terrorism Act in 1974, part of which enabled the authorities to ban suspected terrorists from entry into Britain and to banish them to Northern Ireland, although still an integral part of the United Kingdom. Within Northern Ireland itself, the mid - 1970s saw an increasingly vicious series of bombings and ‘tit-for-tat’ sectarian murders. In an attempt to restore the appearance of normality, the British government adopted a new strategy of ‘Ulsterisation’ in 1976, whereby the prominent role of the army was replaced by an emphasis on the primacy of the RUC. In 1976 ‘special category’ (political) status for paramilitary prisoners was also removed in an attempt to criminalise those convicted of political offences. This move precipitated a grave crisis in the prisons which came to dominate northern politics in the late 1970s. Republican prisoners, demanding political status, refused to wear prison clothes and went on a ‘blanket protest’, later followed by a ‘dirty protest’. Finally, in March 1981, they began a series of hunger strikes in their H - Block cells in the Maze prison near Belfast in order to regain political status. The hunger strikes provided a huge public platform for the Provisional movement, and its political wing, Sinn Féin, achieved worldwide publicity when the leader of the hunger-strikers, Bobby Sands, was elected as a British MP in April. His election revealed levels of support amongst the nationalist community far beyond that usually associated with revolutionary republicanism. The prolonged fasting and dramatic deaths of Sands and nine other hunger-strikers in 1981 further increased the publicity for republicans in America and Europe, and greatly increased the level of their support from nationalists. The Conservative prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, leader of the government elected in 1979, had been determined not to give in to the pressure exerted by the hunger-strikers and their supporters. She resisted their demands until they finally capitulated, but this was a classic case of how to win a battle yet lose the war. Britain’s handling of the affair was disastrous. It encouraged the Provisionals to attempt to capitalise on their increased support by entering the political arena and contesting elections. The new Provisional strategy was aimed at taking power in Ireland ‘with a ballot box in one hand and an Armalite in the other’. The growing success of Sinn Féin at both local and national elections led to government fears that the moderate SDLP would be replaced as the main voice of Catholic nationalism in Northern Ireland. These fears were increased when Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams (1948 - ) won the West Belfast seat in the Westminster general election of June 1983. As political agreement between the parties within Northern Ireland seemed impossible, Britain looked to the Irish government to share the problem, and sought to find agreement between the two governments on the way forward. On the surface, the years between 1980 and 1985 produced little progress and there was a number of public disagreements between the two governments. To make matters worse, in October 1984 at the Conservative Party conference in Brighton, there was an almost successful IRA attempt to assassinate Margaret Thatcher and members of her cabinet when a bomb exploded in their hotel. However, behind the scenes, officials of both governments had been working together to produce a historic understanding which was signed by the two premiers, Garret FitzGerald and Margaret Thatcher, on 15 November 1985. The Anglo-Irish Agreement, whilst guaranteeing that Northern Ireland would remain part of the United Kingdom as long as a majority of the population so desired, had the fundamental importance of granting Dublin a permanent consultative role in the affairs of Northern Ireland for the first time since 1921. This willingness to share decision-making powers with the southern government marked a decisive shift in British government thinking. Republicans opposed the agreement because of its continuing support for the Northern Irish state, while unionists were outraged at the way they had been excluded from the two governments’ negotiations. In December 1985 all fifteen unionist MPs resigned their Westminster seats in order to fight anti - agreement by - election campaigns under the slogan ‘Ulster Says No!’ The following March, a unionist Day of Action brought the province to a standstill. The agreement, however, was widely welcomed in the rest of Ireland, Britain and the international world. Despite the widespread, prolonged, and sometimes violent loyalist opposition, the agreement remained secure. This time the British government did not capitulate to loyalist opposition as it had done in 1974. Despite this inter - governmental consensus, violence still occupied the centre stage. Allegations of a ‘shoot-to-kill’ policy by the security forces in Northern Ireland were followed by a huge IRA bomb in Enniskillen on Remembrance Day, November 1987, which killed 11 civilians and left over 60 injured. There were also increased killings by Protestant paramilitaries, and three unarmed IRA volunteers were shot dead by British soldiers in Gibraltar in March 1988. However, the appointment of Peter Brooke as Northern Ireland secretary of state in July 1989 produced a fresh political initiative. Shortly after taking office, Brooke made a number of important speeches in which he indicated that the government would talk to Sinn Féin if the IRA renounced violence; that Britain’s role in Northern Ireland was a neutral one; and that Britain would accept Irish unification if a majority of the people in Northern Ireland consented to it. Since 1988 there had also been dialogue between John Hume and Gerry Adams, which attempted to draw Sinn Féin into the political arena. Through its association with the SDLP, Sinn Féin was hoping to establish a broadly based nationalist movement which would have the support of the Dublin government. Furthermore, between October 1990 and November 1993 there were secret contacts between British government officials and leading Sinn Féin figures such as Martin McGuinness, a sign that the British authorities were privately conceding the importance of involving Sinn Féin in political dialogue. Considerable rethinking had also been occurring within the Provisional movement itself, with a growing emphasis being placed on seeking political legitimacy as opposed to a continuation of the armed struggle. In 1991 Brooke succeeded in getting talks started between all the constitutional parties in Northern Ireland, excluding Sinn Féin. There were three separate strands to these talks: internal relations within Northern Ireland; arrangements between Northern Ireland and the Dublin government; and relations between London and Dublin. These talks continued until November 1992 under a new Northern Ireland secretary, Sir Patrick Mayhew. Although they failed to reach agreement on any of the three strands, they had established an agenda for future negotiations where ‘nothing would be agreed in any strand until everything is agreed in the talks as a whole’. Meanwhile, sectarian murders and bombings continued. The steady rise in loyalist paramilitary violence resulted in the random assassination of Catholics, while in April 1992 the IRA exploded a huge bomb at the Baltic Exchange in the centre of London, which killed three people and caused damage amounting to hundreds of millions of pounds. Despite this violence, the secret and overt political activity of the previous years within Northern Ireland, together with the continuing co-operation between the British and Irish governments, were leading to the possibility of dramatic political movement towards an Anglo-Irish peace process. 14.1 'Coming in? It's terrible!', Gibbard, Guardian, London, 5 August 1969 During the early part of 1969 political tension increased in Northern Ireland as civil rights activists continued to clash with the RUC. The beginning of the summer marching season in July led to serious rioting in a number of areas, and the fear that the Protestant Apprentice Boys’ parade in Derry on 12 August would provoke serious conflict. Both the prime minister, Harold Wilson, and the home secretary, James Callaghan, were very reluctant to intervene, fearing that once involved it would be very difficult for the British government to extricate itself easily. Callaghan later stated: ‘The advice that came to me from all sides was on no account to get sucked into the Irish bog. Most British newspapers showed little real understanding or analysis of the issues in Northern Ireland, and often identified religious fanaticism as the source of the problem. This Guardian cartoon reflects this British ignorance. Based on the classical legend of Laocoön, who was crushed to death by two sea-serpents sent by Apollo, it shows a helpless Northern Ireland premier, James Chichester - Clark, trying to keep apart two sectarian sea monsters. The diffident, avuncular figure of Wilson is dressed for his swim in the Ulster sea, but is clearly thinking twice about the wisdom of so doing. Not until he was compelled by the complete breakdown of law and order nine days later did Wilson brave the treacherous waters by finally ordering troops into Northern Ireland, thereby directly involving the British government for the first time since 1921.

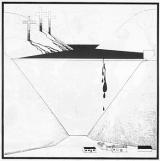

14.2 'We're pagan missionaries …', Cummings, Daily Express, London, 12 September 1969 When the army first arrived in Northern Ireland the troops were warmly received in Catholic areas, in the belief that the soldiers had come to save them from the aggression of the B Specials and the RUC. However, as the officer commanding British troops in Northern Ireland had warned, this honeymoon period was not to last, and soon Catholics in working - class areas came to see the army as an instrument of the Stormont regime. British cartoonists in the popular press frequently depicted the army as a benign, dispassionate presence, bemused by the tribal antics of the natives. Religion was supposed to be at the core of the problem, and few in Britain could easily understand why two different strands of Christian belief should lead to such violent conflict. This Cummings cartoon reflects this British incomprehension in its depiction of primitive tribesmen arriving to reconcile the barbarous Irish, who seem intent on tearing each other apart. The racist implication is that black, presumably African, tribesmen are more civilised than the Christian Northern Irish, who have now slipped below even primitive pagans in their innate barbarity. The cartoon thus reinforces stereotypical notions of the Irish as violent and blacks as primitive, and makes no attempt to convey any understanding of the underlying causes of conflict other than religious bigotry. The Cummings cartoon opposite, published a year later, when Catholic resentment towards the army had increased and Provisional IRA violence had begun, continues to portray the army as a neutral peace-keeping force. It reflects a growing impatience among some sections of the British public with the conflict in Northern Ireland and their desire for the army to withdraw and leave the Irish to fight it out among themselves. A bruised British soldier attempts to separate two violent Irishmen, whose simian features suggest a direct lineage with the apelike Paddys in Punch one hundred years earlier. In fact, Cummings later commented that the IRA’s violence tended to ‘make them look like apes - though that’s rather hard luck on the apes’. The implication underlying both cartoons is that the irrational nature of the Irish question can only be explained through some form of racial madness. Far from helping British readers to understand the complexities of the Northern Irish situation, such cartoons reinforced the growing anti - Irish prejudice among sections of British opinion and so exacerbated the hostile public mood. 14.3 'How marvellous it would be …', Cummings, Daily Express, London, 12 August 1970 At the end of 1969 a split in the IRA took place, leading to the birth of the Provisional movement. During 1970 relations between Catholics and Protestants continued to deteriorate and IRA attacks on the police and army began. On 6 February 1971 the first British soldier was killed, and a month later three off-duty Scottish soldiers, two of them brothers aged seventeen and eighteen, were lured from a Belfast pub and shot by the Provisionals. A week later as the security situation worsened, Chichester - Clark resigned and was replaced by Brian Faulkner. who was to become the last prime minister of Northern Ireland. 14.4 Untitled, Scarfe, Sunday Times, London, 14 March 1971 Gerald Scarfe’s cartoon is a powerfully dramatic comment on the killing of these three soldiers on an Irish hillside. He dramatises the popular cliché of ‘the rising tide of violence’ by showing drops of blood dripping from a crack in a dam onto a peaceful community below. Scarfe’s ominous warning of the flood of bloodshed that threatened to swamp the state proved to be chillingly prophetic, as the dam did burst the following year, 1972, when the highest number of deaths during the Troubles was recorded. The parallel between the crosses on Calvary and the three dead Scots adds to the stark power of the image.

|

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||