Extracts from 'The British Media and Ireland - Truth: the first casualty'[Key_Events] Key_Issues] [Conflict_Background] MEDIA: [Menu] [Reading] [Summary] [Background] [Chronology] [Main_Pages] [Resources] [Sources] Material is added to this site on a regular basis - information on this page may change REPORTING NORTHERN IRELAND This article first appeared in Index on Censorship, Vol. 7, No. 6, London 1978. Since writing the following ‘Index’ article in July last year, much of the dust raised by the series of clashes between broadcasters, their institutions and government, has settled. The issues, however, remain unresolved. The atmosphere may be clearer but the climate has undoubtedly changed. Now to continue to investigate sensitive areas like the H Blocks, requires a degree of political footwork that would have been unthinkable over a year ago before the outbreak of hostilities between the media and their masters began in the summer of 1977. Programme makers and programme vetters now proceed with a caution born of the events documented in ‘Index’; the broadcasters of necessity to ensure the transmission of their material despite the compromises that now may entail; the censors anxious to avoid a repetition of the Amnesty fiasco where the banning of a programme not only drew greater attention to its content but threw into sharp relief the restrictions inherent in reporting Northern Ireland. No other domestic or foreign political issue is beset with the pressures that journalists face when they attempt to report, analyse and place in perspective the most pressing political issue on their doorstep. Returning from Rhodesia recently with a report that challenged some of the perspectives of the war there, I ran into none of the problems that have attended my reporting of Ireland nor did I expect to, Rhodesia remains faraway. Ireland is too close to home. Writing in this journal six years ago, Anthony Smith warned that the solidification of relationships and the delineation of tensions which the Irish question had imposed on the institutions of broadcasting were likely to develop in the next decade. His words were prophetic. Whereas few can have been surprised at the gradual unfolding of these relationships as the Irish conflict steadfastly defied resolution and journalists persisted in asking nagging questions - albeit too few and too seldom - the sudden acceleration of the process in the past year has alarmed all parties, not least the journalists whose work is under attack. Nowhere, in the British context, has the relationship between state, broadcasting institutions and programme makers been more sensitive and uneasy than in matters concerning Northern Ireland. Conflict arises whenever broadcast journalism challenges the prevalent ideology embodied in government policy and reflected in the broadcasting institutions it has established. In principle, the broadcasting authorities should stand between the media and the state as benevolent umpires, charged with the task of defending each against the excesses of the other, guardians of the public interest, upholders of a broadcasting service alleged to be the finest in the world. In practice, where Northern Ireland is concerned, they have become committed to a perspective of the conflict which identifies the public interest increasingly with the government interest. To question the government’s ideology is to court trouble. The deeper the crisis and the more controversial the methods used to meet it, the greater the strain on the institutions of broadcasting forced to choose between the journalist’s insistence on the public’s right to know everything and the government’s preference for it not to know too much. The Irish question hangs over British politics like an angry and stubborn cloud that refuses to go away, despite the insistence of successive generations of British politicians that the cloud is just passing. The cloud has been there for 400 years. The words of British politicians from Robert Earl of Essex, servant of Elizabeth the First, to Roy Mason, servant of Elizabeth the Second, echo down the centuries voicing frustration with and issuing warnings to the Irish that have changed little over four centuries. The shadow of the current ten-year cloud under which we stand is no longer and darker than its predecessors. Northern Ireland is different, not because there is no consensus but because the nature of the consensus that exists makes any informed discussion of the problem difficult, if not increasingly impossible. The official consensus runs something like this: Northern Ireland is a state in conflict because Catholics and Protestants refuse to live together despite the efforts of successive British governments to encourage them to do so: we (the British), at considerable cost to the Exchequer and our soldiers, have done all that is humanly possible to find a political solution within the existing structures of the Northern Irish state: now the two communities must come up with a political solution they are prepared to work and accept themselves: the terrorists, in particular the Provisional IRA, are gangsters and thugs: they are the cause, not the symptom of the problem. This is, of course, a British mainland perspective. Others see it differently. When Jack Lynch, the Irish Prime Minister, suggested that Britain should withdraw from the North and encourage the reunification of the country, Westminster - and much of Fleet Street - was outraged at his impertinence in suggesting such a solution to a ‘British domestic problem’. To challenge these cosy assumptions about the conflict - deliberately fostered by those in high places either because they are convenient or because they believe them - is to run the risk of being branded at best a terrorist dupe, at worst a terrorist sympathiser. Journalists and politicians rash enough to dissent have felt the lash of tongues from both sides of the House of Commons and been called ‘unreliable’. Yet some of us working there as journalists have come to believe that the conflict is political and not religious: that its origins lie in the conquest of Ireland by England and the subsequent establishment of a Protestant colony in Ulster to keep the province secure for the Crown; that the immediate conflict stems from the partition of the country 50 years ago, an artificial division designed to be only temporary, engineered by the British to guarantee Protestant supremacy in the remaining six counties of Ulster; that the Provisional IRA may lay claim to the mantle of the ‘terrorists’ who drove the British out of the 26 counties in 1919-20 in a campaign every bit as bloody and unpleasant as the IRA’s current offensive to drive the British from the remaining six counties; and lastly (and currently most sensitive of all) that not all the RUC’s policemen are wonderful. Why has the issue come to a head over the past twelve months? The last great battle was fought by the BBC in late 1971 over ‘A Question of Ulster’, which the Corporation succeeded in transmitting despite enormous pressure from the Unionist government at Stormont and the Tory government at Westminster. The marathon programme was notable more for the fact of its transmission than its content. It was hailed as a victory for the Corporation’s independence, but as Philip Schlesinger has pointed out, it was a success story amidst general defeat, for had the BBC not resisted the political pressures, it would have undermined its own legitimacy and public confidence in the institution. In the years that followed, Northern Ireland was gradually relegated to the second halves of the news bulletins and the inside columns of the newspapers. Ulster ceased to be a story. When the media did return to the subject, coverage continued to be guided by the numbing principles outlined by Philip Elliot in his UNESCO report, that the story should be simple, involving ‘both lack of explanation and historical perspective’; of human interest, involving ‘a concentration on the particular detail of incidents and the personal characteristics of those involved which results in a continual procession of unique, inexplicable events’; and lastly, a reflection of the official version of events to consolidate the ‘production of a common image’. But there were occasional squalls in spite of the media’s generally low profile. In 1976 the IBA banned a ‘This Week’ investigation into IRA fund raising in America before a foot of film had been shot, not because the subject matter was particularly contentious but because the ‘timing’ was felt to be wrong. The film was transmitted a week later, but it was a warning shot. Meanwhile, Merlyn Rees, Secretary of State for Northern Ireland until the summer of 1976, negotiated the ending or internment and a cease-fire, his patience and persistence winning the respect of the public - even some Provos with whom he was brave enough to negotiate - and the goodwill of journalists. We felt that he was trying. His successor, however, Roy Mason, was a man hewn from rougher rock. His acquaintance with Ireland had begun as Minister of Defence (a position unlikely to encourage perspectives when the Army was faced with its closest and most pressing security problem since the war). For him the problem was one of security and the present, not politics and the past: results were what he wanted, not history lessons or the niceties of media philosophy as expressed by the BBC’s then Controller of Northern Ireland Dick Francis in 1977:

Under Mason, journalists were more than ever courted as allies in the war, not recorders of it. After only a few months in office the new Secretary of State is reported to have made his position brutally clear to Sir Michael Swann, Chairman of the BBC, at a private dinner at Belfast’s Culloden Hotel, where he accused the BBC of showing disloyalty, supporting the rebels and purveying enemy propaganda. He is also said to have remarked that if the Northern Ireland Office had been in control of BBC policy, the IRA would have been defeated. Sir Michael later referred to this encounter as ‘the second battle of Culloden’. Mr. Mason shares the text-book view expressed by the Army’s senior counter-insurgency expert, Brigadier Frank Kitson:

But Kitson adds a warning: ‘The real difficulty lies in the political price which a democratic country pays in order to influence the ways in which its people think.’ The BBC was first in the firing line. Despite pressure from the RUC and the government, in March 1977 the BBC’s ‘Tonight’ programme transmitted Keith Kyle’s interview with Bernard O’Connor, an Enniskillen schoolmaster who alleged ill-treatment by the RUC’s plainclothes interrogators at Castlereagh detention centre. If Northern Ireland is the most sensitive issue in British broadcasting, interrogation techniques are its most sensitive spot. Although under severe attack from Roy Mason and his unnatural but strongest ally in the House of Commons, the Conservative spokesman on Northern Ireland, Airey Neave, who accused the BBC of assisting terrorist recruitment and undermining the police, the BBC stood firm. In a letter to the Times (22.3.77), the Chairman, Sir Michael Swann (no doubt with Culloden in mind) wrote:

Whilst the BBC was having its showdown with Roy Mason, at the beginning of 1977, ITV’s ‘This Week’ was having the odd desultory clash with the IBA and the Northern Ireland Office: the IBA did not like a Provisional Sinn Fein spokesman calling for ‘one last push’ to get the British Out, delivered at the end of a film about the fifth anniversary of Bloody Sunday. The sound was subsequently taken down and the ‘offensive’ sentiments lost in crowd noises and commentary. Because the structures of ITV are vaguer and less rigid than the BBC’s heirarchical pyramid, where decisions are constantly referred upwards, its programme makers have traditionally been more protected against political interference from above. Until recent years and the growing political imperatives that the Northern Irish conflict has placed upon it, the IBA was cautious in wielding its power over news and current affairs. But the Authority, now more powerful and confident with every decision it takes, increasingly tends to arrogate to itself the functions of judge, jury and executioner. If the programme companies, powerful and influential bodies in their own right, disagree with the Authority’s decision, there is no redress. Television journalism is increasingly hampered by restrictions that Fleet Street does not have and would never tolerate. The Sunday Times may decide to publish and be damned - Thames Television cannot. It is the IBA that takes that decision for it. The Authority has always had an impressive panoply of weapons to hand in the form of wide-ranging statutes which give it the power to stop programmes that offend ‘good taste and decency’, are likely to ‘incite to crime and disorder’ or are ‘offensive to public feeling’. But most awesome of all is Section 4 I (f) of the 1973 Broadcasting Act, which makes it incumbent on the Authority to see that ‘due impartiality is preserved in matters of political controversy or matters relating to current public policy’ (my emphasis.) As always, the interpretation and use of these statutes is a personal matter that depends on the predilections of the person at the top. In recent years the tone and style of the Authority has been set by its Chairman, Lady Plowden, who is believed not to favour or encourage investigative television reporting. Add to this a general public antipathy towards Northern Ireland and it is not surprising that the Authority tends to err on the side of caution when faced with controversy. Nor is the Authority, despite its protestations, immune from political pressure. In the end, when the interests of state and the interests of journalism conflict, the odds are that the former will triumph, particularly when the latter may be challenging the ideology which the Authority itself, by its structure, is bound to reflect. There is no statute in the Broadcasting Act that says that the interests of the state must be paramount. There is no need for one. Nor are the pressures from government on the Authority - or from the Authority on its contracting companies - overt: there are no official memoranda saying ‘Thou shalt not...’, rather letters ‘regretting that...’ and suggesting ‘wouldn’t it be better if…’. When it comes to Northern Ireland the pressure is constant. It consists of not just the standard letters of protest from government and opposition to the IBA and the offending contracting company, but personal meetings between the Chairman of the Authority and the Secretary of State and Chief Constable of the RUC. These discussions are confidential, but their results gradually filter down through the broadcasting structures suggesting that more ‘responsible" coverage would be welcome (there is little talk of censorship. Government and broadcasting authorities are usually far too adept and experienced to fall into that trap); that ‘This Week’ might ‘lay off’ Northern Ireland for a while, or that ‘another reporter’ might cover it. And the pressures on the contracting companies are also formidable: in a couple of years’ time the IBA has the power to renew or withdraw their lucrative licences; the second channel, much desired and lobbied for by ITV, is a gift for government to grant or withold. ITV is in the end beholden to both institutions; it takes courage to challenge them. Small wonder then that controversial coverage of Northern Ireland is tolerated rather than encouraged. The problems that ‘This Week’ has faced in the past year illustrate the difficulties confronting journalists attempting to report Northern Ireland as fully and freely as they would a conflict less close to home. The trouble started with ‘In Friendship and Forgiveness’ (August 1977), an alternative diary of the Queen’s visit to Northern Ireland, her last engagement in Jubilee year. The world’s press flocked to Belfast as never before even at the height of the ‘wart in 1972, admittedly more as prospective vultures at the feast, awaiting the Provisionals’ much-vaunted promise to ‘make it a visit to remember’, than as recorders of Her Majesty’s progress through carefully chosen parts of her troublesome province. ITV’s cameras covered the events live. ITN’s senior newscaster declared from the Belfast rooftops that he could almost feel ‘the peace in the air’. For Roy Mason the Royal visit represented a proconsular triumph which the world was there to record. The Provisionals’ threats proved empty: they were humiliated if not defeated. Television brilliantly orchestrated the Royal progress as it had throughout the Jubilee year, but nowhere had its orchestration carried such political overtones which, however lost they might have been on its audience, were certainly not overlooked by the government officials who encouraged it. As a propaganda exercise its success was complete: it presented a picture of a province almost pacified, with grateful and loyal subjects from both sections of the community taking the Queen and her message to their hearts. The reality was different. More than anything, the Royal visit highlighted the political divisions of the province: to Protestants it represented a victory for their tradition which they felt had been under attack for so long, whilst for many Catholics Her Majesty came as the head of a state they refused to recognise. Such was the context in which ‘This Week’ placed its report, filming events that went largely unnoticed and unreported by the army of visiting pressmen - the funerals of a young IRA volunteer shot dead by the army whilst allegedly throwing a petrol bomb and a young soldier shot dead by the Provisionals in retaliation; a Provisional IRA road block in Ballymurphy; a Republican rally in the Falls Road; the Apprentice Boys parade in Derry and an earlier sectarian sing-song; Loyalist street celebrations in the Shankhill; and a four-hour riot - which was widely reported. This potent mixture was intercut with scenes of the Royal progress and interviews with proponents of the two conflicting traditions, John Hume and John Taylor, who placed the visit in its current and historical perspective. The programme, scheduled for transmission a week after the visit, was banned by the IBA. (All ‘This Week’ programmes on Ireland have to be submitted for the Authority’s approval prior to transmission, which is rarely the case with other sensitive issues that ‘This Week’ covers.) The IBA took exception to a section at the beginning of the film in which Andreas O’Callaghan, a Sinn Feinner from Dublin, stirred the crowd at the Falls Road rally with these words:

These words could have been reported by any newspaper journalist but not, apparently, on television. Seeking refuge in Statute 4 (1) of the 1973 Broadcasting Act, the IBA deemed it likely that these words might constitute ‘an incitement to crime’ or ‘lead to disorder’. Thames were advised to seek legal advice. Thames’ counsel concluded:

Significantly he added:

He also pointed out that Section 4 (l)b of the Act requires a news feature to be ‘presented with due accuracy and impartiality’. Accordingly, to play safe and to get the programme on the air, we decided to drop O’Callaghan’s words and replace them with my neutered paraphrase in reported speech:

Counsel felt that we were now in the clear. The IBA decided that we were not. Two minutes before transmission a phone call came from the Authority ordering Thames not to show the programme. A previous film I had made on ‘Drinking and Driving’ was put on in its place. But the O’Callaghan speech was not the only section of the programme that worried the IBA. They were anxious about the Provisional IRA road block in Ballymurphy, which they suspected we had set up. We had not. My commentary made the position clear:

Nevertheless the Authority remained worried that we might be in breach of the Northern Ireland Emergency Provisions (Amendment) Act 1975 by ‘aiding and abetting the offence of wearing a mask or hood in a public place’. Thames’ counsel implied that this was nonsense. Finally, the IBA expressed concern over my final lines of commentary delivered over film of the soldier’s funeral in his Yorkshire mining village:

It was the last sentence that caused the agony. The IBA argued that it presented an ‘incomplete’ picture of the problem, there being no mention of religion, of Catholics and Protestants and the Army keeping them from each other. I argued that to amend the sentence as the Authority requested was a distortion of the essence of my report. After much discussion, my words were allowed to stand. ‘In Friendship and Forgiveness’ was finally transmitted two weeks after the visit, trickling out over the ITV network in slots that ranged from Friday teatime and Sunday lunchtime to nearly midnight on Ulster Television. By then the visit was history, the impact and topicality of the film lost. Significantly, the film finally shown was not materially different from the version banned two minutes before transmission. Was there collusion with government to prevent a mass audience seeing a different version of ‘reality’ presented at peak time, whilst memories of the event were still fresh? What damage would this perspective have done to the cosmetic presentation so carefully served up by the media? One can only guess. One Northern Ireland Office official I spoke to afterwards said he thought the film ‘stank’. We had not planned ‘In Friendship and Forgiveness’ in advance. We had gone to Belfast to prepare a programme that examined conditions in the prisons and the issue of Special Category Status. When we saw the unreported impact of the Royal visit, we changed tack. We then returned to complete the prisons film we had started, ‘Life Behind the Wire’. The programme, which included film secretly shot by the UDA inside the compounds of the Maze prison, showing prisoners parading openly in paramilitary uniform unchallenged by prison officers, highlighted the conflict between the government’s insistence that the prisoners were common criminals lacking political motivation, and the inmates’ view of themselves as political prisoners. Again, the programme was designed to examine the political nature of the conflict in Northern Ireland. The politicians did not like it. (During the research period, the Northern Ireland Office suggested I make a profile of Roy Mason’s first year in office). The prisons, they repeated, were not an issue. They prefer to dictate the issues’ themselves. Airey Neave called for ‘the most immediate action to stop the flow of Irish terrorist propaganda through the British news media’. He protested to the IBA about the ‘myth that the terrorists in Northern Ireland are heroic and honourable soldiers’. Interestingly, Unionist politicians attacked not ‘This Week’, but the government for tolerating such a situation in a British gaol. For their own political reasons, they welcomed our taking the lid off Long Kesh, which Harry West, their leader, referred to as a ‘terrorist Sandhurst’. The government preferred the lid to be kept on. No one questioned the accuracy of the picture we presented. We submitted the film to the IBA. They had no objections, although one of their officials remarked that the political perspective of the film disturbed him. The real outcry came over two weeks after the programme had been transmitted, when the Provisional IRA shot dead Desmond Irvine, the Secretary of the Northern Ireland Prison Officers’ Association, whose remarkable interview was the backbone of the film. Prison Officer Irvine agreed to the interview after long discussions with his colleagues, and decided to do it openly, fully aware of the risks he was taking. The Northern Ireland Office did not wish him to be interviewed. Political critics of the programme, and of ‘This Week’s’ previous coverage, did not hesitate to lay responsibility for his death at our door, despite the public declaration by the Association that they did not blame the programme for P.O. Irvine’s death. Nor was Desmond Irvine displeased with the film or his own contribution to it. A few days before his death, he wrote to me saying:

His death, however unconnected it may have been with the programme, placed another weapon in the hands of ‘This Week’ critics and those who wished to curb or prevent coverage of sensitive corners of Northern Ireland policy and practice. Moral pressure could now be applied even more forcefully not only to the programme makers, but to those to whom they were answerable. ‘Putting lives at risk’ and ‘responsible reporting’ took on a new dimension. These arguments ‘were widely used to try and stop ‘This Week’ from making and transmitting its next film, ‘Inhuman and Degrading Treatment’, an investigation into allegations of ill-treatment by the RUC at Castlereagh interrogation centre. It proved to be the most delicate issue that ‘This Week’ has tackled in Northern Ireland, highly sensitive because it questioned the interrogation techniques that were the cornerstone of the government’s security policy. The undoubted successes that Roy Mason claimed in putting the ‘terrorists behind bars’ were in 80 per cent of cases the direct result of statements elicited -in theory voluntarily - in police custody, on which a suspect could be convicted in the absence of further evidence. For several months in 1977 there had been growing disquiet initially amongst Catholics, eventually amongst Protestants too, concerning the manner in which these statements were being obtained. The allegations of ill-treatment were persistently dismissed by government and RUC as terrorist propaganda, the last cries of defeated and discredited organisations. During our numerous visits to Belfast the allegations grew stronger and more widespread. We had off-the-record discussions with senior figures in the legal field, who expressed growing anxiety at the way in which they believed some confessions were being obtained. They felt that our investigating the issue, within the context of the crisis and the special legal framework designed to cope with it, would be neither irresponsible nor untimely. We examined 10 cases of alleged ill-treatment in the programme. Each case had strong corroborative medical evidence. We asked the RUC for a background briefing and assistance, acutely aware of the dangers of being taken for a ride by the paramilitary organisations whose causes were undoubtedly helped by the propaganda generated by the issue. After lengthy discussions, the RUC refused all cooperation. There were to be no facilities nor, more significantly, any interview with the Chief Constable. The Northern Ireland Office, washing their hands of the problem by saying it was ‘one for the RUC’, were quick to remind me of the death of Desmond Irvine. We pressed ahead. Six days before transmission, we sent a detailed telex to the RUC - without whom the IBA thought the programme incomplete -listing the cases and medical evidence and outlining a script of the programme. Three days later, word came back that there was still to be no interview. No doubt the various hot lines buzzed. The day before transmission, the Chief Constable offered not an interview but an RUC editorial statement to camera. This compromise was unwelcome to the programme makers, but in the end we were forced to accept it. No statement - no programme. The institutions had triumphed again. A few hours before the programme was due to go out, the chief constable put his men on ‘red alert’, publicly declaring that his policemen were being put at risk by a television programme. Nothing happened. The Chief Constable, who invited Lady Plowden to lunch at his Belfast Headquarters, complained to the IBA that the programme was ‘ seriously lacking in balance’. (Whose fault was that?) The Northern Ireland Office issued an unprecedented personal attack on the reporter who had ‘produced three programmes in quick succession which have concentrated on presenting the blackest possible picture of events in Northern Ireland’, pointing out that ‘after the last programme a prison officer was murdered’. Roy Mason accused the programme of being ‘riddled with unsubstantiated conclusions’ and being ‘irresponsible and insensitive’. (Privately, senior legal figures welcomed the programme. They believed it to be accurate and welcome.) Letters of ‘stern and strict’ complaint were dispatched to the IBA and Thames Television, accusing ‘This Week’ of ‘consistently knocking the security forces in Northern Ireland’. A showdown was in the air. It came eight months later a period in which ‘This Week’s’ producer David Elstein was told to ‘lay off Northern Ireland’ - in the form of the Amnesty Report. Amnesty International had sent a mission to Belfast to examine the allegations of ill-treatment a week after ‘This Week’s Castlereagh investigation. The government and RUC announced their intention to give the delegates every assistance, whilst refusing to discuss individual cases. Amnesty was given the facilities ‘This Week’ was denied. Few could argue that their report would be unbalanced or one-sided. In the event, the Amnesty Report was a devastating document. ‘Maltreatment,’ it concluded, ‘has taken place with sufficient frequency to warrant a public enquiry to investigate it.’ The Report was widely leaked ten days before publication. National newspapers reported its contents and the BBC’s ‘Tonight’ programme quoted extensively from it. In the light of the leaks, ‘This Week’ planned a programme to discuss the Report through interviews with the usual Northern Ireland cross-section of people - mainly politicians - each of whom had read a copy of the report with which we had provided them. Over half the interviewees were well known for their staunch support of the RUC. The IBA banned the programme. There was no appeal. The decision was clear-cut. By chance, the 11 members who had constituted the Authority had met that morning and reached a decision, it was argued, which it was impossible to countermand. On what legal grounds the decision was made was not, and still has not been, made clear. The Authority declared that it would be premature to discuss a report ‘until it is public, thereby giving those involved and the general public a chance to study it in detail’. As Enoch Powell commented when told on his arrival at the studio that the programme had been banned: ‘If we did not talk about what was premature, we would not talk about very much!’ There was no invocation of sections of the Broadcasting Act, as in the case of ‘Friendship and Forgiveness’; no discussion of amendments or compromises that might make it more acceptable as in ‘Inhuman and Degrading Treatment’. The fact that the government had issued a ten-page reply to an unpublished report a matter of hours before the planned transmission of the programme, cut no ice with the Authority. The ban was an act of political censorship pure and simple: the pressures which had mounted over the past year at last had the desired effect. The IBA proved unable, perhaps unwilling, to resist them. Not surprisingly, government and the Authority denied political interference. Few believed them. Anthony Smith’s prophesy had been fulfilled four years ahead of its time: the institutional relationships between the broadcasting authorities and the state were now firmly cemented. ITV technicians blacked the screen in protest, a screen that was nevertheless loyally watched by 20 per cent of the London audience! Thames Television publicly attacked the IBA’s decision, and Jeremy Isaacs, the Programme Controller, granted BBC ‘Nationwide’s’ request to transmit sections of the banned programme. Fleet Street rushed to Thames’ defence. The Sunday Times (11.6.78) described the IBA as ‘one of the biggest menaces to free communication now at work in this country’ and stated: ‘Over Northern Ireland a new wave of political pressure is making itself felt.’ The Economist (17.6.78) accused the IBA of ‘an act of violence on free speech’. The Listener (15.6.78) said the Authority should treat the programme companies and the viewers ‘as adults’. Even the Sunday Telegraph (11.6.78) admitted that’ "This Week’s" record in Northern Ireland is pretty deplorable, so is the IBA’s recourse to banning the other night’s edition’. In an apologia in the Sunday Times a week later, Sir Brian Young, Director General of the IBA, limped to the defence of his Authority. He wrote:

What could have been more concerned with individual rights, the truth and the public good than the programme that ‘This Week’ had planned? When the Authority blew the whistle on the Amnesty Report, they were clearly using a set of unwritten rules one side did not recognise. The post mortem continues. The repercussions for the broadcasters have yet to be felt. The years ahead may be even more difficult. No British government is likely to be more tolerant of open reporting of Northern Ireland or less concerned about the politics of information. Events of the past year have made it clearer than ever that in reporting Northern Ireland the independence of broadcasting, as well as lives, is at stake. Peter Taylor Is a Thames Television reporter.

CENSORSHIP AND THE NORTH OF IRELAND

The British Government therefore exercised great pressure at home and abroad to distort the truth, their simple case being that they were honest peacemakers caught in the middle of a savage war between Catholics and Protestants. On the unjust killings of civilians they always got their story to the media -they were fired at first, the civilian was carrying a weapon, pointing a weapon, etc. The British media accepted the Army spokesmen - as did Radio Eireann often. THE BIG LIE was one of the most hurtful things to people who suffered and knew the truth. The British Army version was what the people in charge of the British media wanted themselves; so they would not seek out the truth. Father Denis Faul and I tried to break through on this many times: we had to resort to writing our own pamphlets -on the murders of Leo Norney, Peter Cleary, Majella O’Hare, Brian Stewart, for example. We are at present writing a pamphlet on the 11 men killed by the SAS in the past year. Which of the media has undertaken that? They are guilty by their silence and omission - these are the big sins of the British media. We are convinced that a D notice was served on the British papers at the time of internment and the torture of the Hooded Men in August 1971. The Sunday Times was given statements on the cases of the Hooded Men weeks before they printed it. John Whale then got the scoop of the year - and was honoured as journalist of the year -although this information was available weeks before it was printed. On the question of torture and brutality one could only break through occasionally in the British media (nothing compared to the immense time and orchestration of media for the Peace People). Again one had to resort to one’s own pamphlets - The Hooded Men, British Army and Special Branch RUC Brutalities, The Castlereagh File, The Black and Blue Book. Catholic papers like The Tablet and The Catholic Herald would print little or nothing. The Tablet refused information from me, even though I got a letter of recommendation. The Belfast Telegraph also refused copy on torture. The first time the BBC TV approached Father Denis Faul was six years after the troubles had started - and then for a programme on abortion. He asked them where they were for the last six years. The same is true now on prison conditions. The British media still accept Mason’s lie that the punishments in H Block are self-inflicted (as they accepted that torture was self-inflicted despite Strasbourg and the Amnesty Reports). So we resort to our own publications on the prisons - Whitelaw’s Tribunals, The Flames of Long Kesh, The Iniquity of Internment, H Block. In short only occasionally and at a late stage do the media take an interest in the serious problems of violations of human rights in the north of Ireland. On the rare occasion they do act it is of infinite value - example Keith Kyle’s programme on Bernard O’Connor, ITV’sA Question of Torture, and the recent Nationwide programme on H Block. Truth is a pillar of peace. The media have failed us utterly over ten years. ____________________________

This statement was written for the Theatre Writers’ Union conference on censorship in London on 28 January 1979.

The Northern Ireland Office and the media

The journalist, said the official, was considered ‘irresponsible’ by those who had been trying ‘to keep the peace in Northern Ireland’, and what he wrote was ‘not helpful’ in circumstances where lives were at stake. He was ‘misguided’ and perhaps should be put on other stories.

Three years ago, a Foreign Office official seconded to the Northern Ireland Office in Belfast chaired a seminar for Belfast editors and reporters. They were asked not to state in future the religion of the (mostly Catholic) victims of sectarian assassinations. It suited the NIO strategists at the time for such killings to be presented as part of a mindless campaign of random violence conducted by the enemies of the state. The police in Northern Ireland supported the NIO’s view, and as they are the main source of news about killings there, very few newspapers now carry this relevant detail.

Another example of successful NIO manipulation came with the publication of the 1976 European Commission report concluding that Britain had been guilty of torture in Northern Ireland. The day before the report was to be published, Merlyn Rees, then Northern Ireland secretary, and his officials, called several newspaper and TV editors into his Whitehall offices for drinks and a chat about what was likely to come out in the report. As a result almost every British newspaper carried identical editorial leaders on the day of the report’s publication - leaders which diverted attention away from the guilty verdict and instead suggested that the Irish Government was wrong for raising the issue in the first place. The Daily Express headlined the story, REES LASHES DUBLIN OVER TORTURE REPORT, the Times, ANGRY REES ATTACK AS DUBLIN CHARGE OF TORTURE IS UPHELD: the Daily Telegraph, REES ANGRY AS EIRE PRESSES TORTURE ISSUE, the Sun, TORTURE TURMOIL, BRITAIN LASHES BACK OVER THE GUILTY VERDICT, the Financial Times, IRISH PERSISTANCE ANGERS UK, the Mirror, REES IN STORM OVER TORTURE. Just as the NIO wished, such headlines gave the impression not that Britain was in the dock, but that Ireland was the guilty party. (see the Leveller, June 1978, and Geoffrey Bell in the Journalist October 1976). Pulped - ‘A Society on the Run’ In 1973 Penguin Books published A Society on the Run: A Psychology of Northern Ireland. Written by Rona M. Fields, an American social psychologist, the book was the result of two years of research in Northern Ireland and included a strong condemnation of British interrogation methods. As a result of what Rona Fields calls ‘a massive effort on the part of the governments involved to suppress my findings’, A Society on the Run was first censored, then withdrawn from the British market - and 10,000 copies were shredded. In 1977 an expanded version of Rona Fields’ research, Society Under Siege, was published in the United States by Temple University Press.

Pulped - ‘Observer’ supplement During the summer of 1978, Mary Holland was commissioned to write a feature for the Observer colour supplement to mark the tenth anniversary of the unrest in Derry. The supplement, published separately and well in advance of the main newspaper, arrived on editor-in-chief Conor Cruise O’Brien’s desk. The article, ‘Mary of Derry, and Ten Years of Troubles’, immediately excited his attention, and - despite the fact that the magazine with the article featured on the cover had already been printed - he demanded extensive changes. The article described the changes in Derry through the eyes of a Mary Nelis whom the writer had first met in 1968 - apparently among the changes in the text was the imposition of the phrase ‘Mary Nelis claims’ in front of the sentence: ‘She is not involved with either wing of the IRA.’ Mary Holland heard of the development and attempted to find out the extent of the changes, but was apparently met with a wall of silence. The magazine was pulped at untold cost and the new article, with O’Brien-inspired changes but without Mary Holland’s approval, eventually appeared. (see Hibernia 30.11.78)

THE ARMY, THE PRESS AND THE BOMBING OF McGURK’S BAR On Saturday 4th December 1971 McGurk’s Bar, a Catholic pub in North Queen Street, Belfast, was blown up by a bomb. 15 people were killed. Over five and a half years later, on 1st August 1977, Robert James Campbell, a 42-year-old loyalist from Ligoniel, was charged with the 15 murders. Convicted in 1978, he was given 15 life sentences and a recommended sentence of at least 25 years. The evidence at the time pointed to loyalist responsibility. But the Army, anxious to use the incident for its own propaganda purposes, cooked up a story that it was an IRA ‘own-goal’. The press was strongly affected by the Army’s story. At best, the papers’ reports suggested that who had done the bombing was a complete mystery. At worst, they pointed clearly to the IRA. The flavour of the Army press conference given after the bombing is best conveyed by Times reporter John Cartres, who devoted his entire story to it. Under the headline ‘Blast that killed 15 may have been IRA error’, he wrote:

In order to pin the blame on the IRA, the Army had to discredit two pieces of evidence that pointed strongly to loyalist responsibility. First, a young paper seller said he had seen a car stop outside the pub, and a man getting out of it and planting the bomb. Second, the bombing was followed by an anonymous phone call claiming that the ‘Empire Loyalists’ had done it. The Army got round the paper seller’s evidence by manufacturing contrary ‘evidence’. RUC (or Royal Army Ordnance Corps, depending on your paper) specialists ‘confirmed’, as the Guardian put it, ‘that the device had exploded inside the bar, and not outside as had been thought earlier.’ The Army responded to the loyalist claim by saying they were ‘suspicious’ of the call, but would not rule it out ‘as being a double-bluff by Republican extremists.’

In addition, the army provided ‘proof’ for the theory that the IRA did it by inventing a complex story - loyally reproduced by Chartres - about an IRA plan to bomb a target in the North Queen Street district. The press went to town on the bombing in a manner calculated to cause the maximum confusion in the public mind and to imply that if anyone did it, it was the IRA. ‘WHO DID IT?’ cried the Sun’s front page headline. ‘Security forces have no clue to the mad bombers. Could it have been an accident? Was the bomb left there to change hands, destined to bring havoc somewhere else in Fear City?’ A centre page headline rubbed home the message: ‘WAS IT MURDER BY MISTAKE?’ The Mail’s headline pursued the same theme with ‘Riddle of who planted the bomb that killed 15 in McGurk’s Bar.’ Despite the fact that the Mail’s coverage included a lengthy interview with the young boy who said he had seen the bomb being planted, the Mail refrained from openly pinning the blame on loyalists. The Mirror concentrated on a long description of the bombing under the headline ‘MASSACRE AT McGURK’S BAR’. The report could be described as accurate by default - it mentioned IRA denials, it did not cover the Army’s theories, but neither did it directly blame the loyalists. The Telegraph, as might be expected, repeated the Army’s statements in a somewhat curious report which started with an Army denial that the bomb had been planted by British intelligence agents. The Daily Express led off with the ‘Empire Loyalists’ phone call - but devoted the remainder of its article to the Army theories and omitted to mention the paper-seller’s eyewitness account. It was left to the Guardian to draw out the implications of the bombing and state that ‘Protestant militants’ were the most likely culprits. Simon Winchester started by mentioning that locals were ‘convinced that Protestant extremists were responsible for the outrage’ and went on to mention the paper-seller’s account and the Loyalist phone call. But the effect was muted by the neutral headline, ‘Belfast sorrow turns to anger’, and by the fact that the bulk of the article was concerned with the Army’s theories. So only the dedicated reader would follow the piece through and arrive at his conclusion that the bombing was unlikely to have been done by the IRA, accidentally or otherwise, and that Protestant militants ‘have a reason for committing such an outrage’. In his reporting of this incident John Chartres of the Times had proved himself the Army PR man’s dream, and Simon Winchester was the reverse. But by introducing their cooked-up theory about IRA involvement the Army had set the tone for all the reporting, even Winchester’s. For ‘quality’ journalists cannot afford not to give serious consideration to the views of the authorities.

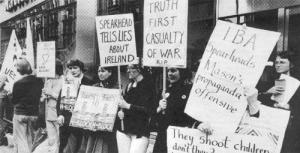

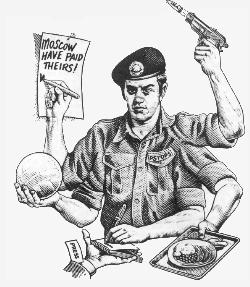

INFORMATION, PROPAGANDA AND THE BRITISH ARMY No organisation likes to appear inefficient and yet a certain insouciant amateurism has always been an important part of the British Army’s self-image. This is particularly apparent in its policy towards information and propaganda. As it is beneath the dignity of an officer and a gentleman to make a fuss on his own behalf, it is only to be expected that the other side will score all the propaganda points. It has become one of the defining characteristics of the British enemy, in cold wars as well as hot, that they should be good at that sort of thing. In Northern Ireland this has taken the form of crediting the Provisional IRA with a skill and competence for propaganda which would not be allowed to other aspects of its operations. If they are clever propagandists it just goes to show: a) that they are rightly identified as the enemy - they don’t know the British way of going about things; b) that anything they or anyone remotely connected with them says cannot be trusted; c) that the army is right to be careful about the information it makes available itself for fear that devious minds on the other side will find a way of turning it to their advantage. The result is both a propaganda victory - to discredit the enemy - and a propaganda policy - to keep it quiet. It is the strength of this tradition which seems to explain what is otherwise a puzzling feature of army practice. In spite of the experience it has built up in fighting a series of rearguard actions in various colonial locations since the Second World War, the army has continually had to relearn the lessons of each of those experiences as it has become involved in a new conflict. Each time it has rediscovered that it is involved in a battle not for lives and territory but ‘hearts and minds’, to use Sir Robert Thompson’s Malayan phrase; each time it has learnt that silence is not sufficient evidence of honourable intentions -actions like Operation Motorman or the Falls Road Curfew speak louder than words - and each time it has painfully reconstructed the machinery necessary to win such a battle. The reconstruction is painful first because it goes against the grain to accept that it is necessary at all - the natural reaction, as expressed vigorously by Roy Mason when he became Secretary of State, is give us some peace and we’ll finish the war; second, because effective propaganda involves time, effort, coordination and centralisation, and third because propaganda is more of an art than a science. There is always the risk that mistakes will be made which can only be seen as mistakes with the benefit of hindsight. A simple ground rule such as that summarised by a senior Information Officer in the question ‘is it good or bad for the army?’ begs a host of further questions about who is making the assessment and what criteria will they use? Standard rubrics of traditional warfare, as for example ‘the only good German is a dead German’, cannot be trusted in a conflict in which a dead Irishman may well turn out to have been a good Irishman. The basic distinction between good and bad - ours and theirs - is missing in a conflict when they cannot be reliably separated from another larger group - the innocent. This is one reason why it is plausible to argue that the other side starts with a propaganda advantage. It also underlines the importance of intelligence in operations of this sort and suggests why it too may turn out to be a double-edged weapon. Given the problems of sorting guilty from innocent, complicated by the fact that there have often been uglies (Ulster loyalists) as well as baddies (IRA) making trouble and that even the baddies divide into different groups, sinister politically-motivated baddies (IRA officials, IRSP, etc.), politically-naive, physical-force baddies (IRA Provisionals) intelligence makes use of quite trivial and indirect evidence to label the enemies. This may be spectacularly successful as in the recognition of the Irish connections of an active service unit in England but it is a blunt instrument, one which makes every Irish person a potential suspect and one which is liable to cause smouldering resentment if not a major scandal when it is institutionalised as in the current Prevention of Terrorism legislation.  A picket of the Independent Broadcasting Authority on 18 July 1978 when ITV began showing the ‘Spearhead’ series. The protestors were drawing attention to the fact that while the IRA has a history of banning programmes that Question British policy in Ireland, it was prepared to sanction a series that was sympathetic to the Army (for further details see Chronology) This act with its provisions allowing some citizens to be excluded from England by the Secretary of State simply on the basis of suspicion and place of birth, without a right of appeal against the grounds for suspicion and with other channels of publicity denied, brings us back to the basic British information policy, secrecy. Sections of the British press and broadcasting can be faulted for the purposive myopia which they have adopted in looking at Northern Ireland, but the problems faced by those journalists who have succeeded in fanning the embers into major or even minor scandals show that it would be unfair to lay the blame entirely at the door of the media. For one thing, the variety of sources and opinions built into the democratic system through parliament and the parties has been lacking in a conflict which has been treated overtly as a matter of bipartisan agreement. Journalistic activity has increased at times when the agreement has been under strain largely because sources close to the Army in the Conservative Party felt the time was opportune to press for a more active security policy. To get the authorisation necessary to license an accusation or opinion in public, journalists have increasingly had to rely on institutions outside the British nation state, the European Court of Human Rights and similar supranational bodies.

Issues raised in this way are licensed in the sense that responsible bodies can be shown to be taking them seriously. In earlier stages of the conflict issues were raised before similar bodies set up by the British state, commissions and committees of various shapes and sizes. The process of widgery in which these engaged to delay and obfuscate the issues demonstrated further the way journalism, to be effective, needs allies within the state apparatus, and these are only forthcoming if there are internal conflicts of interest. For issues to be taken seriously in public, to be licensed as important by some authoritative body, requires evidence about the facts of the case. Whether or not such evidence can be Found, given the fact that oppositional sources are prima facie discredited, depends on the extent to which official sources speak with one voice. This brings us back to the second lesson which the British army has continually had to relearn painfully. Information-giving has been a despised activity, irrelevant to the essential business of soldiering and unlikely to count to the credit of an aspiring officer in his military career. It has taken the army time to develop its own system of press and information officers distributed at all levels of command and to co-ordinate its information activities with those of other ‘official sources’, the police and the Northern Ireland office. Even now there is room for doubt that a 5 day course in ‘basic PR skills’ for serving officers detached to act as Unit Press Officers will change the habits of a career, especially as Press Liaison still appears to be a low status activity. Confronted with the name and rank of the Chief Information Officer at the British Army’s Lisburn HQ, the soldiers on the gate denied all knowledge of the individual and his department and were only slightly less sceptical when shown a letter inviting me to meet him. Inside the officer has a direct line with the commander in chief N.I. and the operations room upstairs but the question remains how much traffic it carries and in which direction. Nevertheless, in so far as such measures of training, coordination and control are effective, they have the effect of cutting out two of the journalist’s greatest assets; first direct access to military sources who are not authorised spokesmen and who may want to depart from the official line in pursuit of some end of their own connected with the internal politics of army careers, resources and unit pride or the external politics of army Interests in preference to those of other official agencies; second the clue from conflicting official accounts that something is not quite right with any of them and further investigation may be worthwhile. The bigger threat which is clearly visible over the horizon is that new information technologies and computerised control may yet eliminate the all-too-human tradition of the British army referred to above. In some future version of ‘The Navy Lark’ the voice which answers a call to ‘British Intelligence’ may not be Jon Pertwee’s dim-witted bureaucrat but an electronic voice computerised to hear all, see all and say one thing. Philip Elliott works at the Centre for Mass Communications Research, University of Leicester.

THE PRESS AND THE PEACE PEOPLE The phenomenon of the peace people has been described by one reporter as ‘a staggering example of news creation’. The bubble has long since burst. If some British people are disappointed with the peace people’s failure to get results, the responsibility must lie with the media. For the sheer volume of coverage and its uncritical nature built up hopes that could never be fulfilled. In 1977 Richard Francis, then BBC Controller for Northern Ireland, said that in the first three months of the peace movement’s existence, its leaders had been interviewed eighteen times by Northern Ireland BBC. But in the whole year from October 1975 to 1976 there were only eighteen interviews with leaders of paramilitary groups. Francis commented, ‘Maybe we have been guilty of under-representing the forces which have had the most profound effect on everyday life in the province.[1] The peace movement started after the three Maguire children died on August 10th 1976. They were killed by a car which was out of control because British soldiers had shot dead the driver, IRA member Danny Lennon. From the first, the media saw only what they wanted to see. While it was arguably irresponsible for the Army to start shooting when there were pedestrians in the vicinity, this side of the incident was quickly forgotten. ‘The three little Maguire children were killed when a gunman’s getaway car crashed into them,’ wrote Will Ellsworth-Jones in the Sunday Times (5.9.76). A Sunday Times leader writer stated, ‘Three small children were run over and killed by a stolen car in which Provisional IRA men were trying to escape after shooting at soldiers' (15.8.76). Mairead Corrigan was described in convenient shorthand as ‘the aunt of the three Maguire children who were killed by a gunman's car in August’ (Daily Mirror 16.9.76) and as ‘an aunt of the three Maguire children who were killed 11 days ago when an IRA man’s car crashed into them’ (Observer 22.8.76). The News of the World captioned a photo of weeping women, ‘Faces of tragedy at the funeral of the three children killed by an IRA getaway car’ (15.8.76).  The press meets the Peace People at their London rally in Trafalgar Square on 27 November 1976 Photo: Andrew Ward/Report Peace movement rally attendances were exaggerated with gay abandon. Fionnuala O’Connor wrote in the Irish Times, ‘Having heard a visiting BBC man argue fiercely one night that anyone less than enthusiastic about the peace women must be a Provo, it was no surprise to hear him next day reckon at 40,000 at a rally on Derry’s Craigavon Bridge. The next bulletin halved the estimate. Most other reports put the crowd below 17,000.’ On the day of their London demonstration on Saturday November 27th the midday edition of the Evening News provided a spectacular example of wishful thinking. On the streets before the marchers even began to assemble, the massive front-page headline read, ‘The Great Peace Guard’, and Bernard Josephs’ article ran, ‘Fifty thousand Ulster peace campaigners were ready to march in London today...’ The next day the estimates came down a bit - though the presentation, with glamorous photos of the leading actors - was still ecstatic. ‘20,000 turn out for peace,’ announced the Sunday Times. The Observer and the Sunday Express had 15,000. It was left to the Irish Sunday Press to provide the more realistic figure of ‘over 10,000.’ Reporters came under pressure from their editors to flatter the peace people, and many were not too happy about it. Sarah Nelson, who researched British press reporting of Northern Ireland for the Richardson Institute for Conflict and Peace Research, writes,

The peace movement had the blessing not only of editors but of the British Government. In September 1976, three weeks after becoming Northern Ireland Secretary, Roy Mason told a press conference at Stormont that the Provisional IRA was ‘reeling.’ The number one factor causing this reversal was, he said, ‘the mass movement for peace indicated by public demonstrations in Ireland and Britain.’ Mason’s approval, plus the fact that the peace people were seen by many as essentially an anti-IRA movement which ignored army violence, guaranteed the erosion of support among the people of the Catholic ghettos. Scepticism had begun to set in just four days after the death of the Maguire children. On 14th August 12-year-old Majella O’Hare was killed by a paratrooper’s bullet while on her way to confession in South Armagh. The peace people failed to attend the 2,000 strong protest march that followed her death. And Catholic anger was increased by the fact that Majella’s death received very little press coverage compared with the deaths of the Maguire children. And what coverage there was repeated the lies put out by army press officers. Thus the Sunday Express reported that Majella ‘was hit by a ricochet from a gunbattle between terrorists and paratroopers’ (15.8.76). The Sunday Times said she ‘was killed in crossfire between a gunman and soldiers.’ Andrew Stephen in the Observer repeated the statement, but was honest enough to attribute it to the army: ‘The Army said later that the girl was caught in crossfire after gunmen had opened up on a foot patrol.’ The tightrope walked by the peace people finally snapped when 13-year-old Brian Stewart was shot in the face by a plastic bullet in the Turf Lodge area of Belfast on October 4th. He died on October 10th. Press coverage was minimal and again influenced by a series of army press statements. Brian Stewart’s mother Kathleen was angered by the way the army initially described Brian as an unfortunate victim, and later as a ‘leading stone-thrower.’ She was bitter, too, that the peace people had not sent the customary mass card after his death. She had attended some of the early peace marches - but never again. When Mairead Corrigan and Betty Williams arrived unannounced at a meeting in Turf Lodge called to protest at Brian’s death, they were attacked by women enraged at their ‘low profile’ on army violence. The press did not respond to the incident by analysing the politics of the peace people. ‘Instead,’ as Eamonn McCann noted in the Sunday World (17.10.76), ‘the Turf Lodge incident was automatically interpreted as just another example of the thuggery of Republicans and the admirable forbearance of the peace people in face of it.’ Thus John Hicks of the Daily Mirror reported on October 12th, under the melodramatic headline, ‘We would die for peace,’ ‘The two battered leaders of Ulster’s peace movement clasped hands in a solemn pact yesterday. ‘Undeterred by a beating from a mob, they swore to battle on for peace.., even at the cost of their lives. ‘Mrs. Williams said they were prepared to face even greater violence - and she was not afraid to die.’ Some papers even alleged that the Provisional IRA had staged the violence - despite the fact that Betty Williams said she thought that the men who took them to safety might have been mobilised by the Provisionals. The Turf Lodge incident was to bring out the contradictions that had been present in the peace people’s stance from the beginning, but which had been ignored by the media. They had attempted to win back lost ground by attending the Turf Lodge meeting, but too late for the people of the Catholic areas. At the same time their attendance at the meeting - and their subsequent statement that army activity in areas like Turf Lodge was provocative and drove people into sympathy with the Provisional IRA - horrified their Loyalist supporters. The peace people tried to mollify the Loyalists by insisting that they did support the security forces, merely deploring their ‘occasional’ breaches of the law. But the damage was done. They could not have it both ways. From this point on their popularity rose only overseas, and doubts began - occasionally - to -surface in the quality press. On January 2nd the following year Andrew Stephen noted in the Observer, ‘It is a telling paradox that both the movement and its leaders receive more recognition the further they are away from the Northern Ireland ghetto where they are viewed with increasing cynicism if not downright detestation.' The tale of the British media’s love affair with the peace people was to have a telling sequel. When they had held their London rally in Trafalgar Square in November 1976 - with the ban on the use of the Square for Irish demonstration purposes temporarily discarded - the occasion was billed in the highest terms, its attendance figures shamelessly exaggerated and its impact everywhere evident in the British news media. Yet when Mairead Corrigan came to the Westminster House of Commons on 9th November 1978, just two years later, the press attendance was four Irish journalists, one Soviet newsman, and one agency reporter. Not a word appeared in the British newspapers the day after, and no pictures either. Why was this so? The Commons conference was hosted by the National Council for Civil Liberties, and had two MPs present. Respectability was in the air, and not the least hint of untoward Republicanism was in evidence. Mairead Corrigan’s message this time was to oppose the Northern Ireland Emergency Provisions Act and the policies Roy Mason was pursuing under that Act. She even stated that the Army/ RUC action in trying to close down the organ of Provisional Sinn Fein in Belfast, Republican News, was an affront to the notion of a free press and should have been loudly opposed by those British newspapers who laid claim to such lofty ideals. In short, Mairead Corrigan was not saying what the British news media had come to expect her to say. She was saying unpopular things. Her words would serve no political purpose this time for the British Government. Notes:

Books Steve Chibnall, Law-and-Order News, Tavistock, London 1977 Phillip Knightley, The First Casualty, Quartet, London 1978 John McGuffin, Internment, ch. 15, Anvil, Ireland 1973 Eamonn McCann, The British Press and Northern Ireland, Northern Ireland Socialist Research Centre, 1971 Philip Schlesinger, Putting ‘reality’ together - BBC News, Constable, London 1978<

British press gloats in the wake of Strasbourg finding, Irish Times 20.1.78 Censorship centre spread, Film & TV Technician, Aug.-Sept. 1978 Censorship centre spread, Socialist Challenge 15.6.78 Curran affairs (minutes of BBC ENCA meeting), Private Eye 15.11.71 Light on Ulster, Economist 1.6.78 No wisdom in hindsight, Leveller April 1978 Screening the news (minutes of EEC ENCA meeting), Leveller Jan. 1978 Television’s redundant censors, Sunday Times editorial 11.6.78 (Sir Brian Young’s answer appeared on 18.6.78) Tonight on Northern Ireland - Sir Charles Curran replies, Listener 17.3.77 Why the Army wants rid of the Brigadier, Time Out 9-15 June 1978

Articles Jay G. Blumler, Ulster on the small screen, New Society 23.12.71 David Blundy, The Army’s secret war in Northern Ireland, Sunday Times 13.3.77 Campaign for Free Speech on Ireland, Small Screen = Smokescreen - response to Annan. CFSI, London 1977 Jonathan Dimbleby (unsigned), The BBC and Northern Ireland, New Statesman 31.12.71 Philip Elliott, Misreporting Ulster, New Society 25.11.76 Philip Elliott, Reporting Northern Ireland, Ethnicity and the Media, UNESCO 1978 Peter Fiddick, Visions of Ulster, Guardian 29.5.78 Richard Francis, The EEC in Northern Ireland, Listener 3.3.77 W. Stephen Gilbert, Dreaming about the troubles, Observer 5.6.77 W. Stephen Gilbert, Why the panic?, Observer 28.8.77 Simon Hoggart, The Army PR men of Northern Ireland, New Society 11.10.73 Mary Holland, Mr. Mason plays it rough, New Statesman, 11.3.77 Mary Holland, After the ball was over, New Statesman, 26.8.77 Keith Kyle, Bernard O’Connor’s story, Listener 10.3.77 John McEntee, interview with Jonathan Dimbleby, Irish Press 12.4.77 Tom McFee, Ulster through a lens, New Statesman 17.3.78 Anne McHardy, How Mason leaned on Thames Television, Guardian 9.6.78 Geoffrey Negus, Do we stand by our code when we are under fire?, Journalist April 1977 Sarah Nelson, Reporting Ulster in the British press, Fortnight Aug. 1977 Jeremy Paxman, Reporting failure in Ulster, Listener 5.10.78 Anthony Smith, Television Coverage of Northern Ireland, Index Vol. 1, No. 2, 1972, reprinted in The Politics of Information, MacMillan 1978 Andrew Stephen, A reporter’s life in Ulster, Observer 29.2.76 Andrew Stephen, Mason wants Ulster news black-outs, Observer 23.1.77

INFORMATION ON IRELAND This pamphlet is published by Information on Ireland, 1 North End Road, London W. 14. If you like it, you can help by taking a number of copies and selling them. We give 1/3 discount on orders of 10 or more copies. Single copies cost 50p plus 15p p&p, 10 copies for £3.40 plus 60p p&p. We would like to produce other pamphlets taking up specific themes on the situation in Ireland. We would appreciate any help: financial contributions would be especially welcome. Orders, enquiries and donations to: Information on Ireland, 1 North End Road, London W.14.

|

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||