The Hurt World: Short Stories of the Troubles, edited by Michael Parker (1995)[Key_Events] Key_Issues] [Conflict_Background] [Literature and the Conflict] The following extract has been contributed by the author and editor, Michael Parker, with the permission of the publishers, The Blackstaff Press. The views expressed in this chapter do not necessarily reflect the views of the members of the CAIN Project. The CAIN Project would welcome other material which meets our guidelines for contributions.  This chapter is taken from the book:

This chapter is taken from the book:

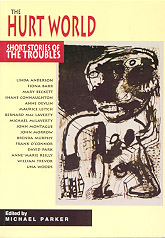

The Hurt World

Orders to local bookshops or:

This publication is copyright Michael Parker (1995) and is included on

the CAIN site by permission of Blackstaff Press and the author. You may not edit, adapt,

or redistribute changed versions of this for other than your personal use

without express written permission. Redistribution for commercial purposes

is not permitted.

From the back cover:

THE HURT WORLD The terror and dislocation of the Northern Ireland Troubles have left a legacy of anger, bewilderment and hurt. But they have also stimulated writing of the highest order: powerful, searching and painfully candid. This timely new anthology of short stories is both a commemoration of that suffering and a celebration of that achievement. In story after story the best writers - Catholic and Protestant, women and men, exiles and natives - explore the stifling pressures of identity and tradition and the brutal impact of violence. Because history can never be safely distant, editor Michael Parker has selected some stories which pre-date 1968, including work by Frank OConnor, Michael McLaverty, John Montague and Mary Beckett, to give a historical context to the brilliance of more contemporary stories by, among others, William Trevor, Anne Devlin, Linda Anderson, Bernard Mac Laverty and Maurice Leitch. An invaluable and moving - contribution to the literature of the Troubles.

THE HURT WORLD SHORT STORIES OF Edited by Michael Parker is Principal Lecturer in English at the University of Central Lancashire and is currently working on Writing the Troubles: Northern Irish Literature and the Imprint of History (Macmillan, 2001), a study of the intersections of literature, history and politics in the period 1958-2000.

Between tall houses down the blackened street; In that bower, closed off from the hurt of the hurt world, T his book is intended both as a celebration and a commemoration. In response to a continuingly dislocating narrative of appalling violence, injustice and suffering over the last twenty-five years, writers from the north of Ireland have struggled to find a language and create forms which might in some way contain their own and a generations horror, anger, grief, and bewilderment. Without the benefit of a bower or retreat to a place out of time (Derek Mahon, Last of the Fire Kings) - for even those who physically left the North did not and could not leave in another sense - these writers have endeavoured to address what Edna Longley has termed the cultural dynamic underlying the conflict, and to fashion in their fictions, with as much integrity and compassion as they could muster, objective correlatives for the brutal experiences endured by ordinary people repeatedly hurt in an uncivil war.Confusion is not an ignoble condition, says Brian Friels schoolmaster at the end of Translations; nor is an acute sense of others and ones own vulnerability. Not surprisingly, these basic human feelings of fear and disorientation manifest themselves within the characterisation and focalisation in the stories, and occasionally, as in the case of Naming the Names, within narrative structures. Frequently, as in Michael McLavertys Pigeons, Shane Connaughtons Beatrice and David Parks Killing a Brit, children are the central characters and focalisers, or, like the narrator of Oranges from Spain, Joe and Colette in Una Woodss The Dark Hole Days, and Finnula in Anne Devlins Naming the Names, young people on the verge of adulthood or in their early twenties, who are forced by their experiences to know again what D.H. Lawrence calls the painful terrified helplessness of childhood, to feel like the young IRA volunteer in Frank OConnors Guests of the Nation, very lost and lonely like a child astray in the snow. Attempts to suppress the memory of pain and the pain of memory inevitably fail, such as when the adult narrative voice at the beginning of Oranges from Spain confesses to the reader that I stopped telling anyone about the nightmares and kept them strictly private. They dont come very often now, but when they do only my wife knows. Sometimes she cradles me in her arms like a child until I fall asleep again. In these stories, and in the ones with older protagonists, such as Mary Becketts A Belfast Woman or William Trevors The Distant Past, the concepts of personal choice and authority have all but disappeared, and one is constantly presented with figures whose lives seem totally determined by others. Significantly, both the unemployed teenagers in Una Woodss novella keep diaries, endeavour to construct their lives into a defining narrative: whereas the young woman envisions the very act of writing as a way of opening up possibilities, asserting her presence in the face of constraining domestic loyalties, Joe uses his text to record his increasing loss of self in a paramilitary fiction, with its myth of a cleansing, liberating violence, which makes him feel part of something, with friends and important thoughts about history and the country. Unlike those people on both sides of the Irish Sea who have implied that there is a single version of the truth and of history, and merely recycled myths about the other side in order to maintain a. solidarity bred on fear and ignorance, the best writers from both traditions have in the main avoided the temptation to massage collective feelings, to use a phrase of Seamus Heaneys. In fact, the Troubles experience has often led to texts in which the writers own communities and their value systems have been subjected to a rigorous scrutiny. The nucleus of John Montagues 1963 story The Cry is an incident in which a Catholic teenage boy is beaten up by four B Specials. However, when Peter, a young Irish journalist, determines to expose the case in the English press, he quickly comes up against fierce opposition from his own people, including the victims family. Peters mother speaks for all of them, perhaps, when she counsels a path of resignation: Theyre a bad lot... But we have to live with them... Why else did God put them there? Although Montague is clearly condemning the gross abuse of power within what Michael Farrell terms the Orange State, his narrative also articulates the frustrations of the younger generation with the pre-civil rights Nationalist Party position, endorsed by the Catholic Church, that it is meet and fitting to suffer silently. Many of the other stories exhibit their female characters increasing impatience with, and resistance to, male readings and patriarchal order, and illustrate the point that Troubles literature - or rather, contemporary Northern Irish writing - is not just concerned with bombs and bullets, but with many other issues of power. The abandoned wife in Mary Becketts The Master and the Bombs makes no bones about the resentment she feels towards her activist husband and the mythic status surrounding those on political charges. An acerbic portrait of male-reverencing bourgeois Protestantism is provided in Linda Andersons The Death of Men, which, to switch metaphors, makes easy meat of its men. The passing-on of one ineffectual patriarch on Christmas Day, only to be upstaged by a turkey, prompts the narrator to recall the death of her own father; another equally joyless and forbidding man, he was only reduced to tenderness by the effects of cancer. It is obviously no accident that the ill-used central character, Liz OPrey, in Bernard Mac Lavertys The Daily Woman, bears the surname she has, along with the bruises. Complementary to these texts in some ways is Anne-Marie Reillys beautifully succinct and ironic tale, Leaving. At first sight the principal target again seems to be male self-centredness, with the narrator perhaps shifting between an echoed restatement of her mothers convictions and her own adult reading of the situation: My father, as usual, was the problem. He was frightened of the responsibility of buying a house. He might have to sacrifice his social life and he wasnt prepared to do that... He had all he wanted, he could not understand her need (my italics). The second half of the story, however, sees the mothers bourgeois social aspirations to move up the road and better herself and her daughters being mocked by external events. Although the narrator struggles to distance herself from her mothers defeat and the lifetime of unfulfilled longing endured by her mothers generation, she recognises that a determination to will a different outcome for herself may not be enough. Sometimes, as Devlins The Way-paver suggests, the risk just has to be taken to separate oneself, to metamorphose, to be a gull or become that stray seal. That male-chained politics will not suffer contradiction is shown, for example, in Fiona Barrs The Wall-reader and in Brenda Murphys ironically titled A Social Call. The latter story questions macho republicanism, and its system of justice, and asks how the beating of women and the kneecapping of sixteen-year-olds furthers the Cause. Barrs story similarly centres upon the experience of a young mother and wife. An intrigued reader of Belfast graffiti, trapped in routine, she longs for a script which would provide evidence she was having impact on others,. Just as in the grimmest fairy tales, wishes have a way of rebounding on the wishers. The Wall-reader warns of the consequences of talking to strangers, and what can happen to your house if you talk to the Beast. Within much of the collection there is an underlying dismay at the way competing ideologies - republican, loyalist and British - construct the enemy, and a common abhorrence when individual human beings are translated into legitimate targets. One might cite characterisations such as the paramilitary snatch squad in Bernard Mac Lavertys Walking the Dog who are driving around the streets seeking out somebody from the other persuasion in order to make them any body, or Corporal Jessop in Maurice Leitchs Green Roads, whose loathing and self-loathing are triggered on hearing a soft Irish accent while on leave in a Swindon pub; he waits in the car park until the unoffending man leaves, in order to give him a comprehensive beating, for the corporal had been trained to inflict the utmost damage as speedily and as effectively as possible. In An Irish Answer, written for the Guardian, on 16 July 1994, Ronan Bennett has claimed: The conflict is too insistent to be kept entirely out of the arts, but when it enters it tends to be neutral, apolitical, disengaged... In other words the mainstream artistic mediators of the conflict have tended to opt, like the largely middle-class audience they serve, for an apolitical vision. Theirs is the culture of aloofness, of being above it all, of distance from the two sets of proletarian tribes fighting out their bloody atavistic war... Speculation on the causes of the conflict is territory most novelists resolutely refuse to cross. However, the evidence of my reading for this collection and more broadly into Northern literature does not bear out Bennetts charges. Serious writers from the North have not in fact been apolitical, or shirked from showing the injustices and incomprehensions which gave rise to and sustained the violence. When at the opening of A Belfast Woman the main character opens an envelope containing the message Get out or well burn you out, it immediately sets in motion two earlier narratives, as she recalls similar texts from previous pogrom years, 1921 and 1935. The web in Anne Devlins Naming the Names, similarly, is made up of interlinking threads of fictional and real life experiences; symbolic episodes such as Finnulas recurring nightmare about an old woman - Cathleen ni Houlihan, one presumes - who grasped my hand and.., would not let me go, merge with actual historical events such as the burning out of Conway Street and other Catholic streets in Belfast and the arrival of British troops in 1969, and the disastrous introduction of internment in August 1971. (A "terrorist", notes Edna Longley in The Living Stream, is no psychopathic aberration, but produced by the codes, curriculum and pathology of a whole community - and also of an unwhole state, I would suggest.) The institutionalised discrimination of successive Stormont governments from 1922 to 1969 against Catholics is reflected in the patronising attitude of the judges son towards Finnula in the same story and within the predatory character of Mr Henderson in Bernard Mac Lavertys The Daily Woman. A future lord mayor of Belfast, or so he thinks, in public he talks about building bridges between the communities; in private, however, he repeatedly propositions his Catholic cleaning lady. When she finally submits, he speaks to her as if she wasnt there, inspects her, curious as her Creator, fascinated by her bruises. . . praised her thinness, her each rib. A reminder, if it were needed, that injustice and prejudice are not confined to one state or religious affiliation comes in the person of the father in Shane Connaughtons Beatrice and in the fate of the ageing eccentric couple in William Trevors The Distant Past. The Middletons, a brother and sister, are Protestant casualties of the border, marooned in the Republic, holding on instinctively to a house and a history which ceased to afford protection. With the onset of the latest Troubles and the consequent decline in trade and tourism, almost overnight the tolerance of decades ebbs away; the pair are boycotted by their Catholic neighbours, fixed in an equation, left to face the silence that would sourly thicken as their own two deaths came closer and death increased in another part of their island. In Ireland, as in any other colonised or newly independent country, narratives about the past defy closure, and history can never be safely distant; hence the inclusion in this collection of four stories which pre-date 1968 in their composition, Guests of the Nation, Pigeons, The Cry, and The Master and the Bombs, and of stories written from outside the old divisions of Ulster. The polarisation in politics in the North over the past twenty-five years has placed such enormous pressure on individuals within communities to keep faith with the collective historical experience, and on writers to bear witness, that at times the fact has been obscured that they possess not just one single homogeneous cultural tradition, but rather a much more complex, multiple cultural and linguistic heritage. A dramatically broken history, in the words of Seamus Deane, may have left artists caught between identities (The Artist and the Troubles, Ireland and the Arts), but has also established opportunities to scrutinise the ambivalences within origins - those hurled stones, that hurt-instinct - and in the process to employ a diverse range of cultural and historical perspectives, aesthetic strategies. What has been achieved individually and collectively, as these stories I hope demonstrate, has been an art that constantly changes the perceptual angle (Edna Longley) within texts, between texts, within and between people. MICHAEL PARKER

|

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||