CAIN Web Service

CAIN Web Service

Ardoyne: The Untold Truth - Introduction

Ardoyne Commemoration Project (2002)

[CAIN_Home]

[Key_Events]

[KEY_ISSUES]

[Conflict_Background]

VICTIMS:

[Menu]

[Main_Pages]

ARDOYNE:

[Contents]

[Introduction]

[Testimonies]

[Conclusion]

[Report]

Text: Ardoyne Commemoration Project ... Page Compiled: Brendan Lynn

The following chapter (and additional extracts) has been contributed by the authors, the Ardoyne Commemoration Project, with the permission of the publisher, Beyond the Pale. The views expressed in this chapter do not necessarily reflect the views of the members of the CAIN Project. The CAIN Project would welcome other material which meets our guidelines for contributions.

This chapter (and additional extracts) is taken from the book:

This chapter (and additional extracts) is taken from the book:

ARDOYNE: THE UNTOLD TRUTH

by the Ardoyne Commemoration Project (2002)

ISBN: 1-900960-17-6 (Paperback) 543pp

Orders to:

Local bookshops, or

-

Beyond the Pale Publications

[Publisher no longer exists]

Unit 2.1.2Conway Mill5-7 Conway StreetBelfastBT13 2DETel: +44 (0)28 9043 8630Email: office@btpale.com

This chapter (and additional extracts) is copyright the Ardoyne Commemoration Project and is included on the CAIN site by permission of the authors and publisher. You may not edit, adapt, or redistribute changed versions of this for other than your personal use without the express permission of the author. Redistribution for commercial purposes is not permitted.

Rear Cover

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

List of those killed

Preface

Introduction

1. 1969—70

‘Ardoyne will not burn...’

2. 1971—73

‘Hot and heavy’: The War Begins

3. 1974—76

‘Murder Mile’: Truces and Terror Campaigns

4. 1976—84

‘The Long War’: Containment, Criminalisation and Resistance

5. 1985—94

Counter-insurgency, Collusion and the Search for Peace:

From the Anglo-Irish Agreement to the Ceasefires

6. 1994—2002

To the Good Friday Agreement and Beyond

7. Conclusion

Select bibliography

Dedication

To all those who contributed to the book and who have since died:

Jimmy Barrett

Rose Craig

Tom Largey

Mickey Lagan

Patrick McBride

Agnes Mulvenna

Bobby Reid

Rose-Ann Stitt

Acknowledgements

Ardoyne Commemoration Project Committee

Tom Holland (Chairperson, co-editor and interviewer)

Patricia Lundy (co-editor, co-author and interviewer)

Mark McGovern (co-editor, co-author and interviewer)

Phil McTaggart (interviewer and treasurer)

Kelley McTaggart (transcribing)

Helen McLarnon (transcribing)

Additional help and support was provided by:

Mary Brady, Mickey Liggett, Ann Stewart, Geraldine Bmwn, Barry McCafferzy,

Mark Thompson, Jim Gibney, Sean Mag Uidhir, Maria Williams,

Margaret McClenaghan, Kate Lagan, Claire Hackett, Mairead Gilmartin,

Jacqueline Monahan, Dolores Hughes, Marie Murphy, Sam McLarnon, Uschi Grandel

Mike Tomlinson, Agnieszka Martynowicz and Bill Rolston.

The ACP would also like to thank the following groups and organisations:

The Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust, Belfast Regeneration Office (North Team),

Northern Ireland Voluntary Trust, Community Relations Council,

The Lottery Charities Board, The Hans Bloeckler Foundation (Germany),

Ardoyne Fleadh Cheoil, Amach agus Isteach, North Belfast News,

Survivors of Trauma, Edge Hill College, Ormskirk

List of those killed

1969

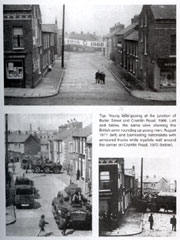

Sammy McLarnon — Killed by the RUC, Herbert Street, 15 August 1969

Michael Lynch — Killed by the RUC, Butler Street, 15 August 1969

1971

Barney Watt — Killed by the British army, Chatham Street, 5 February 1971

Sarah Worthington — Killed by the British army, Velsheda Park, 9 August 1971

Paddy McAdorey — Killed on active service by the British army, Jamaica Street, 9 August 1971

John Laverty — Killed by the British army, Ballymurphy, 11 August 1971

Michael McLarnon — Killed by the British army, Etna Drive, 28 October 1971

Johnny Copeland — Killed by the British army, Strathroy Park, 30 October 1971

Joseph Parker — Killed by the British army, Toby’s Hall, 12 December 1971

Margaret McCorry — Killed by the IRA, Crumlin Road, 20 December 1971

Gerard McDade — Killed on active service by the British army, Brompton Park entry, 21 December 1971

1972

Charles McCann — Killed on active service, Lough Neagh, 5 February 1972

Bernard Rice — Killed by loyalists, Crumlin Road, 8 February 1972

David McAuley — Died as a result of ‘accidental discharge’ from an IRA weapon, Fairfield Street, 19 February 1972

James O’Hanlon — Killed by the IRA, Gracehill Street, 16 March 1972

Sean McConville — Killed by the UDA/UFF, Crumlin Road, 15 April 1972

Joseph Campbell — Killed by the British army, Eskdale Gardens, 11 June 1972

Terry Toolan — Killed on active service by the British army, Eskdale Gardens, 14 July 1972

James Reid — Killed on active service by (persons unknown), Eskdale Gardens, 14 July 1972

Joseph (Giuseppe Antonio) Rosato — Killed by (unknown), Deerpark Road, 21 July 1972

Patrick O’Neill — Killed by loyalists, Forthriver Drive, 22 July 1972

Charles McNeill — Killed by (unknown), Brompton Park, 14 August 1972

Joseph McComiskey — Killed on active service by the British army, Flax Street, 20 September 1972

Gerry Gearon - Killed by the UFF, Crumlin Road, 30 November 1972

Bernard Fox — Killed on active service by the British army, Brompton Park, 4 December 1972

Hugh Martin - Killed by the UVF, outside the Tip-Top bakery, East Belfast, 30 December 1972

1973

Elizabeth McGregor - Killed by the British army, Highbury Gardens, 12 January 1973

Pat Crossan — Killed by the UVF Woodvale Road, 2 March 1973

David Glennon — Killed by loyalists, Summer Street, 7 March 1973

Eddie Sharpe — Killed by the British army in Cranbrook Gardens, 12 March 1973

Pat McCabe — Killed on active service by the British army, Holmdene Gardens, 27March 1973

Anthony McDowell — Killed by the British army, Etna Drive, 19 April 1973

Sean McKee — Killed on active service by the British army, Fairfield Street, 18 May 1973

1974

Terry McCafferty — Killed by loyalists, Rush Park estate, 31 January 1974

Martha Lavery — Killed by the British army, Jamaica Street, 5 August 1974

Thomas Braniff— Killed by loyalists, Sunflower Bar, Corporation Street, 16 July 1974

Albert Lutton — Killed by loyalists in the Ballyduff estate, 10 October 1974

Ciaran Murphy — Killed by loyalists, Hightown Road, 13 October 1974

James McDade — Killed on active service, Salt Lane, Greyfriars, Coventry, 14 November 1974

1975

Thomas Robinson — Killed by loyalists, Etna Drive, 5 April 1975

Francis Bradley — Killed by loyalists, Corporation Street, 19 June 1975

John Finlay — Killed by loyalists, Brougham Street, 21 August 1975

William Daniels — Killed by the UVF, Glenbank Place, 22 August 1975

Thomas Murphy — Killed by loyalists, Antrim Road, 2 October 1975

Seamus McCusker- Killed by ‘Official’ IRA, New Lodge Road, 31 October 1975

Francis Crossan — Killed by loyalists, Shankill Road, 25 November 1975

Christine Hughes - Killed by the IRA in Mountainview Parade, 21 December 1975

1976

Ted McQuaid - Killed by loyalists, Cliftonville Road, 10 January 1976

Paul McNally — Killed by loyalists, Brompton Park, 7 June 1976

Patrick Meehan — Killed by loyalists, Crumlin Road, 17 June 1976

Gerard Stitt — Killed by loyalists, Cninilin Road, 17 June 1976

Paul Marlow — Killed on active service, Onneau Road Gasworks, 16 October 1976

Charles Corbett — Killed by loyalists, Leggan Street, 30 October 1976

John Maguire - Killed by the UVF in Glenbank Place, 30 October 1976

Geraldine McKeown — Killed by loyalists in Mountainview Gardens, 8 December 1976

John Savage — Killed by the British army, Springfield Road, 18 December 1976

1977

John Lee — Killed by IRA, Baihoim Drive, 27 February 1977

Danny Carville - Killed by the UDA, Cambrai Street, 17 March 1977

Trevor McKibbin - Killed on active service by the British army, Flax Street, 17 April 1977

Sean Campbell - Killed by the UVF, Etna Drive, 20 April 1977

Sean McBride — Killed by the UVF, Etna Drive, 21 April 1977

Trevor McNulty — Killed by the IRA, Alexander Flats, 27 July 1977

1978

Dennis (Dinny) Brown — Killed on active service by the British army, Ballysillan Road, 21 June 1978

Jim Mulvenna — Killed on active service by the British army, Ballysillan Road, 21 June 1978

Jackie Mailey - Killed on active service by the British army, Ballysillan Road, 21 June 1978

1979

Frankie Donnelly — Killed on active service, Northwick Drive, 5 January 1979

Lawrence Montgomery — Killed on active service, Northwick Drive, 5 January 1979

1980

Alex Reid — Killed by loyalists, Shankill Road, 3 January 1980

Colette Meek — Killed by the IRA, Alliance Avenue, 17 August 1980

1981

Maurice Gilvary — Killed by the IRA, near Jonesboro, S. Armagh, 19 January 1981

Paul Blake — Killed by the UFF, Berwick Road, 27 March 1981

Patsy Martin — Killed by loyalists, Abbeydale Parade, 16 May 1981

Danny Barrett — Killed by the British army, Havana Court, 9 July 1981

Anthony Braniff — Killed by the IRA, Odessa Street, 27 September 1981

Larry Kennedy — Killed by the UDA/UFF, Shamrock Club, Flax Street, 8 October 1981

Bobby Ewing - Killed by the UFF, Deerpark Road, 12 October 1981

1983

Trevor Close — Killed by loyalists, Cliftonville Road, 26 May 1983

1984

Harry Muldoon — Killed by the UVF, Mouniainview Drive, 31 October 1984

1986

Colm McCaIlan — Killed by loyalists, Millview Court, 14 July 1986

Raymond Mooney — Killed by loyalists, Holy Cross chapel, 16 September 1986

1987

Larry Marley — Killed by the UVF Havana Gardens, 2 April 1987

Eddie Campbell — Killed by loyalists, Horseshoe Bend, 3 July 1987

Thomas McAuley — Killed by loyalists, Crumlin Road, 16 November 1987

1988

Paul McBride — Killed by the UVF, Avenue Bar, Union Street, 15 May 1988

Seamus Morris — Killed by loyalists, Etna Drive, 8 August 1988

1989

Davy Braniff — Killed by loyalists, Alliance Avenue, 19 March 1989

Paddy McKenna — Killed by loyalists Crumlin Road, 2 September 1989

1991

Gerard Burns — Killed by the INLA, New Bamsley Park, West Belfast, 29 June 1991

Hugh Magee — Killed by loyalists, Rosapenna Street, 10 October 1991

1992

Liam McCartan — Killed by the UFF, Alliance Avenue, 12 March 1992

Isabel Leyland — Killed by the IRA, Flax Street, 21 August 1992

Martin Lavery — Killed by loyalists, Crumlin Road, 20 December 1992

1993

Alan Lundy — Killed by loyalists, Andersonstown, 1 May 1993

Sean Hughes — Killed by the UFF, Falls Road, 7 September 1993

Thomas Begley — Killed on active service, Shankill Road, 23 October 1993

1994

Martin Bradley — Killed by loyalists, Crumlin Road, 12 May 1994

1996

John Fennell — Killed by the INLA, Bundoran, 6 March 1996

Fra Shannon — Killed by the INLA, Turf Lodge, 9 June 1996

1998

Brian Service — Killed by loyalists, Alliance Avenue, 31 October 1998

Introduction

‘To give testimony is to bear witness; it is to tell the unofficial story, to construct a history of people, of individual lives, a history not of those in power, but by those confronted by power, and becoming empowered.’ (Perks and Thomson, 1998)

This book tells the story of 99 ordinary people, living ordinary lives, who became victims of political violence in a small close-knit, working class, nationalist community in North Belfast. The deaths occurred between 1969 and 1998 and the victims were from Ardoyne. Because of the ongoing nature of the conflict, victims’ names and the traumatic circumstances of their death were often forgotten or overshadowed by further tragedy and loss. Most of the people who have given testimony in this book are the relatives, neighbours and friends of the 99 victims. Almost all have never spoken publicly about the death of their loved one and the personal costs to their family, friends and community. Their very moving accounts of loss and pain have up until now been private, unspoken and ‘silenced’. To recall such traumatic memories was an emotional and sometimes difficult process for individuals and families to undertake. Until now no one has taken the time to listen to these voices and record their memories of the past. There is evidence from countries emerging from conflict around the world that public recognition of such loss and human rights abuse can provide a cathartic experience for many victims’ families. It is clear from our own discussions with victims’ relatives that it was important for them to be given the opportunity to ‘tell their story’, in their own words without constraints or censorship. What is more, to document such experiences prevents history from being lost, rewritten or misrepresented. It opens the possibility for a society to learn from its past.

What is also apparent from the testimonies is the number of relatives who have never been told ‘the truth’ about the death of their loved one. Many of these testimonies speak of the brutality of a system that treated ordinary people with utter contempt and colluded to ensure lack of disclosure, accountability and justice. Others recall, and have since learnt, personal details that were lost in the pandemonium and confusion that followed such traumatic events. These very vivid and personal accounts tell the ‘hidden’ story of powerlessness, marginalisation and resistance. To compound personal and collective grief, sections of the media have intruded, misrepresented events and given less than equal recognition to all victims. Over the years they have demonised and labelled Ardoyne a ‘terrorist community’, thus implying, in some distorted way, that the community got what it deserved. To add insult to injury, a growing number of books on ‘the Troubles’ have published details about victims’, often incorrectly and without consent, causing further distress to relatives. What distinguishes this book from others is the painstaking effort by the Ardoyne Commemoration Project (ACP) to ensure all participants were given space and time to speak about their experiences, in order to capture the essence of their loved one. Another important feature was that participants were given complete editorial authority over the final draft. This was a huge and time-consuming process given that over 300 people were eventually interviewed. It also explains why the process took almost four years to complete.

In short, this book has sought to give control and ownership over what is written about victims to their relatives and friends. It is primarily a community project and one defined by the importance of writing ‘history from below’. The book offers a platform for the community to ‘write back’ and set the record straight. It puts a human face on statistics, contextualises the deaths in terms of historical events and gives social recognition to the victims of the conflict. It is a collective memory of the community, researched and written by members of that community. The testimonies describe unspeakable loss and pain. It means that this book makes neither easy nor comfortable reading, but given its subject matter, this cannot and should not be. We are, though, deeply conscious that many readers may find these pages difficult and harrowing. The story can feel unrelenting. For some people, too, it may stir up traumatic memories of their own. Such experiences will reflect something of the impact that the project has had on all those involved. Yet, the testimonies also describe resistance and survival in the face of adversity. This has also shaped the experience of being part of the ACP. It is one reason that the members of the project feel a deep sense of gratitude to every person that agreed to be interviewed. The willingness of interviewees to talk about deeply personal and often disturbing memories can only be admired, and only their courage in speaking made this book possible. The project’s aim is to ensure that these unheard voices of ordinary people will enter the public discourse. In doing so they will reclaim an important part of their history for future generations. Who better to tell that story than those who have experienced political violence first hand? If the history of the conflict is to be written well, we believe these very powerful and poignant testimonies can, and must, be allowed to speak for themselves.

The following sections explain the concept, practical stages and processes, methodology and structure of the book. It is hoped that other communities intending to embark on a similar project will find the following practical information useful and the lessons we have learnt helpful.

Why a book?

The concept for the book came about as a result of informal discussions between victims’ relatives, concerned individuals and members of community groups. The political conditions produced by the cease-fires and the Good Friday Agreement created the space for people to begin to reflect upon and discuss the past thirty years of political conflict. As part of that process there has been a period of reflection and reassessment at the individual and community level, in both the private and public sphere. The sense of loss produced by so many deaths, injuries and the various other costs of the conflict created a growing focus on how to deal with the legacy of the past. In Ardoyne people were beginning to reflect upon and discuss these highly contentious issues in what were essentially uncharted waters.

At the same time, in the political aftermath of the Good Friday Agreement, the ‘victims agenda’ came to the fore. As part of the Agreement an early release scheme for political prisoners was announced. Unionist anti-agreement groups and parties seized upon this aspect of the Agreement and linked the ‘victims agenda’ and prisoner releases for political purposes to oppose the Good Friday Agreement. The unionist anti-agreement lobby argued that political prisoners should not be given early release. At the same time they sought to differentiate between victims and to imply that such a ‘hierarchy of victimhood’ should guide public debate and policy on the issue. The British Secretary of State had already established a Victims Commission in October 1997, with Sir Kenneth Bloomfield at its head. Following the publication of the Bloomfield Report (We Will Remember Them) in late 1998, a Victims Liaison Unit was set up and Adam Ingram was appointed as the Minister for Victims. It is through this framework that the government has pursued its response to the victims issue. In themselves, many nationalists regarded the appointments of both Sir Kenneth Bloomfield and Adam Ingram to their respective positions as particularly insensitive. The former had been a long-serving senior civil servant in the Northern Ireland Office, whilst the latter was also in post as the Minister for Armed Forces. With such backgrounds both were seen as lacking impartiality and were viewed as unlikely to be neutral custodians of the needs of all victims of the conflict. The Bloomfield Report was also criticised for having established an exclusive and hierarchical approach to the victims’ agenda, with an implicit suggestion that there were more deserving, and less (if not un-) deserving victims. The ‘undeserving’ victims were inevitably nationalists and republicans killed by British security forces and their agents. Whilst Bloomfield suggested that there should be no such thing as ‘guilt by association’ many of those involved with the relatives of nationalist/republican victims have argued that is precisely the perception which was fostered. The sense has been that, although the Good Friday Agreement was supposed to herald a new era of equality, the Bloomfield Report sowed anew the old seeds of ostracism.

The ‘hierarchy of victims’ and the distinction made increasingly by anti-agreement unionists and others between ‘innocent’ and ‘non-innocent’ victims angered many in the Ardoyne community. To them it seemed as though the anti-agreement unionists had become self-appointed advocates for all victims of the conflict — the supposed ‘legitimate’ voice for victims. Many victims’ families felt that they were at the bottom of this hierarchy, or that they and their lost loved ones were not regarded as victims at all. Their sense of injustice was heightened by the fact that those in the British security forces responsible for many deaths in Ardoyne had never been arrested, interrogated or served time in prison.

It was against this backdrop that in July 1996 a number of victims’ relatives, concerned individuals and representatives from community groups called a meeting to discuss the ‘victims agenda’ and to explore ways in which the community could commemorate their own victims of the conflict; in their own way. No concrete decision was reached at the initial meeting. The general consensus was that something should be done to record the experiences of ordinary people in Ardoyne during the past thirty years of conflict and to mark the sense of loss produced by so many deaths. It was clear from the meeting that people felt angry. They wanted an opportunity to ‘set the record straight’, to ‘tell their story’ from the community’s perspective. After several further meetings, much discussion and debate, the idea of a commemoration book emerged. The Ardoyne Commemoration Project was born and a committee was elected.

The general view was that a book offered the best way to challenge the ‘hierarchy of victims’ agenda and provided the means for the community to tell its own story. It was important to the integrity of the project that the community, as opposed to someone ‘outside’ of the community, should undertake the work. Community participation has therefore been a defining feature of the project, guiding and shaping the project’s development over the past four years. During all stages of the project the ACP made every effort to seek the views and opinions of the participants and the wider community. This process has meant that right from the start the community in effect took ‘ownership’ and control of the design, research process, editing, return phase and production of the book. This makes the project, and the book, unique. This wait is the outcome of ordinary people taking charge of their history, rather than being objects in someone else’s study. The people who have given their testimonies, along with those who have listened, recorded, and edited them, are from within or have strong links with the Ardoyne community. In retrospect the complexity of researching and writing a book was totally underestimated and with the best will in the world naïvely misjudged. At this stage none of us appreciated the extent of the task, the toll it would take on individuals both giving and receiving testimonies and the number of years it would take to complete. As well as the practical problems to be dealt with, those involved in the project had to grapple with a wide range of difficult issues that often took much soul-searching in what was unforeseen terrain for us all.

Defining Victims

One of the first issues that arose at the start of the project was establishing what victims were to be included in the book. This initially seemed straightforward but in reality a number of unforeseen, complex and far from uncontentious issues soon emerged. Even though Ardoyne is an overwhelmingly nationalist/republican community, there exists within it a diversity of groups, opinions and politics. The aim of the ACP was to be inclusive and not to alienate any particular individual, family or group. At the outset the ACP discussed and debated the issue of who should be included in the study and consulted widely with relatives and interested groups who had, up until that point, not participated directly in the ACR After this process of broad consultation, and much reflection (which was a learning process for all of us), it was agreed that the research project should focus on all those victims who, at some point in their lives, had been Ardoyne residents, irrespective of who killed them. There were a number of reasons as to why this specific focus was arrived at, although it was never intended to imply that the suffering of other victims’ relatives and communities is any less worthy of note. The view of the ACP is that everyone’s grief should be respected, that all victims are equal and that no one has a monopoly on grief and loss. What is more, the ACP was highly sensitive to the potential problem of creating an alternative ‘hierarchy of victims’, between and within particular communities.

A major reason for restricting the research to Ardoyne residents was essentially bound up with the manageability of the project. The ACP was a small group of volunteers with limited resources at its disposal. By way of contrast to many other works dealing with the stories of victims and their families a decision was taken early on that substantial time and space needed to be given to each individual story. This was so that their lives, as well as their deaths, could be described. By seeing those who had been killed through the eyes of those who knew them best, the aim was to reveal the human face so often lost amid the welter of statistics, supposedly ‘objective’ historical accounts and media misrepresentations. Such a task presented huge logistical problems that demanded defining a very specific constituency, given the dimensions of the conflict. Of the roughly 3,630 conflict fatalities that have resulted from the war in Ireland during the last three decades almost half occurred in Belfast. Just under 550 deaths occurred in the north of the city alone. Most of these (some 396) were civilians, and the majority of civilian casualties in North Belfast were from the nationalist community.1 The decision to focus on the residents of Ardoyne was, in part, the result of these realities.

Yet even if only those killed in and around Ardoyne were to be considered, issues not only of scale but also of contact and access soon became all too apparent. Of its nature the project was dealing with deeply traumatic and often highly sensitive matters. As a result it was imperative to provide those giving testimonies with a sufficient sense of comfort and ease to speak openly and freely about their experiences. However, the conflict has left a legacy of doubt, fear and suspicion of strangers in places like North Belfast, not least because of the 'dirty war’ carried out there by the state’s intelligence agencies. One of the key strengths of the ACP was that those who conducted the interviews were from the district itself, people who were trusted because of their community, family and friendship ties. That the project was very much rooted in Ardoyne was not only useful, it was essential. Quite simply, these stories could not have been told unless those being interviewed were talking to someone they could place. Only this could offset the old (and often all too necessary adage): ‘whatever you say, say nothing’. However, given the divided geography of North Belfast and the inevitable limits of inter-communal contact engendered by years of conflict, that very ‘rootedness’ precluded easy access to other areas, other (mainly non-nationalist) communities and, as a consequence, other people’s stories. The ‘rootedness’ of the ACP was, in other words, both a prerequisite for the project and an important factor in defining its inevitable limits.

Given this context, the decision taken early on by the ACP, that they would deal with the cases of all those Ardoyne residents who had been killed, was of the utmost importance. In spite of the difficulties of access it ensured that, within the limits set, no victim would be excluded because of their religious or political beliefs, the circumstances of their death, or the agency responsible for it. This reflected the ethos that defined the raison d’être of the ACP; the equality of all victims. Ardoyne is a community that has known its history to be hidden and humanity denied. That is why there has been such a need for its story to be told. But in telling its own story there has been no desire to imply that others should be left untold, or that any death is unimportant. Given its constituency the Ardoyne story is inevitably dominated by victims from particular backgrounds. However, amongst the names of the 99 victims there can be found those of Catholics and Protestants, nationalists and non-nationalists, civilians and combatants, those killed by the RUC, the British army, loyalist paramilitaries and Irish republicans. This remit raised all manner of difficulties, but it was a decision driven by the desire to challenge the ‘hierarchy of victimhood’.

Whilst lying outside the focus of the book it is also important to recognise and acknowledge the wider context of human costs and sense of loss that were the outcome of three decades of war. As well as the 99 Ardoyne residents killed during the conflict there were other civilians (both nationalist and unionist), members of the state security forces (the British army, RUC, UDR) and combatants who died within or on the fringes of the district. It is difficult to establish definitive figures for all such victims and what is outlined below is merely by way of illustration. Certainly there were several nationalist civilians and IRA members from other parts of the North killed within the district. There were also at least a dozen civilians from unionist areas who were killed in the streets that lie within or are immediately adjacent to Ardoyne. Many of these, and the far larger number of victims who died in other parts of North Belfast, were killed (in a very wide range of circumstances) by Irish nationalists and republicans, some of whom came from Ardoyne. An unknown number of loyalist paramilitaries were also killed by people from Ardoyne. Unsurprisingly most of these took place outside the district’s boundaries. Most such deaths occurred after the onslaught of loyalist sectarian killings launched in the early to mid-1970s against Ardoyne and other isolated nationalist areas, exemplified in the activities of the Shankill Butchers. There were also at least eight members of the RUC/UDR and 22 members of the British army killed within the district. Most of the state security forces that died in Ardoyne were killed by the local IRA. Virtually all of these deaths took place in the early years of the conflict. For example, at least 19 British soldiers had been killed in Ardoyne by the end of 1973. It is worth noting, perhaps, that before the introduction of internment (in August 1971) there had been just three such casualties; in the next 14 months a further 15 were to follow. The last member of the regular British army killed in Ardoyne was shot dead in 1977, almost a quarter of a century ago. As has already been stated, whatever its focus, it is not the intention of this book to try to in any way diminish or marginalise the sense of loss that such deaths brought in their wake for the friends and relatives of such victims of the conflict. The intention is, however, to tell the stories of the loved ones of the dead of Ardoyne, who have for many years suffered from having their stories, their lives and their suffering diminished, marginalised and wilfully misrepresented.

Having established that the book would be concerned only with those people who had at some point been residents of Ardoyne, the next practical task for the group was to draw up a list of victims’ names and contact addresses. No definitive list existed. We compiled our own list from a number of different sources, including the republican plaque in Ardoyne, books, pamphlets and word of mouth. This was a difficult process because a number of residents had changed address or moved out of the district. Tracking them down wasn't easy. The database was continually updated and as the research uncovered more and more victims’ names, the number initially thought to be 75 increased to 99 victims. Indeed, this may not be a definitive total but is as close to one that the ACP have been able to establish. The names and addresses of all relatives, eyewitnesses and friends were also included on the database. This was a huge, difficult and time-consuming task to undertake given the number of people who were eventually interviewed. However, the database was essential in order for interviewers to make initial contact with relatives and friends, to set up interviews and eventually return edited testimonies for comment and approval.

Unlike many other parts of the North, the people of Ardoyne suffered attacks and fatalities throughout every phase of the conflict. While bare statistics cannot tell the true story of loss it might be useful to outline a general profile of the Ardoyne dead. Of the 99 men, women and children from the Ardoyne community who were killed, the first (Sammy McLarnon and Michael Lynch) were shot dead by the RUC on the night of the 14/15 August 1969, in the earliest days of the ‘Troubles’. The latest (Brian Service) was killed by loyalists on Halloween 1998. However, reflecting wider patterns, there were a greater number of victims in the earliest years. By the end of 1973 Ardoyne had already suffered 33 deaths, roughly a third of all those who were to die throughout the conflict. Of these, a large majority (19) had been killed by members of the RUC or the British army. The state was ultimately to be directly responsible for 26 deaths of people from the district, 28 per cent of the total. Loyalists killed a further 50. Of the various republican groups the IRA was responsible for nine deaths (roughly nine per cent), the ‘Official’ IRA for one and the INLA for three. Six more people were inadvertently killed whilst on active service with the IRA. One other died accidentally and in three cases it has not proven possible to clearly ascribe responsibility. Of the 99 killed eight were women. The youngest victim was Anthony McDowell, aged 12, shot dead by the British army on April 19, 1973, and the oldest was Elizabeth McGregor, aged 76, shot dead by the British army on January 12, 1973.

Community and Clarifying Geographical Boundaries

Given that the criterion used to draw up the list of victims was one-time residence within Ardoyne, a key issue was clarifying the actual geographical boundaries of the district. This also raised some important questions about the nature of community and the role of collective memory within it. Ardoyne is a readily identifiable place, both historically and today. However, the boundaries of communities do not exist merely, or even primarily, due to lines on maps. They exist in the way, and with whom, people live their lives, share their experiences and identify themselves. Ardoyne is a particular place because the people who make up this tight-knit community live it as such. Indeed, that very collective solidarity proved to be one of the community’s most vital resources during the most difficult days of the conflict. To be from Ardoyne usually means to have been born and grown up in certain streets. It is, in other words, to share a certain sense of place and belonging and to live that out in the contacts, actions and institutions that make up everyday life. This is hardly unusual. Most people and places exist in just this way. It is, more particularly, what the ‘working class city’ invariably looks like. When people in Ardoyne therefore sought to remember their dead and commemorate their lives it was, in many ways, simply a reflection of this seemingly obvious, almost unconscious sense of identity and belonging.

The stories of the people who died from Ardoyne are, in the first place (and most importantly), the personal memories of those who knew and loved them. In another way they are also, however, a key component of a collective memory through which a shared identity takes shape. They are part of the fabric of what makes this community see itself as a community. Indeed, the strong bonds of interdependence that helped hold the area together also ensured that the (unquestionably more distressing and traumatic) individual loss experienced by those closest to the victims had a powerful impact on the rest of the community. This was perhaps particularly so for those who lived through the worst days of the conflict. It was this sense of place also, therefore, which informed the way that the geographical boundaries of the project were clarified, and moulded the focus of the study.

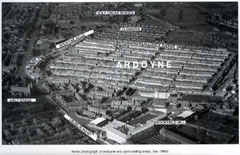

In practical terms this approach still required that very specific lines defining the geographical limits of the area be drawn up. For those who come from Ardoyne, and those (both nationalist and unionist) who live around it, where Ardoyne starts and ends is, generally speaking, very clearly understood. Who is and is not from Ardoyne is generally seen as a matter of common sense. Of course, the boundaries of Ardoyne are to some degree defined by the political divisions, sectarian geography and history of conflict that has shaped North Belfast. Ardoyne is an overwhelmingly nationalist/republican area of around 11,000 people, surrounded on three sides by unionist/loyalist areas. Certain parts of Ardoyne were at one time more ‘mixed’. However, during the 1969-1971 period there was a substantial movement of people into and out of the district. This not only ensured that the population of the area became more homogenous but that its boundaries were also increasingly clear and socially and politically significant. Ardoyne became a nationalist island in a loyalist sea, shaping a growing sense of siege and isolation.

However, for those unfamiliar with North Belfast it is perhaps important to stress that by no means all such boundaries are ‘sectarian’. Indeed, even within Ardoyne there was a traditional (if generally good natured) ‘divide’ between the older, narrow streets of ‘Old Ardoyne’ and the somewhat more substantial houses of Glenard that had more to do with relative affluence than anything else. There are local boundaries that demarcate the district from other neighbouring and mostly nationalist communities like the Bone, Ligoniel, Cliftonville and Mountainview. These boundaries also shape local identity. For example, the Bone is a small nationalist/republican area (originally of no more than three or four streets, though much expanded today) that lies directly adjacent to Ardoyne. Yet the Bone has its own distinctive sense of history and place in the mosaic of territories that make up this part of the city. It is a place unto itself with its own sense of identity. All that said, some geographical boundaries have altered and become slightly more blurred over the years, largely as a result of demographic shifts and urban redevelopment. Streets that were once regarded as the Bone are now part of Ardoyne and vice versa.

Therefore, having decided on the limits of the project, it was necessary to clearly define and agree upon which particular streets were to be included and, more importantly, which were not. The ACP was very aware of the sensitivities of neighbouring communities who have suffered equally as a result of the conflict. There was a particular concern that other areas should not feel excluded by the work of the project. As a result, a number of approaches were made to community groups (for example, in the Bone and Ligoniel) to explain the reasons for restricting the research project to Ardoyne and to encourage them to undertake similar projects. Again, this reflected a key approach by the ACP that only communities themselves can tell their own stones. It is because of this that, for example, a number of civilians killed in Ardoyne (both nationalist and non-nationalist) who were not, and had never been, residents of the district, were not also included in the book. However, there were a small number of victims, from areas adjacent to Ardoyne, (for example, Geraldine McKeown from Mountainview and Joseph Rosato from the Deerpark Road) that were included because they did not readily fit in with any particular community and had well-established links or roots in Ardoyne. In addition, several victims from the Bone (Jim Mulvenna and Sean Campbell) have been included because they died alongside victims from Ardoyne in the same incident. Such decisions were the subject of a great deal of thought and it was a process that finally produced the list of 99 that make up the lives told in this work.

Methodology and Processes

This book is based on interviews with over 300 people. Interviews were carried out with victims’ relatives, friends, eyewitnesses and key individuals within the Ardoyne community. Each victim’s story is made up of a case study that usually contains at least two or three (sometimes more) interviews. In the main the interviews also provided the basis for the biographical detail contained in the boxes that proceed each case. Photographs of the victims were also, wherever possible, obtained directly from the closest relatives. Driven again by the desire to avoid any ‘hierarchy of victimhood’, cases were kept to an equal length as far as possible. However, some cases are longer or shorter than others. This was usually due to the varying levels of detail and insight given by different interviewees. It was notable, for example, that there was often less material available for many of the younger victims. This did not reflect any lack of concern or desire to tell such stories in full. Rather, it says much about the lost opportunities that such young lives being cut so short entails. The testimonies were also edited, with the consent of the interviewees. This was a task that took a great deal of time and work.

In a small number of cases there were less than the average of two or three interviews, in a few, no interviews at all. This was usually because, in spite of strenuous and exhaustive efforts, no relevant interviewee could be found to provide their testimony. In such instances, and in others where it was felt that the interviews needed to be supplemented, the ACP has tried to compile information from alternative sources. These included newspaper articles, coroner’s reports and other relevant official and media material. Given that such sources have not always been seen to provide reliable objective information, where possible reliance upon them was kept to a minimum or cross-referenced with other available evidence. Throughout the project sought to prioritise the voices contained in the testimonies and the wishes and views of the relatives. This was reflected in the way that the list of possible interviewees was drawn up. Initial contact was made with the closest next of kin (i.e. mother, father, husband, wife) whose permission was sought for an interview to be carried out. If it was granted, the victims’ families were then asked to suggest a close friend, eyewitness or other significant person to be interviewed. Over time other possible avenues were pursued to try to build up a rounded portrait of the life and death of each victim. This process took a great deal of time and effort but helped to ensure that relatives were always kept central to the research process.

Individuals interviewed for the history chapters were ‘selected’ after consultation with a variety of sources within the community. The ACP objective was to interview a sample of people that would reflect a broad spectrum of views in the district. These interviews were carried out by those charged with the responsibility of producing the historical context sections of the book. The interviews therefore informed and shaped the content of the history chapters that in turn reflect the themes, issues and concerns raised by the community members consulted. The ACP felt that it was important to put victims’ deaths into historical context and illustrate that they did not take place in a political vacuum. As discussed in the historical chapters, there are clear discernible patterns, linked in particular to British state strategies, that contextualise the deaths. Although direct interviews are the basis of the information used in the history chapters, other primary and secondary sources were utilized to back up the analysis and highlight contradictions in official accounts and discourse (see select bibliography). That said, it is important to stress that the book does not claim to be a definitive oral history of Ardoyne or even an exhaustive political analysis of the conflict played out in Ardoyne. It is one community’s attempt to try and make sense of events that contributes to a much wider jigsaw of lived experience throughout the Six Counties. The book deals primarily with a specific period in recent history and a particular overarching theme — political violence and its impact on the members of this working class nationalist community. Having said that; the testimonies do provide fascinating insights into the broader social, political and economic conditions of the time. A number of those interviewed for the historical sections have since died, including Jimmy Barrett, Rose Craig, Mickey Lagan, Tom Largey, Patrick McBride, Agnes Mulvenna, Bobby Reid, and Rose-Ann Stitt.

Carrying out the testimony interviews involved a fairly steep learning curve. In retrospect a number of ‘mistakes’ were made in the early stages, largely probably due to lack of experience. For example, the designing of the interview question schedule, method of recording the testimony and means of collecting the interviews all evolved over time. Similarly, some of the recording equipment initially used was found to be unsuitable. The individuals who carried out the interviews were Ardoyne residents or people who have very close links with the community. As has already been noted, this was essential in order to gain the trust and confidence of those being interviewed. All interviews were recorded and transcribed, after which they were carefully edited. Volunteers who had a deep personal and political commitment to the project undertook all these tasks. It was felt that, wherever possible, interviews should be carried out in the participant’s home or a venue of their choosing. This is what usually occurred. Given the very sensitive nature of the interviews it was hoped this approach would help put those interviewed at their ease and give them a sense of control over the proceedings. Nonetheless the interviews were an emotional and sometimes difficult experience for individuals and families. Conducting this large number of often lengthy and difficult interviews was also a time-consuming process that undoubtedly took its toll, not only on relatives, but also the volunteers, who recorded the testimonies and transcribed and edited their words. That said, the feedback received from relatives does suggest that the process was important and in general had a very positive and cathartic effect on family and friends.

An absolutely critical aspect of the project was the ‘return’ phase. Every effort was made to ensure that all individuals interviewed received a copy of the victim’s edited case study (i.e. two/three/four interviews). The testimonies were hand-delivered to participants’ homes with a letter explaining that they were free to make changes or include additional information to their own testimony. They were also invited to make comment on the overall case study but changes to other testimonies, could only be authorised by the person interviewed. Several weeks later testimonies were collected. Volunteers spent considerable time in people’s homes talking through, clarifying and meticulously documenting any changes individuals had requested. Participants were asked to sign the returned testimony indicating consent for publication. The final case presented in the book had to be approved by the family or closest relative.

The process of returning testimonies was fundamental to the project. However, the extent of the task was completely underestimated. Moreover it presented the ACP with a whole series of sensitive issues we had certainly never anticipated. The sheer length of time the process demanded and the patience and commitment it required is simply impossible to convey and quantify. Yet for all of us involved in the research the community’s control and ownership was the essence of the project. It is what distinguishes this book from other similar pieces of work. We regarded this aspect of the work, despite the complications, as an essential process to undertake.

There were, at least, three reasons for the decision to return complete edited case studies to participants. Firstly, the ACP felt that it was important that those interviewed had control and ownership over what was written. It was felt essential that they had an opportunity and space to comment on their edited testimony and to give their consent for publication. Secondly, it was important that relatives were given an opportunity to read what other participants had said about their loved one during interviews. While the ACP made it clear that they could not change the words of other peoples’ interviews we actively helped to resolve any misunderstandings or issues that arose. The ACP was called upon to undertake this mediating role on a number of occasions. Thirdly, returning the testimonies was a way of disclosing ‘the truth’ or details about the circumstances of death that had been ‘hidden’ or lost in the chaos of the time.

These issues will be discussed more fully in the conclusion of the book. However, at this point it is important to say that one of the striking things for those of us involved in the project was the realisation of how little relatives actually knew about the circumstances of the death. A surprising number of relatives had never spoken to eyewitnesses or individuals who had been with their loved ones when they died. This is completely understandable given the trauma, confusion and bewilderment in the circumstances of that time. Moreover, countless families up until now have never spoken about the death of their loved one, and as a result, such information was never shared or disclosed at a community level. The project has provided a mechanism for such stories to be told.

A further recurring theme in testimonies that will be examined later in the book was the complete sense of alienation people felt from the institutions of the British state and the whole process of investigation, inquest and disclosure. The hostility and obstruction ordinary people experienced when attempting to establish ‘the truth’ from a system that had long practised a culture of denial and secrecy was in the end too much for many people to cope with. This is evident in the testimonies of this book in particular where agents of the state were involved in the killing. This has meant that over the years some victims’ relatives reluctantly resigned themselves to the fact that they were powerless in view of the odds stacked against them. In later years this created, for some relatives, a misplaced feeling of guilt. Yet in the face of adversity many individuals found ways to challenge the system, struggled and refused to accept. How the British state managed ‘the truth’, and the ways in which local people responded, are explored in some detail in the history sections and conclusion of the book.

The Value of Memory

The testimonies in this book are important for a number of reasons, not least because they allow ordinary people to tell their story. In doing so they challenge perceptions of the past. The last few years has seen a ground swell of community-based groups and projects that are raising the question of ‘state-sanctioned forgetting’ through oral history and commemoration projects. They share the demand for society not to forget and aim to preserve communal collective memories of the conflict, struggle and resistance as a counterweight to ‘official histories’ in the future. The collective memory recovery work being undertaken by groups like the Ardoyne Commemoration Project bear a strong resemblance to that of organisations such as the Recovery of Historical Memory project (REMHI) in Guatemala and other ‘Never Again’ projects initiated by civil society in Latin America.

However, what is apparent is that there are many families who have a deep and fundamental need to know the truth surrounding the death of their loved one. Uncovering the truth and public acknowledgement of wrongdoing by the British state are seen as an essential part of the healing process for many victims’ families. But the fundamental problem remains: where there has been no radical change in government how can the state be persuaded to tell the truth?

It is within this context that groups and organisations like the ACP, operating within civil society, have taken up the challenge of ‘truth-telling’ by trying to establish unofficial mechanisms through which to confront the past. Such voices are becoming steadily louder and better heard; their discourse on truth and justice has come to occupy a more significant position in the public space than before. It is also apparent that these processes are creating awareness and politicising individuals and groups within nationalist communities. In essence a social movement for truth and justice is evolving in the North of Ireland. Until now many individuals and families have struggled privately and in silence with the unresolved issues surrounding the death of a loved one. These ordinary people have had first hand experience of a long-standing practice by the British state of marginalising their experiences, their status as victims and their memories. The growth of the sort of social action described in this book, and indeed the book itself, is a response to the ‘state-sanctioned discourse of forgetting’ explicit in the Bloomfield Report and which underpins the state’s ‘victims agenda’. Like many other societies experiencing conflict transition, there is need to establish truths, in part to preserve an accurate historical account of the conflict, and in so doing ensuring that such human rights abuses never happen again.

The process of ‘post-conflict transition’ presents difficulties in getting at ‘the truth’ in other ways. There have been ‘silences’ within a community like Ardoyne as well as surrounding it. For many years there has been a reticence to discuss fully and publicly events and issues that have touched on many aspects of the conflict. In large part this is a product of a ‘secrecy is survival’ mentality. That was the consequence of subjecting communities like Ardoyne to extreme levels of state surveillance and psychologically destructive counter-insurgency strategies. In addition, it could be argued, the Catholic working class culture that predominates in Ardoyne is not one that lends itself easily to public discussion or display of loss. Such things have also moulded the way that collective memories have been conditioned and shaped. The aftermath of conflict can open spaces for ‘history from below’ perspectives to challenge ‘official’ discourses and public memories. If they are to do so, however, there is also a need to overcome the (understandable) reluctance to place the ‘hidden transcripts’ of the community past on record. It may well be speech, rather than secrecy, that ensures the survival of such memories into the future.

Structure of the Book

The overall structure of the book is built around a series of chronologically organised chapters that are designed to highlight distinct phases of the conflict. In turn, those phases were largely defined by the changing counter-insurgency strategies and policies of the British state that had such a devastating impact on Ardoyne. The consequences of these strategies are reflected in the changing circumstances of many of the victims’ deaths and the testimonies. Each chapter therefore begins with an historical context section that describes how events developed within Ardoyne and elsewhere during a specific time frame. This is then followed by the individual cases of all of the Ardoyne victims who died during that period. Each case includes a photograph of the victim where one was available, key biographical details and the testimonies of the relatives, friends and eyewitnesses interviewed.

Six phases of the conflict were identified. The first was from 1969 to 1970. This was marked by the invasion of the district by the RUC and loyalist mobs on the night of 14/15 August 1969. Hundreds of houses in several streets were set alight and the district suffered its first two fatal casualties. These events are treated in some depth because they were seared into the collective consciousness of the community and did much to define what was to happen thereafter. The next chapter, and one of the most extensive, deals with the period from 1971 through to 1973. Throughout the North 1972 witnessed more deaths than any other year and Ardoyne was to similarly suffer more losses at this time than in any other phase of the war. The introduction of internment in August 1971 and killing of 14 unarmed civilians on ‘Bloody Sunday’ in Deny in January 1972 instigated open war. Such events also exemplified a particular phase of British counter-insurgency strategy that was characterised by militarisation and the mass use of the army in open confrontations and search operations in nationalist areas. This is one reason why British army casualties in Ardoyne were so high during this time. Over 90 per cent of all the British soldiers killed in the district throughout the 30 years of the conflict died in these years. In part as a response to the extent of casualties being inflicted on the British army the state’s strategy was already becoming more streamlined, concerted and guided by key counter-insurgency strategists by 1974. Ardoyne deaths from British army actions decreased from the 1971-73 highpoints, but still remained very high. Of growing significance, however, was the role of loyalist paramilitaries and the issue of collusion. The UVF and UDA embarked upon a nakedly sectarian murder campaign that grew in intensity and ferocity between 1974 and 1976. North Belfast became synonymous with such killings due, in particular, to the actions of the Shankill Butchers, who made the area their sectarian hunting ground. Marking this wave of terror the Cliftonville Road, which borders onto Ardoyne, was re-christened the ‘murder mile’. In these two years 22 people from Ardoyne were killed, 16 in sectarian attacks at the hands of loyalists.

By 1976 the British strategy of Containment was being implemented through the three allied policies of Criminalisation, Ulsterisation and Normalisation. The notional return to ‘police primacy’, the revising of emergency legislation, the creation of special courts and ‘interrogation centres’ foreshadowed the attempt to criminalise resistance to the state. The newly built cells of the H-Blocks were soon filled with the young of (mainly nationalist) working class areas, including large numbers from Ardoyne. Such strategies culminated in the republican hunger strikes of 1980 and 1981, events that re-defined politics for decades to come. In the years immediately following the hunger strikes British state attempts to curtail opposition saw it adopt the ‘supergrass’ strategy. This again had a direct and potent impact upon the people of Ardoyne during the Christopher Black case. Throughout this period sectarian assassination continued to be the dominant cause of deaths in Ardoyne.

The next identified phase begins with the signing of the Anglo-Irish Agreement in 1985 and ends with the declaration of the IRA cease-fire in August 1994. Politically this period was defined by the long, slow and often unclear germination of the subsequent peace process. On the ground real change seemed a very distant prospect. Certainly the rate of fatalities suffered generally in the North had by this time achieved an unwelcome equilibrium, although from the late 1980s onward an increase in loyalist paramilitary activity once again drew attention to the spectre of collusion. Allegations of collusion between loyalist groups and various British intelligence agencies (M15, Military Intelligence, including Force Research Unit and RUC Special Branch) came more and more to the fore, particularly after the ‘shoot-to-kill’ debate was made public during the Stalker affair in the mid-1980s. Certainly in Ardoyne the primary responsibility for deaths continued to be loyalist paramilitaries and although the numbers killed were far less than’ in the early to mid 1970s, there were nevertheless losses in most years. In a number of such cases evidence has pointed to the possibility of collusion playing a part.

The final chapter covers the period of the Irish Peace Process. While it was hoped that the Peace Process would ensure that tension was lessened and deaths from political violence would become a thing of the past this has not, unfortunately, proved to be the case. Certainly’ many things have changed and the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in April 1998 signalled a truly historic opportunity for real social and political progress. The Peace Process also engendered reflections on the history of the conflict as the chance emerged, for the first time in two generations, to consign deaths from political violence to the past. Yet these were years too when inter-communal tensions were enflamed, particularly during the months of the Orange ‘Marching Season’. Whatever the possibilities of finding a better future, the legacy of issues from the past had clearly not yet been put to rest.

It was also in these years and within this environment that the ACP was established. The aim of the project has been to bring into the public arena the story of those people from Ardoyne who lost their lives during the many years of war. As has been stated, the desire is not to write a definitive history of the district or of the conflict, but to show, through the words of those most directly affected, how the conflict impacted upon the district. At the start of the project, in 1998, we had hoped that the last of the political killings had already occurred. Three months later Brian Service was killed by loyalists. Another family experienced grief and loss at first hand. Another name was added to the list of Ardoyne victims. It was a salutary reminder of why this book needed to be written. The hope is that by giving the families and friends of the dead to tell their truth, and contributing in the search for justice, it may be possible to help ensure that the latest victim becomes the last.

- These figures are taken from a number of sources including; Fay, Marie-Therese et al. (1999) Northern Ireland’s Troubles: The Human Costs, Pluto Press, London; McKitterick, D. et al. (1999) Lost Lives: The Stories of the Men, Women and Children who Died as a Result of the Northern Ireland Troubles, and Sutton, M. (1994) Bear in Mind These Dead: An Index of the Deaths from the Conflict in Ireland 1969-1993, Beyond the Pale Publications, Belfast.

'Ardoyne: The Untold Truth'

List of Contents

Introduction

Testimonies

Conclusion

Community, 'Truth-telling' and Conflict Resolution

Report

|