CAIN Web Service

CAIN Web Service

Extracts from 'NO GO - A Photographic Record of Free Derry',

by Barney McMonagle

[CAIN_Home]

[Key_Events]

[Key_Issues]

[Conflict_Background]

Photographs: Barney McMonagle ... Page Compiled: Fionnuala McKenna

The following photographs and extracts have been contributed by the author, Barney McMonagle, with the permission of Guildhall Press. The views expressed in this section do not necessarily reflect the views of the members of the CAIN Project. The CAIN Project would welcome other material which meets our guidelines for contributions.

The following photographs and extracts are from the book:

The following photographs and extracts are from the book:

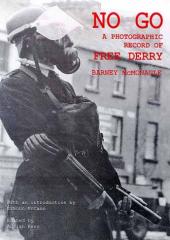

NO GO

A PHOTOGRAPHIC RECORD OF FREE DERRY

by Barney McMonagle (1997)

Edited by Adrian Kerr

ISBN 0 946451 41 9 Paperback 120pp

Orders to:

- Local bookshops, or

- Guildhall Press {external_link}

- Unit 15, Rath Mor Business Park

- Bligh's Lane, Creggan

- DERRY. Northern Ireland.

- BT48 0LZ

-

- T: (028) 7136 4413

- F: (028) 7137 2949

- E: info@ghpress.com

This section is copyright © Barney McMonagle 1997 and is included

on the CAIN site by permission of the author and the publishers. You may not edit, adapt,

or redistribute changed versions of this for other than your personal use

without the express written permission of the author or the publisher, Guildhall Press. Redistribution

for commercial purposes is not permitted.

NO GO

A PHOTOGRAPHIC RECORD OF

FREE DERRY

BARNEY McMONAGLE

Foreword

Introduction

Details of Plates

FOREWORD

Barney McMonagle was born on the island of Malta in October 1944.

He moved to Ireland, to the city of Derry, on 12 August 1947,

where his family settled in Anne Street in the Brandywell area.

He lived there for twenty-two years before moving, first to Shantallow,

then Prehen, and finally to the Culmore road, where he still lives

today.

He first took up photography in 1968, just as the situation in

Northern Ireland was beginning to transform so radically. He felt

that what was happening had to be documented, and, with his camera,

attended most of the major protests and disturbances, taking more

than 1,000 black and white photographs of the events between November

1968 and the late summer of 1971.

He remembers his feelings during the riots, recalling a sense

of excitement more than danger. To most of those involved it was

unthinkable that this could lead to the widespread death and destruction

that followed, and to similar scenes being repeated in the city

almost thirty years later. The real danger was brought home to

him in the late summer of 1971 when, as he was taking photographs

during a disturbance in William Street, a soldier, possibly mistaking

his camera for a gun, took a shot at him, missing him by inches.

He never took another photograph of a riot.

This book is intended to be a purely photographic record of events

in Derry between 1968 and 1971. Brief captions for each photograph

are contained at the back of the book, but there is no attempt

to analyse or to explain. For those interested in a much deeper

analysis of the background and meaning of the "Free Derry"

period the following books are recommended. The list is by no

means exhaustive. Curran, Frank, Derry: Countdown to Disaster

(Gill and Macmillan 1986); McCann, Eamonn, War and an Irish

Town (Pluto Press 1993); McClean, Raymond, The Road To

Bloody Sunday (Guildhall Press 1997); O Dochartaigh, Fionbarra

Ulster's White Negroes: From Civil Rights to Insurrection (AK

Press 1994); O Dochartaigh, Niall, From Civil Rights to Armalites:

Derry and the birth of the Irish Troubles (Cork University

Press 1997).

INTRODUCTION

Time tends to impose order on the past. We look back on the early

days and think we discern the outline of what comes later.

Knowing now how things happened, we assume this is the way it

was bound to be.

But the trajectory wasn't pre-set. The chaos we felt around us

was for real, and rich in possibilities other than those which

came to pass.

The well-composed, neatly cropped photograph doesn't always tell

the truth. The out-of-focus picture is sometimes more accurate.

It's said now with a certain sadness that nothing ever changes.

We inscribe the thought ourselves on our own gable walls: "1968-1997

- No Change". It's the same thought from a different direction

as comes more disdainfully from London or Dublin. The integrity

of their quarrel... attitudes cemented into history... no change,

or changing them, ever.

It's hard to recall now what a heady sense of change there was

then in the trembling Derry air, what a tumult of ideas and bright

seeming glimpses of a different future beckoning.

What was said then was 'Everything's changed. Nothing will ever

be the same again.'

In part, the feeling arose from the fact that, indeed, nothing

at all had shifted in the political landscape, not so that you

could feel it, for a whole half century. There's a story, probably

made up but possibly true, of a ten-year-old girl hurling a stone

down Rossville Street at the RUC and shouting 'I've waited 50

years for this!' Everybody will have known what she meant.

From the earliest I can remember, the Bogside was an immobile

place to live. Society around us was simply-structured, too. The

Unionist minority ran the town and there wasn't much to be done

about it except occasionally indulge in riot and patriotic whimsey,

especially around St Patrick's Day. The first riots I was in the

thick of erupted on 17 March in, I think, 1952. Somebody raised

a tricolour inside the Walls which was accounted sacrilege by

illegitimate city fathers.

'Inside the Walls there were some squalls...

Some Irishmen they raised the flag of orange, white and green,

Brook's RUC would not agree to let the flag be seen.'

So the cops broke Nationalist heads and fighting surged all around

the city centre. The impressive display outside Gault's at the

corner of Little James Street ("Fresh Fruit, Flowers and

Vegetables Daily") was purloined for ammo. A fusillade of

turnips, tomatoes and carrots stopped a baton charge up Sackville

Street.

The Derry Journal published a picture of a cop with a club

about to crack down on the head of Helen Kelly, daughter of Paddy

and Gretta, the horse dealers. It caused no end of outrage at

the time. Eddie McAteer created a fuss at Stormont over it. It

was talked about in Derry for years.

That's how little was happening. Incidents of that sort seemed

of historic significance.

Typical pictures from that period, now commonly seen ornamenting

earnestly authentic pubs, present sepia tableaux of stoic people

with wan smiles, suffused with stillness.

So when the log-jam shifted and a deluge was let loose, the change

was instantaneous and bewildering. The times were now of shemozzle

and hullabaloo, best caught in snatched shots taken on the run.

Nobody had anticipated 5 October 1968, when the first civil rights

march, a few hundred strong (four out of five people who say they

were on it were not) was battered into disarray on Duke Street.

Or, more accurately, nobody had anticipated the response, the

Bogside having little tradition then of vibrant responsiveness.

As far as returning elected representatives was concerned, the

area had been on automatic Nationalist pilot for decades, fervently,

religiously as it might be said, supporting Mr McAteer's party,

it's candidates not so much selected as anointed.

Now all of a sudden, as pent-up anger against the RUC burst forth,

everything was a ferment. Street politics were the order of the

day, and the ideas flourishing on the street were different, new,

exotic, dangerous, exciting. At least in comparison with the stolid

political fare which had been dominant until just a week or so

previous.

To an extent that had never been experienced before, and has never

been repeated since, the mass of the people were active participants

in political events, authors of change, creators of, not spectators

at, the political show. The crowd on the street was the lead actor,

not an amalgam of anonymous extras, or supporters to be summoned

up when a leadership thought it appropriate to stage a mass demonstration.

No political tendency had hegemony. Nationalism still surged strongly,

although now tending to by-pass Mr McAteer's party and beginning

to gouge out the new channels which were eventually to lead to

the formation of the SDLP and the revival of Sinn Fein. Socialist

ideas, some flinty in their absolute ideological correctness,

some flamboyant in their premature celebration of revolution,

some common-sensible, were taken up and debated in lively fashion

all around.

The prominent role of the Derry Labour Party in the street agitation

and civil disobedience which had paved the way to 5 October, and

then the prominence and popularity of Bernadette Devlin from the

far-left student group the Peoples Democracy, gave socialist ideas

resonance and real credibility.

This was the most democratic period Derry has known, when every

voice against oppression was given a hearing and history was not

something we appealed to for validation but something we were

conscious of being in the process of making. It is by no means

coincidence that it was a period of most rapid progress, too.

Effectively, there had been only three Stormont Prime Ministers

in almost half a century, then three in three years and Stormont

abolished when the last of them fell. Gerrymandered Derry Corporation,

the focus of anger against sectarian discrimination since before

the foundation of the State, was whisked away in a twinkling.

The B Specials, the bane of vulnerable Catholics since the 1920s,

were abolished. A points system for the allocation of houses was

drawn up in the time it took to write it down. By March 1972,

41 months after Duke Street, Stormont itself was no more.

The changes that came about may not have been, or turned out eventually

not to be, the changes we had wished. The Specials became the

UDR and then the RIR. Stormont was gone at a cost in a general

curtailment of accountability. And so on. But movement there had

been, after the long years of the political permafrost.

If these weren't exactly the shiny new things we had wanted, at

least the notion of newness wasn't abstract any more. And one

of the advantages of nobody knowing exactly where we were headed

was that you could advocate almost any direction without seeming

daft.

This democracy of the streets is well depicted in these pictures.

It's in the pell-mell rushing of undirected crowds towards a common

objective, in the casual cooperation of young women selecting

throwable stones, in the orderly militancy of a chorus of cat-callers

pressed against a security barrier outside the Corner Boot Stores.

The scenes here are presented from the heart of what's happening.

Every shot is an action shot, but there's none with action orchestrated.

B-Men unsure now in Waterloo Place, b-tech pick-axe handles ludicrous

alongside the BA weaponry, Bernadette as one of the crowd except

that everyone is arranged around her, a water-cannon at McLaughlin

and McLaughlin's squirting a thin jet-stream at something or other,

squaddies with looks of perplexed alarm perusing the Belfast

Telegraph in exhausted Sackville Street, steady handed schoolboys

on pouring duty for petrol bombs... scenes glanced out of the

corner of the eye or taken in when passing by or recorded running

at full tilt amidst mayhem all around or captured in an instant

from a maisonette balcony.

Some of the street-scapes are well past recognition. The houses

that Free Derry Wall formed a gable-end for are gone, changing,

not for the better, the relationship between the slogan and the

entity for which it proclaims liberation. It's an inscription

on a reverential monument now, not a slogan on a neighbourhood

wall.

What hasn't changed is hurly-burly at Butcher's Gate, the carpeting

of William Street in rubble, soldiers erupting into the Diamond

or inching up Rossville Street before making a scurry into rioters

in the hope of bringing a captured native back by the scruff of

the neck, and, always, men uniformed to represent the State in

mutual attitudes of enmity with the plain people of the place.

What hasn't changed either, fundamentally, is what it's about.

The questions posed then had to do with how and whether Catholic

working class areas with their general sense of Irishness might

be incorporated in the State on terms congenial to themselves.

The main reason militant Republicanism won out and for a long

time held dominance over local political thinking was that the

State proved unwilling, maybe on account of being unable, to make

space for the Bogside to exist and develop in.

Politically, that's what's there to be seen in the comportment

of the State's forces.

But now? Can the Bogside become associated with the State, after

all, on terms congenial to itself?

We have passed across pitiful, terrifying terrain to come full

circle, those among us who have made it. Perhaps we can regenerate

our democracy and begin to move forward again, no rigid requirement

to follow a path gouged out by history, no arrogant imposition

of one political morality on all.

What if there is no space for the Bogside even yet within existing

constitutional propriety? Does it follow we must have communal

war and a common ruination?

Or are there different, new, exotic, dangerous, exciting possibilities?

Perhaps stiffened with realism now, and more understanding of

the persistence of elderly notions?

That heady feeling we had back then was a whiff of revolution.

Lenin said that revolution was 'the festival of the oppressed.'

Like the time we were robbing petrol from the garage owned by

Marcus Harrison on William Street and Fr Mulvey arrived in a flurry

of outrage at such disrespect for the rights of private property.

'But, Father,' explained somebody, 'we need the petrol,' and elaborated

further, since the priest seemed unsure that this constituted

adequate moral justification, speaking as one would to a slow

thinker, 'for the petrol bombs...' Mulvey left the scene looking

back, saying, 'alright then, as long as you don't take more than

you need,' and wondering, I think, what our little world was coming

to. To each according to their need, from each according to ability.

What we were hoping, even if we didn't articulate it exactly,

was the world turned upside down, the most festive thought of

all.

Nothing has changed, it's said. But everything must. Unless it's

everything that's being changed we can't bring everybody with

us. Can we free the Bogside into a society in which Nelson Drive

[a Protestant estate in Derry's Waterside], too, would delight

to live?

One solution, revolution.

It was the best and broadest-minded time we have seen, and we

must bring the best of it back.

It's here to be seen, if we look to see it.

Eamoun McCann

July 1997

| KEY | |

| - Walls

| |

| (1) Guildhall | (4) St Columb's Cathedral

|

| (2) The Diamond | (5) Rossville Flats (high flats) - now gone

|

| (3) Free Derry Corner | (6) St Eugene's Cathedral

|

PLATES

| Front cover | RUC Officer in full riot gear, Rossville Street, 13 August 1969.

|

| |

| Plates 1 - 5 | Civil rights protests in Derry, November 1968, organised to protest against discrimination in local government, and in defiance of a Stormont government ban on all non-traditional parades in Derry. Plate 1, Guildhall Square; Plates 2 & 3, Docker's protest in Ferryquay Street addressed by John Hume; Plates 4 & 5, Great James Street.

|

| |

| Plates 6 & 7 | The burning of the "Back Stores" in William Street, January 1969, during an outbreak of rioting following the arrival of the People's Democracy "Burntollet" march in Derry.

|

| |

| Plates 8-10 | An RUC armoured patrol under attack from Nationalists in Rossville Street in the Bogside, early 1969.

|

| |

| Plate 11 | Prominent local civil rights activist Eamonn McCann at one of the many street protests during the early part of 1969.

|

| |

| Plate 12 | Nationalist youths suffering from the effects of CS Gas (Ortho-Chlorobenzal-malononitrile - a chemical used as a riot control agent by the security forces in Northern Ireland), Little Diamond, May 1969. Local residents, without the benefit of police-issue gas-masks, were advised to breathe through a handkerchief soaked in water, lemon juice or vinegar to counter the effects of the gas.

|

| |

| Plate 13 | Nationalist youths preparing petrol bombs, Lecky Road, July 1969.

|

| |

| Plate 14 | RUC using a water cannon in William Street, July 1969. Brightly coloured dye was frequently added to the water to make it easier for the police to identify rioters.

|

| |

| Plates 15 & 16 | A young victim of CS Gas lies unconscious, Little Diamond, July 1969.

|

| PLATES 17-29: | 12 AUGUST 1969

|

| |

| Plate 17 | The annual Apprentice Boys Parade, 15,000 strong, passes through Waterloo Place.

|

| |

| Plate 18 | Local youths, held back by police and Derry Citizen's Action Committee (DCAC) stewards jeer as the parade passes.

|

| |

| Plates 19 & 20 | Police guarding the parade come under attack in Waterloo Place.

|

| |

| Plate 21 | John Hume, Stormont MP for Foyle, attempts to calm the situation in William Street.

|

| Plate 22 | Bernadette Devlin addresses the crowd from a barricade in Rossville Street.

|

| |

| Plates 23 -25 | As the fighting moves back towards the Bogside local youths hold off the police in Harvey Street.

|

| |

| Plate 26 | Bernadette Devlin, Unity MP for Mid-Ulster. She was later sentenced to six months in prison for her actions during the Battle of the Bogside.

|

| |

| Plates 27 & 28 | Scenes of the rioting in Rossville Street, taken from a vantage point in the flats overlooking the street.

|

| Plate 29 | As the RUC, followed by a Loyalist crowd, attempt to enter Rossville Street they come under increasingly heavy attack. They replied with rubber bullets and over 1,100 canisters of CS Gas over the next few days.

|

| PLATE 48-57: | 14 AUGUST 1969

|

| |

| Plates 48 & 49 | As the rioting enters its third consecutive day the B Specials make an appearance on the streets of Derry. Although they didn't become involved, the arrival of a force that was viewed by most Nationalists as a sectarian militia made the already dangerous situation even worse.

|

| |

| Plate 50 | Bogside youths prepare for another day's fighting.

|

| |

| Plates 51-53 | RUC again come under attack in Rossville Street.

|

| |

| Plate 54 | A foreign journalist who got too close to the action is helped by members of the public and an RUC officer.

|

| |

| Plate 55 | RUC Officers fire rubber bullets from Rossville Street towards Abbey Street. The rubber bullets, the predecessors of the plastic baton rounds used today, were 14 cm long and weighed 140 grammes. They caused three deaths in Northern Ireland before they were replaced in 1973.

|

| |

| Plates 56 & 57 | At the end of the third day of fighting the Stormont government is forced to call in the British army to relieve the hard pressed RUC. 300 soldiers of the Prince of Wales Regiment appeared on the streets of Derry at 5.00pm on 14 August. The army were initially given a cautious welcome by Nationalists, but many were sceptical. 'This is a great defeat for the Unionist Government. We do not yet know whether it is a victory for us... The presence of the troops solves nothing. We must not be fooled into taking down the barricades. We do not go back to square one.' (Barricade Bulletin, produced by the Derry Labour Party, 14 August1969.)

|

| |

| Plate 58 | British military personnel in the Bogside, September 1969. The army were initially able to move freely around what were yet to become "No Go" areas for them.

|

| |

| Plate 59 | British soldier on checkpoint duty, Carlisle Road, September 1970.

|

| |

| Plate 60 | "No Way Street." The entrance to the Protestant Fountain Estate from Bishop Street, now permanently closed to traffic, September 1969.

|

| |

| Plate 61 | British troops on the Strand Road in late 1969.

|

| |

| Plate 62 | An injured British soldier is helped away from trouble in Pump Street in the centre of Derry. Their initial welcome soon faded as they came into conflict with Nationalist protesters.

|

| |

| Plates 63 & 64 | British soldiers erecting barricades at the Bishop Street and Ferryquay Street entrances to The Diamond in early 1970.

|

| |

| Plates 65 - 67 | British Army snatch squads in operation after a confrontation with Nationalists in William Street early in 1970. Such confrontations were by now becoming commonplace.

|

| |

| Plate 68 | A British sniper in position at the back of the high flats in Rossville Street, March 1970.

|

| |

| Plates 69-77 | Rossville Street, Easter Sunday 1970. As troops move into Rossville Street they come under stone and petrol bomb attack from Nationalists and snatch squads are sent in to catch the rioters. Even though it is Spring the trees have the look of Winter, their leaves killed by the CS Gas used by the army.

|

| |

| Plate 78 | Lorry used as a barricade in Rossville Street, late Spring 1970.

|

| |

| Plates 79 & 80 | William Street, Summer 1970.

|

| |

| Plates 81 & 82 | Francis Street, Summer 1970.

|

| |

| Plates 83 & 84 | Little James Street, Summer 1970. The top hat was looted from a burnt-out clothes shop earlier in the day.

|

| |

| Plates 85 & 86 | British troops relax in Sackville Street with the daily paper, Summer 1970.

|

| |

| Plates 8 7-90 | British Army Saracens attacked by local youths in the Broadway area of Creggan, September 1970.

|

| |

| Plates 91-96 | Eastway in Creggan, September 1970.

|

| |

| Plate 97 | A photographer gets a close up shot of British troops firing rubber bullets in Abbey Street, Bogside, late 1970.

|

| |

| Plates 98-102 | British patrol in conflict with local youths, Laburnum Terrace, March 1971.

|

| |

| Plates 103 & 104 | British army in action in William Street, Spring 1971. No-one thought to tell them that the bus service to Creggan was always the first casualty of any trouble in Derry.

|

| |

| Plate 105 | A local youth confronts soldiers in riot gear, Abbey Street, June 1971.

|

| Plate 106 | Barricade in Chamberlain Street, facing on to William Street, June 1971.

|

| |

| Plates 107-116 | After British soldiers come under attack at Butcher Gate they chase the rioters down Fahan Street and into the heart of the Bogside, where the riot continues. Summer 1971.

|

| |

| Plates 117-123 | British Army snatch squad in William Street on a Sunday afternoon in Summer 1971. Those caught are brought back to be held behind army lines.

|

| |

| Plates 124 & 125 | A typical afternoon near "aggro corner" in the Bogside as a British army saracen is stoned by local youths.

|

| |

| Plates 126 -128 | Scenes around Free Derry Corner before it became a free standing monument. Late Summer and back cover 1971.

|

|