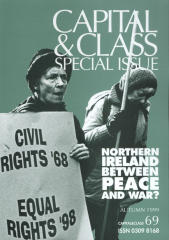

'Northern Ireland between Peace and War'

|

|

Contents |

|

|

vi |

Peter Shirlow and Paul Stewart Military conflict in Northern Ireland is at an all time low yet the Good Friday Agreement has been stalled by the Ulster Unionists. Despite the scope for institutional changes promised in the Agreement there is a persistent malaise whose economic and social roots are constantly nourished by a sectarian state and society. |

|

BEHIND THE NEWS |

|

|

1 |

The Good Friday Agreement, the Decommissioning of IRA Weapons and the Unionist Veto |

|

ARTICLES |

|

|

7 |

Turning Agreement to Process: Republicanism and Change in Ireland |

|

27 |

Who is going to Toss the Burgers? Social Class and the Reconstruction of Northern Irish Economy |

|

47 |

Loyalist Political Identity After the Peace |

|

77 |

The Absence of Class Politics in Northern Ireland |

|

101 |

Policing Ireland |

|

125 |

Masculinity, Violence and the Irish Peace Protest |

|

145 |

Feminist Politics and the Peace Process |

|

BOOK REVIEWS |

|

|

161 |

Michael Pacione (ed.): Britains Cities: Geographies of Division in Urban Britain (Chik Collins). |

Northern Ireland Between

Peace and War?

by Peter Shirlow and Paul Stewart

"

There should be no doubt about Sinn Féins total commitment to implementing the Good Friday Agreement, including resolving the impasse over decommissioning. We want all aspects of this process to work. The choice for the UUP [Ulster Unionist Party] and the British government is clear. Either the Unionist veto continues or the Good Friday Agreement is implemented".Gerry Adams, Guardian, 14/7/99

"

For those who truly want to preserve the union, peace is probably a greater threat than war".John Lloyd, New Statesman, 19/7/99

I

T WOULD BE CHURLISH to deny the level and direction of political change in Ireland over the past decade. Reductions in anti-state and anti-Republican conflict, a cross-border referendum, the creation of a Northern Ireland Assembly and the consolidation at local level in a form of cross-party negotiation all testify to a development in the constitutional political process. Yet to dwell on this aspect of change as only about peace, as media pundits and the Northern Ireland Office have tended to do, ignores some of the realities of political intransigence. These include the Omagh bomb, punishment attacks in Republican and Loyalist areas, Loyalist para-military violence against Catholics notably in the Portadown area (the Drumcree locale) and the disputation over marching and decommissioning. These are signs that in the short-term at least, the causes of political violence and conflict remain unresolved.As we write, The Ulster Unionists have stalled the Good Friday Agreement around their trope of the decommissioning of IRA weapons. The assumption is that by September the three-month cooling off period will see a new agreement between Nationalists-Republicans and Unionists-Loyalists that will somehow resolve the decommissioning issue. Some of the reasons for this parking of the Agreement are beyond our current remit but for the moment we are sure that it poses a number of concerns specifically in the context of Britains claim to have now rejected the time-honoured Ulster Unionist veto. British sponsorship of the Agreement and the wider peace process is given as taken for granted evidence of a renewed disavowal of any strategic or selfish interest in Northern Ireland, which would be placed in jeopardy by defaulting to the Unionist veto.

This veto has to be understood as referring to the Ulster Unionisms presumed right to block any change in the terms and conditions in respect of the constitutional status of Northern Ireland. But what is not sufficiently recognised is that the veto also refers to the way in which relationships between Protestants and Catholics in Ireland can be managed both constitutionally and politically. The Ulster Unionists, so it was assumed historically by the British establishment, were to be given first refusal on any attempts to change the precepts underlying the form and content of these relationships. After the last few weeks of brinkmanship in which the putative Northern Ireland Executive has been put on hold the question is thus whether or not the British Government has now allowed the Ulster Unionist agenda (veto) on decommissioning to hold sway.

And indeed on the wider front, the prevailing political instability reflects the limitations of the current Peace Process. It is increasingly evident that what is being sought via political dialogue was underwritten by pre-existing political assumptions. For the Irish and British states there is a public rhetoric that desires fundamental change or which at least can be construed to the media and keepers of the public conscience as such. Sufficient change will allow the offer of gratuities, enticements and incentives to the political class in the north of Ireland. These, it is rumoured, will provide the opportunity for enforcing a settlement based upon the principle of managing diversity and cultural discord. A related assumption is then made that if what the liberal establishment terms political atavism cannot be eliminated then at the very least it may be contained. Specifically, the two states have been keen to provide the mechanism through which paramilitarism can be diverted into what is deemed to be political normality. An obvious characteristic of conflict resolution in the Irish case is that the illusion has to be created whereby each side will achieve some of its ultimate goals and objectives without being seen to lose face. This process of political confection misses the reality that without the removal of the causes of conflict the discord within Northern Irish society will lie dormant and, as is noticeable at present, reproduce acceptable levels of violence.

Moreover, in recent years we have witnessed a host of policy and peace accords which have apparently focussed on the theme of de-militarisation in several key struggles. The American sponsored so-called peace processes, for example, in the Middle East, Guatemala and Northern Ireland have been sold by the respective national (and international, lest we forget) political classes as the only means for political accommodation that will end cycles of violence which have poisoned relations among different communities. One of the main elements in the search for the various notions of peace has been a recognition by anti and pro-state groups that long-term military conflicts had become futile, especially since many of the victims of conflict were their own People.

Indeed, for Sinn Féin (SF), the Progressive Unionist Party (PUP, aligned with the, Ulster Volunteer Force) and Ulster Democratic Party (UDP, aligned with the Ulster Freedom Fighters) it was the recognition that even with the support of their respective communities they could not, without wider nonrepublican and non-loyalist support, achieve political goals encouraging the development of the imagined road to peace. The unfolding of the Republican and Loyalist cease-fires since the mid1990s has been crucial in the construction of what has been recognised as the so-called Irish Peace Process. The pursuit of civic Republicanism and Loyalism, as articulated in particular by, respectively, SF, the PUP and the UDP, has indicated a tentative disavowal of paramilitary practice through the adoption of more mainstream liberal-democratic strategies.

We need to set-aside for the moment the character and motivation behind the current impasse to look at the wider intention in the Agreement. The drafting of the Good Friday Agreement in t998 and its subsequent support in referenda north and south of the Irish border indicates a further shift towards an institutional political agreement that had been simmering in the mind sets of the British and Irish political establishments for some time. This was further solidified through a re-negotiation of the Irish and British constitutions, including changes to Articles 2 and 3 of the Irish Constitution and the repeal of the 1920 Government of Ireland Act.[1] It was the latter which enshrined the partition of Ireland and consummated a political settlement which had originally divided Irish Unionisman uncomfortable and little remembered piece of Ulster Unionist history. In terms of political identity the aim of the Good Friday Agreement is to achieve a political structure which recognises the contested nature of Irish and British sovereignty. The driving force in this liberal constitutional idea is to endorse the principle of rights and consent by the pro-British and pro-Irish sections of the electorate. This presumes closer involvement between the two states over policy decisions in Northern Ireland, a theoretical form of joint-authority, cross-border trade including cultural exchange and an effective veto over future policies, in Northern Ireland. The key actors in this are to be the elected representatives of Unionism and Loyalism and Irish Republicanism and Nationalism.

In economic and cultural terms, the consensus for something called multiculturalism is being portrayed as the key to reducing the impact of ethnically defined labour markets and regional and local spatial boundaries within Northern Ireland. The two governments argue these are critical in the assault upon the culture of paramilitarism and related notions of cultural oppression and religious discrimination. In terms of conflict resolution the intended aim of the Good Friday Agreement is to democratise a society in which conflicts over sovereignty have undermined any form of cross-community consensus. Furthermore, what may be seen as contradictory processes such as a dilution of British sovereignty via the involvement of the Irish State in Northern Irish affairs, or enshrining the Union via the principle of consent, indicates a strategy aimed at allowing issues of sovereignty to become increasingly opaque. The hope here is that conflicts over territories and places will become less relevant.

A central feature of this wisdom is the belief that diluting the reality of the border in Ireland through increased inter-state harmonisation of social and economic policy, serves to reduce the significance of what the border actually means in terms of sovereignty. There is nevertheless a critical problem with the idea of creeping porosity in the Border since it assumes, or hopes for, amnesia on the part of the Unionists and Loyalists. On the one hand the creation of all-Ireland institutions acknowledges the aspirations of Irish Nationalists and many Republicans, whereas on the other hand, the principle of consent, which has been ratified by both states, guarantees for Unionists the existence of the Northern Ireland State. But of course the creation of cross border institutions would be seen to jeopardise this commitment.

The hoped for outcome is that if, and, or when, cross border institutions are up and running they will work in such a way as to make the Unionists less insecure and the Nationalist less impetuous. In the bright and distant future, continued Irish economic buoyancy will allow Unionists to become cosmopolitans and thus somehow return to their real Irish roots in a united Ireland. Where are the economistic Marxists when we need them! Alternatively, Irish Nationalists in the North, whilst not attaining their perceived goal of a formally united and unitary Ireland, will nevertheless grow to view this as irrelevant since they will have achieved effective integration with a vibrant and prosperous South. Southern capital will flow north and the border, especially around border areas and including the towns of Eniskillen, Newry and Derry, will effectively be integrated into the political economy of the Republic in the south. Though Partition will remain its effectiveness will amount to little more than an institutional formality. This will reflect a time and place in a (European) post-modern political world. For sure, by then, so the idea goes, one side or the other will have given up the ghost. Yet assuredly, post-modern fantasy of the Third Way notwithstanding, the Agreements illusionary capacity operates in such a way that it makes the Border firmer for Unionists, due to the endorsement of the principle of consent, and more time limited for Nationalists where the Irish dimension is endorsed.

Furthermore on the down side, the acceptance of mutual consent, cross-border co-operation and the institutionalisation of communal rights is problematic for many sections of Irish and Northern Irish society. This is especially so for those whose political culture is tied to an unwavering devotion to an ethnically constructed conception of territorial sovereignty. For Irish Republican groups such as the Continuity Irish Republican Army (CIRA), the Real Irish Republican Army (RIRA), the 32 County Sovereignty Committee and Republican Sinn Féin, the onset of closer inter-state co-operation and cross-community dialogue is politically unacceptable if it does not create a sovereign 32 county unitary Irish state. In each case the desire for the re-unification of Ireland is tied to a desire to exclude British state involvement in Ireland. Similarly, for Loyalists such as the Loyalist Volunteer Force, Red Hand Defenders, Orange Volunteer Force and the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) any notion of Irish state involvement in the affairs of Northern Ireland is denoted as a serious breach of British sovereignty and territorial cohesion.

In short, the Good Friday Agreement is a highly ambitious bourgeois democratic aspiration on the part of the Irish and British governments. But it cannot, wishful thinking aside, do more than manage the conflict even if it is seen by the two governments as a process on the road to consensus. But what does this actually mean when one remembers the extent to which state repression remains problematical in more general terms? For sure, the issue of policing is a concern not only for Irish Nationalist and Republican communities. Nevertheless, the character of policing in these communities can reveal much about the processes of continuity between the past and present Unionist political establishment, including the RUC (Royal Ulster Constabulary) and the British state and the persistence of the Northern Ireland state. For Nationalist communities as illustrated by the cases of Pat Finucane and Rosemary Nelson (to name but two high profile solicitors murdered in the last ten years) the question of the relationship between the states repressive apparatuses and Unionist-Loyalist paramilitaries has come to the fore in a particularly poignant way. But the fact is that this repressive relationship is ever present and remains a threat to stability and the development of a non-sectarian political and civil society in the north.

Besides ignoring the realities of the continuity in state repression and sectarianism (the role of the Patten Commission, on Policing, is not in fact the same, let it said, as recognising the salience of state repression) there is a marked failure to explore the realities of social and cultural discrimination. These extend to the perpetuation of masculinised and state cultures of violence. In addition, the realities of intimidation, the physical and cultural subordination of women (Sales, 1997 Heaton et al 1997.) in addition to the political exclusion of the socially marginalised throughout Ireland north and south (see for example MacLaughlin, 1999, on anti Traveller racism in the Republic of Ireland) indicates the limited purview of the Peace Process and its embodiment in the Good Friday Agreement.

A significant indicator of how the wider desire for political transformation has been limited by the obsessive concerns of the political classes in the UK and Ireland has been the focus placed upon decommissioning. Guns for sure are important, but the political question of decommissioning is not, in truth, about guns. The impasse over decommissioning illustrates how wider issues of social exclusion and subordination can be so easily marginalised, put of at best until some future peaceful civil society has restored civic virtues and liberal values. Yet this misses the point being made by many, from the Womens Coalition to the Child Poverty Action Group that something called the peace process fails to acknowledge a dynamic social and political process which cannot be solidified at an institutional level alone. In this sense the decommissioning process has become a cipher and an obstacle for concrete social and economic change in the different and diverse communities both in the North and, in the longer term, the South. Where the issue of the Peace Process is reduced to the matter of guns, then the dynamic for inter community association and working class action across abroad range of social and cultural questions is occluded. If one is uncertain about where responsibility lies for the impasse, then ask the question as to who is likely to benefit from the lack of action on cultural pluralism (north and south) extended fertility rights (north and south) and action on sectarian labour markets (especially in the north).

Whether the Assembly constitutes the denouement of the 30 year duree of social closure and economic sclerosis (see Shirlow and Shuttleworth in this issue) or is yet another temporary halt on the way to a deeper social conflict yet to be divined, we can now see that despite careful planning at least two significant antinomies remain. These are, firstly, the question of the reconcilability, or solubility, of the Ulster Unionist-Irish Nationalist conflict over the nature of the status of the North. Secondly and indelibly linked, is the question of the nature of the state in Northern Ireland. While a contemporary analysis of that peculiar political formation is beyond the scope of this introduction future research will need to address its evolution since the abrogation of Stormont in 1972. Whilst Smyth in this issue assesses the future of one of its key repressive apparatuses, the RUC, greater attention is paid to the relationship between social policy, local ideologies and the persistence of sectarian political relations.

Return to the Northern Ireland State Unionisms nemesis?

Almost twenty years ago the Conference of Socialist Economists published what can still be considered a land mark contribution to the debate on the nature of the state in the north of Ireland. Northern Ireland: Between Civil Rights and Civil War, by Liam ODowd, Bill Rolston and Mike Tomlinson (1980) was arguably one of the most prescient radical assessments of the social, economic and political roots of the crisis of the Northern Ireland State at the time. The aim of the authors was to provide for a broader understanding of the nature of the state in the North than had been offered hitherto.

Their radical agenda for the times was doubly perspicacious for what had been at stake was nothing less than a requirement for a grand departure from existing understandings of the political economy of the north. It is easy in hindsight to forget that radical debate on the left about the north of Ireland from the inception of the Northern Ireland state up until the end of the 1970s, had been refracted through the prism of either anti-imperialist or nationalist discourse. Although distinctive, these sometimes

appeared together as two sides of the same coin as was evidenced in the early period of the formation of the contemporary Republican movement, beginning in the late 1960s. It was not so much that these nostrums were challenged by ODowd, Rolston and Tomlinson, more that they offered up a double challenge to socialists pursuing a radical programme for social change. The task was to demonstrate both the capitalist character of the state and civil society yet also to show how the peculiarities of that society had to be grasped in order, seemingly paradoxically, to illustrate precisely its0 normality. What made the normal capitalist state of Northern Ireland so peculiar?

Northern Ireland: Between Civil Rights and Civil War, broke with existing traditions of left analysis on Ireland in so far as it shifted the discussion away from a one dimensional and ahistorical account of the trajectory of the state. ODowd, Rolston and Tomlinsons argument was that the state had to be understood as embedded in, and constitutive of, social relations of subordination. By this was intended an explanation that rejected an understanding of the Northern Ireland state as in some way above the sectarian divisions of civil society. The alternative, as articulated by prominent early revisionist writers such as Bew, Gibbon and Patterson (1979) was to view anti-catholic state and discriminatory civil society practices as in some sense epiphenomenal and thus accessible to the process of institutional and parliamentary reform. This view of the solubility of the social and economic crisis within the boundaries of the Northern Ireland state was to gain considerable currency on the left over the next twenty years. Yet the revisionist assumption that sectarianism could be removed through broad based structural reform which would leave the state intact so that socialists might then get down to the normal business of traditional bread and butter issue class politics has not been supported by experience. Although ODowd, Rolston and Tomlinson may not have fully drawn out the implications of their critique of the revisionist nostrum for the possibility of reform or revolution, the type of changes they felt were necessary to bring about fundamental social and economic change would have made the Northern Ireland state unsustainable.

Whether the Good Friday Agreement will lead to the Northern Ireland states retrenchment or demise over the next 20-30 years will depend upon the extent to which the political forces in the sectarian civil society respond to the requirements for profound structural economic and institutional reform.

Two Decades On

The work contained within this special edition comes in the wake of other special editions on the peace process which have emanated from journals such as Race and Class, the Irish Reporter and Political Geography. As with these other productions the work contained in this volume aims to raise, among broader issues of political economy, a number of themes around the issues of identity, symbolism and cultural discord. In many ways the critical perspectives offered further the argument that much of what has been achieved within the peace process has been limited by the nature of analysis offered both by political commentators, the two states and the media. If anything, the papers indicate that the political classes and their agents are coping with symptoms of conflict as opposed to those structural relationships that underpin them.

As such the Left still occupies a significant role in the assault upon the myth-making and ineptness of the liberal democratic project in North and South Ireland. However, as indicated in the papers by Finlayson and OHearn, Porter and Harpur, the left remains fragmented both in terms of its theoretical and practical approaches within the wider political landscape. As OHearn, Porter and Harpur observe, the ability of Sinn Fein to advance radical politics may be in question. Here they observe, lies the difficulty of a quasi-radical party working within the structural confines of the peace process. Finlayson, alludes further to the issues of class politics and radicalism. For Finlayson, class plays a role more in the reproduction of political identifications than it does in the evolution of radical politics. For Finlayson, the realities of populist politics, articulated through nationalist ideologies and the myths of peoples further denies the ability to affect a radical political terrain. Both papers illustrate a further reality that although one might observe a radicalism within Sinn Féin and the PUP their ability to cross over the ethno-sectarian divide is limited. This is because in each case radicalism is blunted by alternative perspectives on Irish re-unification.

In addition, Coulter acutely focuses on the need to analyse the presence of social class within the formation of political identity. However, his work stretches beyond the merely descriptive categorisation of class, which he accurately notes is a serious flaw within many academic deliberations on Northern Ireland. In so doing Coulter reminds us how both Catholic and Protestant workers are conditioned either directly or indirectly by the potent symbolic agendas of ethnicity and nationalism. The latter represent a process within which nationalistic allegiances often become the principal determinants of political action.

The processes of industrial restructuring, competing nationalisms, social dislocation and the assault upon civil society by a new consumer-driven capitalism are perpetuating the continuance of an underdeveloped radical space in Irish politics. Both Irish societies will only shift toward democracy via the emergence of a more coherent and radicalised political movement. As indicated by all of the authors in this special issue, the reproduction of poverty, social and economic discrimination, gendered violence and the exclusion of women will not easily be remedied.

As indicated by Bairner and Connolly, particular subordinations in civil society are especially acute as result of given hegemonic forms of masculinity. Both authors clearly indicate the gap between political practice and socially gendered needs. In relation to decommissioning, Bairner illustrates the point that taking the guns out of Irish politics misses a vital ingredient in the problem. He argues that political practitioners rarely, if ever, note the need to decommission the symbolic and physical nature of masculinised violence that exists outside the political sphere. The centrality of male dominance if further elaborated in Connollys analysis of political activity among women and the virtual subordination of their politics within Northern Irish political culture.

The paper by Shirlow and Shuttleworth in addition to that by OHearn et al provides further evidence on the nature of social and religious discrimination within Northern Ireland. In challenging the nature of social democratic interpretations of economic development and equality both papers further the argument that the nature of social polarisation and discrimination has been side tracked within the wider Peace Process. This is especially ironic since the Peace Process is supposedly premised on broad (cross sectarian) notions of inclusion and democratic participation. A similar Janus faced representation of state civility is exposed in Smyths assessment of Policing and specifically the fate of the RUC. Smyth undertakes a historical interpretation of the power invested within institutionalised policing. A power system which is enforced by defacto immunity from prosecution which Smyth argues is a central facet of RUC culture.

The aim of these papers has been not merely to remind the reader of the realities of life in Northern Ireland but instead to highlight the limitation of liberal bourgeois democracy in the reconstruction of Irish society.

Note

1. The revision of articles 2 and 3 of the Republics constitution concerning its relationship to Northern Ireland is dependant upon the setting up of the executive and crossborder institutions as laid down in the Agreement.

References

Adams, G (1999) Sticking to Our Guns, Guardian, Wednesday July 14th.

Bew, P., H. Patterson and P. Gibbon (1979) Northern Ireland 1921-1973: Political Forces and Social Classes. Manchester University Press, Manchester.

Heaton, N., G. Robinson, C. Davies and M. McWilliams "The differences between women are more marginal": Catholic and Protestant women in the Northern Ireland Labour Market, in Work, Employment and Society, Vol.11, No.2: 237-61. June.

MacLaughlin, J. (1999) Nation Building, Social Closure and Anti-Traveller Racism in Ireland, in Sociology Vol.33. No.1:129-51. February.

ODowd, L., B. Rolston and Tomlinson (1980) Northern Ireland. Between Civil Rights and Civil War. CSE Books, London.

Sales, R. (1997) Gender Divided: Gender, Religion and Politics in Northern Ireland. Routledge, London.

Trimble, D. (1999) ...Sinn Féin Have not yet Proved they are Democrats Guardian, Thursday, July 15th.

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||