Chapter from 'Ulster's White Negroes' by Fionnbarra Ó Dochartaigh[KEY_EVENTS] [Key_Issues] [Conflict_Background] CIVIL RIGHTS: [Menu] [Reading] [Summary] [Background] [Chronology] [Main_Pages] [Newspaper_Articles] [Sources] The following chapter has been contributed by the author, Fionnbarra Ó Dochartaigh, with the permission of the publishers, AK Press. The views expressed in this chapter do not necessarily reflect the views of the members of the CAIN Project. The CAIN Project would welcome other material which meets our guidelines for contributions.  This chapter is taken from the book:

This chapter is taken from the book:

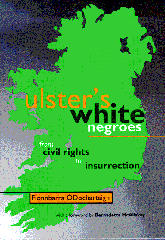

Ulster's White Negroes: Published by:

This chapter is copyright Fionnbarra Ó Dochartaigh1994 and is included

on the CAIN site by permission of the author and the publisher. You may not edit, adapt,

or redistribute changed versions of this for other than your personal use

without the express written permission of the author or the publisher, AK Press. Redistribution

for commercial purposes is not permitted.