"We Shall Overcome" .... The History of the Struggle for Civil Rights in Northern Ireland 1968 - 1978 by NICRA (1978)[KEY_EVENTS] [Key_Issues] [Conflict_Background] CIVIL RIGHTS: [Menu] [Reading] [Summary] [Background] [Chronology] [Main_Pages] [Newspaper_Articles] [Sources]

The period from August 1971 to February 1972 was the last occasion

in which NICRA occupied the centre of the Northern political stage.

Internment produced a party political vacuum which NICRA was able

to occupy by the nature of its broadly based demands. The one-sided

nature of internment, together with the unfolding of the brutality

and torture stories meant that a maximum unity among anti-Unionist

parties was possible behind the banner of civil rights. But the

continued intransigence of the Unionist Government, backed politically

by the Conservative Government in Westminster and militarily by

the British Army, constantly frustrated the civil rights demands

and the ranks of the para-militaries grew accordingly. In late

October, Brian Faulkner produced his Green Paper on the future

of Parliamentary Government in Northern Ireland. After four years

of the civil rights campaign Faulkner was still not prepared to

give an inch. His attitude to the demand for proportional representation,

for example, was unchanged - it was still nothing more than a

possibility. NICRA might have been at the centre of the political

stage, but Unionist intransigence soon thinned the civil rights

chorus line.

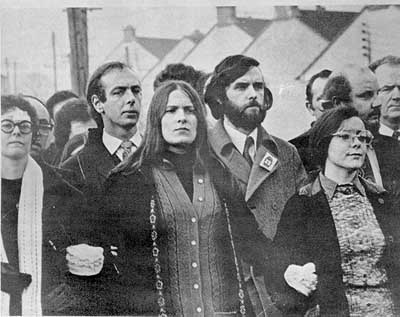

In party politics the SDLP set up an alternative "parliament" in Dungiven which opened on October 26. It was a "Catholic" parliament for the "catholic" people, an attempt to head off the Provisional demand for a Dail Uladh and an effort at short circuiting the demand process of the civil rights campaign. If the Government would not respond to the civil rights demands it was hoped that an alternative "Government" would provide the answer. But it was not a serious effort at an alternative form of administration, more a symbolic gesture of defiance and frustration, a hope that it would embarass the Stormont Government into some form of political reform or that it might force Westminster to take a more active role in Northern affairs. But Stormont was not easily embarassed and the Dungiven parliament succeeded only in completing the political polarisation which had characterised the state for 50 years. If the SDLP were looking for a way to involve Westminster in Northern affairs, it was NICRA which finally provided the straw which broke Stormont's back. In August the Stormont Government's ban on marches had been extended for a further 12 months but in the growing government repression and paramilitary violence NICRA decided that the time had come once more to take to the streets to highlight the denial of civil liberties. It was an attempt to show that the origins of the political unrest in Northern Ireland were the denials of the basic demands for civil rights and a march was arranged for Derry on January 30, 1972.

The events at Derry on Bloody Sunday have been well documented and the full story is told in NICRA's publication "Massacre at Derry". In brief, 13 people were murdered in cold blood by members of the Parachute Regiment [and a 14th died several weeks later of wounds he sustained that day]. Jackie Duddy, Kevin McElhinney, Paddy Doherty, Bernard McGuigan, Hugh Gilmore, William Nash, Michael McDaid, John Young, Michael Kelly, Jim Wray, Gerard Donaghy, Gerald McKinney and William McKinney were among the 20,000 who marched down William Street demanding an end to internment, the introduction of proportional representation, the complete abolition of the Special Powers Act, legislation to guarantee the rights of all political groupings including those opposed to the existence of the state, an end to discrimination, the establishment of an impartial and civilian police force .. They were demanding basically the same reforms which had been demanded on the road from Coalisland to Dungannon in August, 1968. They were demanding the same rights as those who were batoned off the streets of Derry in October, 1968, and now, four years later they were met not with batons but with bullets, and when the guns were silenced the thirteen lay dead. Brian Faulkner and Edward Heath had given their response to the demand for civil rights. To suggest that the Paras ran amok in Derry and that they were not acting under orders illustrates a lack of understanding of the operations of the British Army and a lack of knowledge of the pre-march publicity in the British press. The British Army acted under orders. This was proved by tape recordings of army radio messages and by the concerted and deliberate manner in which the murders were carried out. The pre-march publicity from the Army and the RUC left no room for doubt as to their intentions. They placed the blame for any violence that might occur squarely on the shoulders of the march organisers and several British Sunday newspapers gravely announced on the day of the march that violence was likely but that the Army would take a firm line with it. Having laid the blame in advance they proceeded to take their pre-determined line of action.

Bloody Sunday, like internment, was an attempted military solution to a political problem. Like internment, Bloody Sunday back-fired and the overall joint result of both incidents was the inevitable introduction of direct rule from Westminster. On the Sunday following the massacre at Derry, an estimated 100,000 people turned up in Newry in another NICRA march. It was as much a protest against the Derry killings as a march in favour of civil rights demands, and it proved the peak of NICRA's street success. But numbers on the streets did not necessarily mean support off the streets and the increasing violence meant that if the Newry March was NICRA's biggest, it was also its last significant one. Bloody Sunday was a turning point in the history of Northern Ireland and in the history of NICRA. For Northern Ireland it meant the end of the regional parliament at Stormont. For NICRA it meant the end of the period of mass marches and street rallies. Bloody Sunday was a British Government success in that it immobilised NICRA from returning to the streets, not through imposing fear in the ranks of the marchers, but in finally driving a large section of the apolitical masses away from the concept of civil rights and into the arms of the men of violence. It was in Britain's interest that civil rights should be equated with the abolition of the state. For 50 years the state had thrived on that equation and now in the face of a mass movement demand for civil rights Westminster kicked for touch with the dead bodies in Deny and swung the game once more into a question of the existence of the state. The SDLP fell for the gambit and John Hume said "United Ireland or nothing". Derry's dead killed the civil rights movement by bringing the Provisionals into the centre of the political stage through the immobilisation of NICRA. Unable to win against NICRA, Westminster both changed the rules of the game and selected a new team of opponents.

The British Government could now turn the Northern Ireland question into one of Government versus Terrorism. Civil rights agitation had proved very difficult to deal with, but terrorism would be much easier. Equally for the Provisionals civil rights were a deflection from the mainstream of destroying the state. Taking on the British Army was more understandable than asking for proportional representation. The fight which Britain wanted had now begun - on Britain's terms - and the first necessary political action was to clear the ring. In March 1972, less than two months after Bloody Sunday, Faulkner was summoned to London to meet Edward Heath. It was to be Faulkner's last meeting as Prime Minister. Heath told him that Westminster had decided to take control of Northern Ireland. Stormont, which had looked as if it would last for ever, was gone at the stroke of a London pen. For the Provisionals and several of the anti-Unionist groups, the abolition of Stormont was a major victory. For NICRA, which had fought to democratise Stormont for five years, it was an event of little significance, except that it cleared the political air and quite definitely pointed out Westminster's responsibility for what was happening in Northern Ireland.

The abolition of Stormont also marked the increase of organised Protestant para-military activity in Northern Ireland and the scene was set for a three way battle between the Provisionals, the UDA/UVF and the British Army. In this respect the British Government had certainly a clear objective - a military solution to a terrorist problem. In the rapidly growing terrorist atmosphere in which sectarian assassination and the midnight knock on the door introduced a new dimension in death, NICRA found itself powerless to act in the interest of civil rights as a mass organisation. Street demonstrations were out because of the danger of sectarian violence. If it could not guarantee the safety of its marchers NICRA was not prepared to put lives at risk. At its annual general meeting in February 1972, NICRA formulated its demands in the light of the existing political situation. These included the release of all internees, the ending of a number of repressive laws including the Special Powers Act, the Public Order (Amendment) Act, the Criminal Justice (Temporary Provisions) Act, the Flags and Emblems Act and the Payment of Debt (Emergency Provisions) Act, a radical reform of the entire legal system and the bringing to justice of those responsible for torture and brutality during internment. It was essentially an up-dated package of demands based on those which formed the basis of NICRA's foundations in 1967, but as in 1967, the Government of the day made no effort to respond to the demands in any way. Civil rights had to leave the streets, but the struggle was by no means over.

|

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||