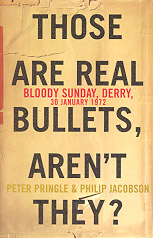

'Those are real bullets, aren't they?' by Pringle and Jacobson (2000)[KEY_EVENTS] [Key_Issues] [Conflict_Background] 'BLOODY SUNDAY': [Menu] [Reading] [Summary] [Chronology] [Dead] [Circumstances] [Background] [Events] [Photographs] [Sources] The following chapter has been contributed by the authors Peter Pringle and Philip Jacobson, with the permission of Fourth Estate Limited. The views expressed in this extract do not necessarily reflect the views of the members of the CAIN Project. The CAIN Project would welcome other material which meets our guidelines for contributions.  These extracts are taken from the book:

These extracts are taken from the book:

Those Are Real Bullets, Aren't They?

Orders to:

These extracts are copyright Peter Pringle and Philip Jacobson (2000) and are included

on the CAIN site by permission of the authors and publisher. You may not edit, adapt,

or redistribute changed versions of this for other than your personal use

without the express written permission of the author and publisher, Fourth Estate Limited. Redistribution for commercial purposes is not permitted.

From the back cover: ‘The only additional measure left is the use of firearms - and innocent civilians would be more likely to be killed than any gunmen’ British Army intelligence assessment, Thursday 21 January 1972 At dusk, Barney McGuigan lay on the pavement in a pool of his own blood and brains, his head blown open by a paratrooper’s bullet. Peggy Deery was near death in hospital, the back of her legs torn away. Frantic relatives searched the morgue for their loved ones. On Sunday 30 January 1972 soldiers of the Paratroop Regiment had stormed into the Bogside shooting dead thirteen unarmed Catholics and wounding a further sixteen. ‘Bloody Sunday’ was the army’s most significant blunder in Northern Ireland, an iconic event that would dramatically alter the course of the conflict. On the verge of defeat, the IRA was instantly revived by a stream of embittered recruits, submerging hopes of peace under a wave of terror bombings, assassinations and ambushes. Despite hundreds of contemporary eyewitness accounts an official government inquiry exonerated the army, blaming instead the organisers of the march and the IRA, whom it said had started the shooting. For nearly thirty years the hidden truths of Bloody Sunday were locked in government files. Vital evidence was gathered at the time by Peter Pringle and Philip Jacobson who were members of the Sunday Times Insight team. Using their unique research plus recently declassified documents and new statements from soldiers, civilians and the IRA, they have pieced together the first narrative history of that terrible day. It provides an intimate portrait of a city in revolt and the climax of a failed military response that plunged Northern Ireland into three decades of armed conflict. This extraordinary account recovers the faces of the soldiers and the gunmen, the stone-throwing youths and the civil rights marchers who came together in a fatal fusion when Britain was at war with its own.

THOSE ARE REAL BULLETS, PETER PRINGLE, journalist and author, has been a foreign correspondent for the Sunday Times and the Observer and for the Independent in Washington and Moscow. He has also written for several American newspapers and magazines. He now lives in New York with his wife and daughter. PHILIP JACOBSON is a veteran foreign correspondent who was most recently chief of The Times bureau in Paris. He has co-authored best-selling books on Northern Ireland and the 1973 Middle East War, and a biography of Aristotle Onassis. Married with two sons (both journalists), he now lives in London.

Street map of Derry in 1972 showing the direction of the Bloody Sunday march.

X

As MICHAEL KELLY LAY dying on the pavement at the gable wall of Glenfada courtyard there was nothing Father Bradley, Father O’Keeffe and a small group of terrified citizens around his body could do to help. They were pinned down by gunfire from the paratroopers. A few feet away, bullets were bouncing off the rubble barricade and chipping the stucco walls. Across the street, people in the flats were shouting warnings that the paratroopers were moving up into Glenfada; the twenty or so men and one woman would soon be surrounded. It was a diverse group of priests, professional types, workers and youths out for some aggro. Some were bound to be arrested because they had been in the mêlée at William Street and were drenched with purple dye from the water cannon. One of those was Jim Wray, the tall twenty-two-year-old with the dark woolly hat who had protested peacefully at Barrier 14 by sitting down in the middle of the road. Another was Michael Quinn, who had just turned seventeen and was still in school; his back was soaked with dye. At least one youth was apparently running the risk of being shot on sight. He was carrying a biscuit tin lid on which lay a number of bomb-like objects. The youth was crying his eyes out. ‘Mister, what do I do with these?’ he sobbed. ‘Get your arse out of here,’ an onlooker told the youth, kicking the tray out of his hands. (It was never clear what the objects were. ‘They looked like fireworks [but] whatever was on that tray never got used,’ said the onlooker.) One member of the group was already known to the security forces, not as a troublemaker but because he worked for the government. Joseph Friel was a twenty-year-old tax officer with the Inland Revenue. He worked in the Embassy building in the Strand Road where the army had an observation post on the top floor and he needed an official security clearance to get into the building. In fact, Friel came of a family who had long served the Crown. His father, who had been in the British army, now worked in Ebrington Barracks as a civilian maintenance man. His grandfather had fought in the First World War and his great-grandfather had also served with the British forces. Friel was on his way to the meeting at Free Derry Corner when he was caught in the gunfire. After lunch at home on the eighth floor of the Rossville flats he had decided to go to Free Derry Corner for the meeting. His father told him to look after himself. None of the lifts in the flats would come to the eighth floor so he ran down the stairs, leaving block 1 at the entrance by the rubble barricade, and headed across Rossville Street. He could hear shouting from the crowd there and loud bangs coming from Little James Street, which he took to be rubber bullets and CS gas. He could also hear Bernadette Devlin’s distinctive voice over the loudspeaker, but he could not see her because of the crowd around the lorry. As Friel reached the speakers at the corner, the shooting broke out and shots came down Rossville Street. ‘The crowd was squealing, crying, roaring and shouting,’ he would recall. ‘I saw sheer unadulterated terror on people’s faces. I froze momentarily and thought where to go. From where I was standing I could have gone in any direction.’ Bernadette Devlin, standing on the back of the lorry, saw the Pigs drive up Rossville Street, and thought they were coming right to Free Derry Corner and everyone at the meeting would be arrested. As she was about to speak, there was a hail of fire and the shots went whizzing overhead. She threw herself flat on the lorry, looked up, covered in coal dust, and saw Lord Brockway, still on his way down, as if in slow motion. She pulled the old man’s ankles from under him. Ivan Cooper was already curled up like a dormouse and she wedged herself in between him and Brockway. Kathleen Meenan and Helen Young, whose brother John was shot dead at the barricade in that first fusillade of bullets, crouched down for cover beside the coal lorry. Someone said the soldiers were firing from the walls, and Famonn McCann came up with another man and they covered the two women with their bodies. When McCann said it was safe, they all began crawling away on their hands and knees. Meenan wore Out the toes of her boots before she had reached the safety of her aunt’s house in St Columb’s Wells. As the paratroopers opened fire, Dr Donal MacDermott, the Bogside GP, was walking down Rossville Street towards the meeting. He had been told there was a wounded man in the flats but had been unable to find him. Now he was worried because he had left one of his sons, Eamon, in his car near Free Derry Corner. Devlin was telling the crowd, ‘Sit down. If you sit down they won’t shoot you.’ Then MacDermott saw Eamon by his car, jumping up and down, crying ‘Daddy, Daddy, they’re firing real bullets.’ MacDermott packed him into the car and drove home. Eriel ran back to the flats, thinking he would also go home but when he arrived at the entrance to block 1 the doorway was packed with people taking cover and he couldn’t get in. The shots were coming faster and louder, it seemed, but he still had no real impression where they were coming from. There was complete chaos on Rossville Street. People were running in every direction and bumping into each other, leaping over the barricade and stumbling as they did so. A woman with a child in a pram got stuck, but people ran on too panic-stricken to stop and help her. Realizing he could not get through the door, Friel crossed over at the rubble barricade into Glenfada Park and reached the gable wall where Father Bradley and others had been attending to Michael Kelly.

Gerry had never had anything to do with the IRA, or even the civil rights organization, and he had never thrown a stone in his life. His only brushes with the law were tickets for parking and speeding. Gerry had no intention of being on the march. He had left home after Sunday lunch to go over to his mother’s house in Beechwood Street at the back of Glenfada. Like all Bogsiders, Gerry was bitter about the treatment of Catholics — because of his religion he had been turned down for several jobs for which he was well qualified, or so he had concluded, and he had found work outside Derry several times. At the start of the Troubles in 1969, he had sent the family south to Dublin for a spell, and since internment, he would not let his wife Ita go into the centre of town — he did all the shopping and ran the errands. But he did let her go to bingo once a week across the border in Buncrana. He had never been unemployed and for the last six months had been working for John McLaughlin, a local builder, and was making a steady £3 5-40 a week, topped up by his management consultancy. Gerry was a generous man, always helping neighbours down on their luck by lending them a few quid and asking every day, as he left home, whether Ita was OK for cash. That afternoon he was due to go into the office to meet his boss McLaughlin to discuss a few business matters and ideas he had for a job in Dublin. The papers were in his car, but he couldn’t get out of the Bogside because the army had closed off the exits. Gerry’s brother-in-law, John O’Kane, and some other friends were at his mother’s and they were going on the march, so Gerry decided to join them.

Willie started work at the Derry Journal when he was fourteen, first as a tea boy and then as an odd job man. On Journal outings to Bundoran, a seaside resort in Donegal Bay across the border, Willie would play the accordion on the bus, mostly Irish folk songs. But his favourite from the hit parade was ‘Where Would You Like to Be? Under the Bridges of Paris with Me.’ He wanted to be a printer but, in those days, first you had to be a member of the printers’ union. McKinney badgered union officials, writing them letters, and they eventually gave in; if the other printers agreed, he could become a member. The others did, because they liked him. When he got the job the family were very proud. He would come home for lunch each day on his bike, and his brothers and sisters would be sitting down at the table, waiting for him. He started dating Elizabeth O’Donnell from the Waterside and they got engaged, but they never married. By chance, he had been arrested once by the army. It had happened late one evening after he had been out with his fiancée. She had gone home, but Willie had stayed to watch a few young lads stoning an army patrol. They were all arrested and held at the barracks until five in the morning. Anyone with dirty hands — showing they had been picking up stones — was charged with riotous behaviour. Willie’s hands were clean and he was not charged with anything. Recently, he had bought a good camera second-hand from the Journal because they had no use for it any more. He was mad about it and used to develop his own film at home, after the family had gone to bed. He kept all his chemicals in old lemonade bottles in the kitchen. The week before he had been to the protest march at Magilligan and had taken pictures there, and this Sunday he was out again with his camera. He had left the house looking smartly turned out, as he always liked to be, with a shirt and tie, a black blazer, his corduroy cap and his dark-grey mohair three-quarter-length coat under his arm, and carrying his camera. He could have been mistaken for a reporter. One of the last to seek refuge in Glenfada Park was Danny Gillespie, who lived in the Creggan, was thirty-two and unemployed. He had been with the march since the Bishop’s Field and found himself standing next to a man who was hit in the mouth with a rubber bullet at Barrier 14 and had to have several stitches in his lip. Gillespie then made his way into Glenfada, warning a group of youths clutching broken-up bits of flagstones that they would be wise to clear off; the paratroopers were firing live rounds.

Joe Friel looked round to the north of Glenfada. He was without his glasses; that day they were being repaired. Even so, he could see paratroopers standing by the garages at the north end of Glenfada, three or four of them. ‘The one in front was firing,’ Friel would recall. ‘He had his gun at just above waist height and was moving it from side to side, not swinging it, just moving it a few inches from left to right. The other soldiers were not firing their weapons. The soldier was not picking me out. The fire was random.’ Friel started to run towards the alley leading into Abbey Park. Suddenly, he felt a thump in his chest. He thought he had been hit by a rubber bullet; he couldn’t believe it was a real bullet because he thought that must feel different — ‘like a red-hot wire boring into you’. He looked down and saw the gash in his jacket and the blood starting to come through his clothing. There was also blood in his mouth. ‘I’m hit, I’m hit,’ he cried. He collapsed into the hands of three men taking cover in the alley. One of them was Leo Young. He was looking for his brother John who was lying dead or dying behind the rubble barricade in Rossville Street. Friel was fully conscious and scared he was going to die, but he had been incredibly lucky. The bullet was ‘an almost near miss’, as the doctor at Altnagelvin would later say. It was a flesh wound; no vital organs or blood vessels had been hit. The bullet had gone clean through the front of his chest, entering on the right side, cracking the breastbone and exiting on the left. If he had not turned slightly to see the paratrooper who shot him when Gregory Wild shouted his warning, the bullet would almost certainly have hit him in the back and probably would have killed him. Young and others carried Friel into the Murrays’ house in Lisfannon Park. He was treated by the young paramedic, Eibhlin Lafferty, who tore open his shirt and put a sterilized pad on the wound. There was a crowd in the house, mostly older women who knelt around him and started saying the rosary. Mrs Murray ran upstairs, unable to take the drama. Joe Friel was convinced he was going to die. When Danny Gillespie first saw the paratroopers come into the courtyard, one of them was directly in front of him, aiming his gun at him from the shoulder. Gillespie turned and ran across the yard and there was a sharp crack. His head was stinging and burning. He fell forwards with his face down on the tarmac. Everything went black. When he regained his senses Gillespie found two of the youths he had told off about carrying stones asking him if he was all right and trying to help him up. He had almost made it to the cover of the alley leading out of Glenfada into Abbey Park when there were more shots and one young man let out a grunt and fell on top of him, pinning his legs to the pavement. Gillespie managed to push him off and run through the alley into Abbey Park. This was Jim Wray.

Seventeen-year-old Martin Hegarty was scared stiff. ‘How do I get out of this one?’ he was asking himself. Several in the group had given up, accepting that they would be arrested, at best. They were squealing and some had their hands over their ears, trying to shut out the commotion and the reality of their plight. Hegarty proposed dashing south into the next courtyard of Glenfada; others were in favour of running across the yard into the alley that led into Abbey Park. ‘Jesus, don’t go out there,’ someone said. But Michael Quinn, a seventeen-year-old schoolboy, was ready to run. Ahead of him he saw a youth shot in the right thigh on the west side of the park. The next moment he looked up he had gone. He was wearing a black anorak and had brown hair. Quinn now ran towards the alley, doubled over. He had taken only a few paces before he was hit. The bullet ripped the right shoulder of his jacket before blowing away a chunk of his cheekbone and came out through his nose. Quinn staggered through the alley into Abbey Park and saw the youth who had been shot in the leg lying on the ground. Someone helped Quinn towards Fahan Street and across open ground to Blucher Street, where he was treated by the paramedics, Pauline Lynch and Eibhlin Lafferty. Others from Bradley’s group now dashed for the alley into Abbey Park. One of them was John McLaughlin, supervisor at the National Coal Board’s yard in the Waterside. Ahead of him was a young lad sprinting for the alley. One of the paratroopers spotted him and swivelled round, aimed at the boy and called out for him to stop, but the boy kept running. McLaughlin took his chance and ran for the alley. The same soldier shouted at him to stop and he saw him swing his rifle round to aim at him, but McLaughlin put his hands on his head, bent double, and just kept going. More people followed. In a fusillade of bullets Joseph Mahon was hit in the thigh and fell, and behind him Willie McKinney, clutching his precious camera, was cut down by a bullet in his back.

Corporal E said when the paratroopers arrived in Glenfada there were about forty or fifty people who started to throw missiles and he saw a man throwing a petrol bomb which landed ten yards from him. He then saw that the same man had a nail bomb and as he was lighting it he shouted to him to drop it, but as he had already lit it, Corporal E fired two shots. The second hit him and he fell down. According to Corporal E, the nail bomb exploded but no one was hurt, but none of the civilians saw or heard any explosion in the confined courtyard. Lance Corporal F, who fired five rounds from Glenfada, would say that he spotted three men who had left the rubble barricade move into the courtyard. ‘One of them turned and was about to throw what appeared to be a bomb (because it was fizzing) in our direction. Myself and "G" dropped down on one knee. I took an aimed shot. The first shot seemed to hit the man with the bomb in the shoulder, the second in the chest. The man fell to the ground.’ The bomb did not explode, Lance Corporal F said. His partner, Private G, said he fired three rounds at two gunmen who were standing on the same footpath leading to the alley into Abbey Park where Friel, Gillespie, Wray, Mahon and Willie McKinney were shot. . . . We moved quickly into the alleyway and I remember looking round for F who was just behind me. There is an archway into the courtyard of Glenfada Park. There was a car parked close to the mouth of the archway and I went round to the right-hand side of the car with F close beside me. As I got round the end of the car two men attracted my attention in the opposite corner of Glenfada Park. These men were armed. I cannot identify their weapons exactly but I think they were short rifles like an Ml carbine. They both had weapons of this sort. I immediately dropped to one knee and fired three aimed shots at one of the men. F was firing beside me and I saw both men fall. Private H fired a total of twenty-two rounds in Glenfada Park, more than any other paratrooper’s total for any of the killing grounds. (Lance Corporal F fired the second highest total of thirteen, five of them from Glenfada.) Private H’s first target in Glenfada, he would say, was a youth who he thought was about to throw a nail bomb. I saw a lad . . . he had an object like a Coca-Cola tin in his hand. He was drawn back in the throwing position. I fired two shots at him and he fell to the ground. The bomb just thudded to the ground without rolling or bouncing. I am still sure it was a bomb. It did not explode. There was an alleyway at the opposite corner of the square from which a youth ran. He picked up the bomb, I think with his right hand, and I thought he was about to throw it. I fired one round at him and think it hit him in the right shoulder or upper arm. He was able to stagger away. He did not drop the bomb. Private H’s next target, he said, was a gunman who was pointing a rifle from behind a frosted window-pane in a house on the north side of the courtyard. He said he pumped nineteen rounds into this bathroom window, but no window was found punctured with nineteen bullet holes and none of the other paratroopers saw or heard Private H firing nineteen shots at one target. The bullets that Private H fired clearly went somewhere else.

Porter saw Jim Wray fall and hit his head on the sidewalk. Then there was a volley of shots. He closed the door and went to the window. ‘My God, there’s a man been shot,’ he told the people in the house. He went back to the door and opened it. He saw Wray lying half on, half off the pavement. His left arm was limp and there was blood on his wrist. Wray raised his head up off the ground and looked towards where Porter was standing in the doorway. Wray then tried to press himself up with his right hand, but he couldn’t move. Porter ran out of the door towards Wray and three bullets smacked into the wall in front of him. He ran back into the house and slammed the door. Malachy Coyle, a sixteen-year-old schoolboy, also saw Jim Wray fall on to the pavement. Coyle had been running away from the paratroopers as they came into Glenfada and had almost reached the alley into Abbey Park when he was grabbed by a man who pulled him to safety into the backyard of a house. It had a slatted wooden fence through which Coyle could see the Paras moving into the courtyard. He was scared stiff. He thought of hiding in the dustbin but it was full of rubbish, so he just crouched down behind the fence. Wray was looking directly at Coyle, raised his head off the pavement and said, ‘I can’t move my legs.’ The bald man who had pulled Coyle to safety told Wray, ‘ Keep calm, keep calm.’ Coyle said, ‘Don’t move. Pretend you’re dead.’ More shots rang out from the north end of the courtyard and the pavement around Wray exploded in sparks. Wray was still trying to raise himself up. From the house he was in, John Porter saw Wray’s brown corduroy jacket jump twice four or five inches in the air and his head went down slowly on to the pavement. Wray had been shot in the back, for the second time. The first bullet, which had apparently caused him to fall so that he couldn’t move, entered Wray’s back from the right and travelled to the left almost horizontally across his back — from the direction of the paratroopers. The bullet damaged the spine at the tenth and eleventh thoracic vertebrae, fractured the tenth and eleventh left ribs and bruised, but did not penetrate, the left lung. The spinal injury meant that Wray could not lift himself up. The second bullet was the one that killed him. It entered Wray’s back, just above the first bullet. Then it passed through muscle tissue, damaged the eighth thoracic vertebra, fractured parts of five left ribs by which time it was tumbling through the tissue of the left lung before leaving the body. The gaping exit wound exposed lacerated muscles. Death, which was not instantaneous, was caused by bleeding and the escape of air into the left chest cavity from the damaged lung. The wounded Joe Mahon watched, terrified, as Wray was shot while on the ground. Mahon was lying behind Wray and saw his desperate efforts to get up. He heard him calling for help to Porter, Coyle and others sheltering in the alley. After Wray was shot the second time, Mahon could hear the soldiers coming closer. He lay still, pretending he was dead. Behind him, Willie McKinney was moaning. Mahon was seriously wounded, but he would live. The bullet had entered the right pelvic bone and tossed through the intestines, splitting up into tiny bits that bored twelve holes in the small intestine and made six separate perforations of the mesentery — the membranes that hold the intestines to the abdominal cavity — before embedding itself in the muscle beyond the bone. (The surgeon who operated on Mahon noted in his report, ‘The bullet was a high-velocity one and such missiles when they penetrate the abdominal viscera, carry a notoriously bad prognosis.’) However, Mahon’s medical report would give no accurate description of the entry wound, as was done for all the other dead and wounded and, although the bullet was found intact, the government forensic staff, while agreeing it had been fired from an army SLR, could not match it to any of the twenty-nine rifles the army would submit for examination. The mystery was why it had split up so readily into tiny fragments without hitting a bone. Behind Mahon, lying face up on the pavement, Willie McKinney was still conscious after being shot, also in the back. One bullet had caused four surface wounds and multiple internal injuries. The entrance wound was on the right side of his back. As it travelled through his body, it fractured some ribs, lacerated the diaphragm, the right lung, the liver, colon, stomach and spleen and then made a hole in his left side big enough for his guts to be hanging out. The bullet then ripped holes in the back and front of his left forearm before leaving his body. A paratrooper, whose footsteps Mahon could hear coming closer, left McKinney alone and walked forward towards the alley. He then fired three more rounds into the alley and Mahon heard him say, ‘I’ve got another one.’ Mahon did not dare move to see what he was firing at. Another soldier said, ‘OK, we’re pulling out.’ Before they left, Mahon saw the first soldier remove his helmet to wipe his brow.

After the rush out of Glenfada through the alley into Abbey Park, people took shelter in and behind the houses there. John O’Kane had run through the alley with his brother-in-law, Gerry McKinney, and they had dived for cover. Through the alley they could see where Wray had fallen in Glenfada Park and wondered how they could reach him. Donaghy was seventeen and an ardent Republican who had just completed six months in jail for rioting. He said he would be able to get to Wray if he crawled on his stomach but as he started out O’Kane and McKinney pulled him back saying it was too risky. There was more shooting and then all three started to move out across the mouth of the alley. People on the other side shouted, ‘Get back, get back.’ O’Kane turned back, but McKinney and Donaghy kept edging out. O’Kane shouted, ‘Come back, it’s not worth it.’ But it was too late. The paratrooper spotted them. Gerry McKinney’s arm was stretched out across Donaghy’s chest, holding him back. He said to Donaghy, ‘Just a minute, son, ‘til we see if it’s clear.’ As he turned his head into the alley to see if it was safe to cross, he spotted the paratrooper aiming at him, his hands shot up in the air and he cried out, ‘No, no.’ Two shots rang out. McKinney and Donaghy fell to the ground. Donaghy was clutching his stomach.

John’s father, Peter, had let the group with Kelly’s body inside the house, then herded all the children upstairs and put four or five of them, including John and the one-year-old baby, in an empty wardrobe, closed the door and told them to stay there. After a minute, John’s curiosity got the better of him, and he came out of the wardrobe and went into his brother’s bedroom at the front of the house. As he looked out of the widow through the alleyway into Glenfada several shots rang out and he saw Jim Wray’s head fall slowly on to the pavement. Then he saw a soldier come through the alleyway and face a group of people who ran away — except for one man who threw his hands up in the air and looked directly at the soldier. The bedroom window was closed and John could not hear whether the man said anything, but as his hands went up, the soldier shot him and he fell on his back. John saw him bless himself with his right hand across his face. It was Gerry McKinney. John screamed out, ‘They’ve shot a man and he had his hands up.’ His father ran into the room, saw John standing at the window, grabbed him and told him to get down on the bed and to stay there while he checked the other children.

Another paramedic, Robert Cadman, joined her. Looking through the alley, Lafferty saw the bodies of Wray, Mahon and Willie McKinney lying on the pavement. There was blood coming from McKinney’s mouth. Cadman saw the barrel of a rifle appear at the Glenfada end of the alley and shouted to Lafferty to stay still but she didn’t hear him. She was bending over Gerry McKinney and Donaghy, and only had time to see they were still alive when there was a shot. The bullet, apparently, hit the cobblestones behind Leo Young and he ducked down on one knee. Lafferty lay flat and shouted, ‘Don’t shoot, don’t shoot, Red Cross.’ Cadman joined her and they moved towards the alley into Glenfada. At the same moment Mahon, who was still pretending to be dead, turned his head to see if the paratroopers had gone and looked straight at one. The soldier got down on one knee and took aim. Just then Lafferty shouted again, ‘Don’t shoot, Red Cross.’ The soldier shouted back, ‘Your white coats are great targets but your red hearts are even better.’ She shouted, ‘Are you mad?’ He didn’t fire and Mahon would later credit Lafferty’s intervention with saving his life.

More people came out to help carry in the wounded. Jim McLaughlin helped get Willie McKinney into 7 Abbey Park. There was a first-aid man with a deformed hand who treated him, and he was struggling with the oxygen equipment and couldn’t put the rubber pipe into the cylinder. They brought James Wray into Peter Carr’s house and put him on the floor in the living room beside Kelly. Malachy Coyle would later describe the actions of Corporal E, Lance Corporal F and Privates G and H. He did not know which regiment they were from — they were all dressed alike, except one who was without a helmet. The soldier without a helmet acted differently from the rest. He entered the car park ahead of the other soldiers and I noticed him immediately because he stood out from the rest by his dress and his manner. He was bareheaded and I could see he had blackish-coloured hair. He was not particularly tall, but he had a wiry build and looked to be very fit and strong. I think he had black streaks on his face. While the other soldiers adopted a defensive position . . . this soldier ran on ahead of them to the south gable end... [There] he discovered between twenty and thirty people all hunched down for cover beside the wall . . . the crowd of people there started squealing. I saw the bareheaded soldier turn around to face the crowd. . . and I heard him shout, ‘I’ll shoot you, you Irish bastards. You Irish scum!’ He shouted this three or four times, very loudly. All the time he was standing with his gun pointing towards the crowd at the south gable wall... I remember hearing a woman’s, or young boy’s, voice crying out, ‘Please don’t shoot us! Please don’t shoot us!’ The bareheaded soldier’s behaviour was weird . . . he was acting completely irrationally and he could not stand still. He kept jerking about in a strange manner. He was very angry. He was obviously totally out of control and he could not stop shouting and screaming and moving about. It was very, very frightening to see him so full of anger and pointing his rifle at innocent civilians . . . I became deeply afraid of leaving the safety [of the backyard] . . . I said to the bald man, ‘They’ll see us soon. We’d better get out and give ourselves up before that happens.’ I remember that the man stood up and went out of the backyard first and I followed him with my hands behind my head. We tensed ourselves as we stood up because we were expecting to be shot. The bareheaded soldier fired again and Coyle ‘lost it’. He panicked and bolted through the alley to the south, ran across the old Bog Road and took refuge with others by a fence. When the others asked him what was going on in Glenfada, he was in such a state of shock he couldn’t get the words out. He broke down and wept.

Bardon, Jonathan, A History of Ulster, Blackstaff, Belfast, 1992 Bew, Paul, Gibbon, Peter and Patterson, Henry, Northern Ireland, 1921-1994: Political Forces and Social Classes, Serif, London, 1995 Carver, Michael: Out of Step, Hutchinson, London, 1989 Curran, Frank, Derry, Countdown to Disaster, Gill and Macmillan, Dublin, 1986 Dash, Samuel, Justice Denied, A Challenge to Lord Widgery ‘s Report on ‘Bloody Sunday’, International League for Human Rights, New York, 1998 Devlin, Bernadette, The Price of My Soul, Pan, London, 1969 Evelegh, Robin, Peace-keeping in a Democratic Society, The Lessons of Northern Ireland, C.Hurst & Co, London, 1978 Geraghty, Tony, The irish War, the Military History of a Domestic Conflict, HarperCollins, Guildhall Press, Londonderry, 1998 Hamill, Desmond, Pig in the Middle, the Army in Northern Ireland 1969-85, Methuen, London, 1986 Hastings, Max, Ulster 1969, The Fight for Civil Rights in Northern Ireland, Victor Gollancz, London 1990 Irish Government, Bloody Sunday and the Report of the Widgery Tribunal, The Irish Government’s Assessment of the New Material, presented to the British government in June 1997 Kitson, Frank, Low Intensity Operations, Faber & Faber, London, 1971 Lacey, Brian, Siege City: The Story of Derry and Londonderry, Blackstaff, Belfast, 1991 Lindsay, John (ed.), Brits Speak Out, British Soldiers’ Impressions of the Northern Ireland Conflict, Guildhall Press, Londonderry, 1998 McCafferty, Nell, Peggy Deery, An Irish Family At War, Attic Press, Dublin, 1988 McCann, Eamonn, War and an Irish Town, Penguin, London, 1974 McCann, Harrigan, Bridie and Shiels, Maureen, Bloody Sunday in Derry: What Really Happened, Brandon, Kerry, 1992 McClean, Raymond, The Road to Bloody Sunday, Ward River Press, Dublin, 1983, 1997; revised edition, Guildhall, Londonderry, 1997 McKittrick et al, Lost Lives, Edinburgh, London, 1999 McMahon, Bryan, ‘The Impaired Asset: A Legal Commentary on the Report of the Widgery Tribunal’, Le Domain Humain, V1,3, Autumn, 1974 McMonagle, Barney, No Go, A Photographic Record of Free Derry, Guildhall, Londonderry, 1997 Mullan, Paul, with John Scally, preface by Jane Winter, Eye-witness Bloody Sunday, Wolfhound Press, Dublin, 1998 O’Brien, Conor Cruise, States of Ireland, Hutchinson, London 1972 O’Dochartaigh, Niall, From Civil Rights to Armalites, Derry and the Birth of the Irish Troubles, Cork University Press, 1997 Purdie, Bob, Politics in the Streets. The Origins of the civil rights Movement in Northern Ireland, Blackstaff, Belfast, 1990 Sunday Times Insight Team, Ulster, Penguin, London, 1972 Taylor, Peter, Provos, the IRA and Sinn Fein, Bloomsbury, London 1997 Toolis, Kevin, Rebel Hearts: Journeys Within the IRA’s Soul, Picador, London, 1995 Walsh, Dermot, The Bloody Sunday tribunal of Inquiry, a Resounding Defeat for Truth Justice and the Rule of Law, paper for the Law department, University of Limerick, January 1997. Winchester, Simon, In Holy Terror: Reporting on the Ulster Troubles, Faber, London 1974 Ziff, Trisha (ed.), Hidden Truths, Bloody Sunday 1972, Smart Art Press, Santa Monica, California, 1999

We began the research on this book in 1998 shortly after learning that the Saville Inquiry had obtained from the Sunday Times our notebooks, witness statements, memos and files from 1972. The Saville Inquiry (Saville) asked us to prepare to be interviewed and sent us a single CD-ROM (No. 5) containing our material. Subsequently, we obtained another nine Saville CDs. These contained documents from the Cabinet Office, the Treasury Solicitor, the Ministry of Defence (MoD), The Northern Ireland Office (NIO), and the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC). This extraordinary archive includes interviews with approximately five hundred civilian eyewitnesses and several hundred army personnel, RUC and government officials, in Derry, London and Belfast, who participated in Bloody Sunday, plus more than one thousand photographs, maps and diagrams. The archive is repetitive — the same statements from civilian eyewitnesses, soldiers and policemen often appearing more than once on the same CD — and then again on the other nine. The new interviews are of mixed value. Our original material is ‘primary source’ — we conducted interviews within a few days, or weeks, of the event, as journalists, not as officials of a government-sponsored inquiry. We were free to ask whatever questions we thought needed answering to put together the first independent account of what happened on that day. Our report was published in the Sunday Times (ST) on 23 April 1972 — five days after the publication of the report of the British government’s official inquiry by the Lord Chief Justice, Lord Widgery (Widgery). Twenty-seven years later, Saville investigators went back to the original interviewees’ interviews and then added new ones —including soldiers who were part of the military force surrounding the Bogside, but who did not fire and had not been called to give evidence at the time. The additional testimony widens the investigation of the killing ground, bringing in more background and detail, and confirms what the first inquiry concluded: that the thirteen who were shot dead were unarmed. So were the fourteen who were wounded. Newly declassified documents fill important gaps in the military preparation for the march, the execution of the scoop-up, and the immediate aftermath. In some respects the new testimony confuses rather than clarifies. For example, instead of one dead body allegedly with nail bombs, the soldiers now speak of three. Although these could all be one and the same incident, it is not clear and will take time for the new inquiry to unravel. In another incident, a witness in a second statement sees a soldier fire into a Pig containing three dead bodies, an event that was not mentioned in the first statement. During the relatively short life of the Saville Inquiry, several key official documents (MoD, Cabinet Office, NIO) have been declassified, adding significantly to an understanding of the military strategy behind the use of paratroopers in Derry and the part played by the British and Stormont governments. We have combined original archive material with new military, government and Saville material. We have included material from interviews taken from IRA members. Following the ruling on anonymity for the soldiers we have excluded their names although many are now known (we have named those senior officers already named), and we have also excluded the names of IRA members who told us in 1972 what the IRA did on that day. In each chapter we have identified the key contested issues which the Saville Inquiry will face. As our book went to press, Saville had not released its statements from the soldiers who fired on that day, nor those from the key government officials and military officers. We requested interviews with the following: Sir Edward Heath, Lord Hailsham, Field Marshal Lord Carver, General Sir Robert Ford, Major General Pat MacLellan, General Sir Frank Kitson and Chief Superintendent Frank Lagan. All declined to speak to us in advance of giving testimony to Saville.

X New evidence from Saville — the testimony of Danny Craig — raises the issue of whether there were nail bombs in the hands of civilians in Glenfada Park. As we wrote in our original Insight article, there is a good selection of photographs in the Insight archive, plus eyewitness testimony, that permits the placing with some confidence of the bodies of Willie McKinney and Jim Wray. Malachy Coyle’s statement to the Saville Inquiry is additional testimony to Wray’s last moments. The issue of Private H’s 19 bullets through a bathroom window is still open.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||