Chapter 14 'A Defining Moment' from

|

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | 7 |

| PREFACE | 9 |

| 1 Childhood in Belleek | 11 |

| 2 Not the Happiest Years | 29 |

| 3 Irish College, Rome | 40 |

| 4 Great Sadness - Great Happiness | 63 |

| 5 Curacy in a Border Town | 73 |

| 6 Hi Mister! Are You a Priest? | 93 |

| 7 The Daily Pastoral Round | 103 |

| 8 No Business Like Show Business | 113 |

| 9 Seeds of Unrest | 119 |

| 10 Marches and Protests | 129 |

| 11 Burntollet and Its Aftermath | 136 |

| 12 Mayhem | 147 |

| 13 All Kinds of Everything | 162 |

| 14 A Defining Moment | 187 |

| 15 Widgery - The Second Atrocity | 201 |

| 16 Gethsemane | 214 |

| 17 To Dublin and Back | 228 |

| 'Priesthood' by Karl Rahner, SJ | 251 |

| INDEX | 254 |

Chapter 14

'A Defining Moment'

Returning to Derry after the short break, I decided to revive a few of my earlier interests. I offered to produce a play for the '71 Players. The three-act play I chose was The Righteous Are Bold, a melodrama by the playwright, Frank Carney, and set in the West of Ireland. I cast the play and began rehearsals in mid-January. I also got cracking on the Long Kesh concert party, but a letter to me from the Secretary of the Ministry of Home Affairs in Stormont, dated 24 January 1972 put paid to that project. The letter read:

I refer to your recent letter about the possibility of entertaining internees at the Internment Centre, Long Kesh.

You may be aware that a number of concerts were staged at Long Kesh at the end of last year. However, it was never intended that this arrangement would extend beyond the Christmas season and I regret that it is not now possible to allow 'live' shows to be staged at the Internment Centre.

Permission was refused. The refusal was not altogether a surprise.

Rioting, gunfire, arson and bombing punctuated early January 1972. Resentment against internment continued and deepened in the Catholic community. On Saturday, 22 January, there was a march on Magilligan beach near Derry. All marches were illegal and banned by the Stormont Government at this time. It was a protest against internment in general and the opening of a new internment camp in Magilligan in particular. It was one of a series of similar marches around the North. There was a heated confrontation between protesters and members of the Parachute Regiment. Such a confrontation on a beach was rather incongruous in the middle of January. Although not apparent at the time, it was a hint of the disaster that lay ahead. NICRA had planned a protest march against internment in Derry the following Sunday, 30 January.

The week before the march on Sunday, 30 January, was a bad week. Loyalists threatened to attack or disrupt the march. On the Thursday of that week, two RUC officers were cruelly murdered in a fierce IRA ambush just up the street from the cathedral. Police and Army saturated our entire area for many hours after the ambush. The atmosphere became very ugly and frightening. I was deeply disturbed by the fact that some people, who should have known better, were jubilant after the deaths of the two policemen. People were becoming more and more hardened by the constant violence. We waited for the weekend with a little foreboding, but no more than usual on the eve of a big march. We felt that we had been through all this before. My main concern was to have a good rehearsal of the play with my cast late on Sunday evening when, hopefully, all would be over.

Sunday, 30 January 1972, was a cold and crisp day, a beautiful invigorating winter's day with a clear blue sky. I assisted at the various morning Masses in the cathedral, did door duty, helped at Communion and spoke with people as they came and went. On an average Sunday at that time, five or six thousand people attended Mass in St Eugene's. People talked about the usual things. Some mentioned the shooting of the police officers. Some talked about the weather, some talked about football and a few, very few, talked about that afternoon's march. It was not foremost in the minds of people. I was scheduled as celebrant for the 12 noon Mass. After the Communion ended and I was preparing for the concluding prayers of the Mass, Father Bennie O'Neill, administrator of the cathedral, came to me on the altar. He told me that, within the previous fifteen minutes, large numbers of heavily armed paratroopers had moved into position around the cathedral and into all the adjoining streets. He asked me to appeal to the people to remain calm and to make their way home without getting into any confrontation with these new arrivals. I made the appeal, as requested.

We had our Sunday lunch together as usual. At this time, due to the arrival of the paratroopers, we were becoming a little worried about confrontations at the march. Other priests, who had seen them, described the paratroopers as being gung-ho and quite aggressive. However, we were not unduly worried. Around 2.15 p.m., I left the parochial house to go to Abbey Street, to take a funeral to the City Cemetery. A lady called Mrs Organ had died. I had attended her during her illness. The funeral left Abbey Street about 2.30 and I led the funeral cortège, which made its way to the City Cemetery, which lay between the Bogside and Creggan. By this time, large numbers of people were making their way to join the march. The march was to set out from Creggan at three o'clock. The paratroopers were less visible than they had been earlier. In fact, I cannot recall seeing any soldiers on the way to the cemetery. I conducted the burial service, spent some time with the family at the graveside and then the undertaker drove me back to the parochial house some time between 3 and 3.30 p.m. The head of the Civil Rights March then was proceeding down Creggan Street from Lone Moor Road, past the Cathedral on its way to William Street.

When I returned from the funeral, I decided to go to the Rossville Street area to ensure that the elderly and housebound were alright. This was my usual practice when there was a possibility of serious confrontation or of CS Gas being used. On my way down William Street, as I walked along with some of those in the march, my attention was drawn to some marchers ahead who were jeering and looking to their left. I looked in that direction and saw a soldier with a rifle on a wall or roof at the rear of Great James Street Presbyterian church across the waste ground where Richardson's Shirt Factory used to be. I had never seen a soldier in that particular location before. At the corner of William Street and Rossville Street, most of the crowd turned right to go over Rossville Street; some people proceeded further down William Street. I went on past the junction of William Street and Rossville Street. The crowd had built up. The Army had erected a barrier further down William Street at the bend in the street, between the junction with Chamberlain Street and Waterloo Place. There was a crowd backed up some distance from the barricade. I went to the doorway of Porter's radio and television shop and observed the situation for a few moments. I was on the point of going back to Rossville Street when there was an outbreak of jeering and catcalling. Originally it was good humoured, and then, after a short time, missiles were thrown by some members of the crowd in the direction of the Army barrier. The firing of the missiles intensified and the Army responded with water-cannon and CS gas. The people nearest the barrier tried to get away and there was a moment of panic as people at the back of the crowd tried to push forward; but then the crowd thinned and dispersed, apart from a hard core of rioters. Some of the crowd eventually dispersed along Chamberlain Street, some went through an alley at Macari's fish-and-chip shop, and the biggest majority went across Rossville Street with the main body of the march.

I then moved to

Rossville Street, and stopped between the junctions with Pilot's Row

and Eden Place. When I reached this point, I noticed a fair-haired man

with glasses, whom I later knew to be Kevin McCorry, a leader of the

Civil Rights Movement. He was using a loud hailer asking the crowd to

leave the William Street area and go to Free Derry Corner where there

was going to be a meeting. Most of the crowd paid attention to this

and the crowd gradually started to disperse, most of them moving towards

Free Derry Corner.

I decided to stay where I was so that I could be available, if required,

to the elderly people living in nearby Kells Walk and Glenfada Park.

I did not intend going to the meeting. There was still some CS gas being

fired and a greatly reduced number of young people were throwing stones

at the Army barriers in Little James Street and William Street. I spoke

with a number of people who were passing by. Some were discussing the

march, expressing relief that it had passed off relatively peacefully.

I spoke to Stephen McGonagle, former vice-chairman of the Derry Development

Commission, and subsequently Ombudsman for Northern Ireland. Then I

met Patrick Duffy (known to local people as 'Barman'), a Civil Rights

steward, a very much-respected man in the Bogside area. I was concerned

about some of the young people who were behaving rather suspiciously

at the rear of some shops in William Street, adjacent to the waste ground.

These shopkeepers had suffered a lot of vandalism and destruction at

that time. I asked 'Barman' to keep an eye on them lest they do any

further damage to this property.

Some time after this, I heard two or three shots ring out. I knew that

these were gunshots and not rubber bullets, because the report of a

live round is much sharper and louder than the report of a gas grenade

or rubber bullet. These sounded to me like the sharp cracks of a rifle.

With others, I moved close to the wall at the end of Kells Walk to take

cover. There were two or three shots. They were single shots, with a

momentary pause between each. I formed the impression that they came

from the Great James Street area. Certainly most of the people present

looked in that direction and took cover as if the gunfire was coming

from there. There was a moment of panic and then things settled down

again. Shortly after this, a person came rushing up to me and said to

me that two men had been shot in the vicinity of the Grandstand Bar,

which was located in William Street. I moved into the passage between

Kells Walk and Colmcille Court to make my way to the scene, and I met

people who told me that two priests were already on the scene attending

to the two casualties. They said that the casualties were being taken

to hospital. One of these priests was Father Joe Carolan. I then made

my way back to my original position in Rossville Street.

On my way, I spoke

to some of the residents in Kells Walk. They opened their windows and

spoke to me. They were concerned about the gunfire. I assured them that

all was well and that there was nothing to fear. Within my sight, there

were still a number of people in the vicinity, stragglers at the end

of the march, people chatting, and a number of young people were still

throwing stones sporadically at the Army. But most of the people had,

by this time, made their way or were making their way to Free Derry

Corner.

Some minutes after I returned to Rossville Street, the revving up of

engines, motor engines, drew my attention. I looked across towards Little

James Street. I noticed there or four Saracen armoured cars moving towards

me at increasing speed, followed by soldiers on foot. I observed them

for a few moments. Simultaneously everyone in the area began to run

in the opposite direction - away from William Street and across Rossville

Street towards Free Derry Corner. I ran with the others but veered to

my left towards the courtyard of Rossville Flats. I was running and,

like most of the crowd, looking back every few moments, to see if the

armoured cars and soldiers were still coming. They kept coming. Around

this time, I remember seeing someone thrown in the air by a Saracen.

This happened somewhere on the waste ground to the east of Rossville

Street.

As I was entering the courtyard, I noticed a young boy running beside

me. I was running and he was running and, like me, looking back from

time to time. He caught my attention because he was smiling or laughing.

I do not know whether he was amused at my ungainly running or exhilarated

by nervous excitement. He seemed about 16 or 17. I did not see anything

in his hands. I didn't know his name then, but I later learned that

his name was Jackie Duddy. When we reached the centre of the courtyard,

I heard a shot and simultaneously this young boy, just beside me, gasped

or groaned loudly. This was the first shot that I had heard since the

two or three shots I had heard some time earlier in the afternoon. I

glanced around and the young boy just fell on his face. He fell in the

middle of the courtyard, in an area, which was marked out in parallel

rectangles for car parking. My first impression was that he had been

hit by a rubber bullet. That may be because the noise of the shot had

been masked by the general din and chaos, which prevailed at that time.

The shot seemed to come from behind us, from the area in which the Saracens

were located. I thought initially, that the shot had been the report

of a rubber bullet gun; I could not imagine that he had been struck

by a live round.

I ran on still looking back. Some or all of the Saracens were still progressing towards the Rossville Flats. I looked at the passageway between Blocks One and Two of the Flats, the exit I had intended and hoped to use to escape from the courtyard. It was jammed by a mass of panic-stricken and frightened people. A woman was screaming. The air was filled with the sound of panic and fear. With considerable apprehension, I realised that there was no way out of the courtyard. Then there was a burst of gunfire that caused terror. I could not be sure whether they were shots from several weapons simultaneously or from one weapon. These were live rounds - there was no doubt any more. I then sought cover behind a low wall at the rear of the garages at the foot of Block Two of the Rossville Flats. There were about twenty or thirty people already taking cover there. There was no room for anyone else. So I threw myself on the ground at the end of the wall. All the shots seemed to come from the location of the Saracen armoured cars between Pilot's Row and the courtyard of the Flats. During this period of time, I was not aware of any shots being fired towards the soldiers' position or of shots being fired from the upper floors of the Flats or from anywhere else.

During a lull in the firing, I looked over from where I was lying and saw Jackie still lying out in the middle of the car park where he had fallen. He was, at this time, lying on his back with his head towards me. This puzzled me. I had distinctly remembered him falling on his face. I thought that, perhaps, he had managed to turn himself over. I subsequently learned that Willie Barber, who was running behind me, had turned him over. I then decided to make my way out to him. I took a handkerchief from my pocket and waved it for a few moments and then I got up in a crouched position and I went to the boy. I knelt beside him. There was a substantial amount of blood oozing from his shirt; I think it was just inside the arm, on the right or left side, I cannot remember which. I put my handkerchief inside the shirt to try and staunch the bleeding. Then a young member of the Knights of Malta, Charles Glenn, suddenly appeared on the other side of this boy. He immediately set about treating the wound. I felt that I should administer the last rites to the boy and I anointed him. The gunfire started again around this time. We got as close to the ground as we could. Then there was another lull; a group of two or three people came out and stood behind us. They offered help. We asked them to go back - we felt that we were safer on our own - so they went back.

After some time, a tall young man with long, fair hair dashed past us. Just in front of us, a little to our right, he began dancing up and down and screaming at the soldiers. I thought that he was shouting, 'Shoot me, shoot me', or something of that nature. He had his hands raised over his head, waving them around. He had nothing in his hands. He appeared to be hysterical. We shouted at him to clear off and then a soldier stepped out from the gable end of Block One of the Rossville Flats, went down on one knee, took aim and fired at him. The young man staggered and then he started running around crazily for a few moments. I do not know exactly where he went to or whether he fell but I did not see him afterwards. I knew, however, that he had been struck by a shot from that soldier whom I saw taking deliberate aim. The soldier stepped out from the corner of the Rossville Flats, near the access door. I subsequently came to know that this man's name was Michael Bridge. He was hit in the leg, and fortunately, survived. It was the one occasion in my lifetime when I witnessed one human being deliberately shoot another human being, both of them being close to me and within my vision. One was armed, the other was unarmed. This occurred as I was kneeling beside another young boy whose life-blood was seeping away. It was a terrifying and shocking experience.

Shortly after this, two other men, William Barber and Liam Bradley joined us. They took up positions beside the young injured man whom we were attending. There was sporadic gunfire at this stage - bursts of automatic gunfire, from time to time, interspersed with single shots. Jackie was rapidly losing blood and there was obviously great need to get him to hospital as soon as possible. At one stage, a woman nervously appeared at the window of one of the lower flats and a member of our group shouted to her 'Have you a phone, have you a phone?' But she shook her head. Few people in the Rossville Flats had phones. The other men in the group then said that if I was prepared to go before them with a handkerchief, they would be prepared to carry this young man somewhere where he could receive the necessary medical attention. There was a discussion as to whether we should carry him back towards the front of Rossville Flats or carry him through the Army lines. Willie Barber was a telephone engineer. He said that there was no point in bringing him back to the flats because the telephone kiosk there was out of order. We reached the conclusion that we had a better chance of calling an ambulance if we carried him to Harvey Street or Waterloo Street. We decided to do that. We desperately needed an ambulance.

Just as we were about to get up and move, a man moved along the gable wall of the last house in Chamberlain Street, about twenty yards from us. The house backed on to waste ground. He suddenly appeared at the corner of this house and moved cautiously along the gable. His movements were rather suspicious and suddenly he produced a gun from his jacket. It was a small gun, a handgun, and he fired two or three shots around the corner at the soldiers. The soldiers in this area facing the flats were stepping out in the open from time to time. I cannot recall the soldiers reacting or firing in his direction. They did not seem to be aware of the gunman. We screamed at the gunman to go away because we were frightened that the soldiers might think the fire was coming from where we were located. He looked at us and then he just drifted away across or into the mouth of Chamberlain Street. I did not see him after that nor, to the best of my knowledge, did I see him before then. I did not recognise him as someone I knew.

At this point we decided to make a dash for it. We got up first of all from our knees and I waved the handkerchief, which, by now, was heavily bloodstained. I went in front and the men behind me carried Jackie Duddy. We made our way into Chamberlain Street, along that street and then turned into Harvey Street. Soldiers challenged us at this point and we saw the BBC News camera crew with cameraman, Cyril Cave and reporter John Bierman. We then proceeded to the corner of Waterloo Street and Harvey Street. At this point Willie Barber took off his coat, spread it on the ground, and we laid Jackie Duddy on it. At that time he appeared to be dead. After being asked by us, a woman called Mrs McCloskey, who, as far as I recall, resided in the street, phoned for an ambulance. Then a patrol of soldiers appeared in Waterloo Street and told us to clear off and I asked the people to calm down and kneel down and offer a prayer. The soldiers moved away. I remember one of the women screaming down the street after them shouting, 'He's only a child and you've killed him.'

We waited until the ambulance arrived. I am not sure how long it took. It wasn't very long. Jackie Duddy's body was brought to the hospital. Mrs McHugh, a resident, kindly offered me a cup of tea. I quickly took a few sips and then I made my way via Fahan Street and Joseph Place to the area of Block Two of the Rossville Flats in front of the shops. I was thunderstruck by the scene that met my eyes. Until then, I had no conception of the scale of the horror. I quickly realised that I had witnessed merely a small part of the overall picture. There were dead and dying and wounded everywhere. I administered the last rites to many of them. I don't know how many. There was no firing at this time. Then an ambulance came and parked on Rossville Street at the corner of the Rossville Flats, near the main entrance. An attempt was made to get bodies out from this area towards the ambulance - and then there was more firing. Father Tony Mulvey went forward, waving a handkerchief, and facing towards the soldiers, in an effort to get them to cease firing. I could not see the soldiers from my position, but this firing was coming from further over Rossville Street.

Then John Bierman of the BBC asked me to do a television interview. We were standing near the telephone kiosk at the southern end of Block One of the Rossville Flats preparing for the interview and suddenly a single shot rang out and we had to dive for cover. I eventually did the television interview beside a doorway on the Joseph Place side of Flat Block Two. In that interview, I described what I had seen as murder. When the interview was completed I stayed around and tried to calm people down. A great number of people were suffering and greatly traumatised by their experiences and all were deeply distressed. People gradually started coming out of their houses and out of the Rossville Flats. Many people had sought shelter in houses in the area. When the wounded and the bodies of those who had died had been taken to the hospital, and the situation had settled somewhat, I eventually headed back towards the parochial house, via the Bogside and Little Diamond where I was stopped and challenged by a patrol of soldiers. I showed them my hands, which were completely covered in blood. I asked what on earth possessed them to do what they did. They did not insist in going through with the search. I arrived at my house. I was angry, frustrated and distraught.

After I got back

to the parochial house, the enormity of what I had just witnessed crashed

in on me. The kitchen was the place where we all gathered. I wept profusely.

Maggie Doherty, our housekeeper, comforted me. She was the mother figure

to us all on the many occasions of turmoil or grief. Other people and

other priests arrived. Not much was said. Everyone was stunned into

silence. Bishop Farren was in and out, asking us what had happened,

distressed, bemused, incredulous and confused like all of us. He had

been bishop of Derry for more than thirty years, but nothing could have

prepared him for this.

I decided to call the Superintendent of the RUC in Derry at that time.

Patrick McCullagh had been a contemporary of mine at St Columb's College.

I rang him and asked what on earth had happened or why this terrible

thing had occurred. He said that he was under the impression that it

was only a minor disturbance, that his latest reports were that only

two people had been injured and several arrested. I told him that I

had seen a number of dead bodies and that many had been seriously injured.

He expressed disbelief at this but said that he would check it out.

He rang me some time later to tell me that the latest report was that

eleven dead bodies had been admitted to Altnagelvin Hospital.

By six o'clock, it was clear that at least thirteen people had died and many were seriously injured and large numbers had been arrested and held in custody. The parochial house was under siege from worried families. Many people had not returned home after the march. Only a few of the dead bodies had been identified. People came desperately asking us had we seen their son or daughter, had he or she been one of those killed or injured. The RUC and Army, to their added discredit, refused to release the names of those who were in custody. A gesture from the RUC or Army, even at this late stage, would have afforded some degree of relief to desperately worried people. To add to the confusion, there were many contradictory reports about identities coming from Altnagelvin Hospital.

There was Mass in the cathedral at 7.30. I cannot remember who celebrated that Mass, but we all sought the Lord's help in our sadness and shock and despair. Mrs McDaid, mother of Michael McDaid, and some members of her family came to the parochial house seeking news of her son who hadn't returned home. Shortly before she arrived, we had received a full list of the names and addresses of the thirteen dead. Michael's name was not among them. We were able to assure her that he must have been arrested or injured. He would be home. She left the house relieved at this news. A few minutes later, word came through that there had been a mistake - one of the dead had been wrongly identified. A body had been incorrectly identified as the body of young man called Gillespie - it was then identified as the body of Michael McDaid! One of my colleagues had to go to Mrs McDaid and her family and break the awful truth to them. After erroneously building up her hopes, I could not face her myself.

Cardinal William Conway telephoned Bishop Farren and asked to talk with Father Tony Mulvey and me. He had seen the television pictures and he sought a first-hand account before he would make any statement to the media. We spoke to him, at length, from Bishop Farren's study describing what we had seen. He repeatedly asked 'Are you sure of this? Are you absolutely certain of this? You are not exaggerating?' Bishop Farren, now almost eighty years old, was perplexed at how radio stations in New York and other parts of the world already knew about the events that had occurred just down the street in Derry. They were calling him for interviews and comments. I then thought of my mother. I called her briefly and assured her that I was all right. She had seen the television news and had been very worried. She had tried to call on the telephone but could not get through. She was relieved that I was safe.

With other priests, I spent much of that night going around the families of the dead and injured. Some of my colleagues went to the hospital. I decided not to go there. I felt that I could not cope with seeing any more dead bodies. Apparently, there were some very tense and angry scenes there between a heavy RUC and Army presence and many anxious and distressed relatives seeking news of their loved ones. Gradually as the evening and night wore on, those who had been arrested were released and arrived home to the relief of their families. Late that night, the families of the dead and injured were all too aware of the fate of their loved ones. The entire community was consumed with shock and grief.

First-hand exposure to the multiple violent deaths of innocent unarmed people on the street leaves a lasting impression. The dreadful events of that Sunday afternoon constituted a defining moment for me and for many others. It was the day when I lost any romantic notions or ambivalence that I may have had about the morality of the use of arms as a means of resolving our political problems. Ever since my experience on that terrible day, I could no longer find any justification for the use of armed aggression by any faction in the North. I have to confess that this was a conclusion reached on emotional as much as moral grounds. Despite the propaganda, there is little that is glorious about armed conflict. Whatever the mythology, it is in reality a nasty, vicious and destructive business. It is my experience that it brutalises both those who participate in it and the society in which the warriors engage in their deadly combat. There may be some circumstances where and when armed conflict is necessary and constitutes the only possible way forward. In such situations, it may be morally justified. It is my conviction that such circumstances did not exist in our situation.

However, these murders, because that is what they were, had a quite different impact and influence on others, particularly younger people. Countless young people were motivated by the events of that day to become actively involved in armed struggle and, as a direct result, joined the Provisional IRA. Many former paramilitary members have gone on record stating that they first became actively involved in the wake of that Sunday. I am not at all sure about how I would have reacted, had I been a teenager and witnessed those same events.

Bloody Sunday cast a long and enduring shadow.

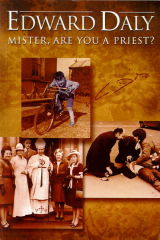

This extract is taken from Mister, are you a priest? by Edward Daly.

To order this book on-line

If you live in North America or would like to send a copy of this book to someone living in the Americas, click here for secure on-line ordering.

For all other orders, click here.

To order this book by telephone In North America, call: International Specialized Book Services (Portland, Oregon)

All other orders (Ireland, Europe and rest of the world), call: For additional information about this book contact the publisher :info@four-courts-press.ie.

toll-free, 800-944-6190

Gill & Macmillan Distribution (Dublin, Ireland) 00 353 1 - 500 9555

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||