'The Battle of Bogside: The Politics of Violence in Northern Ireland' by Russell Stetler (1970)[Key_Events] Key_Issues] [Conflict_Background] CIVIL RIGHTS: [Menu] [Reading] [Summary] [Background] [Chronology] [Main_Pages] [Newspaper_Articles] [Sources] The following chapter has been contributed by the author Russell Stetler. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the members of the CAIN Project. The CAIN Project would welcome other material which meets our guidelines for contributions.

Hardback 212pp 7220 0614 4 [Out of Print]

This chapter is copyright Russell Stetler and is included on the CAIN site by permission of the author. You may not edit, adapt, or redistribute changed versions of this for other than your personal use without the express permission of the author. Redistribution for commercial purposes is not permitted.

The Battle

of Bogside

The Politics of Violence

Russell Stetler, 1970 Sheed and Ward London and Sydney

Contents Acknowledgements Introduction 1 The Setting 2 Political Antecedents 3 August 4 Bogside Gassed 5 A Comment on the Himsworth Report 6 Conclusions: some thoughts about counter-insurgency Appendix: the development and use of cs Bibliography Sources

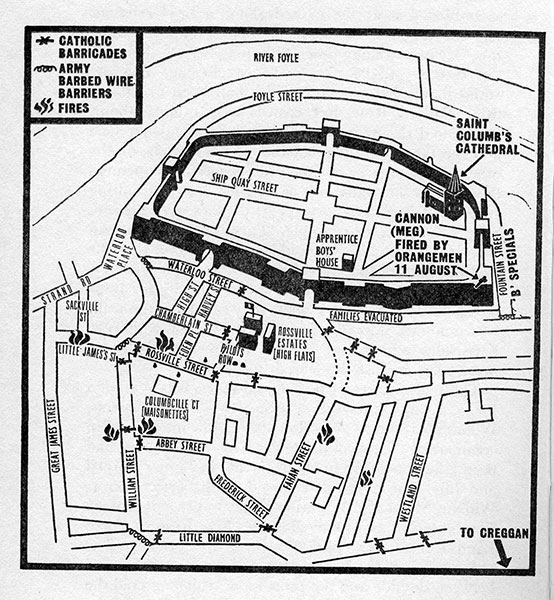

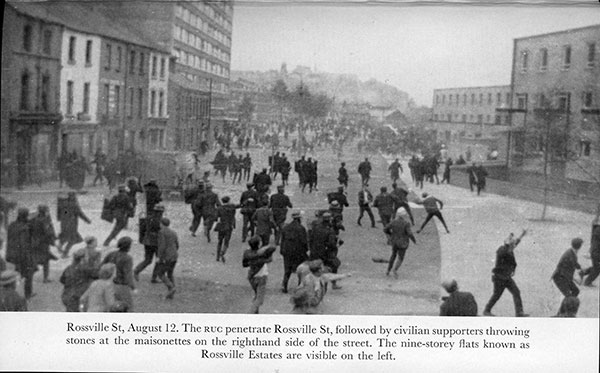

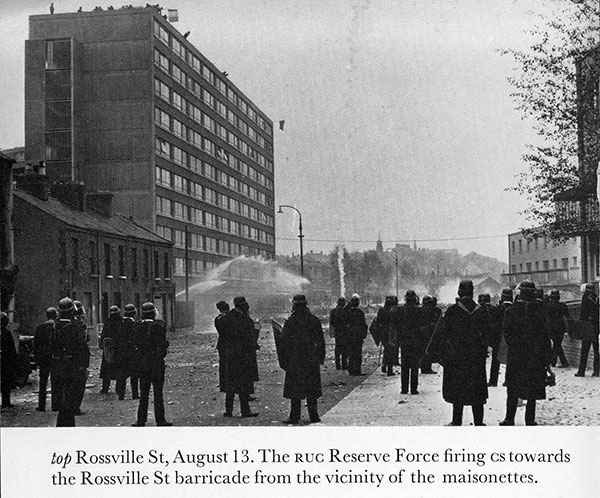

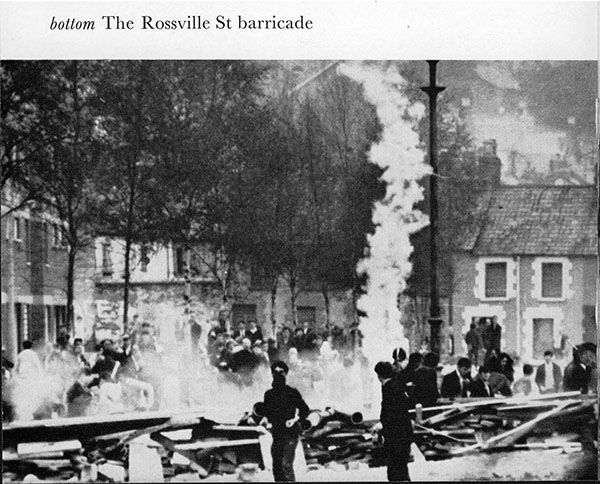

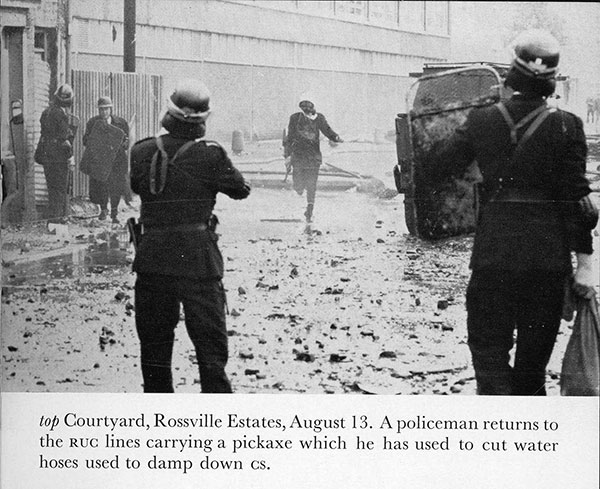

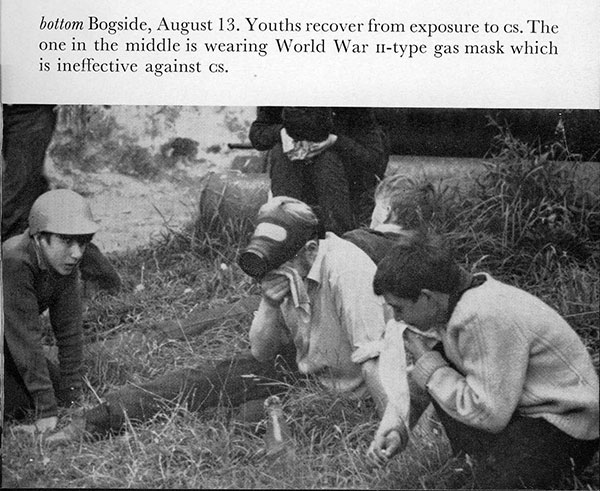

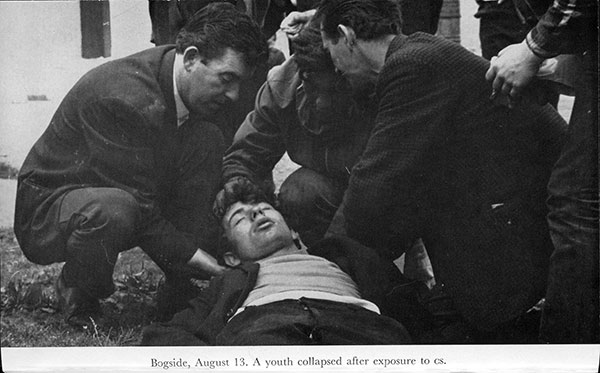

3: August For the Protestant population of Northern Ireland, Derry is an ancient symbol of an embattled people, besieged by Papists and threatened by treason from within. The siege of Derry City in 1689 provides the scenario of the drama which Protestant extremists find re-enacted in most recent times, as disloyal elements in Stormont Castle seem on the brink of betraying loyal Ulster to Rome. In 1689, an army under the Catholic King James II marched across Ulster, and large numbers of Protestants fled before them. The Orangemen of today quote approvingly the description by Lord Macaulay: All Lisburn fled to Antrim; and, as the foe drew nearer, all Lisburn and Antrim together came pouring into Londonderry. Thirty thousand Protestants, of both sexes and of every age, were crowded behind the bulwarks of the City of Refuge. There, at length, on the verge of the ocean, hunted to the last asylum, and baited into a mood in which men may be destroyed but will not easily be subjugated, the imperial race turned desperately to bay.1 The governor of the city, Lundy, was literally loyal to the crown. Since the Catholic King James was the legitimate ruler, he intended to deliver the city to him. Ever since, his name has been a synonym for traitor, and Protestants do not hesitate to apply it to any politician whose ‘loyalty’ to Britain fails to conform to more sectarian interpretations. Derry City was ‘saved’ from the traitor Lundy by thirteen young Apprentice Boys who closed its gates when the Catholic armies were first sighted on the horizon. The slogan of the ensuing siege, ‘No Surrender’, has been a battle-cry of Ulster Protestants ever since. Revived in the twentieth century during the Ulster crisis, it continues to evoke great emotion today, scrawled on walls throughout the province. It recalls confrontation, heroism and victory. The anniversary of this victory, the lifting of the siege, is celebrated on August 12 in Derry. For the city’s Catholic majority, the event hardly merits celebration or enthusiasm, but the annual march of the Apprentice Boys commemorative organisation had come to be accepted like any other ritual. Many factories close down in any event at this time, so a substantial number of Catholics are normally away on holiday when the march occurs. Catholic shopkeepers and tradesmen could hardly object to the material benefits of the tourist attraction. The processionists come from all over the Six Counties, often bringing their wives and families with them. They are not literally apprentices, of course, but Protestant men of all ages who assemble to commemorate the name and example of their young heroes of 1689. In the procession, they wear bowler hats and Orange sashes. Tens of thousands come to Derry for the celebration. The trains are crowded, and the roads congested. On the night of the eleventh, the festivities commence with ceremonial bonfires (Lundy is burned in effigy on the city’s walls overlooking Bogside), and the ritual firing of the cannon ‘Roaring Meg’ is simulated. The next day religious services and the procession form the main activities. In the recent past, the event had come to pass peacefully enough. If the Catholics did not participate in the merriment, they had at least been passively tolerant. Protestant behaviour had become fairly restrained. But a new situation was inevitable in 1969. Among those who came to Derry for the twelfth was a new element: some two hundred journalists from around the world, including several specialists in civil disorders and guerrilla warfare. As the Times correspondent later told the Scarman Tribunal, ‘I was here because I knew there was a fair chance that a riot would erupt in the city on the twelfth.’ The festivities began as usual on the evening of the eleventh. Bonfires were lit in the Protestant enclave of Fountain Street, just inside the City’s walls at the Butcher’s Gate entrance to Bogside. Pressmen mingled in the crowds that were gathering, and Lieutenant Robbin, the intelligence officer, was on hand in civilian clothes as an observer. The firing of Roaring Meg went off according to schedule, and there were tense moments as Protestant and Catholic crowds within the walled city - occasionally drunk and often carrying bottles - confronted one another. Some windows were smashed, and some taunts exchanged. But the eve of the parade managed to pass without serious incident. In the early afternoon of the twelfth the marchers assembled first at the cathedral for a brief religious service. When it finished, slightly behind schedule, they began marching down Shipquay Street, alongside the section of the city walls overlooking Bogside. Immediately below, the families had been evacuated from Nailor’s Row, but crowds were milling about. Occasional shouts were exchanged between marchers and spectators, on the one hand, and Bogsiders, on the other. Some marchers and onlookers threw pennies down from the walls, not as missiles, but as insulting symbols of Bogside’s poverty. As pennies were thrown, people shouted, for example, ‘There you are, you can earn it like we can.’ It should be emphasised that the vast majority of the marchers were strangers to Derry, and Bogside was an object of great curiosity for these outsiders. In some ways, what they saw from the walls was ominous. Already there were signs of activity - barricades and petrol bombs in the making - as a precaution against the feared ‘invasion’. The main centre of tension, however, was Waterloo Place, a large intersection where two Bogside streets, William Street and Waterloo Street, flow into the main commercial district of the town. This general area had been a focal point in previous rioting in January, April and July. The police had placed crush barriers across William Street and Waterloo Street to prevent anyone from entering or leaving Bogside. Five Reserve Force Land Rovers were parked around the public toilets at the centre of the intersection, to form a sort of screen between Bogside and the procession, which entered the area at the far side of the intersection, in front of the large Wellworth’s store, before turning sharply down the Foyle Road, away from Bogside and out of sight of any observers behind the crush barriers. Although these barriers are light constructions of tubular steel (designed mainly for royal processions and football matches), they were very seriously maintained by the police that afternoon. It was assumed on both sides that this would be the major potential trouble spot. Around two dozen civil rights stewards were on hand there. Colonel Todd went there directly, in civilian clothes, when he arrived in Derry at 2.00 that afternoon. By that time there was a crowd of three to four hundred persons behind the barriers. From the RUC, four sergeants and twenty-four constables were on hand. Full riot equipment - helmets, shields, batons, etc. - was stored in the police vehicles. A crowd of spectators who were sympathetic to the parade had also gathered, including many of the wives of the processionists. Also concentrated here was the enormous press entourage, including several television cameras. There is no question that the Catholic crowd behind the crush barriers was hostile to the march. They resented what they regarded as official hypocrisy in banning a series of civil rights marches while declining to interfere with a Protestant march. The familiar insults implicit in the sectarian tunes to which the Apprentice Boys marched served only to inflame this feeling. Above all, the Bogsiders were frightened at the prospect that their community would be invaded by sectarian gangs and/or the RUC. The crowd certainly included curious spectators, seeking a glimpse of the parade, and a fair number of shoppers, since William Street is a commercial Street and Waterloo Place the normal junction where Bogside residents enter the city to do their shopping. There was also an element of more passive persons, worried about what might develop but unsure as to what their own role would or should be. From the angry youths in the crowd, often just teenage boys, an occasional stone would be thrown. The priests and unofficial stewards tried with some difficulty to restrain those who were throwing stones. But their role was unenviable. Where it had been possible to find up to 250 civil rights stewards on past occasions, by August 12 it was extremely difficult to find any. They had become subjected to increasing abuse from their own side in what John Hume termed their ‘justifiable anger’ at Catholic stewards doing the job of the RUC. The initial shouts exchanged from one side of the barrier to the other are said to have been relatively good humoured, but the situation changed rapidly for the worse. The stones appear to have been little more than a nuisance to the marchers, who were nearly out of range. Any marcher who sought to break ranks to return a stone or even to hurl invective was quickly stewarded back into the ranks. Some sympathetic spectators of the march were more affected, but the police clearly bore the brunt of the stoning. Positioned in a line between the parade and the crush barriers, only twenty-five to thirty yards from the Catholic crowd, their line was in a very vulnerable spot. They suffered their first casualties at about 3.20 p.m., and within five minutes the first police reinforcements had arrived. The RUC made no effort to arrest the stone throwers or to disperse the Bogside crowd; nor did they return any stones at this time. Their exemplary discipline on this occasion - in marked contrast to their conduct in October, January, April and July - is attributed by many commentators to the presence of television and press. The Royal Ulster Constabulary were evidently aware of the extent to which their image had been tarnished by hostile press reports in the past. Although the highest ranking police officials who testified before the Scarman Tribunal categorically denied that the presence of cameras and journalists had had any affect on police reaction to the stoning, there was greater candour in the lower ranks when they simply admitted being conscious of the television cameras around them. As one District Inspector put it, these were not the only factors influencing police conduct, but they couldn’t help being aware of them. Lieutenant Robbin likewise observed that the police were probably more self-conscious under the eye of television, as most people would be. The police were also conscious of the effect upon unruly Protestant elements of any initiative which they might take against stone throwers from Bogside. As District Inspector Armstrong noted in his testimony, the police could not move on the William Street crowd on the afternoon of the twelfth without being followed by Protestants. The barrage of stones grew steadily heavier, despite the efforts of civil rights stewards to discourage what they took to be provocative, hooligan activity. The Protestant crowds became increasingly restive as well. Both District Inspector Armstrong and Robin Chichester-Clark (Westminster MP for Londonderry and brother of the Northern Ireland Prime Minister) spoke to the crowd through loud-hailers, urging them to move back up Shipquay St out of sight of the William Street crowd. Predictably, this advice affected some but not all of the crowd, and the more militant Paisleyite elements remained in the area. The parade itself ended after a couple of hours and dispersed in an orderly fashion. By late afternoon, many of the Apprentice Boys’ coaches were already leaving Derry. At Waterloo Place, the police line held until much of the Protestant crowd had dispersed up Magazine Street, but by then the crowd on William Street was out of the stewards’ control. Both John Hume and Ivan Cooper had been struck by stones, and another Bogside steward, Alderman Hegarty, had fallen to the ground unconscious. Not far away, an even more tense situation was developing fast. At the junction of Sackville Street and Little James Street there was a similar confrontation between Bogsiders on one side of a crush barrier and RUC on the other. No television cameras were present, and the police were less restrained in their response to stones. The Catholic side also escalated the violence quickly. At 3.25 p.m. the first petrol bomb was thrown here. Behind both the William Street and Little James Street crowds another barricade was being built at the corner of William Street and Rossville Street. According to one journalist’s account, more than two hundred people were engaged in this activity. Throughout the afternoon and early evening these two ominous points of confrontation grew worse. The police saw their primary task as one of containment: they feared the Bogside crowds were riotous and aggressive and that they would be inclined to surge into the commercial areas of Derry on a rampage of looting and destruction if they were not held back. Their secondary task, at least according to their own account, was to ensure that no Paisleyite gangs would enter Bogside for similar riotous purposes. The degree to which this latter plan was operative is disputed, in the light of the evident support which Paisleyite youths rendered to the police at various times. But it is clear that at least at early stages senior police officers were remonstrative towards militant Paisleyite elements, even if they made no actual attempts at arrests. To grasp the apparent absurdity of much of the battle which followed, we must understand the fundamental bind inherent in the strategic thinking of both sides throughout the coming three days. The police apparently believed that they had to contain a riotous mob while many independent observers (including many journalists who mingled freely among Catholics on the barricades) insist that the Bogsiders never had any such intention and could in any event have overwhelmed the police numerically at virtually any time if their object had in fact been to leave Bogside and loot the town. On the other hand, the majority of the Catholics saw themselves as defending their homes and families against an imminent sectarian attack led by the police. This conviction, arising from the recent experiences of police incursions, was deeply held. It was months since normal RUC foot patrols had ventured into Bogside. The Catholics feared that the police would seize this opportunity to reassert their writ in Bogside, since their total absence from the area was now causing them embarrassment in many quarters. Whether the police would have contemplated (or their senior officers condoned) such an action on this particular occasion, in the presence of an international legion of journalists, can only be the subject of speculation. There is much ground for believing that responsible police officials were under strong pressure from above not to tolerate another brutal incursion into Bogside, which would damage not only the reputation of the Royal Ulster Constabulary but that of the Stormont government itself. The resultant situation can only be described as a vicious circle. Who ‘started’ the trouble on this day becomes irrelevant and unanswerable. Two groups confront one another in an atmosphere of tension, recrimination and abuse. They impute to one another sinister intentions which may be far beyond what is in fact contemplated by either side. (At most, they represent the intentions of only a small minority of the group to which they are imputed.) Each side sees itself as performing a defensive duty and strives to do so with increasing force. Every casualty suffered reinforces the prejudice concerning the attributed intention. There is no means of extricating oneself from the trap. The longer one maintains the game, the more likely it becomes that one’s opponent will be forced or provoked into carrying out the sinister intentions which he initially lacked. At best, there is an equilibrium like that of a medieval battle, in which victory is not measured in movement, but in the pain and terror which one side can inflict on the other. By mid-evening on Tuesday August 12, this seems to have been the state of affairs in Derry. The Bogsiders escalated the conflict in the evening by increasing the pressure of petrol bombs. The police replied by throwing stones in order to keep the Bogsiders out of petrol bomb range. Several RUC inspectors have subsequently testified that they told their men not to return stone throwing. (One, County Inspector Corbett, objected on tactical, rather than moral or professional grounds: he claimed the the police would only be returning ammunition to hooligans with a superior aim.) Nonetheless, many independent observers noted not only that police were throwing stones, but they were often going so far as to gather stones on their riot shields to supply ammunition to the Paisleyite gangs which were supporting them. Some of the Paisleyite youths were armed with strong catapults, with the result that a staggering number of windows at the front of Bogside were broken at an early time, including the tough double-thickness windows in the modern high rise flats along Rossville Street. The police also brought numerous vehicles to the scene to assist operations. Land Rovers, Humber armoured vehicles and conventional tenders were all employed. The RUC pushed down William Street behind a Humber, which had been used to push through the barrier which had divided the two forces until then. By 6.00 the police were positioned for their first assault on the Rossville Street barricade. (Intelligence Officer Robbin has testified that the television crews departed around 5.00 p.m., and that he subsequently saw no effort on the part of RUC officers to stop their men from throwing stones in the attack on the Rossville Street barricade.) The barricade was only five to ten yards in from William Street; it was four to four and a half feet in height, constructed mainly from paving stones and planks, and manned by about two hundred people at this time. The police made a very forceful effort, perhaps in the hope of altering the situation decisively before the sun had set. They moved water cannon into William Street and attempted to extinguish some of the fires started by petrol bombs. They came under heavy attack from Chamberlain Street, which runs parallel to Rossville Street from William Street into the courtyard of the U-shaped block of high flats. The police drove hard into Chamberlain Street and hoped at one point to execute a sort of pincer movement, by moving through the courtyard to Rossville Street with a view to pressuring the barricade from both sides. But as they neared the courtyard, they were deluged with missiles from the balconies of the high flats and were forced to call a halt inside Chamberlain Street, just out of the range of these missiles. The unit which had advanced up Chamberlain Street was eventually ordered back, and as they drew back a group of Bogsiders charged up behind them throwing petrol bombs. By 7.30 the police regarded the situation as grave. They were under heavy pressure on both the William Street and Sackville Street fronts. A direct conflict between Bogside and Paisleyite gangs was feared. Redundant policemen were shifted to the positions which were most under attack, and available manpower was generally redistributed into new concentrations. All available forces were committed at that time. Many had been on duty from 8.30 in the morning, and some of these had arisen hours earlier in order to travel considerable distances from their native counties in order to be on duty in Derry for the parade. At some time after 8.00 a Bogside group broke into the GPO sorting office, removing petrol and a few vehicles. The police then accepted support from local Paisleyites in the Sackville Street area; they deemed this step a necessity in light of their manpower deficiencies. Bogsiders dominated the rooftops and threw petrol bombs from these positions, thereby adding to the pressure which the police were experiencing on the ground. A cruel stalemate persisted. The police could not move on the Rossville Street area without reinforcements. Their men were tiring, and they were suffering casualties at a high rate. By this time, Tom Caldwell, pro-O’Neill Unionist (Independent) MP for Willowfield, who was observing the situation, left to telephone Robert Porter to recommend the use of tear gas. It is not clear whether he did so entirely on his own initiative or at the urging of the police. But as the night wore on, the RUC officers on hand gave increasing consideration to the possibility of using cs. In their minds, cs was a means of compensating for the manpower deficiencies of a force which was outnumbered, exhausted and sustaining injuries heavily. It is clear that the agent should never have been expected to do such a job. The intervention of the British Army was an inevitability in these circumstances. Even at the time, it should have been evident that the police could not meet the manpower needs of the situation as they conceived it. One inspector has estimated that one thousand police would have been needed to stabilise the situation, and such numbers were simply unavailable. In the preceding chapter, we have already discussed how the Minister of Home Affairs and the senior RUC officials altered the policy on the use of cs just three days before the Apprentice Boys’ march. The written instructions containing this new order on cs were only available, in fact, on the morning of August 12, and even then, only in Belfast. That evening Deputy Inspector General Shillington followed developments in Derry from the RUC headquarters in Belfast. He became concerned at the trend of developments and finally proposed to his superior officer, Peacocke, that he should go down to Derry to observe the situation personally. The Inspector General accepted Shillington’s proposal, and in a matter of minutes the RUC’S second-in-command was on the road. He followed the further deterioration of the situation by car radio. While he was on the road, County Inspector Mahon put through a request to the Minister of Home Affairs for authorisation to use cs. A general authorisation was given, and Shillington received a message to this effect while on the road between 10.15 and 10.30 p.m. He arrived in Derry around 11.00 carrying with him the written orders on the conditions for employing cs. At 10.30 County Inspector Mahon sent the head of the Reserve Force, District Inspector Hood, to assess the situation on the ground at the main pressure point in the Sackville Street area. Hood assembled all the Head Constables of the Reserve Force at the junction of Sackville Street and Little James Street between 10.30 and 11.00. They were unanimous in their belief that cs represented the only means of containing the situation. When Shillington reached the control room at Victoria Barracks, Mahon consulted with him and briefed him on the immediate crisis. Shillington then went with Hood and Armstrong, as well as with Colonel Todd (still in civilian clothes), to inspect the situation at Sackville Street. He found what he described as a large riotous crowd of at least four hundred Bogsiders throwing stones and petrol bombs and promptly confirmed that this was a situation in which cs should be used at once. He returned to Victoria Barracks. When he reached the control room, Porter was already on the line awaiting his advice. He recommended the use of cs, and the Minister gave his final authorisation. District Inspector Hood, who was then to be fully in charge of the tactical employment of cs, was instructed to give the appropriate warning over the loudhailer and to use one platoon to discharge the agent. Some warning was then given, but it is not clear precisely what was said. Shillington himself could not hear exactly what was said, nor could he even be sure whether it was Hood who made the announcement. One can assume that in the din of riotous battle such an announcement would reach a modest audience. Harold Jackson, correspondent of the Guardian, who was behind the Catholic barricades at the time, has affirmed that he heard absolutely nothing of the warning, and, like many, if not most, of those around him, was first aware that cs was in use when the first canister landed very near him, at about five minutes before midnight. The first cartridges fired were standard cardboard canisters, based on a Porton design. The cardboard sheath is one and one-half inches in diameter and just over four inches in length. Inside the casing is the metal missile itself. The missile is of slightly smaller diameter and about three inches long. It contains approximately 12.5 grams of Cs, which is mixed with a pyrotechnic charge whose ignition precipitates the dispersal of the agent through four small holes (three around the surface of the cylinder and one at the end). The cardboard cartridges are greyish-green in colour and (in addition to commercial identifying marks and production dates) bear the single red stripe which is the universal symbol indicating a temporary incapacitating agent. They are fired from a Verey -type pistol with an enlarged bore. The cs is dispersed in the form of a fine powder in approximately thirty seconds. Hand grenades, containing four times as much cs, were also introduced soon thereafter, but they were used in much smaller quantities. Once initial approval for the use of the agent had been given, its actual employment in any given tactical situation depended solely on the judgement of the Head Constables of the Reserve Platoons, without further consultation of the District Inspector. The cartridges were fired only by Reserve Force sergeants except in cases where the sergeants became disabled. Hood summarised the considerations involved in the tactical judgements in the following terms, in his testimony to the Scarman Tribunal: They were only to be used when the police were liable to be overrun and again when a suitable target presented itself.That is, if one man came out to throw a petrol bomb, they were not to be used in those circumstances; but if a number of men were using petrol bombs and stones they were to be used to disperse people. In reply to closer questioning, he continued, The situation was to prevent the damage to property from spreading. That was the main consideration because there were fires starting and there were these buildings burning, and the idea was to contain these people and push them back into the Rossville Street area away from the more valuable property. The police claim that the initial use of cs in the Sackville Street area was effective in moving away both Catholic and Paisleyite crowds. According to police accounts, there was a slight wind blowing away from Bogside, such that unmasked civilians behind the police were affected, as well as unmasked police personnel. As District Inspector Armstrong put it, ‘It was very effective and I was delighted to see it.’ The Fire Brigade, which had been unable to enter the area before midnight, now succeeded in moving in to deal to some extent with the existing fires. The police officials were unanimous in their belief that the situation was eminently suitable for employing cs. Shillington has indicated that he asked Colonel Todd’s advice as well, and Todd is said to have told him that the weather conditions were very suitable. On this first day the police had sustained one hundred casualties. They claim that they were frequently deployed in such a way that the Bogsiders were effecting but not sustaining casualties. The situation had clearly reached a point where no baton charge could be contemplated. There had been damage to property, but this does not seem to have resulted from wilful destruction to property so much as it was the inevitable consequence of using petrol bombs in any sort of fighting. The RUC viewed their strategy as a containing action. cs was used to implement this strategy and as a simple means of self-defence. The police took logistical advantage of the control agent’s effects from time to time, but in rather a curious way. At an early time, for example, the RUC used the opportunity presented by the initial use of cs to move a Land Rover rapidly in and out of Rossville Street. But in this case, the sole purpose of the manoeuvre seems to have been to lob cs grenades. By all accounts, such a move could have only very temporary effects. CS was not used as a prelude to police follow-up action to disperse the crowds or to make arrests. Such actions were impossible because of the RUC’s manpower deficiencies. Thus, from the police point of view, cs could reduce the prospect of attack by the Bogsiders (which the RUC always assumed to be imminent), but it bore no relation to any possible positive action on the part of the police. The forward position of the police on Rossville Street changed by perhaps fifty to seventy-five yards, back and forth, for the next forty hours in which cs was used. Any serious police advance was invariably checked by a barrage of petrol bombs, thrown from the rooftops of the nine-storey flats known as Rossville Estates. Groups of thirty Bogsiders manned these rooftops, and they were extremely well equipped, not only with large supplies of petrol bombs and the materials for their manufacture, but also with rudimentary devices for diminishing the effects of a canister which landed on the roof (such as wet blankets and buckets of water). The police were never closer than fifty yards from these flats for any length of time, so that the rooftops were effectively out of range for much of the time. The RUC claim that there was a lull in the use of cs in the early hours of the morning of the thirteenth. But by 11.05 a.m. they were requesting further supplies of the agent by radio. By this time they had moved up to the area of the three-storey maisonettes on the right-hand side of Rossville Street (from the standpoint of the police, facing into Bogside). The police chased youths off these rooftops and then occupied them for some time. It is not clear whether cs was actually fired from this vantage point, although it was definitely fired from the ground in front of the maisonettes. In the sections of the maisonnettes nearest Rossville Street known as Kell’s Walk (and Columbcille Court), hardly a window remained intact, and even weeks later only those visible to a visitor walking down Rossville Street had been replaced. The advance barricade on Rossville Street, near William Street, was ineffective, but the one erected near the high flats was secure throughout, It seemed to take on symbolic importance, as much as practical significance. The Bogside crowd behind it fought indomitably. The sociology of the two contending groups appears to have altered on the second day. The police claim that by mid-Wednesday there was no longer any difficulty with the Paisleyite elements (although such gangs certainly reappeared after working hours). On the Catholic side, the average age of those involved in the fighting is reported to have risen, as the RUC’S tactics increasingly united the population of Bogside behind its young defenders. Many journalists have described how the barricades were manned almost exclusively by young men and boys on the first night, whereas older men played a greater role as the battle wore on and they increasingly saw the situation as a threat to their families and homes. The tendency of the conflict to become a direct confrontation between virtually a whole community on one side and little more than the police on the other was stimulated by the effect of cs on hitherto uninvolved persons, as well as by specific incidents - often based on rumours and misunderstandings.2 During the night of the twelfth to thirteenth a less visible change occurred as well. In the early hours of the morning, under cover of darkness and with all attention focused elsewhere, the army moved its battalion into HMS Sea Eagle to await the time when their intervention would be required. But the army’s readiness had no impact on the events of the next day. Some leaders in Bogside hoped for their eventual intervention, but they had no reason to know that it was in sight. Around midnight of the first night John Hume issued a statement in which he declared that he had lost faith in Stormont’s ability to deal with the situation and wanted Westminster to intervene. At 5.00 on the morning of the thirteenth, he telephoned the Home Office to express this view formally. The Civil Rights Association also put out a press statement during the night, and its terms were rather stronger. It stated: A war of genocide is about to flare across the North. The CRA demands that all Irishmen recognise their common interdependence and calls upon the Government and people of the Twenty-six Counties to act now to prevent a great national disaster. We urgently request that the Government take immediate action to have a United Nations peace-keeping force sent to Derry, and if necessary Ireland should recall her peace-keeping troops from Cyprus for service at home. Pending the arrival of a United Nations force we urge immediate suspension of the Six County Government and the partisan RUC and B-Specials and their temporary replacement by joint peacekeeping patrols of Irish and British forces. We urge immediate consultations between the Irish and British Governments to this end. Time has run out in the North: Bernadette Devlin and Eamonn McCann also issued a statement, which said: The barricades in the Bogside of Deny must not be taken down until the Westminster Government states its clear commitment to the suspension of the constitution of Northern Ireland and calls immediately a constitutional conference representative of Westminster, the Unionist Government, the Government of the Republic of Ireland and all tendencies within the civil rights movement.3 No one behind the Bogside barricades was waiting for Westminster to act. On the thirteenth, the battle became deadly serious. Petrol was procured in vast quantities (amounting to a minimum of a few thousand gallons), by every means from ordinary purchase (collections were taken throughout Bogside by local women) to theft and intimidation. Bathtubs full of petrol were to be seen in Bogside, and petrol bombs were being manufactured with speed and efficiency. Other defensive implements of ingenious design also appeared, from simple wooden planks studded with nails to lacerate tyres of invading vehicles to ‘spiders’, two foot-six inch steel cylinders with steel spikes welded to the sides. Some active steps were taken to diminish the effectiveness of cs, including the use of a fire hydrant to damp down the whole area. In this case, the police responded by making a concerted effort to reach the hydrant, which they then destroyed with a pickaxe, around 4.00 on Wednesday afternoon. Rumours continued to add to confusion and hysteria on both sides. A rumour of a Paisleyite attack on St Eugene’s Cathedral brought more Catholics into the fray, including a large number from Creggan who were described by the chief reporter of the local Catholic newspaper as middle-aged business and professional people. Since such gangs had already tried to burn down the City Hotel, where many journalists were staying, as well as St. Columb’s Hall, it is not difficult to understand the credibility of this rumour. Police radio requests for more supplies of cs were often justified as a response to a rumoured escalation on the Catholic side. At one point, for example, the police on the ground reported that gelignite was about to be introduced, and on late Wednesday they even suggested that ‘gas’ was going to be fired at them from the high flats. Real escalation nearly occurred on several occasions. On Wednesday afternoon, for example, about six men occupied the gas works on Lecky Road, threatening to shut it off (whatever the risks involved) if the police would not cease using tear gas. John Hume spent his whole afternoon persuading these men to leave. Around 3.00 p.m. a Catholic crowd surrounded and attacked the RUC barracks in Rosemount, near Creggan. They aimed to prevent reinforcements from this station from entering Bogside, and the fighting here was serious. The RUC had only four Verey pistols for firing cs canisters, but they quickly borrowed two more from the Army so that cs could be used against the attackers at Rosemount. In the end, a truce was negotiated by Hume around 9.30 p.m., and the siege of Rosemount Barracks was lifted. Further steps were taken to prevent RUC reinforcements from coming to Derry. Both Bernadette Devlin and Sean Keenan telephoned Frank Gogarty, Chairman of the Civil Rights Association, urging the CRA to organise demonstrations in other areas to keep the RUC occupied. Police stations had already been attacked on the night of the 12th in Coalisland, Newry and Strabane. But on the night of the 13th actions took place in Lurgan, Armagh, Dungiven, Enniskillen and Dungannon. In every case, violence erupted to some extent. Belfast was in many ways the most crucial area, and there crowds attacked three more police stations in Catholic areas (Andersonstown, Hastings Street and Springfield Road). With no prospect of bringing further RUC reinforcements from other areas, the police were left with two options: mobilising the Specials or calling in the Army. The prospect of mobilising the Specials was discussed on Wednesday. Shillington met with the city commandant of the Ulster Special Constabulary, but their discussion reflected the political pressures against using the Specials. Shillington wished to avoid giving a pretext for further escalation and he wanted in any case to keep a number of men on reserve for other duties. County Inspector Mahon told the Scarman Tribunal that he considered the intervention of the British troops advisable on Wednesday 13th. District Inspector Michael McAtemney likewise testified that he had told Colonel Todd on the night of the 13th that the Army should come in. In his own words, ‘I said that the time for the Army to be brought in had certainly arrived.’ Manpower was certainly the crucial factor from the police point of view. In normal times, Derry City has a small police force, consisting of ninety constables (of whom only fifty-nine are on the Street) and eleven special constables. A total of 691 RUC men were on hand for August 12, including 559 constables, and this number was theoretically available on the thirteenth as well. But much of this force had been on hand since early Tuesday morning, with only two to three hours off at a time for sleep or meals. (This applied to many members of the Reserve Force who remained on duty until 5.00 p.m. the following day, when they were relieved by the Army.) They had suffered one hundred casualties on the first day and eighty-nine on the second. The Bogsiders gave no sign of weakening. By the afternoon of the 13th, both the tricolour of the Irish Republic and the Starry Plough (the flag of James Connolly’s Irish Citizens’ Army and now a symbol of a workers’ republic) were flying from the top of the high flats. As violence spread to other cities, the prospect of a co-ordinated uprising, perhaps under IRA auspices, caused the RUC command some anxiety. The use of arms in Bogside had to be considered. A few shots were fired, and policemen had drawn their guns on at least one occasion to facilitate the withdrawal of a sergeant who had been hit by a petrol bomb.4 If there was no doubt of the RUC’S superior firepower, there was a recognition, nonetheless, that if the Bogsiders chose to introduce arms they could exact a heavy toll. Moreover, the police had no way of estimating the number of guns and rounds of ammunition in Bogside. Official records showed fifty-four firearms certificates issued to Bogside residents, and ninety-four to residents of Creggan. The bulk of these were shotguns, and the rest were mainly .22 calibre rifles. Another ten guns had been stolen from a sporting goods store in June. But the official record could easily have proved faulty. The police were reluctant to place much faith in it. By Wednesday evening, confrontations continued at many points. A large factory on Little James Street was alight. A barricade was burning at the intersection of Great James Street and Francis Street. Fighting was occurring around the Rosemount barricade. Protestant gangs were in operation, wearing ‘I’m backing Paisley’ rosettes and crash helmets, some carrying makeshift shields bearing a handpainted Red Hand of Ulster. The police had been driven back Rossville Street to William Street, and before the night was out they were to retreat further down William Street to the Chamberlain Street intersection. The pressure from upper William Street continued, renewing RUC fears of a thrust towards the commercial district scarcely a hundred yards away. In government offices more remote from the scene, a number of decisions were taken which also served to inflame feelings. On Wednesday morning, at the RUC headquarters in Belfast, the Security Committee of the Northern Ireland Cabinet met with senior officers of the RUC. Robert Porter announced that he was exercising his powers under the Public Order Act of 1951 to ban outdoor meetings and public processions in Northern Ireland for the rest of the month. Since the first traditional procession to be affected would be the annual August 15 celebration of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, Roman Catholics resented the timing and took the move as further discrimination. That evening, Chichester -Clark made a televised appeal for peace, emphasising the reforms already under way and asserting that their enactment would only be retarded by continuing violence. In the same broadcast, he announced that the Specials would be mobilised in order to assume ordinary police duties. Although he made clear that they would not be used for riot control, the Catholic population hardly trusted this assurance (which in the end was violated in any case). Soon thereafter, Jack Lynch, the Prime Minister of the Irish Republic, also appeared on television. He demanded that the British Government act to halt police attacks on the Bogsiders and stated that the RUC were no longer accepted as an impartial force. He continued, ‘Neither would the employment of British troops be acceptable, nor would they be likely to restore peace conditions - certainly not in the long term.’ He therefore asked the British Government to request immediately a United Nations peace keeping force. The problem, he claimed, was the old issue of partition. In Lynch’s words: Recognising . . . that the reunification of the national territory can provide the only permanent solution for the problem, it is our intention to request the British Government to enter into early negotiations with the Irish Government to review the present constitutional position of the six counties of Northern Ireland. Most concretely, he announced that the Free State Army would set up field hospitals along the border to treat Bogside casualties who were unwilling to seek treatment at local hospitals. Both the British and Northern Ireland Governments reacted negatively to Lynch’s speech. Chichester-Clark denounced it as an ‘intolerable intrusion’ into Northern Ireland’s internal affairs. The first aid workers in Bogside took advantage of the opportunity to send casualties across the border, and limited quantities of medical supplies were obtained from the Irish Army in Letterkenny on Wednesday night. By the morning of the fourteenth, RUC casualties had caused a very serious depletion of available forces in Derry. Of the 691 men theoretically on hand, police records showed only 349 in operation at 7.00 a.m. Thursday. By 10.00 the number back in service had increased to 447, but it dropped to 297 by 11.00 and a low of 255 at 12.30. Manpower then fluctuated for the rest of the afternoon: the numbers recorded are 318, 304, 374, 333, 285 and finally 327 at 5.30 p.m. It is clear from these figures that RUC strength had simply sunk to a position from which no recovery was possible. The timing of the decision to bring in British troops is imprecise. A series of steps were taken throughout August 14. The Inspector General of the Royal Ulster Constabulary formally requested of the GOC Northern Ireland ‘the deployment of troops. . . in aid of the civil power.’ General Freeland acceded to this request with the approval of the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland Governments. Colonel Todd told the Scarman Tribunal that he spoke to Brigade headquarters on the fourteenth and received word ‘to intervene at a time which I considered suitable’. But before the intervention came the mobilisation of the B-Specials. CS was of course still in use, but the RUC had an insufficient number of respirators to equip the special constables. Following the improvisation of the Bogsiders themselves, the Specials wore moist handkerchiefs across their faces when they arrived for duty. Their sergeants routinely carried .45 calibre revolvers and the constables staves. At 4.00 p.m. one sergeant and some twenty constables were deployed along the city walls from the Fountain Street area, visibly uniting them with the Paisleyite crowds from that district. By their own admission, some Specials immediately joined the gangs in throwing stones. The sight of the Specials was alarming to the Bogsiders, but their anxiety was quickly relieved by the arrival of the troops at Waterloo Place around 5.00. Three hundred troops from the Prince of Wales Own Regiment arrived from the Sea Eagle base on the Waterside of the River Foyle. Negotiations were promptly arranged between Colonel Todd and Paddy Doherty (on behalf of the Citizens Defence Association) at Victoria Barracks. By 7.00 the Specials had been removed from duty, the weary RUC had retired from view and Free Derry was granted peace and calm. The army agreed not to enter Bogside. The barricades remained, vigilantes patrolled Bogside’s streets, but the confrontation had ended temporarily.

Notes 1 Quoted in Rev.M.W. Dewar, Why Orangeism, Belfast 1958, 11. 2 The impact of the rumour should not be underestimated. The BBC, for example, broadcast a news flash on the afternoon of the twelth, stating that the Apprentice Boys had marched into Bogside. The effect was immediate; it increased anxiety and added to the numbers in the streets. 3 Both the CRA statement and that of Bernadette Devlin and Eamon McCann are quoted from Martin Wallace, Drums and Guns: Revolution in Ulster, London 1970, 4. 4 And on one occasion without such reason, as could be seen in the ITV film on Bernadette Devlin.

|

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||