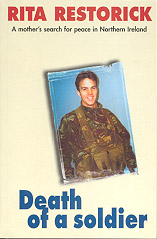

'Death of a Soldier: A mother's search for peace in Northern Ireland' by Rita Restorick[Key_Events] Key_Issues] [Conflict_Background] The following chapter has been contributed by the author,Rita Restorick, with the permission of the publishers, The Blackstaff Press. The views expressed in this chapter do not necessarily reflect the views of the members of the CAIN Project. The CAIN Project would welcome other material which meets our guidelines for contributions.  This chapter is taken from the book:

This chapter is taken from the book:

Death of a Soldier:

ISBN 0 85640 670 8 (Paperback) 239pp

Orders to local bookshops or:

This publication is copyright Rita Restorick (2000) and is included on

the CAIN site by permission of Blackstaff Press and the author. You may not edit, adapt,

or redistribute changed versions of this for other than your personal use

without express written permission. Redistribution for commercial purposes

is not permitted.

From the back cover: Englishwoman Rita Restorick is the mother of the last soldier to be killed in Northern Ireland. Since his death, she has channelled her grief into tireless campaigning for peace. Twenty-three-year-old Stephen Restorick was killed by a sniper’s bullet on 12 February 1997 as he manned a checkpoint in south Armagh. This book, published to mark the third anniversary of his death, is the moving testimony of his remarkable mother, Rita. Written in a direct, spare style with no hint of self-pity, Death of a soldier nevertheless conveys with almost unbearable poignancy the intense grief which became for Rita Restorick a powerful impetus to work for peace in Northern Ireland. Like many English people, her knowledge of the situation was sketchy and the period since her son’s death has been for her ‘a sharp learning curve of the history of Ireland and the background to the conflict’. Her compassion and feeling for the people of the north as they inch their way towards peace, and her personal understanding of how immensely difficult the oft-demanded ‘compromises’ can be - the prospect of an early release under the Good Friday Agreement for the man convicted of her son’s murder is torturing her - make this extraordinary book as compelling as it is courageous. Front cover photograph:

RITA RESTORICK was born in Market Drayton, Shropshire, in 1948. She married John in 1967 and had two sons, Mark (born 1970) and Stephen- the subject of this book (born 1973 and died February 1997). Rita lived in Libya with her husband when he served in the RAF during the time that Colonel Gaddafi seized power. She worked for Peterborough City Council as a secretary until Stephen’s death. She received the Champion of Courage Award with Lisa Potts and Doreen Lawrence at the Women of the Year Lunch 1997.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to the Blackstaff Press for restoring my faith in publishers after rejection of my manuscript by the large ones, also to Michael Bilton for his advice and encouragement and for insisting that I had to write the book myself for it to have impact. Special thanks go to my husband John for allowing me the time and space to do what I needed after Stephen’s death and for understanding why writing this book was so important to me. My thanks also to the Compassionate Friends, a nationwide support group for bereaved families, through which John, Mark and I were helped on this hard road of grieving by the kindness and example of other bereaved parents. Finally, a special thank you to all the people in Northern Ireland and the Republic who through their cards and letters showed us that Stephen’s death had touched them deeply and that they wanted an end to the conflict.

IT WAS MONDAY, 24 FEBRUARY 1997, Stephen’s twenty-fourth birthday, and all our family and his friends were with us. But we weren’t celebrating his birthday. We were at Peterborough crematorium attending his funeral. There on the dais was his coffin draped with the Union Jack. Stephen was the last British soldier killed in Northern Ireland before the peace settlement, a victim of the IRA’S attempts to bring about a united Ireland by force of arms. He was shot by an IRA sniper at a vehicle checkpoint in Bessbrook, County Armagh, close to the border with the Republic of Ireland. In an instant that bullet had shattered our lives. Nothing would ever be the same again for us and our wider family. This book is about Stephen’s life and death and my attempt to survive the nightmare that every mother dreads. It follows my efforts to channel my grief in a positive way, to make Stephen’s death and my grief a focal point of what so many mothers had suffered in Northern Ireland and Great Britain as a result of IRA and loyalist violence. Instead of allowing myself to be overtaken by bitterness at people who, as I saw it at the time, had to a greater or lesser extent caused my son’s death, I wanted to reach out to them, to say that I was just the latest of many mothers who had suffered the loss of a son. When Stephen was killed we hoped his death would be the last, but it was a futile hope and many more killings followed. Stephen was, however, the only soldier killed in Northern Ireland in 1997. I was driven to do what I could to move the ‘peace process’ forward. On 9 February 1996, just one year before Stephen’s death, the IRA cease-fire that had come into effect on 1 September 1994 had ended with the bombing of the Canary Wharf office complex in London’s docklands. A huge opportunity had been allowed to slip away during that cease-fire. The people of Northern Ireland had known peace during those few months, and did not want to go back to how things had been for the past thirty years. Sensing this feeling I wanted to be a symbol of the hopes of all mothers who wanted an end to the violence. I also wanted English people to take an interest in the suffering that had been allowed to happen in Northern Ireland, instead of only taking notice when the violence crossed over to England. I don’t know how far I succeeded in those aims. In the two years after Stephen’s death events in Northern Ireland were momentous. Throughout those two years, I felt that Stephen was with me every step of the way, pushing me on when the situation seemed so bleak, telling me to speak out to stop other young lives like his being thrown away. It has been for me a crash course in the history of Ireland and the background to the conflict. I believed that if I was to put forward my views on what I thought about the situation in Northern Ireland, I had to do so with some basic knowledge of the events that had led to the present situation. Like many English people, I didn’t even know the names of the six counties of Northern Ireland before Stephen’s death caused me to take a deeper interest. The last time I saw Stephen alive was on Boxing Day 1996, Saint Stephen’s Day. This led me to use as a guiding light the words spoken by Saint Stephen when he was killed: ‘Don’t blame them.’

THE TWO DAYS SINCE Stephen’s death had been emotionally draining for us. Realising this, my elder brother Raymond insisted we went to stay the weekend at his home in Shropshire to escape the media pressure. Mark, however, preferred to stay in Peter- borough with his girlfriend. Our journey to Shropshire was terrible; I don’t know how John managed to drive with the pain we were experiencing. It took far longer than the usual two hours as we had to stop now and then to get out of the car and release our emotions. We held each other tight as we looked out across the rolling countryside. How could everything still be so beautiful, how could the birds still sing and the sun still shine? Stephen, our smiling, fun-loving son, was dead and yet everyone still rushed around. Life goes on but how could it? After lunch at my brother’s house, John and I went for a walk along a nearby country lane. It was a beautiful, spring-like afternoon and we needed to be on our own for a while with our thoughts. Mine turned to Lorraine. I decided to send her some flowers to show our appreciation for her words of compassion. We found a florist’s shop and I told the assistant we wanted to send some flowers to a lady in Bessbrook, south Armagh. Checking her list of florists in that area, she said the nearest one was in Warrenpoint - a chill went down my spine as I remembered the eighteen soldiers killed there by the IRA on 27 August 1979. We told her the flowers were for Mrs Lorraine McElroy and were from John and Rita with the message ‘Stephen is now back in Peterborough, thank you for being there for him when we couldn’t.’ The assistant made no connection with the murder of a soldier in Northern Ireland, despite Lorraine and Stephen having been mentioned in every newspaper and news bulletin for the past two days. This was our first experience of something that had shattered our lives not even making an impact on other people. The same thing happened to us in Peter-borough, so it was not just because we were in a small Shropshire town. That night, tired from the travelling and emotionally spent, we soon fell asleep. But I woke up at 3 a.m. and tried desperately to think what I could do to prevent Stephen’s murder leading to retaliation and spiralling sectarian violence. I decided to write to President Clinton in the USA as there had been such high hopes when he visited Northern Ireland in 1995. On 30 November he had told a cheering Belfast crowd: ‘You must say to those who still would use violence for political objectives: you are in the past; your day is over.’ Still shaking from the emotions surging through me, I could barely hold the pen but I managed to do a rough draft which I wrote out again later that morning. Outlining what had happened to Stephen, I told the President I was writing in desperation and hoped that he could help. I begged him to do all he could to bring all sides together round the table to start talking, and to keep them there. The peace process had ground to a halt, and hardliners were trying to incite the violence again. I said, ‘I am writing this at 4 a.m. as I cannot sleep for if I sleep when I wake up the nightmare of Stephen’s death will be true but I so want to sleep because the pain of knowing I will never see him again is too much. I will never again be able to feel him hug me, see his smiling face or hear his voice.’ I told him of the messages of sympathy people had sent from Northern Ireland saying that they did not want the violence to start again, they had known peace for a while and did not want to go back to the horrors of previous years. I ended by saying, ‘Please, please, please do all you can to make sure no other mother has to go through the hell I am going through at the moment. As a father yourself I am sure you can imagine how land my family are feeling at the moment.’ Emotions flowed over John and myself in waves. Despite being with my brother and his family, sometimes we just had to be alone together, holding one another close and crying. Later that morning I told my brother that I felt I was going mad, that I was imagining everything that had happened, it did not seem real, could not be real. He reassured me, saying even he had difficulty believing it at times. To reinforce the fact, I would read over and over again the newspaper articles about Stephen’s murder. But even then it seemed to be only his name on the page, it hadn’t really happened to him. Later I explained this feeling by saying how long can a dream last? Could you dream seeing your son lying in his coffin? Could you dream going to his funeral and meeting all the people there? Then could you wake up and say, ‘I had a terrible dream’? My younger brother Neil, his wife Janet and their sons Andrew, David and Christopher arrived later that morning and tears were shed between us. The boys were all stunned by what had happened, death being a rare visitor to young men. They had many a struggle trying to come to terms with Stephen’s death. As we sat talking, memories of Stephen’s antics with his cousins came to mind, such as the time Stephen presented his uncle Ray with an ashtray from a pub and said that he would have brought a bar stool as well but his brother wouldn’t help him carry it. Such were the harmless, laddish things he got up to. We were soon even laughing a little - such were the memories of Stephen’s personality. When we returned home on the Monday morning, I started to put the service together. John’s father and my nephews Paul and Christopher wrote anecdotes about Stephen, as did his friends Colin, Lisa and Asa. There was the music to choose as we were not, of course, having hymns. We had wanted an upbeat number to finish the service, the type of tune Stephen would have been dancing to at a nightclub. We chose ‘Born Slippy’, a typical techno-rave number with a driving beat. Unfortunately we had too much music, even though the other tunes were edited halfway through. So ‘Born Slippy’ was dropped, to the disappointment of Stephen’s cousins and friends, but probably to the relief of the older people at the service. Whenever I hear that tune it epitomises the energy and pure zest for life that Stephen had. I can see him dancing away with a smile on his face as he chats up a possible new girlfriend. More cards arrived on Monday, many only addressed to ‘The Parents of L/Bdr Stephen Restorick, Peterborough’. But two letters didn’t arrive - those I had expected from the prime minister, John Major, and our local Conservative MP, Dr Brian Mawhinney, who is himself an Ulsterman. Perhaps I was naïve to expect them to write so soon. But it made me very sad and angry that there were no letters from the very people whose policies Stephen had been carrying out, yet people who did not know us had written. In frustration I phoned our MP’s office, asking if he had been out of the country in the past few days. His secretary said he hadn’t, so I told her how hurt I was that I had not heard from him. I also asked her to contact the prime minister’s office with the same message. We received their letters in Wednesday’s post, a full week after Stephen’s death. Without my knowing, my seventeen-year-old nephew Christopher also phoned the prime minister’s office on Monday. Having heard me express my feelings about not receiving a letter from the prime minister, he rang 10 Downing Street to say how upset his Auntie Rita was. That evening we went to the chapel of rest to see Stephen. Some people would say that you should remember someone as they were and not see them after their death. I had followed this advice when both my parents died, despite my need to see them as I had not been there when they died. John’s parents are both still alive, so Stephen’s death was the first time he had faced this dilemma. Apprehensively, we went in to see Stephen. I saw a very plush coffin with a white satin lining; Mr Claypole said the army had done us proud, it was a very expensive coffin. I said, rather abruptly, that it was the least they could do as he had died for his country. Stephen was dressed in his number one black dress uniform, as I had requested. He looked as if he was asleep and I was surprised at how long and beautiful his dark eyelashes were. But something seemed different about his hair. Then I realised: there was no wet-look gel on it. I told Stephen how much I loved him. Silently I told him I was sorry, sorry that people in power had allowed this to happen, had allowed young men to lose their lives when a lot of people in England couldn’t care less about what happens in Northern Ireland, and many of those in Northern Ireland would not compromise in order to find peace. After a while we left Mark alone with his brother for a few private moments. During that week we received hundreds of cards and letters. There were messages of sympathy from the principal Church leaders in Northern Ireland. The Archbishop of Armagh, the Most Reverend Dr Robin Eames, wrote, ‘I have just returned from visiting your son’s colleagues at Bessbrook. All I spoke to in Bessbrook referred to your son with pride and respect. His young colleagues are devastated. All I can add to those words you have already received is this: you must be proud of your son. You will remember him with pride. He died serving this community at a time when ordinary decent people here need protection. He was doing his duty with great professionalism. Your sorrow and anguish is shared by us all.’ The Most Reverend Sean Brady, the Catholic Archbishop of Armagh, wrote, ‘Your lack of bitterness and noble sentiments have edified very many people. Among many others, the parish priest of Bessbrook has acclaimed your tremendous generosity of spirit and nobility of heart in a recent interview. I hope that Stephen’s death may not have been in vain, but may hasten the day of lasting peace and reconciliation in this troubled land.’ He issued a press release on the day after Stephen’s death in which he said, ‘I am totally appalled by the shooting of Stephen Restorick, the young soldier murdered in Bessbrook last night. Mrs Lorraine McElroy, the young wife and mother who was injured in the incident, has spoken poignantly this morning of the horror she experienced at witnessing a life taken so cruelly. I offer my profound sympathy and prayers to the soldier’s grieving family. This shooting is an evil deed. Its only purpose can have been to undermine the already-fragile peace. Unquestionably, it increases a sense of fear and horror. The desire for peace is very deeply felt throughout the whole community. I appeal to all right-thinking people to reject out of hand whatever could in any way favour or support this return to violence. Violence is the enemy of peace.’ The Moderator of the Presbyterian Church, the Right Reverend Dr D.H. Allen, wrote to express the sympathy of the whole Presbyterian Church: ‘It deeply grieves us that lives are lost in this pointless war which the IRA has waged in our land for many years. It is even more so when young men like your fine son Stephen, who give themselves to serve and protect us, are so viciously and callously murdered.. . We are m debt to your son and will always be. He gave his life for our country and we thank him. We thank you for all you gave to him to make him such a wonderful person who was so well liked by all who knew him. We know that you will miss him very much and we want you to know that we shall not forget him.’ Another message came from a Methodist church in Belfast: ‘Our hearts have been hurt and saddened by the death of your son Stephen. I would ask you to forgive us for the loss of your boy. Please forgive us. We all must bear some of the guilt. Thank you for your impassioned plea to those who would plan to do further evil deeds. I pray that God will use your words to touch the hearts of those who plan and carry out these evil deeds.’ A Catholic priest in Belfast wrote, ‘It is with deep sadness that I write this letter on the occasion of your young son’s death. By all accounts Stephen was a fine young man who has become one more of the victims of a senseless "war". I have had the sad duty of being with many young men who were slaughtered like Stephen, I have buried them and have seen their poor parents like you left to grieve their memory. Thank you for your appeal that more violence will not come from Stephen’s murder; those words are a light amidst the darkness. I pray that the person who shot your son will be caught and brought to justice. There are many mothers and fathers here in Northern Ireland who have gone through what you are experiencing and are holding you very much in their prayers.’ A sister from a convent in the Republic wrote, ‘All the members of our community were deeply shocked at this awful deed and we abhor the actions of the IRA and what they stand for. I do so admire your nobility and dignity all through this terrible tragedy. You have shown you are able to forgive and also to plead for peace in Northern Ireland. Hopefully your shining example will be instrumental in furthering the cause of peace there.’ Every death causes a ripple of emotion amongst family, friends, work colleagues. With Stephen’s death that ripple spread to people who never knew him personally but were moved by his smiling picture in their morning newspaper and Lorraine McElroy’s moving words. These people sent cards and letters from towns in Britain, Northern Ireland, the Republic, and other parts of the world. A letter came from the widow of Lieutenant-Colonel David Blair of the Queen’s Own High-landers, who was killed with seventeen other soldiers on 27 August 1979 at Warrenpoint. She wrote, ‘I just wanted to say how much I admired the wonderful way in which you bravely expressed all that my family and I felt in similar circumstances years ago and still feel today. My husband used to say that it’s the ones who are left behind who suffer, and your wonderful son suffers no more. You must be very proud of him, he has become part of history and his death, I am sure, has not been in vain because people have been so outraged by his murder. I had been so encouraged by the peace that has lasted for a while in Northern Ireland. Let us hope and pray that the peace will return, perhaps as a consequence of your son’s death.’ Some of the messages from Northern Ireland and the Republic showed what people thought about Stephen’s death and the political situation there. A Bessbrook grandmother wrote, ‘We are all very, very disappointed that another young life has been taken away, by some person who is not worthy to be called a human being. How can they do this kind of thing? I am a Catholic and I am disgusted that this evil is in our society and we do not know who this person is. We do not want this happening in our country as then we are all thought of as being the same as these murderers. My daughters grew up in the troubles and it is still going on for their children. I felt I must write to you and let you know there are a lot of good people over here in Ireland.’ A lady from Newry wrote, ‘I could only imagine that in your position I would be full of hatred and bitter beyond belief. I just hope you realise that at least 90 per cent of the ordinary, decent people have nothing but the utmost sympathy for you and all the other innocent people who have suffered at the hands of these mindless monsters. I assure you although we share the same religion they by no means speak for the ordinary people.’ Many more wrote saying that the majority of Catholics did not support the IRA. A man from Bangor, County Down, said, ‘His life was taken so suddenly by a cowardly act in the name of Irish freedom. Many people believe this is supported by Irish Catholics. I, being an Irish Catholic, totally condemn this despicable act. Stephen came to Northern Ireland to protect the people of both communities and he did this to the best of his ability and his life was taken while doing his duty. I hope no more lives have to be lost before these sick people realise that no one in Ireland, North and South, wants any part of it. I thank you for the protection your son provided to the people of Northern Ireland.’ A grandmother from Derry wrote, ‘I am so sorry your beautiful son had to come to this country to lose his young life in the awful cruel way he did through the awful hatred and bitterness that the people of this beautiful country have for each other. I myself am a Catholic but that never made any difference to me or my sons and daughters, as we did our best to bring them up in that way and some of my very best friends are not Catholics. Words fail me to explain the disgust I feel for people who do such awful things. Deep down they really are cowards in my mind. Please don’t judge us all as being such awful people.’ In similar vein, a Protestant lady from Belfast who signed herself ‘A very sad and sorry old lady’ wrote, ‘This terrible deed is condemned by 95 per cent of the citizens of Northern Ireland. We who have lived here all our lives cannot understand the terrible evil. I am a Protestant but many of my friends are Catholic and we all condemn these killings and bombings. As I look at the lovely colour picture of your "little boy soldier" in today’s paper, I feel sick at the thought of the hatred and bitterness that leads men on to evil deeds. I have three grandsons of around Stephen’s age so you will know that I understand.’ A man from near Belfast thought there was a higher purpose behind Stephen’s death. He wrote, ‘You must feel very proud of Stephen. Please try to draw comfort from the certain knowledge that from this awful tragedy will come good - his death will not be in vain. God moves in mysterious ways which are sometimes hard for us to grasp and understand. Your dignity and restraint in these circumstances was noted and talked about by many of my friends. You have set a worthy example for us to follow.’ Similarly, some saw Stephen’s death as a turning point; a lady from near Dundalk wrote, ‘Personally I think that Stephen’s death may not have been in vain. It could I think be the key to the peace we are all seeking. I really believe that out of his death could rise the peace.’ I hoped so much this might be so but also wondered how often people in Northern Ireland and in the Republic had seen such hopes destroyed by yet another murder. ‘An ordinary housewife in Northern Ireland’ said she had grown up in the troubles and had always been thankful for the peace-keeping forces, adding, ‘I am often struck by how young the soldiers look and when we sometimes exchange a "Good Morning" I tend to think of their folk over in the mainland and their concern for the safety of sons serving in Northern Ireland. For every parent in that position, it must be their worst nightmare that some day they’ll receive news such as you got last week. All I can say is that the ordinary people of this Province are in a situation over which they have no control and although there is relative peace at the moment, no one doubts that violence could erupt again very soon. There is no simple answer to the Ulster problem - the vast majority of people really want peace and are grateful for all that the security forces have done to keep ordinary people safe.’ Many who wrote did not sign their names but they indicated, or we presumed, that they were Catholics. One, who just signed her letter ‘A Mother’, wrote very movingly: ‘I have sons of my own and I can’t even begin to know how you must feel but I shed tears for Stephen and then again I cried with gratitude when you appeared on TV and said you wanted peace in Northern Ireland. We are just ordinary people who want to live our lives in peace but we are being destroyed by terrorists like the evil, cowardly man who took your son’s life. Over the years I have cried many times about the young English soldiers whose lives have been taken away and during these past months I thought maybe they had stopped shooting soldiers in cold blood. Stephen was a lovely lad, it is such a tragic loss.’ There were many letters from the Irish Republic. A couple from Santry expressed their sympathy and added: ‘Many others from this side of the Irish Sea share our sentiments when I say we were shocked, horrified and disgusted to hear the news on TV of another brutal, cowardly murder in Northern Ireland. Poor lovely Stephen killed because he happened to be a soldier doing his duty trying to protect others but caught up in political turmoil which has caused so many heartaches in so many homes both in Britain and throughout Ireland. We both originated from Northern Ireland and shared different religious beliefs. We have lived in the Irish Republic for the past twenty-four years. Each time we hear or have heard of another atrocity we are so saddened at the futility of all this loss of innocent lives. We were particularly touched by the pictures of such a handsome young man as Stephen whose life has been so prematurely taken away from him.’ A few were a little more forthright in their condemnation of Stephen’s murder. The sender of one card from Northern Ireland wrote, ‘He died at the hands of scum who hide and creep around. Please do not think all people in Ulster are such lowlifes, we try to live as normal lives as possible. I know that people on both sides of the divide are shocked and sickened at this cowardly act. Please be strong, your son was a hero and died trying to protect the good respectable people of Ulster. And for that we are forever in both his and your debt.’ Some spoke out against the politicians. An Irish Catholic mother who wrote after it became known that I had sent a letter to all the politicians involved in Northern Ireland said, ‘I want to congratulate you on your very courageous gesture in sending letters to John Major and Gerry Adams as they are the main ones who need to talk and get the peace for all of us established on this island so all of the young English men who are sent here in the army can go home and be safe. The cease-fire was here two years ago and John Major, Paisley and Trimble et cetera did nothing about it. I hope you can find some comfort from the fact that you are trying to help us all over here and that your dear son did not die in vain.’ A man from County Westmeath in the Republic wrote in similar vein: ‘This killing (and the manner of it) has further alienated many, many Irish people from giving any support whatsoever to the "republican" solution to the Irish "question". Too many people in high places are so entrenched in their own personal and party positions and ideologies that it is no wonder no progress is being made. All the "participants" seem to do is blame the "others" to justify their own lack of action. They are therefore happy justifying their centuries-old prejudices and see no reason whatsoever in making even one step forward in progress for fear also of "losing their traditions".’ A man from Limerick wrote, ‘When I reflect on the senseless protracted violence that has prevailed in Northern Ireland down the years, I ask the rhetorical question why or how can the political leaders within Ireland and the United Kingdom continue to allow the present situation to drift endlessly on. Despite the convening of the all-party talks unless there ss a Christian willingness by all sides to conduct these on an unconditional all-inclusive basis, underpinned by a spirit of mutual forgiveness for all previous unjust maiming and taking of human life, and a determination to negotiate a new and lasting peace in Northern Ireland there can be no realistic prospect of having the problem finally resolved. It is a stark fact that throughout the past twenty-five years this conflict has resulted in the death of at least 3,000 human beings, including your own son. I am heartened that there are people like yourselves, the parents of the late Tim Parry, the late Senator Gordon Wilson, who can visibly display such practical Christianity at a time of such personal pain and suffering caused directly and arising directly from the conflict in Northern Ireland. Hopefully your forgiveness and prayers along with those of the peace-loving vast majority of the people within the islands of Ireland and Great Britain will help to expedite a final peaceful resolution to this conflict.’ Young people also wrote. One, now a Methodist Youth Pastor in Lurgan, said: ‘I am a 23-year-old young person living here in Northern Ireland. Your son was a fine young man, almost the same age as myself which makes it hard for me to comprehend. This is my land your son was bravely defending, and that bravery contrasts with the cowardice of the person who shot him. Your words of hope echoed across Northern Ireland and serve as a reminder to us all who live here of our obligation to play our part to bring about a new future, a new day of hope. That requires all the people of Northern Ireland. As a young person I will play my part.’ A nineteen-year-old man from the Republic wrote, ‘What appalls me are these men of violence who spread this misery to innocent people like you and your son. I can only say that you have the support of millions of Irish people not just here but throughout the world. We all completely reject this mindlessness. We all wish we could live in peace with our Northern Irish neighbours and we all wish that the tragic history of these islands could be forever consigned to history. I know you, like many English people, wonder why your sons have to be on this island in the first place, why they have to risk their lives. I can only say that without them Northern Ireland would be in a worse state than it already is. I can only pray that your son’s death was not in vain, that it will drive the effort towards peace and one day bring reconciliation to this divided island.’ A lady from Belfast gave us advice on how we should react in our grief, which I have tried to follow: ‘May I just say never let bitterness or hatred ruin your lives; your anger may be overwhelming and justifiably so, but dwelling on thoughts of the perpetrators will only cause you to become more embittered, and your son would not wish that.’ One particular Mass card was very special for me as it was just signed ‘A Crossmaglen Family’. I knew that Crossmaglen was one of the staunchest republican areas in County Armagh and a place where many soldiers had been killed. To receive such a card truly said to me that not all Catholics in that area were celebrating Stephen’s death. We had been warned by the army that we might receive some threatening or triumphant letters from republican sympathisers, but this did not happen. Those with such views perhaps felt they had achieved something with Stephen’s death and there was no need to further hurt his parents. Some people sent us very moving poems they had written. One of these poems, ‘My Son’ by Elsa Summers of Burnley, speaks for all mothers who have travelled through the ‘valley of tears’ after the death of a son they loved more than words could ever say. She wrote it following the death of her 24-year-old only son Stuart in May 1996. The tears they flow Like pebbles on a beach That week is something of a haze. I remember going into the centre of Peterborough and seeing all the people rushing about their daily lives: I just wanted to stand there and scream, to tell them to stop and listen to what had happened to my son. Did they not know or care? I could not cope with all the people rushing around. I was in a daze. It was painful to have people near me, as if I had lost a layer of skin. Peterborough is so big that many people do not know us. John’s mother had the opposite problem. Living in the small town where she was an infants teacher, she is well known. She was upset by all the people who stopped her to say how sorry they were about her grandson’s death. We visited the crematorium. Never having been there before, we wanted to see the layout before the day of the service. In the chapel, one long wall is a huge window, and I hoped the army would check the grounds in case a sniper decided to fire on the soldiers in the chapel. We decided we wanted the coffin to remain on the dais when we came out of the chapel. Also we wanted the cross to be left on the wall for those with religious beliefs and to symbolise our hope that if there is a God he would understand why we had chosen a non-religious service. Should we have an urn or a casket for Stephen’s ashes? We expected to move to Nottingham in the future and we didn’t want Stephen to be left in Peterborough. So we chose a casket: then we could either scatter his ashes or inter them later. Some news reports of Stephen’s death said that he had hoped to get engaged soon. A woman rang to say that Stephen and her daughter Lindsay had talked about getting engaged although they had only known each other since Christmas. She said Lindsay wanted to see Stephen at the chapel of rest, would it be possible? For us this was a very difficult decision, Stephen hadn’t said anything to us about her, and although her family lived locally we had never met. We felt very protective towards Stephen, and the undertaker had advised us to accompany anyone wishing to see Stephen. Wanting to meet Lindsay first, I asked her mother to bring her to our house the following evening. When I met Lindsay, I could understand why Stephen had been attracted to her. She was very pretty, blonde, and petite. As she too was in the army, Stephen probably thought she would have more understanding of life in the services, how people have to leave at a moment’s notice and be away from home for long periods. She showed me Stephen’s letters which showed his feelings for her. She came with us to the chapel of rest the next evening. We led her into the room where Stephen lay and stood with her for a few moments. I told her that if she wanted to kiss him it would be better to do so on his hair (I didn’t want her to feel how cold his skin was). Then we left her on her own with him. Lindsay came to the funeral but we did not hear from her again. A year later in the local paper I saw a photo of her wedding to another young, smiling soldier. It was very painful for me, thinking what might have been. The parents of another girl wrote saying how much Stephen had meant to them and how he had continued to visit them and her grandparents even after the relationship had ended. They asked if they could visit Stephen at the chapel of rest. We met them there and were very moved by the feelings these people, who we had never met, showed for Stephen. He had certainly touched many hearts. Wednesday was one of the two days when the funeral could have been held. It was the most awful day, with gale-force winds and rain lashing down, so I was glad we hadn’t chosen that day. It was also the day I wrote to the prime minister, the Northern Ireland Secretary and all the Northern Ireland MPs, and the leaders of the Labour Party and the Liberal Democratic Party asking them to do all they could to find a peaceful solution in Northern Ireland and make progress towards talks. I also wrote to Gerry Adams, president of Sinn Féin, asking him to pressurise the IRA to call a ceasefire from Easter. I was struck by the fact that Stephen had died on Ash Wednesday, the first day of Lent, and in the letter I emphasised that people give things up for Lent. Stephen had given up his life, couldn’t the IRA give up their refusal to call a ceasefire? At that time I knew very little of Irish history and especially the Easter Rising of 1916. Now I realise that Easter wouldn’t be an appropriate time for republicans to call a ceasefire. With the letters I sent a photograph of Stephen in his army uniform and asked them to keep it on their desk until Easter. I realised a couple of days later that perhaps a photo of Stephen in army uniform wasn’t suitable for Gerry Adams so I sent one of Stephen with his friends in a nightclub so that Adams could see him as a young man full of life. Would my letters have any effect? Why should Stephen’s murder make any difference when so many others had been killed? But I had to try. These letters led to a terrible family row. Our emotions had been building up like steam in a pressure cooker since Stephen’s death. I was rushing to get the letters in the post that evening as the local paper wanted to print the text the next day. Addressing the envelopes, I asked Mark to help by putting the letter and photo of Stephen inside. He did this for a few moments and then left the room. I, in my haste, thinking he just didn’t want to help, became angry. John came in, and as I told him what had happened, I lost my temper and threw a cup across the kitchen, smashing it. All the pent-up emotions flooded out. Mark told his dad it was too upsetting to see his brother’s face each time he put the photo in the envelope. Mark, being the sort of person he is, hadn’t felt able to explain this to me. I, being the type of person I am, was dealing with my loss by sending these letters. I hadn’t realised it would affect Mark differently. I doubt if the politicians thought for one moment about the sheer emotional cost of those letters. Later that evening we went to Sue and Mike’s for a meal but we just picked at the food. I was in tears because of the argument over the letters, so Mike took John and Mark to the sitting room to talk while I poured my heart out to Sue. She and Mike were very supportive at this very difficult time for us all. Referring to these letters, the Ulster Quaker Peace Committee in Londonderry wrote after Stephen’s funeral, ‘We very much appreciate that in the midst of your bereavement you found time and courage to write to our political leaders to encourage them to keep open channels of communication between all parties. You have added significantly to the work being done to try to heal the divisions within our community. We would endorse your vision that Stephen’s death may "be a catalyst for peace".' That week, Colin and Lisa, Stephen’s friends since schooldays, came to see us. It was good to have young people in the house. They were very upset about Stephen’s death but soon turned our sadness to laughter as they told us of their memories of him. I said that the neighbours would be knocking on the door complaining at the laughter when we should be tearful. Colin, jokingly, said there would be lots of girls at the crematorium, some of them with prams. Getting his meaning, I told him I hoped there would be a pram there with Stephen’s baby in it. At least then there would be a little bit of him left for me to love. But on the day there were no prams and no babies. What should I wear to the funeral? One night I woke up knowing the answer, my apricot-coloured jacket with a flowered skirt. I woke John up and told him. After he had fallen asleep again, I suddenly thought that some people in Northern Ireland would see apricot as orange and my attempts to be neutral would be defeated. So I woke him again and explained to him why I could not wear my apricot jacket after all. I thought to myself, I’ve lost my son, I shouldn’t have to worry about what clothes I wear at his funeral. I wanted people to have a memento of the funeral. As it was not a religious service there would be no printed hymn sheets with Stephen’s name on. We decided to have a card with Stephen’s name and the date of the service on the front. On the reverse John wanted the poem ‘Do Not Stand at My Grave and Weep’. It seemed to express how Stephen would want his family and friends to see his death in the future. John didn’t know all the words, but out of the blue two copies of the poem arrived in that morning’s post. One came from a nun in southern England who said it was found after the death of Lance-Bombardier Stephen Cummins near Londonderry in 1989 in an envelope addressed to his parents. The other copy came from Stephen Cummins’s parents saying they knew what we were going through; their son had been twenty-four when he was killed in Northern Ireland. The poem seems to touch a lot of people - it was sent to us many times over the next few days: Do not stand at my grave and weep. When you awaken in the morning’s hush I had a constant pain which felt as if my heart had been torn in two and that I was crying tears inside that could not or would not come out. When people talk of a broken heart the phrase is now all too real for me. I knew Stephen would not have wanted us to be in floods of tears but to remember the happy memories, but it was so hard at times. I thought of all the other parents of soldiers who had travelled this road before us. Was it worse to lose a soldier son when so many others like him were being killed, as in Northern Ireland in the past? More people would be in the same situation as yourself so you could share your grief, but any significance to his death would seem to disappear. Or was it worse to be like us, where there was no one in exactly our position and few parents locally had lost a son or daughter? Two of our Irish friends visited us that week, keeping up the Irish tradition of visiting the bereaved to say ‘sorry for your troubles’. Columb, a former work colleague, is an architect and comes originally from Belfast. Eamonn, from Londonderry, lived near us. His son Bernard and Stephen were friends together in the Air Cadets but had lost touch since. Eamoun said he presumed we knew about his brother’s past. Realising we didn’t, he told us that in the early seventies his youngest brother became involved in the IRA at fifteen years old, had been arrested for sending letter bombs to prominent people in Britain (none of whom, fortunately, were killed or seriously injured) and was sentenced to a long prison term. Since his release he had turned his back on the IRA. His father, a teacher at a Catholic school in Londonderry, and his mother had been totally unaware of their son’s involvement until his arrest. It really showed us how the tentacles of the IRA permeate the Catholic community. John and I visited the chapel of rest again on Sunday, the day before the funeral. Mark had made his last visit on his own two days earlier. I took with me a small spray of silk flowers sent to me by a mother who had kept them from her soldier son’s wreath, and a single red carnation from the wreath sent by STOP 96, a peace group in the Republic of Ireland. These were placed in the coffin with Stephen as symbols of our hopes for peace in Northern Ireland. I gently touched Stephen’s dark-brown hair and said goodbye to him. I told him that we would never forget him. Again I told him that I was so sorry that my generation and my parents’ generation had not been able to find a solution to the problem in Northern Ireland and that the situation had been allowed to drift on so long at the cost of so many young lives like his. I looked for the last time at my handsome young son, not wanting to leave that room but knowing I had to and that I had to be strong for him tomorrow.

|

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||