'Towards Partition', from, The Making of a Minority,

|

| FOREWORD BY JOHN HUME |

| INTRODUCTION |

| CHAPTER ONE

THE ORIGINS OF TWO TRADITIONS |

| CHAPTER TWO DERRY'S PART IN IRELAND'S "PHONY" WAR 1912-14 |

| CHAPTER THREE 1916-17 CHALLENGE TO CONSTITUTIONALISM |

| CHAPTER FOUR TOWARDS PARTITION |

| CONCLUSION |

| NOTES |

| ABBREVIATIONS |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY

.....PRIMARY SOURCES .....NEWSPAPERS .....OFFICIAL PUBLICATIONS .....SECONDARY SOURCES .....THESIS .....INTERVIEWS .....TELEVISION DOCUMENTARY |

| INDEX |

I wish to record my appreciation for the assistance and patience of Dr Gerry O'Brien (Magee College). I am also grateful for the advice and courtesy of the staff at Magee College Library, Central Library in Derry and Public Records Office, Belfast. I received practical advice and encouragement from Maureen my wife and from Maura my daughter. Patrick and Paul also gave practical help and amused encouragement when necessary.

I would also like to record my thanks to the following: Dr Eamon

Phoenix for helpful insights, P J Doherty, Anton McCabe, Mr Leo

Emerson, Moya Jane O'Doherty, Dr Mary Leary and Ken Ward. Also

to Magee College, the Bigger-McDonald Collection and the William

Clifford Collection for the use of their photographs.

The period 1912-25 must rank among the most dramatic and traumatic phases of Irish history. On some levels its history is fascinating, on so many others it is frustrating. This comes through very clearly in this study by Colin Fox which explores the experience of Derry City in the context of the political agitations and machinations of the time.

The study's scope is not strictly confined to 1912-25, it rightly takes good account of contributory and background factors. It also has relevance for our current circumstances as many of the fears, grievances and suspicions which inform our political divisions are evident, if not sourced, in that period.

Tracing the history of a city against the background of the events which involved or affected the whole country proves, in this study, to illuminate the reader's understanding of both local and national history and the relationship between the two.

The impact of the developments of the time on Derry is strongly traced and Colin Fox shows how those experiences indelibly influenced political attitudes in the city. His study explores how the creation of Northern Ireland sentenced the city of Derry to become an affront to democracy through sectarian gerrymandering and a gross example of injustice in civic policy and public services, realising the fears of Derry's Nationalists at the time of partition.

This outstanding study is clearly written from a Nationalist perspective. That does not make it a partial study of the issues and events which the author chose to examine. Equally its Derry focus does not make it a parochial study or involve a loss of perspective on wider events. It will prove to be of value and interest not just to Derry people and not just to Nationalists. If anyone wants to improve their understanding of northern Nationalist perceptions they will find this book insightful.

Such insight in itself would make the book worthwhile. But the

inescapable resonances between events then and now give it an

even more profound relevance. We can all learn today from work

like this which offer a clearer understanding of another period

of serious mistakes in Irish history.

The purpose of this study is to examine the events and influences which contributed to the Nationalist majority of Derry City's population being converted to an electoral minority. It will look at the general and the specific factors involved. One main theme will be to analyse the factors and events that resulted in what Nationalists saw as their abandonment by the Provisional Free State Government and the English Liberals.

The study will also look at the change in Derry's relative position from one of pivotal importance in the political equilibrium of nine-county Ulster, to its relegation to the periphery of Northern Ireland, politically and economically.

While the specific area of study is 1912-25 it is essential to strive to detect those earlier trends and influences in the nineteenth century and how they eventually impacted upon the Nationalists of the North. In this respect the role of the Catholic Church and the rise of cultural Nationalism with its effect on the two traditions of Irish Nationalism, the revolutionary and the constitutional, will also be explored.

Direct attention will be given to the significant events of 1912-25,

the founding of the UVF, the Irish Volunteers, the 1916 Rising,

the Anglo-Irish War, the Treaty and the Civil War, and how they

influenced the ultimate partition of Ireland. This study will

also attempt to trace the origin of partition as an issue, and

its ruinously divisive effect on Northern Nationalists, precisely

at a time when a cohesive stance was imperative in gaining them

a more secure future. At all stages, the study will endeavour

to show how the impact of events in general affected or influenced

the politics and ambitions of Derry Nationalists.

Few would dispute the proposition that the years 1918-21 were one of the most momentous periods in Irish history. This period included the installation of the first Dail, the Anglo-Irish Treaty, the eventual political supremacy of Sinn Féin throughout Nationalist Ireland, and above all the partition of the country into two states. This was followed by a civil war in the southern state, which was instrumental in shaping the format of its political parties to the present day, and whose impact on the north for both Nationalists and Unionists was mainly negative. Critically the civil war gave the Unionists in the north and the British Government a freer hand in setting in place the structures of Northern Ireland, ie police, education and local government with, the minimum of interference from southern politicians or the IRA. By then events had moved to a stage where northern Nationalists were losing any power to influence affairs, whereas, formerly, Derry City had been a pivotal constituency in Ulster terms, and Joe Devlin of west Belfast had been one of the most effective leaders of the Irish Parliamentary Party.

In early 1917, the release of prisoners had brought increased political activity on the part of Sinn Féin. They used their status as the "revolutionaries of 1916", who had fought and died for an independent republic, to very effectively exploit the natural fears of conscription by arguing that without the Rising, conscription would have been implemented. This was a forceful point, and carried great conviction among an apprehensive electorate. Sinn Féin tested their political strength in by-elections, firstly in North Roscommon and South Longford where they won convincingly. It was noted by Inspector General Byrne in his comments to the Under Secretary that 'the conscription policy has captivated the Nationalist youth of the country. Although many of the older converts to Sinn Féin are not Republican it is evident that even they now expect a more ample measure of Home Rule than provided by the existing act.' [1]

There were further by-election victories in East Glare (for De Valera) and Kilkenny (Cosgrave) which gave even more momentum to Sinn Féin's growth. In contrast, County Inspector Cary of Derry remarked in July 1917 that Sinn Féin was not making any headway in Derry City, though Sinn Féin flags had been displayed in County Derry.[2] By enforcing Defence of the Realm Act Regulations some Sinn Féin activists and leaders had been imprisoned, notably Thomas Ashe (the commander of successful operations in Ashbourne in Easter Week). Ashe went on hunger-strike as a demand for political status within the prison, and died as a result of forced feeding on 25 September 1917. The IRB and Sinn Féin masterminded his military funeral as a national demonstration of mourning and protest, taking over most of Dublin without interference from the army or police. Significantly, Michael Collins delivered a short panegyric in Irish and English following the volley of shots over the grave side:

Nothing additional remains to be said. That volley which we have just heard is the only speech which it is proper to make over the grave of a dead Fenian.[3]This illustrates the sharp contrast in style between the pragmatic Collins and the semi-mystical Pearse over O'Leary's grave. The effect of the death of Thomas Ashe and his funeral was to re-invigorate the Irish Volunteers, and confirm the "spirit of 1916".

By August the first Sinn Féin Club had been formed in Derry City, calling itself the P H Pearse Sinn Féin Club, and set up rooms in Richmond Street. While there had been a lack of interest in Sinn Féin in Derry City as already indicated by RIC Intelligence reports, other factors began to influence the Nationalists of Derry. Although Sinn Féin, ignored the realities, viz, northern anxieties about partition, they made political gains from the collapse of Home Rule negotiations in 1916 and later from the eventual failure of Bishop McHugh to achieve any national recognition for his Anti-Partition League. This discrediting of constitutional Nationalists meant a partial drift to Sinn Féin, at least among the extremists, with only the Ancient Order of Hibernians staying loyal to their president, Joe Devlin. Sinn Féin's anti-conscription stance grew in support among the young and their parents, as news of the slaughter and mounting casualties of the Great War became grimmer. They continued to ascribe the absence of conscription to the Rising and graphically assured the people 'that but for Easter Week their bones would be manuring the fields of Flanders.'[4] Another influence was the succession of Sinn Féin victories in by-elections in the south, especially East Clare for De Valera, which gave rise to the first widespread national displays of public sympathy.[5] While it is true to say that Sinn Féin's following undoubtedly increased in the North, it did not, particularly in Derry City and west Belfast, replace the people's attachment to constitutional Nationalism for reasons that will become clear.

On 2 September 1918, a public Sinn Féin meeting was held in St Columb's Hall addressed by Eoin McNeil and L Ginnell MP. It attracted an audience of 2,500 who, in the opinion of the County Inspector RIC, were there 'mostly from reasons of curiosity.' In confirmation he noted that only ten of the audience returned completed membership applications. More Sinn Féin Clubs were formed in the Swatragh and Magherafelt districts.[6]

In April 1918, the British Government, severely haemorrhaging in man power terms, indicated that the new Military Service Bill would include conscription in Ireland of all men of military age (which they intended to raise to 50). There was a spontaneous outcry from all shades of Nationalist opinion in Ireland, bitterly repudiating England's right to enforce conscription on Ireland. An all-party conference was arranged for 18 April in the Mansion House, Dublin, comprising Sinn Féin, the Irish Parliamentary Party and Irish Labour, to consider the conscription crisis. On the same day a conference was to be held at Maynooth of the Catholic hierarchy under the presidency of Cardinal Logue. The Mansion House conference convened at 10.00am, the Maynooth one at 12.00 noon breaking 2.00pm for lunch, at which time delegates from the Mansion House conference arrived to attend the afternoon session. The Maynooth conference, with the support of the visiting delegates, issued a clear and very strong directive on the conscription question. They condemned any attempt 'to force conscription on Ireland against the will of the Irish nation' and went on to say:

...we consider that conscription forced in this way upon Ireland is an oppressive and inhuman law which the Irish people have the right to resist by all the means sanctioned by the Law of God.[8]The intensity of the opposition and the solidarity between the constitutional parties and Sinn Féin, allied with the support of the Catholic Church, was enough to forestall any imminent moves on enforcement of the New Military Service Bill. Predictably, reactions to this issue appeared to break down into party lines with Unionist papers supporting conscription, it was felt by opposition parties, mainly to embarrass the Nationalists.

At a packed anti-conscription meeting in St Columb's Hall in Derry, councillor H C O'Doherty pointed out that 'one good thing that emanated from the Irish Convention was that Nationalists and Unionists unanimously passed a resolution advising the government to avoid conscription in Ireland.' [9] It was accepted in Ireland that most rank and file Unionists opposed conscription. A dramatic example was given by a large parade and meeting at Ballycastle arranged by Nationalists and Unionists to protest against conscription. A procession was held before and after the meeting made up of Orangemen, Hibernians and Sinn Féiners who marched alternately to such tunes as "The Boyne Water" and "A Nation Once Again". The meeting was addressed by Louis J Walsh (Sinn Féin) and Mr W J Smyth (described by the Derry Journal rather starkly as "a Protestant"), the latter demanding that their cry be the same as the Belfast shipbuilders who said "We won't have conscription".[10]

However, Derry District Council No.2, in this sea of unanimity was an island of defiant partisanship. A motion condemning conscription was opposed by Mr T A McElhinney who maintained the 'Nationalists of Ireland had remained at home falling into the good jobs vacated by Ulstermen who went to serve their King and Country."[11] This was to highlight again what had been a running and bitter dispute throughout the war relating to recruitment figures. As early as March 1915 Redmond had maintained that of the 100,000 recruited to that date, 20,000 had been Irish Volunteers and 23,000 Ulster Volunteers and if Britain and the Colonies had been included there were then 250,000 Irishmen in the war. In August of 1918, the Derry Journal quoted figures given to Mr Joe Devlin (in reply to a written question) which he had received from the Under Secretary of War in April 1918. These figures showed that the total recruitment figure for Ulster was 58,000 of which 20,000 were Nationalist, proportionate to their percentage of the population. Furthermore, in the same answer it was revealed that the rest of Ireland recruited 65,000 of which 10,000 were probably Unionist, therefore according to official government statistic 75,000 Nationalists had joined the army, while the total number of Unionists was 48,000. This, Devlin submitted, once and for all exposed the lies and propaganda emanating from both Ulster and England that Protestant Ulster had given everything and the rest of Ireland, nothing. In proof of Devlin's allegations about propaganda, this section of his speech was reported solely in the Nationalist press.[12]

As the war ended, 11 November 1918, expectations of a settlement to Home Rule and a general election were high. The General Election was indeed called for December. Derry City's Sinn Féin Club had in September already nominated Eoin McNeill as their candidate, much to the resentment of local Nationalists who deplored the precipitate, unilateral action. While Sinn Féin had been clearly victorious in by-elections in the three provinces other than Ulster, the exception being Arthur Griffith's election in Cavan, and had made substantial political gains from their anti-conscription policy, Ulster had a crucial extra political dimension, partition. An indication of this had been earlier shown in the South Armagh and East Tyrone by-elections, in January and April respectively. These constituencies were in the Archdiocese of Cardinal Logue, who influenced voters against Sinn Féin and its revolutionary politics.[13] Partition was a critical issue, which Sinn Féin evaded by throwing the cloak of Republican independence over their own misunderstanding of its complexities. In the event, constitutional Nationalists, with good candidates, won both seats and so made Sinn Féin less dismissive of a pact in the eight northern seats, which they would not have contemplated otherwise. These victories appeared to establish that in the north the main issue was partition.

After some local wrangling in northern constituencies, it was clear that there were genuine fears of the northern seats being lost to Unionists due to a lack of unity among the Nationalist parties. This was a reflection of the traditional northern fear of factionalism in the face of strong intransigent Unionism. In Derry there was grave disquiet among Nationalists at Sinn Féin's unilateral and precipitate nomination of Eoin McNeill, though Sinn Féin felt confident enough in their support to ignore the attacks of the now politically discredited Bishop McHugh.[14] The leadership of Sinn Féin tended to be lower middle class, shopkeepers, publicans, clerks, with a sprinkling of professionals, teachers and lawyers. They particularly drew support from the young and even active sympathy from younger Catholic curates in Derry and Donegal.[15] As a result of pressure from Cardinal Logue and northern bishops, Dillon and De Valera, later replaced by Eoin McNeill, met to arrange a pact for the eight northern seats. Eventually, Dillon and McNeill agreed on 3 December to an equal division of the eight marginal seats and left the potentially contentious allocation of specific consitituencies to Cardinal Logue.[16] Derry City was assigned to Sinn Féin, where McNeill had already been nominated.

A public meeting of Derry Nationalists was held in St Columb's Hall on 11 December 1918 to demonstrate their unity and support for the pact candidate Professor John McNeill. Professor McNeill, in a wide ranging speech attacking the British government and the inconsistencies of the Unionists who condemned Irish Independence as dangerous to prosperity, began his speech by addressing the topic of proposed secularization of education by Sir Edward Carson and all that it implied for the North.[17] In making the education issue an important one he may well have been responding to the fears of northern Catholics as enunciated by Bishop McHugh in a letter to The Derry Journal on Friday 6 December. His lordship greatly feared losing the clerical stewardship of the schools, which his laity had built and paid for and moreover was alarmed at handing them over to those who were 'overtly hostile to every Catholic sentiment.' He continued by expressing concern about divorce being available in the six counties, and bequests for masses no longer being legal as charitable offerings; he also donated £10 towards Professor McNeill's election expenses.[18]

Councillor H C O'Doherty also spoke at the St Columb's Hall meeting and pointedly referred to the important role played by Irishwomen who had suffered great emotional loss in the emigration of the young for generations H C O'Dohertry was the only speaker that night to show any political awareness of the fact that the newly passed Representation of the People's Act had meant a revised poll, enfranchising women for the first time. This was particularly significant for Derry, which had drawn many women of all ages from Donegal and County Derry into its shirt factories for the previous forty years, resulting in a gender imbalance which had militated against Nationalists in previous elections. Indeed it was largely due to the traditional generosity of these women that the Derry churches and schools, over which Bishop McHugh agonised, had been built. McNeill's success was to a large degree attributable to this revised poll (Derry's electoral roll had gone from 6,000 to 16,000). Rev L Hegarty, who chaired the victory meeting for the new Derry MP, referred to this when he specifically congratulated the women of Derry for their contribution to McNeill's election.[20]

Women from Donegal and County Derry made up the bulk of the work force in the city's shirt factories.

Sinn Féin had swept the country, making the Irish Parliamentary Party an irrelevance (in which direction they had been moving since September 1914). They took 73 seats with their president in Lincoln Gaol and 33 imprisoned elsewhere, while the Irish Party only held West Belfast and Waterford, apart from the four Ulster pact seats. Joe Devlin, held in great affection by his own constituency, had easily defeated De Valera in West Belfast, by 8,488 to 3,245. John Dillon, the Irish Party leader, had been heavily defeated. However this was not a nationwide conversion to revolutionary politics, but rather in the main a collapse of confidence in the Irish Party's ability to deal with the Liberal Government and two consecutive coalitions.[21] Disillusioned Nationalists were now seeking a more determined leadership that would get them better terms. Most constitutional Nationalists could not have remained unaffected by the Easter Rising and its aftermath, and the anti-conscription issue had carried them even further from their relatively moderate positions. In Deny the failure of Bishop McHugh to gain national support for his Anti-Partition League had added to local Nationalists' disillusionment.

When the new Dail convened in the Mansion House on 21 January 1919, the 27 Sinn Féin Representatives still "at large" listened to a reading of the "Provisional Constitution of the Dail" followed by "Ireland's Declaration of Independence" and the "Democratic Programme of Dail Eireann" which was unanimously adopted. These institutions and programmes were regarded as theoretical by Collins and his TRB activists who considered their priority as expelling the English first and dealing with administrative matters second.[22] Partition as an issue and strategies for addressing it were barely mentioned. It is worth calling attention to part of the speech of Richard Mulcahy which has layers of future irony for later generations of northern Nationalists:

A nation cannot be free in which even a small section of its people have not freedom. A nation cannot be said to live in spirit or materially while there is denied to any section of its people a share of its wealth and the riches that God bestowed around them.[23]The main plank of Sinn Féin policy at this time was to seek recognition for Dail Eireann at the Peace Conference in Paris.

Throughout 1919, the post war slump caused labour turmoil in Britain and Ireland. As most union activists in the south were Sinn Féin, this created tensions in the movement, particularly among farmers who did not welcome incessant wage and conditions demands from their labourers.[24] The General Strike spilled over into Belfast and involved workers who were united in non sectarian solidarity. In Derry however a branch of the Ulster Labour Association had been formed in advance of a mass meeting of workers at the Guildhall in February. It had been founded by Sir Robert Anderson, shirt manufacturer and defeated Unionist candidate, which reflects the extent of its radicalism. The obvious purpose, of course, of this association was to reassure Protestant workers of job security and future job patronage on condition they did not join with fellow Catholic workers in radical organisations such as Trade Unions. The ruthlessness of Protestant employers in dealing with Protestant union activists had a salutary effect on the workforce, already subject to the pressures of high unemployment. The timing of Sir Robert's setting up of his Unionist Labour Association was designed to undermine the mass rally at the Guildhall on 19 February. While there was a lot of militant rhetoric at this meeting it was decided that a ballot would need to be taken on direct action, which in effect was a postponement and thereby disheartened the radical activists.[25] The Union situation in Derry had not been helped by the actions of Peadar O'Donnell, IRA man and ITGWU organiser, who himself admitted in 1983:

the ITGWU entry into Derry was a mistake and ultimately divisive. Unionisation in Derry was already adequate and the ITGWU's identification with Irish Nationalism in Derry coincided with the outbreak of hostilities between the IRA and Britain, and only served to heighten divisions between workers of different political and religious persuasions.[26]The Carter's Strike of March 1919 which was bitter and non-sectarian was defeated when it succumbed to the endemic pressures of sectarian vested interests.[27] Added to the labour unrest had been the commencement of the Anglo-Irish war, which is considered to have begun with the shooting of two RIC men at Soloheadbeg in Tipperary on the same day the new Dail convened. With the eventual failure of the Dail delegates to attract any support at the Versailles Conference, it now appeared to Sinn Féin that Irish Independence would have to be won in Ireland, not in Paris or Westminster.[28] From April the IRA military campaign intensified.

In Derry the Unionists Party continued to administer the city from a gerrymandered council while the P H Pearse Sinn Féin Club pledged its support to the Sinn Féin candidate in the North Derry election, which resulted in an increased vote for the Republican Patrick McGilligan. This was evidence that northern Nationalists still hoped Sinn Féin would be an effective defender against inclusion in the six counties.[29] The military campaign of the IRA south and west combined with the tension in awaiting some form of settlement was creating dangerous undercurrents. The apparent inability of Dublin Castle to deal with the situation was producing in all Nationalists an expectation that independence was inevitable. This sense of Nationalist unrest expressed itself in Derry on 15 August when the traditional Nationalists parade demanded the right to walk on Derry's Walls. This resulted in a serious sectarian riot, necessitating army intervention to help the police.[30] This particular incident serves to show the extent to which religion and politics had become inextricably linked in Ireland, since the relationship between the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin and Derry Walls can only be at best, tenuous.

On 12 September Patrick Shiels, a Derry IRA leader and Sinn Féin activist, was arrested for allegedly threatening the police with loaded revolvers during a house search. The P H Pearse Sinn Féin Club had left its Richmond Street, premises under threat of eviction in October, and by December had been refused temporary accommodation for their meetings by the AOH and the United Irish League." This revealed how brittle and ambivalent was the liaison between Sinn Féin and Derry Nationalists where other issues were more relevant than in the south. There was also some degree of tension and unease within the Sinn Féin Executive itself which was recounted in RIC Intelligence reports which stated:

A reliable informant states that a split has occurred in the Sinn Féin Executive. He states that at a meeting in Dublin on the eve of the suppressed Ard Fheis, Messrs. John McNeill and James O'Meara MP's, deprecated the murders and outrages committed throughout the country which they alleged the public attributed to Sinn Féin. Some of those present protested against the introduction of such matters and a stormy scene ensued.[32]Sinn Féin and the Nationalists, at the end of September were concentrating their energies on revising the political register for the 1920 Municipal Elections. There is no doubt that the bulk of this work was done by Nationalists, who had built a formidable lore of local electoral information aided by the very effective veteran election agent Michael McDaid.

Meanwhile, throughout 1919, the British Government had been working on how to replace the ill-fated 1914 Home Rule Act, then still in suspension. By November most Nationalist politicians anticipated that some form of partition would be advocated. In the event, Lloyd George's provisions in the Government of Ireland Bill 22 December 1919 allowed for two parliaments, one in six-county "Ulster" and one in the 26-county South. It also proposed a Council of Ireland composed of twenty representatives of each parliament, which could eventually, without reference to Westminster, be converted into an all-Ireland Parliament.

Sir James Craig had dissuaded the Committee on the Situation in Ireland from setting up a nine-county state but settled for the six-county option as containing a more manageable Catholic minority. The Catholic minority in nine-county Ulster was 43.7% but in the six counties was only 34%.[33] (Significantly the 43.7% deemed as "unmanageable" by Craig was almost exactly the Catholic percentage of the six county population in the 1991 census.) This Government of Ireland Bill slowly worked its way through a parliament virtually devoid of any Nationalist representation due to the Sinn Féin abstentionist policy, and eventually received the Royal assent on 23 December 1920 to become the Government of Ireland Act. Nationalists still felt that this legislation had an air of unreality and believed it would not be enforced.

In mid January the municipal elections were held under Proportional Representation terms introduced by the British Government in a ploy to minimalise the Sinn Féin vote. It had the opposite effect in the North, where both Sinn Féin and Nationalist coalitions polled very strongly. The municipality of Derry City had been gerrymandered but Nationalists felt that with a well-maintained electoral register they had a good chance of winning. Many demonstrations of Single Transferable Voting were held in local halls to ensure the minimum of confusion. The seasoned Nationalist registration agent, Michael McDaid, and Patrick Shiels of Sinn Féin (until his arrest) had both worked vigorously in the Revision Courts where objections to votes on the register were heard. There was strong motivation among all Derry Nationalists to make a show of strength in response to the introduction of the Government of Ireland Bill on 22 December 1919. This they did achieving a historic victory of 21 seats to 19; the maiden city had finally fallen to Nationalists. Omagh had also been won by Nationalists, and Limavady Council saw Nationalists winning seats for the first time. The effectiveness of both Derry political machines, Nationalist and Unionist, to maximise their respective votes was legendary throughout the British Isles, as was the constituency's renown for close contests. Moreover, in applying their well-honed skills to PR, their efforts were proved supreme in Ireland, when in May 1920, they ranked in the Journal of the Proportional Representation Society as having the least percentage of spoiled votes. The North and South Wards both had the highest poll of 93.5%. In Ireland as a whole there was a very low percentage of spoiled votes (2.79% to the apparent surprise of both the British and Irish press), with the North Ward in Derry having the smallest percentage (0.68%) of spoiled votes.[34] The welcome victory for Nationalists was further amplified with the installation of a Catholic mayor on Friday 30 January 1920. The main issues in the election from the Nationalist viewpoint had been asserting Nationalist commitment to a united Ireland, education and housing, as Derry had been experiencing what local papers referred to as a housing 'famine' with many families living in cramped and unhealthy tenement conditions. They therefore saw a victory in Derry as making partition more difficult, or in the last analysis a Derry "opt-out" from the six counties more predictable.

Alderman Hugh C O'Doherty, a local solicitor, former supporter of Pamell and an articulate constitutional Nationalist was the first Catholic mayor of Derry City since Cormac O'Neill, who had been appointed by James II shortly before the Siege and who held office only for a short period.[35] Mayor O'Doherty, in his opening speech, emphasised the historical nature of his accession to the Mayoral chair. He went on to ask the Protestant politicians and citizens of their ancient city to be realistic in this time of change and directly appealed to them:

Is it not time that you reconsidered your position in relation to your countrymen; that you came to the conclusion that you owe your allegiance to this land of your birth, and that you should no longer play the part expected of you by English politicians but join with your fellow-countrymen in demanding that the government of this country shall be by Irishmen in the sole interests of Ireland.[36]Alderman O'Doherty also proposed that the flying of all flags on the Guildhall be prohibited thus ensuring that no citizen be deterred from identifying with his council. He also announced that he would not attend any function where a loyal toast was made or any formal recognition of the British Government was implied. He later had Lord French's name withdrawn from the list of Derry Freemen, on the grounds that he was overtly hostile to the majority of the city's citizens.

H C O'Doherty, the first Catholic Mayor of Derry since Cormac O'Neill

during the time of James II. (Photograph: O'Doherty family)

Derry Nationalists now felt that they had made substantial gains and were already, to some degree, tasting the fruits of independence. Their victory was a boost to the morale of all Northern Catholics. The Irish News maintained that the loss to the Ascendancy of the maiden city signalled the end of partition as an argument.[37]

Within a few months the feelings of jubilation were to turn to those of alarm as Protestants commenced armed attacks against Catholics. There were serious riots on Saturday 16 April which lasted for hours, culminating in an armed attack by Nationalists on Lecky Road barracks during which at least six civilians suffered gunshot wounds.[38] In a later incident a young Catholic was shot by Protestants at Carlisle Square. [39] The Derry Journal found evidence of careful planning in relation to the attack on Lecky Road barracks. This points to the conclusion that this was the first clear IRA offensive in Derry. [40] The Derry Journal also traced the origin of the riots to an attack by soldiers of the Dorset Regiment opening fire on a Catholic crowd in Bridge Street consisting mainly of youths, women and children. The following Saturday night two soldiers passing along the top of Bridge Street were attacked by youths in reprisal, leading eventually to a full scale riot. [41] Around the middle of May another more serious riot occurred, when armed Unionists invaded Bridge Street firing revolvers and throwing stones, in retaliation, they maintained for the shooting of a clergyman in County Down. In the course of the ensuing riot many revolver shots were exchanged from both sides, and after a bayonet charge down Bridge Street, Sergeant Mooney, head of Derry Special Branch, was shot dead on Derry Quay. This again, by the prevalence of weapons in the Bridge Street area, appeared to be an IRA action. Protestant masked and armed gangs from the Fountain Street and Wapping Lane area took over Carlisle Road and commandeered the end of Carlisle Bridge, assaulting and threatening Catholics. [42] Later, a young ex-soldier from Anne Street, Bernard Doherty was shot and killed by Unionists in Orchard Street. The reporting of these earlier incidents serves to show that Derry's June 'riots' or 'war' were not as implied elsewhere the result of an isolated incident in the middle of June but were the culmination of months of armed intimidation by Unionists from the Fountain Street and Wapping Lane area, who appeared, to operate around the area of Carlisle Road/Carlisle Bridge with impunity, under the eyes of an apparently complaisant police force and army. While the leadership of the IRA were later to assert that they did not involve themselves in sectarian conflict, they had certainly on occasion adopted at least a defensive role eg in the Bridge Street area, and an offensive one as recorded already in the attack on Lecky Road police station.

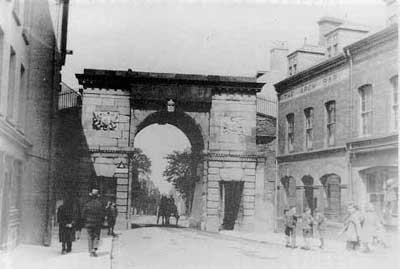

Bishop's Gate, scene of skirmishing and shooting during the June riots, 1920. (Photograph: Magee College)

The June episode of rioting, which eventually degenerated into what became known as "Derry's Civil War" began on Sunday 13 June when an excursion party of Nationalists was attacked and fired on by armed Unionists in the Prehen area of the city. [43] The armed men were mainly ex-soldiers from the Fountain Street! Wapping Lane area who frequented the Prehen Wood to indulge in drunken horse-play, no doubt away from the disapproving gaze of their Presbyterian brethren in the Fountain area. There were further attacks on the following Monday and Tuesday nights, with long exchanges of fire between gunmen in the Fountain Street and Bridge Street area, revolver shots being heard from the Nationalist Bridge Street and predominantly rifle fire coming from the Unionist Fountain Street. [44] On Friday 18 June, armed Unionists in the Waterside area of Derry invaded a Catholic district, Union Street and Cross Street, driving out residents, wrecking houses, looting shops and generally creating havoc. The Derry Journal of 21 June 1920 recounted the aftermath:

On Saturday morning these thoroughfares, Union Street and Cross Street presented an appearance as if an avenging army had passed through them, so great was the destruction caused.The attacks had commenced at 10.00pm and continued until six the next morning, with Unionist reinforcements marching across the bridge during the night. Attempts to rescue the unfortunate residents by boat from the other side of the Foyle were repulsed in an exchange of rapid revolver fire. Residents of the Cross Street area reported that "men in military uniform took part in the attack".[45] The night long devastation and mayhem in Cross Street and Union Street took place only a few hundred yards from Ebrington Barracks, the base of the Dorset Regiment. This raised the atmosphere in the city to a dangerously inflammable level. On Saturday night troops and police took up positions in the usual flashpoint areas, Carlisle Square, Bridge Street, Fountain Street and Wapping Lane hoping to deter an expected riot, or possibly to defend the Protestant areas from reprisals. However, the riot developed that evening in an unexpected area, after a drunken squabble when a revolver was allegedly drawn. This was at eight o'clock at the junction of the Catholic Long Tower Street and the Bishop Street end of Fountain Street. At nine o'clock Unionists poured rifle and revolver fire into Long Tower Street. The first man killed was James McVeigh, a sixty year old resident of Walker's Square whose three sons had served in the army, one having been killed in France. That night five men were shot - four Catholics and one Protestant. [46] Though firing into the Long Tower Street district had commenced at 9.00pm, a strong detachment of the Dorsets did not arrive until 11.00pm, when the Unionists finally withdrew to Fountain Street. The disorder had spread to William Street, a predominantly Catholic area, where some looting of Protestant owned businesses began. At this stage the Irish Volunteers intervened and patrolled the area with hurley sticks. [47]

There was a lull on Sunday, but the following Monday armed Protestants openly patrolled Carlisle Square, controlling access to Carlisle Bridge and Carlisle Road. That evening, 21 June, they again attacked Bridge Street. On this occasion, as the shooting began to spread to other areas, it prompted the first appearance of a body of Irish Volunteers carrying service rifles, who deployed themselves from Butcher Street firing into Unionist areas. As a result of this apparent threat, an armoured car was quickly dispatched to the Diamond to drive out the Volunteers, but street fighting continued on a widespread scale. Two more Catholics were killed, as well as Howard McKay, the son of the Governor of the Apprentice Boys. [47] Armed patrols now routinely protected the fringes of their respective areas, interrogating, searching and occasionally firing. Sandbagged defences were much in evidence at flashpoints. The reporter of The Irish Independent was in no doubt of the scale of the conflict saying:

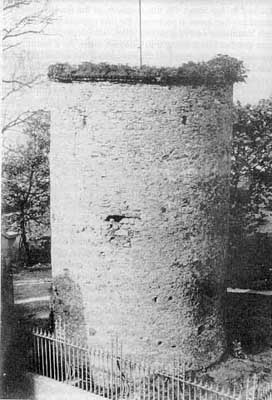

...the term 'rioting' does not give an adequate idea of the situation. It was war pure and simple. For the last few days Orangemen have more or less dominated the situation, but it was indicated on Monday that their domination was no longer maintained. [48]The same Monday night attacks had been made on the Bishop Street area by Protestant gunmen from Abercorn Road and Barrack Street, with fire concentrated on St Columb's College. When the President of the College asked for assistance in defence of the College, after it was again attacked the following night, the Irish Volunteers assumed responsibility for its protection and the surrounding area. [49] They dislodged Protestant snipers and inflicted substantial casualties, estimated at twenty. At this point the Commandant of the Irish Volunteers issued a proclamation 'that in consequence of the authorities having failed to maintain order they would have to take control of the situation.'[50] They declared that until then they had avoided entering into what was purely a sectarian quarrel but events had reached a stage when they considered it their duty to interfere. [51] With the effective defence of St Columb's and the obvious assertiveness of the Volunteers, resulting in many Protestant casualties, the shooting dwindled, and the British Army intervened on Wednesday afternoon, 23 June. Due to the partisan behaviour of the army in openly fraternising with armed Unionist killers and looters, some RIC officers threatened to resign and complained bitterly to the military authorities. [52]

Round tower in St. Columb's College grounds, the scene of fighting between IRA and UVF in June 1920.

(Photograph: Magee College)

Eoin McNeil, the Derry TD, had returned to Derry to assess the situation and recorded his reaction in his memoirs:

When I arrived in Derry... there was a barricade across the public thoroughfare facing Victoria (sic) Bridge. and another of the same kind from side to side across the principal street of the town, William Street. The town was left completely in the hands of the Orange Mob... I went to the Catholic College and lodged there... I saw the windows that had been shattered with bullets. By the time that I came on the scene affairs had taken a turn which I will describe and the British military had come out into the street. In one of those houses a child put its head out of a sky light in the roof and was promptly shot dead by one of the soldiers. This was the only attempt my memory records on the part of the British Government to preserve the King's peace in the city of Derry...McNeill's biographer, Tierney, also refers to the claim that "the small body of Volunteers" to which McNeil refers was popularly believed to be an active service unit sent by Collins from Dublin and the memory of their marksmanship was to last for many years. The writer however can find no evidence for this anywhere, but plenty of contrary evidence from local press accounts, and oral accounts of Derry residents at the time, who were indeed able to identify some of the "marksmen", such as Shiels, Fox, Kavanagh, Doherty, McDade and Brady who were also recognised Commanders, and these were joined by several Nationalist veterans of the trenches of the First World War. The latest evidence of this was in the recollections of George Hamill, a well known Derry Union Official in The Derry Journal of 19 May 1995. [54]A small body of Irish Volunteers from Derry got together about a dozen of his comrades and threw up a small barricade.., they began sharpshooting against the assailants in various buildings. The resistance gave rise to the rumour that Volunteers were marching in a body from Donegal to enter the city. [53]

The IRA had organised the arming and watch duties of the defenders of their areas. Food had been commandeered and supplied to needy families in danger zones, on one occasion a cow being slaughtered in the local abattoir and each family receiving 2lbs of meat. This indicated a good measure of organisation by the IRA and reflected much local support, not surprising considering the nature of the crisis. The one decisive feature to emerge from their confrontation with the UVF was that they were not sufficiently armed to engage in sustained conflict, but should rather rely on superior guerilla tactics and strategy. However the readiness and vigour with which they defended appeared to have ensured that armed Protestant mobs were never to attack Catholic areas in Derry again.

Peace resumed in Derry after that, and several prominent Protestant businessmen publicly thanked the Irish Volunteers for protecting their property, and likewise Captain Wilton was publicly appreciated by Catholics for defending their property from Protestant looters. This lends weight to the theory that the Protestant murder campaign emanated from elements within the Fountain Street area and was not initiated or endorsed by the Derry Unionist leadership. These Fountain Street elements were believed to have been violently reacting to the Catholic assumption of power at Corporation level. [55]

The death toll had been 19 (15 Catholics and 4 Protestants) with countless injured. It was also believed by Nationalists that Protestant dead had been buried secretly during the height of the conflict, though no evidence of this has ever emerged. [56]

An unfortunate sequel to the Derry "riots" ensued in Belfast. Some Protestants fleeing Derry arrived in Belfast, and one of them addressed a meeting at Workman & Clark shipyard inflaming Protestants to attack their Catholic workmates. This was to begin the expulsions of Catholic workers in Belfast. Later that summer and the following year there was wholesale burning, looting and killing by armed Orange mobs, with the involvement of the UVF, and thanks to inflammatory speeches by Edward Carson and misleading news reports in The Belfast Newsletter. In total, from July 1920 to August 1922, the Belfast pogroms accounted for the deaths of 453 (257 Catholic), the driving out from their homes of 23,000 Catholics, and expulsion from their workplaces of 11,000 (from a population of 90,000). All Catholic families had been expelled from the towns of Lisburn, Banbridge and Dromore. [57] It was also estimated that 50,000 Catholics fled the North to the South, England and Scotland. [58]

There can be no doubt that Unionists, fearing that the success of the IRA in the South and West might result in a compromise on the six counties, were inflamed by irresponsible politicians and press, and decided to "consolidate" Protestant areas and workplaces, though initially this may have been a defensive reaction. The view of Eoin McNeil was that Protestants were trying to produce a more homogeneous Protestant Ulster.

In the county elections of June 1920, Fermanagh and Tyrone had passed to Nationalist control indeed throughout Ireland, the Unionist controlled only four counties and some of those only with small majorities. As in the 1918 elections it proved the fallacy of the Protestant claim that there was a Protestant homogeneous six counties, as even so-called Protestant areas had substantial Catholic penetration.

With the Truce in July 1921 and consequent talks between De Valera and Lloyd George, the Nationalists in the North became anxious about their position as a result of any discussions. The Government of Ireland Act had come into force in April 1921 and on 7 June the new Northern Ireland Parliament assembled in Belfast City Hall. On 22 June King George V arrived for the State Opening. While Nationalists openly derided the Belfast Parliament, partition was beginning to assume a dangerous air of reality. The Northern Ireland Government looked like it was establishing itself. Lloyd George offered De Valera dominion status for the 26 counties which De Valera refused but offered instead the idea of "External Association". This meant in effect that Ireland was not in the Commonwealth but loosely associated with it by one of De Valera's famously semantic threads.

The anxieties of Northern Nationalists were further compounded by the continuation of the Belfast pogroms, with murder and population displacement continuing apace. An indication of the degree of Nationalist disquiet was demonstrated by the series of delegations during September and October that went to the Dail on behalf of all geographic sections of six-county Nationalists. On 13 September 1921, a delegation on behalf of Derry City Corporation met with President De Valera "to protest at the exclusion of Derry from the rest of Ireland". Present at the meeting were Griffith, Childers and McNeil, the Derry TD. Alderman Bradley, acting as spokesman pointed out that:

Derry is the second city in Ulster and is by position, population and trade and industry, the capital of North West Ireland. It has the closest relations in business and other intercourse with Donegal from which the British Government proposed to separate it, at the same time separating Donegal from the rest of Ireland, and even from Ulster.In reply, President De Valera assured them that Dail Eireann would bear in mind the case of Derry City along with other regions of Ulster in any negotiations that might take place.[59] Significantly a month earlier, on 22 August at a private session of the Dail, when pressed by Louis Walsh (Sinn Féin) for a clarification of his Ulster policy, De Valera ruled out force because they lacked the power and 'some of them had not the inclination and moreover the policy would not succeed.' He was vaguely in favour of some form of county optout or plebiscite, for example by Tyrone and Fermanagh though Derry City was not mentioned at this stage. It was believed by some, including Lord Midleton, that Sinn Féin were particularly covetous of acquiring Tyrone and Fermanagh, where their party had taken the strongest hold in the six counties. [60]

The Anglo-Irish Conference opened on 11 October 1921 and the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed at 2.00am on 6 December 1921. News of the Treaty quickly spread to the press and to De Valera's abiding resentment, before he himself had been informed. By 7 December a deputation representing all shades of Northern Nationalist opinion had arrived in Dublin for a Mansion House Conference, seeking elucidation of the Treaty articles with reference to the six counties. Derry City was represented by Mayor H C O'Doherty and Father McFeeley PP Waterside. The Dail Speaker and Eoin McNeil outlined the policy they thought they ought to adopt. It constituted a combination of non-recognition of the Belfast Parliament with a practical programme of "passive resistance". He further asserted that 'the danger in the North is an artificial one although it is a real danger. It has not got the strength of permanency.'[61]

The Mayor of Derry, not noted as a dissembler, came quickly to the point:

Our representative has given away what we fought for over the last 750 years. It is camouflage. Once the Northern Parliament is put into operation there is a breach in the unity. We are no longer a united nation. You have nothing to give us for sacrifices you call upon the people to make. If in the first instance Belfast contracts out you are handing over manacled the lives and liberties of the Catholics who live in that area. There are no doubt suggestions of guarantees for the minority. What guarantees can be given to minorities in respect of the legislation, in respect of filling appointments. If they contract in, the position you hand to the Northern Parliament is that they have full legislative powers in the Act of Parliament that will enable them to gerrymander us out of existence as they have done from time immemorial. They will be able to fill every appointment. No guarantee is asked from them in respect of any of these matters. We will be ostracised on account of our creed.Both Dr McNeill and Councillor Shiels (Slim Féin) from Derry disagreed, again reflecting the tensions within Northern Nationalists due to the partition issue.

Father McFeely pointed out that:

Belfast would go in for secularising the schools. We could not work under a Belfast Parliament. We absolutely decline to have anything to do with the Belfast mob. We are not able to help ourselves. We want to know if anything can be done for us. This thing is now signed.Father McFeeley's cri de coeur held an accurate assessment of powerlessness of Northern Catholics when faced with a partisolution agreed by their own political representatives.

The next day, 8 December, spokesmen from the deputation met Valera at 11.00am in the Oak Room at the Mansion House. This minutes before De Valera was to oppose the Treaty at a critical cabinet Meeting that morning. To their requests for clarification De Valera replied noncommittally that he could not give them any advice but said the cabinet would be pleased to consider their views. Further pressed on the partition issue he continued:

Until a definite settlement is arrived at, we get on as we are doing; whatever was decided in the past holds good. Until the Northern Parliament is recognised by the Irish people it has no authority in our eyes.This has the characteristically cryptic note De Valera adopted n he confronted the topic of partition in particular, and the Treaty general. [62]

The Mayor of Derry's repudiation of the Treaty terms was not reflected in the views of The Derry Journal which saw the Treaty as "An inspiring Achievement" and like the Nationalists of Tyrone and Ferrmanagh saw Article 12. referring to the Boundary Commission, as a redemption from the Northern Parliament. [63] Lord Carson, venting his disappointment to the Upper House, maintained that Ulster had been betrayed, and that England had been made 'to scuttle out of Ireland' The signatories of the Treaty had been led to believe Boundary Commission would enact frontier changes excluding large Catholic majorities, "according to the wishes of the inhabitants" like Tyrone, South Armagh, and South Down and even Derry City. The effect of this, the signatories believed, would leave the remaining area no longer economically or politically viable, and so it would virtually drop into the lap of the Southern Government. (Significantly neither the Nationalists or Unionists paid attention to the amended version of the original Treaty relating to border changes arising "from the wishes of the inhabitants". The amendment added" so far as may be compatible with economic and geographic conditions".) The optimistic viewpoints on the Boundary Commission appeared to overlook the fact that the Northern Ireland Parliament was already putting into place the administration of education and local government, it had a large and well armed paramilitary police force paid for by the British Government, (Lloyd George later admitted he had armed 48,000 Protestants), [64] and the support of the British Army. It is unlikely that someone as pragmatic as Collins did not have this in mind. In conjunction with McNeil's policy of non-recognition and passive resistance, Collins advocated making the Belfast Parliament unworkable, and while negotiating further with Churchill and Craig had unleashed the Pro-Treaty IRA in the North. This resulted in murderous reprisals in Belfast and the Border areas. Collins' policy was a complete misreading of the Unionists, who, after all, saw themselves as having nowhere to go and thus reacted to attacks with greater determination to hold their existing border. Collins appeared to have contradictory views of the Ulster question. He wrote to Louis T Walsh about the position of Northern Nationalists:

…that we stand first in the unity of Ireland, second on the boundaries decided by the wish of the inhabitants. Until one or other is achieved, I have maintained there could be a solid anti-partition party (as one party) in the North East.The contradiction between the goal of unity and the acceptance of partition implicit in the Treaty made many Nationalists direct their hopes to Article 12 as their only release from an "alien dispensation". They had read about the Treaty debate devoting its most intense rhetorical energies to "the oath" and the nature of dominion status. They read of De Valera's Document 2, its amendments, and its final withdrawal in a haze of unintelligibility (though including an acceptance of the Boundary Commission solution) and remarked that out of 338 pages of debate printed in the Dail Report only nine were devoted to the question of partition, and six of those were contributed by three deputies from County Monaghan. [66] Some Derry and border Nationalists therefore sensed the utter unreality of the approach, or lack of approach of the provisional Dublin Government to the Ulster question. A cover of Republican rhetoric had been flung over its complexities and ambiguities to disguise the Southern incomprehension and! or indifference. Northern Sinn Féin conspired with the Dublin Government to sustain a policy of nebulous national unity that again contradicted the reality of Northern partition. Cahir Healy, a leading Sinn Féin supporter, was to admit in 1925 that 'the Sinn Féin leadership (1918-22) did not understand the Northern situation or Northern mind. Griffith, sanest and best informed of them, nursed a delusion that the beginning and end of the problem lay in London.'[67]

Nationalists in Derry now clung tenaciously to the Boundary Commission as their only hope, defeating a Sinn Féin proposal in January 1922 not to recognise the Belfast Parliament. Bishop McHugh had made a return to politics as Sinn Féin had lost ground in their inability to obstruct partition, and argued that Derry Corporation had to avoid abolition by the Northern Ireland Government, so that a Nationalist corporation would be in place to make a successful plea to the Commission for Derry's inclusion in the Irish Free State. However, a severe shock awaited the Derry Nationalists. In October 1922 the Northern Parliament abolished Proportional Representation, and proposed new municipal elections in January 1923 based on pre-1919 gerrymandered electoral boundaries. This change was designed to strengthen the Unionist case in relation to Article 12 as they could now hope to regain lost councils. In November at a public meeting in Derry, it was decided to boycott the elections. [68] A Unionist majority was returned in January's election and Derry Corporation reverted to Unionist minority control. Nationalist Councillors were not to return to the council for ten years.

In his final speech as the outgoing Mayor of Derry, H C O'Doherty angrily accused Craig of 'disenfranchising the minority and reducing its members to the condition of serfs.' In refusing Craig's request for Nationalists to attend the Belfast Parliament, Mayor O'Doherty vowed 'So far as I am concerned I will neither dip my beak into his dish nor feed out of his hand.'[69]

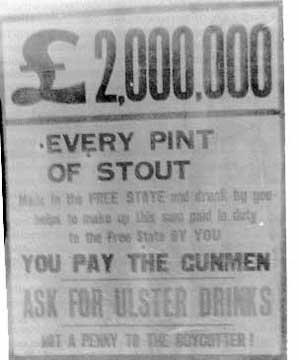

Poster urging the boycott of Irish goods. (Photograph: Magee College)

The situation for Northern Catholics had been further complicated by the Civil War, but not because the issues which divided the South weighed heavily with Northern Nationalists. The three way divergence of Nationalist policies (pact elections aside) had existed since the Belfast Conference of June 1916, with border Nationalists now exclusively seeking a solution through Article 12, the Belfast Devlinites seeking recognition of the Belfast Parliament as a united Nationalist front seeking better terms from it, and finally Sinn Féin, still adhering to the Dublin "unity first" line. The issue of Pro-Treaty and "Irregular" did not really arise, except within Sinn Féin and the IRA who in Belfast and Derry were mainly Pro-Treaty. (Frank Aiken of South Armagh was later to defect to the Anti-Treaty side.) The Civil War prevented the Dublin Government, from August on without Collins or Griffith, from giving much attention to the Ulster problem or the mechanics of the Boundary Commission, whose formation was now delayed. The loss of Collins and Griffith was particularly crucial to Northern Nationalists as they were the only members of the Dublin Government who gave any priority to their plight. The Dublin Government's pre-occupation with the Civil War thus afforded the Northern Ireland Government time to consolidate, as it proceeded to do in local government administration policing and education. This was also the period when the divisions and confusion of the Northern Nationalists dissipated their effectiveness and bargaining power in dealing with the Belfast Parliament. An indication of this was in their response to the new municipal elections in January 1923 when Nationalists in Derry City, Dungannon, Enniskillen and Downpatrick boycotted the polls while Armagh, Strabane and Omagh, who maintained their majorities contested, took part, thus presenting an appearance of disunity. It must be borne in mind, however, that Northern Nationalists had been subjected to great uncertainty, and political vacillation from the British Government since the failure of the Home Rule negotiations in 1916.

The last great hope of Derry Nationalists, the Boundary Commission,

was already beginning to fade after Unionists resumed control

of Derry Corporation in January 1923. Optimism was waning and

giving way to thinly veiled desperation. Due to further obstruction

by Craig and disarray in a Dublin Government recovering from the

Civil War, further delays were encountered in the setting up of

the Boundary Commission. This enabled the Northern Ireland Government

to further strengthen its administrative and territorial position,

to the detriment of Northern Catholics. The Commission finally

met on November 1924, the Irish Government representative being

Eoin McNeill, one time Derry TD. The Commission made a number

of visits to Derry with full hearings on Derry's position taking

place in the city from 14 May 1925 to 5 June. Evidence from both

Nationalist and Unionist sides was presented. The claims that

the city should become part of the Irish Free State were opposed

on the grounds that the greater part of the trade of the city

and its port was with Northern Ireland and that the city was linked

economically with the Protestant districts of the East. [72]

These last points were decisive for Judge Feetham, who invoked

the "so far as may be compatible with economic and geographic

conditions" clause of Article 12, maintaining that those

conditions would take precedence over the "wishes of the

inhabitants". This clause was used to the same effect in

all parts of Ireland. It was alleged by E M Stephens, Secretary

of the Northern Eastern Boundary Bureau, that Derry Nationalists

had mismanaged their presentation of their case, mainly because

'they seemed unaccustomed to working together. [73]

Irrespective of the truth of this observation, the fact that

all Nationalist areas were included in the six counties against

their wishes would make the quality of their submissions appear

to have been irrelevant. These findings relating to Derry were

leaked to the press, it is believed by Fisher, the British Government

representative, on 7 November 1925. In the resultant furore Eoin

McNeill resigned from the Commission on 20 November and from the

Southern Government a few days later. Eventually after much bargaining

and threats, Cosgrave was out-manoeuvred over spurious tax claims

and finally on 3 December 1925 signed the Tripartite Agreement

amending the 1921 Treaty. This accepted the Northern Ireland border,

the six counties, without qualification, and the virtual abolition

of the Council of Ireland, for Dublin's release from the concocted

tax claims. Cosgrave, to the everlasting bitterness of Northern

Nationalists, claimed that he had negotiated 'a damned good bargain.'

To the Nationalists of Derry and the border areas, who had supported

the Treaty on the grounds that Article 12 would release them into

the Free State, now stood abandoned, isolated from the hostile

Northern Government and now alienated from what they had once

viewed as the friendly Dublin Administration. Furthermore their

betrayal and internal exile in their fatherland, was intensified

by the lack of guarantee or security of civil rights as expressed

by Cahir Healy. [74] The words of H C O'Doherty to

the Mansion House Conference on 7 December 1921 now seemed prophetic

when he feared that 'they (Dublin Government representatives)

were handing over manacled the lives and liberties of the Catholics

who live in that area.' Derry's sense of agony and betrayal was

heightened and further refined by the experience of having seen

from the heights of municipal autonomy, the distant new Jerusalem

of National Independence only to fall into the chasms of treachery

and intolerance. The populous Nationalist majority was now a sullen

and disenchanted minority in its own city now part of that greater

disillusioned and demoralised minority of an intolerant, unyielding

hostile statelet, Northern Ireland.

Chapter Four

| 1. | RIC Reports Inspector General July 1917 CO/904 |

| 2. | RIC Reports County Inspector July 1917 CO/904 |

| 3. | Tim Pat Coogan - Michael Collins (Hutchinson 1990) Page p74 |

| 4. | RIC Reports Inspectory General August 1917 CO/904 |

| 5. | D Murphy.- Derry Donegal and Modern Ulster 1790-1921 p243. |

| 6. | RIC Reports County Inspector September 1917 |

| 7. | Derry Journal 8 April 1918 |

| 8. | Derry Journal 19 April 1918 |

| 9. | Ibid. |

| 10. | Ibid. |

| 11. | Ibid. |

| 12. | Derry Journal 5 August 1918 |

| 13. | E Phoenix - Northern Nationalism - Nationalist Politics Partition and the Catholic Minority in Northern Ireland 1890-1945 p46 |

| 14. | Desmond Murphy - op.cit., p251 |

| 15. | Desmond Murphy - op.cit., p246 |

| 16. | Eamon Phoenix - op.cit.. p51 |

| 17. | Derry Journal 13 December 1918 |

| 18. | Derry Journal 6 December 1918 |

| 19. | Derry Journal 13 December 1918 |

| 20. | Deny Journal 30 December 1918 |

| 21. | George Dangerfield - The Damnable Question p299 |

| 22. | George Dangerfield - op.cit., p303 |

| 23. | Maryan Valiulis - Portrait of a Revolutionary General Richard Mulcahy and the Founding of the Irish Free State (Irish Academic Press 1992) p27 |

| 24. | RIC Reports Inspector General May 1918 CO/904 |

| 25. | RIC Reports County Inspector February 1919 CO/904 |

| 26. | P Starrett - The ITGWU in its Political and Industrial Context (UU Coleraine 1987) p332 |

| 27. | Desmond Murphy - op.cit., p19 |

| 28. | Eamon Phoenix - op.cit., p64 |

| 29. | Eamon Phoenix - op.cit. p65 |

| 30. | RIC Reports Inspector General August 1919 CO/904 |

| 31. | RIC Reports County Inspector October 1919 CO/904 |

| 32. | RIC Reports Inspector General September 1919 CO/904 |

| 33. | Michael Farrell - Northern Ireland, the Orange State (Pluto Press 1980) p16 |

| 34. | Derry Journal May 1920 |

| 35. | Derry Journal 2 February 1920 |

| 36. | Ibid |

| 37. | Irish New 21 January 1920 |

| 38. | Derry Journal 19 April 1920 |

| 39. | Derry Journal 21 April 1920 |

| 40. | Derry Journal 19 April 1920 |

| 41. | Ibid |

| 42. | Derry Journal 17 May 1920 |

| 43. | Derry Journal 16 June 1920 |

| 44. | Derry Journal 18 June 1920 |

| 45. | Derry Journal 21 June 1920 |

| 46. | Ibid |

| 47. | Ibid |

| 48. | Derry Journal 23 June 1920 |

| 49. | Ibid |

| 50. | Ibid |

| 51. | Derry Journal 25 June 1920 |

| 52. | Ibid |

| 53. | Derry Journal 28 June 1920 |

| 54. | M Tierney - Eoin McNeil Scholar and Man of Action 1867-1945 p287 |

| 55. | Derry Journal 19 May 1995 |

| 56. | Derry Journal 28 June 1920 |

| 57. | Ibid |

| 58. | Michael Farrell - op.cit., p62 |

| 59. | Eamon Phoenix - op.cit., p251 |

| 60. | Deny Journal 14 September 1921 |

| 61. | John Bowman - De Valera and the Ulster Question (Clarendon Press Oxford 1980) p61 |

| 62. | Eamon Phoenix - The Nationalist Movement in Northern Ireland 1914-28 (Ph.D. Q.U.B. 1983) p2 |

| 63. | PRONI Cahir Healy Papers D2991 /B/2 |

| 64. | Derry Journal 9 December 1921 |

| 65. | E Phoenix op.cit.. p225. |

| 66. | F S Lyons - Ireland Since the Famine p445 |

| 67. | Irish Statesman 4 December 1926 (Letter to Editor from Cahir Healy) |

| 68. | Derry Journal 17 November 171921 |

| 69. | Irish News 19 December 1922 |

| 70. | Eamon Phoenix - op.cit.. p286 |

| 71. | Eamon Phoenix - op.cit., p281 |

| 72. | Brian Lacy - Siege City (Belfast 1980) p231 |

| 73. | Eamon Phoenix - op.cit p322 |

| 74. | Letter from Cahir Healy to the Editor of Irish Statesman 18 December 1925 (PRONI D2991/13/9) |

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||