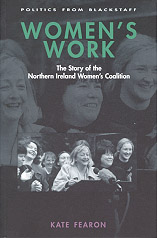

'Women's Work: The Story of the Northern Ireland Women's Coalition', by Kate Fearon[Key_Events] Key_Issues] [Conflict_Background] The following chapter has been contributed by the author, Kate Fearon, with the permission of the publishers, The Blackstaff Press. The views expressed in this chapter do not necessarily reflect the views of the members of the CAIN Project. The CAIN Project would welcome other material which meets our guidelines for contributions.  This chapter is taken from the book:

This chapter is taken from the book:

Women's Work

Orders to local bookshops or:

This publication is copyright Kate Fearon (1999) and is included on

the CAIN site by permission of Blackstaff Press and the authors. You may not edit, adapt,

or redistribute changed versions of this for other than your personal use

without express written permission. Redistribution for commercial purposes

is not permitted.

From the back cover:

The extraordinary story of the Northern Ireland Women’s Coalition is one of do-it-yourself politics. Founded in 1996 as a result of frustration with the sterility of local politics, the NIWC has a broad cross-community base, attracting women (and men) from the nationalist and unionist communities, and from both republican and loyalist traditions. In a remarkably short time the Women’s Coalition has become a respected, influential and liberalising force in Northern Irish politics, playing a key role in the talks process leading up to the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. Two of its members, Monica McWilliams and Jane Morrice, were subsequently elected to the new Northern Ireland Assembly, thanks to an energetic and highly effective door-to-door campaign. This insider account gives a unique overview of the conception, birth and first years of a unique party that coincided with, and was part of, the most far-reaching political discussions in Northern Ireland in a generation. Kate Fearon works as a political adviser to the Women’s Coalition

WOMEN'S WORK The Story of the KATE FEARON

Contents

Chapter sub-headings:

It was decided that Bronagh Hinds would coordinate NIWC representation on the Business Committee and on the Decommissioning and Confidence Building Subcommittees. Non-elected delegates could sit on all three committees, which offered an opportunity to widen participation in the talks. And in general, whenever any individual or group wished to come into the building, the N1WC arranged for visitors’ passes. It was an attempt to demystify the talks process, to open up access to the place where the decisions that would directly affect the course of so many people’s lives would take place. The NIWC also actively encouraged participation in other arenas of public life. Women generally needed prompting to apply for public positions, so advertisements for public appointments were routinely copied and distributed at NIWC meetings, and members were encouraged to apply for whatever vacancies existed. On the day the talks reconvened, Rita Restorick, the mother of the last British soldier shot in Northern Ireland - in a sniper attack in Bessbrook, south Armagh, in early 1997 - visited the talks building. She placed her son’s photograph on the NIWC’s table, spoke about his life, and how much she missed him. Meeting her moved NIWC talks delegates to tears, and strengthened their resolve to pursue an accommodation. Substantive negotiations were launched on 7 October 1997. Finally it was time for Monica McWilliams to present the NIWC’s opening position -sixteen months after it was originally due to have been given. The NIWC emphasised that the conflict was a shared problem and that in order to resolve it the talks process should be viewed as a collective, shared project. This view was not something that all participants were ready for, but it signalled the nature of the future governance of Northern Ireland, and its relations with the rest of the UK and Ireland. It repeated its view that the task of peace building should incorporate actors outside the political process: It is crucial that we identify mechanisms that will enable and encourage local communities and various interests to participate in this process of peace building, and to feel a share of responsibility for the future of this society, rather than leaving this task exclusively to the owners of this negotiating table ... [This] negotiating table is not the exclusive deliverer and sustainer of peace. We need to examine how we can bring all sectors of our society to a point where they feel that they are respected, and that they can associate themselves with the peace-building process. We believe that people cannot be expected to vote in a referendum without an understanding of how, and why, we arrived at our eventual conclusions.[7] In its opening position, the NIWC accepted the centrality of the constitutional issue, but felt the approach to its resolution would be as important as the resolution itself. The interdependency model, first described by the NIWC, was to emerge as a key theme in the eventual agreement - the interdependence in that instance being between differing political ideologies, not between formal and informally organised political structures. Of course, questions of identity, of parity of esteem, of managing difference institutionally or structurally, and of the new constitutional arrangements were on the NIWC agenda. But so were many other questions. How could decision-making structures be made closer to those they would directly affect? How could gender equity be assured through electoral systems and social support? How could the concept of participative democracy be developed to support the political system? How could human rights be guaranteed in any new framework? In relation to the latter, it was the view of the NIWC that not only were civil and political rights important, so too were social and economic rights. Justice issues also needed to be invested in if there was to be a sustainable peace. The NIWC also wanted to see confidence-building measures, but cautioned against these measures being viewed as gifts, or used as tests or obstacles in the negotiations. Confidence-building measures should be used to create a basis of mutual respect and trust, McWilliams told the assembled talks delegates. She added, ‘It would be political progress if Strand One negotiations could be driven by values and visions for the future, rather than concentrating on protecting historical certainties '[8] The negotiations got under way that day with Strand One discussions scheduled to take place between 10a.m. and 1 p.m. Strand Two deliberations would take place from 2.30 p.m. to 5.30 p.m. and Strand Three discussions from 7p.m. to 9p.m. This practice soon changed: Strand One was discussed on Mondays, Strand Two on Tuesdays and Strand Three on Wednesdays. (The Forum continued to meet on Fridays.) The format of discussion was also established. There were to be six agenda items under Strand One, and five under Strands Two and Three. The six Strand One items were: principles and requirements; constitutional issues; nature, form and extent of new arrangements; relationships with other arrangements; justice issues; and rights and safeguards. Strands Two and Three discussed all these except justice issues. An additional Cross-Strands Issues agenda was formatted, which had three snappily labelled items: principles and requirements for new arrangements to address the totality of relationships; rights and safeguards; and arrangements for validation of overall agreement. The NIWC had proposed its own agenda a year previously which was more detailed, but close to the final agreed version. (It would also tally remarkably closely with the format of the final Good Friday Agreement signed six months later.) In late autumn, the independent chairs and the governments began requesting significant papers from the delegates. For some parties, submitting papers that outlined positions under each of the agreed agenda headings was akin to pulling teeth. Papers were slow to be issued, and they were lacking in quality - amounting to perhaps no more than a few paragraphs on a page purporting to detail the nature, form and extent of new political arrangements for Northern Ireland. Bizarrely, some UUP submissions quoted verbatim from the Framework Documents published by the British government in February 1995 - a document that in the past the UUP had taken every opportunity to denigrate. When the first set of papers (on principles and requirements) for Strand One eventually reached the British government’s desk, it emerged that the NIWC was the only party to devise principles and requirements not only for the institutions and arrangements that would result from the talks process, but also for that process itself, and the actual agreement. Further, they mooted a transition period for the establishment of new structures, and made comment on what principles and requirements should guide it. The only party to recommend a time of readjustment, the NIWC in a further paper offered the view that this period should be around four to five years (effectively one term of Assembly office), and that the arrangements should be monitored during this time. At the end of the period, a report should be published on the operation of the new structures, and on their ability to manage further development and change. The talks should be about more than tackling the age-old constitutional question, the NIWC argued. One of the principles should be a willingness to transform and radicalise the democracy, to include and involve people. It should also be the duty of political leadership to manage this change and people’s fear of it - not to exploit that fear for party political ends. The agreement should be underscored by principles of inclusion, equality and human rights, and be capable of winning the allegiance of all citizens. Like the NIWC requirement for the talks process, it should broaden and deepen the democracy, drawing on the best lessons of partnership, cooperation and collaboration - people and politicians working together constructively to govern themselves. The agreement should also go beyond the narrow confines of two traditions, the NIWC stated. Specifically, it should include measures to ensure an equal outcome for women and men. Additionally, and uniquely among the parties, the NIWC suggested that any agreement should also acknowledge the hurt inflicted on all sides and the trauma existing throughout Northern Ireland, particularly among those who experienced hurt most directly and acutely, the victims. The governments still did not require a huge amount of detail. Their aim was to draw together areas of commonality in order to prioritise these and tease out the boundaries of any agreement. The NIWC, in common with other parties, laid out a baseline position. On Strand One, the NIWC submitted the notion of what they called the Northern Ireland Political Forum/Assembly, which they envisaged as comprising an elected chamber of directly elected politicians, and a civic chamber composed of business, trade union and voluntary sector interests indirectly elected through electoral colleges. The electoral system chosen for whatever chamber should deliver fifty-fifty gender-balanced representation. There should be compliance with international obligations and protection for civic, political, social and cultural rights. The two governments should have joint responsibility for citizenship and for protection of individual and collective or group rights. Issues of justice, fairness and rights had played a key role in both the causes of the conflict, and its nature, the NIWC stated. Consequently, a focus on resolving these issues had of itself potential to contribute to the resolution of the wider conflict. Arguably this was a farsighted analysis: the two big trading blocks turned out not to be unionism and nationalism, but rather the constitutional agenda and the rights agenda - each acted as a buffer to the other. Guaranteeing rights and safeguards allowed republicanism to accept what is technically, in the old language, a partitionist settlement. Ensuring the constitutional future of the Union allowed unionism to accept greater provisions on rights and safeguards. One of the NIWC’S recommendations on confidence-building measures was that, since an (undefined) bill of rights was an issue agreed on by all parties, agreement should be reached and banked on that specific issue in order to build the sense of a shared project. That would mean that some agreement could be pointed to when times got tough. But other parties were of the view that ‘nothing was agreed until everything was agreed’. Further, the MWC proposed that immediate steps should be taken to repeal the emergency legislation currently on the statute books. (Indeed the repeal of the Emergency Provisions Act and the Prevention of Terrorism Act remain lobbying concerns for the NIWC.) Noting criticisms of RUC special interrogation centres and the RUC’s powers of seven-day detention, it also called on the British government to sign up to the European Convention on Human Rights and the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights, and to conduct a wide-ranging review of the criminal justice system. Rights should not be seen as concessions to one side of the community or the other, but rather as the basis for the development of relationships characterised by equality, inclusion and respect for individual and communal rights. In a divided society like Northern Ireland, the NIWC argued, there was a need for effective recognition of a range of communal rights and the development of the concept of equality of treatment and respect for groups. The NIWC wanted to see a ‘right to active citizenship’ and the identification and development of structures and opportunities that would facilitate extended political activity and responsibility throughout local communities and civil society as a whole. The NIWC also noted the number of incidents inherited from the past that needed to be addressed by the British government and other relevant organisations - issues of alleged collusion, disputed killings and for the IRA, the families of ‘the disappeared’. A new inquiry was needed into the events of Bloody Sunday in Derry, when thirteen people were shot dead by British soldiers, and the subsequent Widgery Inquiry. The notion of the ‘right to truth’ was raised, though not a Truth Commission as mooted in an earlier MWC paper. (This marks another distinguishing characteristic of the NIWC: the ability to develop its thinking in line with the consultation that they continually conduct. Thus, too, the Civic Forum developed from being envisaged as an integral part of an elected assembly to being a separate consultative body.) Prisoners and victims were two more items on the agenda. No other party even mentioned victims in any of their initial Strand One submissions.[9] The obvious parties mentioned prisoners - the UDP, Sinn Féin and PUP. No party except the NIWC talked about the role of both. The NTWC proposed that all ‘scheduled offenders’ - who were by legal definition deemed to be politically motivated - whose organisations were on ceasefire should be considered for release. International research had demonstrated that some agreement on prisoner releases must be part of any settlement of a violent political conflict involving negotiations that include former combatants. Once the causes of the conflict had been resolved, the circumstances in which the politically motivated offences were committed would no longer exist. It was also clear to the NIWC that the feelings of victims should be taken into account in the debate surrounding early release of prisoners. It was also important that the views of all victims, and not just the victims of paramilitary organisations, should be taken into account. Victims did not speak with one voice, and this diversity would have to be factored in, making the debate even more complex. The NIWC believed, however, that it was simplistic and dehumanising to suggest that the pain of victims would be reduced in inverse proportion to the pain visited upon perpetrators. Victims, just like a society as a whole, had interests in justice and in peace building. The NIWC’s concern with reducing social exclusion was principally a concern with reintegrating those most marginalised from society by the conflict. For this reason the NIWC proposed that victims’ organisations should be resourced and supported, as should organisations supporting the reintegration of politically motivated ex-prisoners. Specific reintegration projects ought, generally, it believed, to be self-help initiatives which could be facilitated by statutory and voluntary agencies where possible and appropriate. There were wider considerations too. The NIWC proposed that any review of the criminal justice system should take into account the need to introduce strong preventative measures and sanctions against violence against women. It also advocated the adoption of an investigative as opposed to the current adversarial approach to the hearing of sexual abuse and domestic violence cases. Many of these issues made it into the final agreement reached on Good Friday, 10 April 1998, even though it appeared at times that detailed papers were being produced and going nowhere. But George Mitchell was a former judge who liked to have things on paper. So did the British and Irish civil servants. What the NIWC did not realise at the time was that many of their proposals were being banked, and would be processed, and re-presented in the name of others at future times. As had happened with the role and remit of the International Decommissioning Commission, they discovered that one party could set the agenda merely by putting in some time and producing a paper that would form the basis for discussion. The NIWC placed some of the more detailed papers before the talks. Others took the view that the deal would be done outside the negotiation room, and to an extent this was true. But everyone had to come back into the room to agree, and that was when the sheer weight of detail of the NIWC papers was brought to bear. In the discussions on North-South relations, the NIWC wanted to move away from a conflict mode that emphasised winners and losers - the so-called ‘zero sum game’. Instead they wanted to stress the importance of the parties jointly designing an outcome, or a range of possible outcomes, for the difficulties that faced them. Arguing from time-worn and predetermined positions had a limiting, if not debilitating, effect on negotiations. Some members of the talks team had been deeply struck, on reading the interim South African constitution, of the sense of a common project amongst the participants in that peace process, black, white and coloured. This was a sense that was almost completely absent from the Northern Ireland process, and the NIWC attempted to instil it at every Opportunity. The NIWC presented a list of questions it felt would help focus on some of the key issues in Strand Two:

The South African model was called upon again to introduce gender into the equality equation. Women needed to be written into the new script -the NIWC argued for equal access for women to any new structures that were produced on the island. NIWC papers spoke to the need for a commitment to collective responsibility for the outcome of negotiations and for being honest about the compromise so that there would be a shared project to put to the people of Northern Ireland and the Republic. There should be an acceptance of change in the Republic of Ireland as well as in Northern Ireland, and the agreement must strive to weave a web of relationships - North-South, East-West, and between regions on the island. North-South institutional arrangements should specifically address the need to establish common principles of civil, religious and human rights, rooted in the concepts of equality and pluralism. In its approach to constitutional issues, the NIWC placed priority on aspects that would bring benefit and progress to the people of the island of Ireland, and that promoted cooperation and interdependence among people in Ireland, and between the people of Ireland, Britain and the European Union. Both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland have small, open economies that share many common challenges, such as dealing with long-term unemployment, low levels of research and development, and heavy reliance on the agriculture sector. Whilst twice as many people are employed in manufacturing in the Republic as in Northern Ireland, both sectors are small in European terms. The NIWC thus proposed mechanisms for cooperation and cross-border decision-making to facilitate strategic economic planning on a cross-border basis. Citing the competition between the Industrial Development Agency (in the South) and the Industrial Development Board (in the North) as an example of almost anti-strategic planning, it said that they should instead work to complement each other, and not allow multinational investors to play one region of the island off against the other. Supporting them should be an all-island economic infrastructure in terms of energy, transport and research and development activity. Industrial clusters should be created straddling the border. The beneficial impact of planning for an all-island economy should include the creation of a single, high-quality labour market. Citizenship was another key theme for the NIWC, which proposed that people born in Northern Ireland should be able to opt for British, Irish or dual citizenship. If articles 2 and 3 of the Republic’s constitution were to be amended, the NIWC proposed that new legislation should guarantee those from Northern Ireland who elected to carry an Irish passport a more inclusive and active representation in Seanad Éireann - as already applied to the university sector in the Republic. The NIWC also mooted that Northern Irish people should ‘potentially have a direct vote in Irish Presidential elections’ and that district councils in Northern Ireland should possibly have the right to make nominations for the presidency on the same basis as county councils in the Republic.[10] In other words, in place of the territorial claim, the NIWC sought a more active effort by the Republic of Ireland to include those people of Northern Ireland who chose to exercise the right in a more active Irish citizenship. This reiterated the NIWC view that North-South relations cut both ways - the South had to accept change every bit as much as the North did. It also showed once again that the NIWC was not afraid to test positions out - even when it was not 100 per cent sure of them itself. The NIWC also argued that the rights attached to British citizenship should be guaranteed by the UK government for so long as the people of Northern Ireland wished to avail of them. On issues of identity, the NIWC recognised the importance of people in Northern Ireland being Irish, British, or Ulster and British, or Ulster and Irish, or whatever their preferred definition was. A purist sense of either ‘Irishness’ or ‘Britishness’ could not be taken as the essential requirement of political credibility or of acceptable political allegiance. One of the rights that the NLWC accepted was the right of people within Northern Ireland either to aspire to the reunification of the people of the island of Ireland, or to wish for Northern Ireland to remain part of the UK. It is a measure of the NIWC’s cross-community ethos that it could in consecutive paragraphs support both Sinn Féin and the UUP. Thus it supported a Sinn Féin proposal for financial and other support for ‘mutual understanding and contact between individuals ... and communities’, but taking on board the UUP’s views, it felt that this support could apply to the East-West axis as well as the North-South. The NIWC thus proposed a consultative Council of the Regions which would cover the regions of both Britain and Ireland. The NIWC’s view was that development along either axis did not exclude development along the other. The proposal found favour with the UUP, and John Taylor was keen to discuss the notion with the NIWC. The UUP proposed a Council of the Isles, which amounted to much the same thing. The NIWC was content to have its idea subsumed by others - what mattered was the fact that it was on the agenda, and being taken seriously. In its submissions the NIWC asserted its aspiration for the development of a recognised interdependence and mutuality between the people of the two islands, rather than narrow concentration on territorial claims. And as a preliminary step to establishing common benchmarks and standards for human rights north and south of the border, the NIWC advocated a coordinated North-South examination of the potential impact of the UNESCO Culture of Peace concept for the island. In essence this concept is based on encouraging values, attitudes and behaviour that reinforce nonviolence and respect for the fundamental rights and freedoms of every person. It hinges on a celebration and acceptance of people’s rights to be different and their right to a peaceful secure existence in their communities. The NTWC detailed some of the core concepts of the National Culture of Peace Programmes devised by UNESCO, such as nonviolent management of conflict, development of democratic procedures, development of sustainable, indigenous and equitable political processes. It noted also that UNESCO highlighted the centrality of women to any successful process. Indeed, it felt that any future Commissions on the Status of Women should be implemented on a North-South basis. In its response to the governments’ proposals on Strand Three, relations between the British and Irish governments, the MWC supported the proposal for a standing Intergovernmental Conference with clear lines of reporting, and put forward again the notion of a Council of the Regions. On the principle of consent, the NIWC believed that the concept must mean the achievement of the widest possible consent of the people of Northern Ireland, and not just simple majoritarianism. It accepted the guiding principle set out in the 1995 Framework Documents that ‘the consent of the governed is an essential ingredient for stability in any political agreement’. The challenge was thus to create political structures and arrangements that could command initial broad consent and which had the potential to reflect a continued broad consensus over time.

The NIWC made additional submissions to the Liaison Subcommittee on Confidence Building (LSCCB). Highlighting the positive role that exprisoners had played in the peace process, it called for ex-prisoners’ organisations such as EPIC and Tar Anall to be supported for their unique contribution in reintegrating former prisoners into their communities. A programme of prisoner release was to be linked to the eventual agreement, but the NIWC felt that there was scope for immediate action to boost confidence by increasing prisoner remission above 50 per cent and by enabling all prisoners who required a transfer closer to their families to have this facilitated as a matter of urgency - a human right that would greatly ease the suffering of the families (mainly women) involved. Barbara McCabe, who sat on the LSCCB with Annie Campbell, was increasingly frustrated with its lack of progress. It was a case of almost all the debates turning into a pile of shopping lists - ‘we want such and such’. The NIWC’s position was, not so much about unionists needing confidence building (though they did), or nationalists needing confidence building (though they did), but building confidence in the process between the public and the political participants. In the last year of the talks, it was obvious that confidence was very low in people outside, but the NIWC was defeated in repeated attempts to progress the issue. There were just shopping lists, and more shopping lists. For the NIWC representatives on the committee, prisoners were the first item on the agenda. The reason was that as the prisoners were withdrawing support for the process, the NIWC representatives felt there was a need to demonstrate that the talks participants were serious about dealing with the issue. It was additionally important for the NIWC to raise the issue precisely because it was perceived not to have a vested interest in the early release of prisoners. For Campbell it was a big responsibility particularly when the releases actually began. ‘I can remember one night waking up in a cold sweat. There had just been a huge emotional hype about the releases, and I was thinking, I’ve been part of releasing those people, and what if? So it’s a heavy responsibility, I took it very seriously.’ The NIWC representatives on the LSCCB acted as a fault line running through the committee, continually shocking those on the broad unionist side, especially as both NIWC representatives were from Protestant backgrounds. The NIWC also singled out victims’ organisations such as WAVE and An Crann as doing valuable work and being in need of resources. It called for the impact of the conflict to be highlighted, including the effects on children of having family members imprisoned or killed. Little or no provision was available in Northern Ireland for bereaved children and young adults, and with virtually no junior psychiatric beds, the NIWC noted that minors were likely to find themselves admitted to adult wards. Bereavement and counselling organisations generally were attempting to deal with the upsurge in depression and mental distress often associated with the winding down of a conflict, without additional resources. No one else was highlighting these kinds of issues in their papers. It is nevertheless remarkable how many of these concerns found their way not only into the agreement, but also into Sir Ken Bloomfield’s report on behalf of the Victims Commission - We Will Remember Them - published in 1998. Though no other party specifically mentioned victims in their written documentation, Sinn Féin, the UDP and the PUP all expressed a wish to put the matter on the agenda, but knew that this would not have been accepted by the other parties. The LSCCB was visited from time to time by Secretary of State Mo Mowlam, who would come to evaluate progress. In effect, that meant considering the various wish lists. But she was a politician used to dealing in the real world, where wish lists are never good enough. McCabe recalls a particular occasion when Mowlam came to hear views on the prisoners issue: Her reaction was to say, Well, OK, we can’t put any time scale on this but what we could do is to work on a policy which is then ready to put in place. And the others said, But we’ve already done it, here it is, we’ve done our papers. She responded by saying, These are sweeping generalisations in these papers, we have to turn this into policy. It was interesting because I suddenly looked around the room and thought, Nobody in this room has ever written a policy about anything - it has to actually be turned into some sort of practice - and now they all will be in government, it’s scary. The LSCCB was interesting, in spite of the shopping lists, and lessons learned were fed into other NIWC positions. Policing was one such issue. Ken Maginnis is the policing and security spokesperson for the UUP. There is little detailed debate about policing within the UUP, and the UUP finds it difficult to accept any criticism of the Royal Ulster Constabulary. When the NIWC representatives put the view that a lot of communities felt alienated from policing, and that paramilitary activities in those communities reflected a lack of legitimacy of the RUC in those areas, the loyalist groupings around the table supported them. McCabe suggested that one of the obvious points to make on the debate was that people in Northern Ireland have very different experiences of policing. She spoke about her own experiences of growing up in north Down, where the RUC had a relatively positive relationship with the community. She also had friends who lived in Mullaghbawn in south Armagh, whom she visited regularly. In south Armagh the term ‘policing’ is a misnomer, she said - in ten years of visiting, she had never seen a police officer. The area was, and continues to be, policed by low-flying army helicopters, with army personnel patrolling fields and roads. It was a fact of life that people like Ken Maginnis had never experienced policing like that. Neither had the loyalists, for all their alienation in urban areas. McCabe made the point that on this issue, as on all others, participants would have to realise and acknowledge others’ perspectives: just because it is not your experience doesn’t mean it isn’t the experience of others. For all his bombastic ways, Maginnis was listening. One of the loyalist representatives passed on Maginnis’s reaction to McCabe’s arguments. He had been standing beside Maginnis in the lunch queue, when Maginnis had turned around and said, ‘If that wee girl’s representative of the women of Northern Ireland, heaven help us all.’ There were moments of fun on the subcommittee. Both Campbell and McCabe got on well with Billy Mitchell of the PUP. Mitchell and Campbell both defined themselves as socialists, and one day the subcommittee was talking about poverty issues in the context of confidence building. Campbell recalls that ‘there was a clear class division emerging with the Alliance and the UUP who just didn’t know what we were going on about’. Papers had been issued and the question had been put, ‘What are we going to do about all this?’ Mitchell immediately flicked his microphone switch, lighting up the little red light at its cap. ‘Bring back Clause 4!’ Campbell lit her light in instant support. ‘Bring back Clause 4.’ (Clause 4 represented the British Labour Party’s early commitment to the public ownership of industry. The clause was dropped after a campaign led by Tony Blair.) The others didn’t know how to respond, and there was confused silence, punctured only by laughter from Campbell and Mitchell. The position papers drawn up by the NTWC and the other parties in autumn 1997 provided common papers to work from in the run-up to the talks deadline (which was originally set at 30 May 1998). On a trip to South Africa in December 1997, delegates from all parties bet on how long the actual deal would take to be done. Four days was the average wager. It would, in the end, take five days, but those five days did have to be preceded by the lengthy and expensive therapy process that was the talks process. In late 1997 and early 1998, NIWC’s key priorities had to be to insert some political will into the talks process and to boost confidence in it. Because of their absolute belief in the project and determination to make it work, members continually talked up the talks process, even when it appeared to be on its deathbed - at meetings, in pubs and clubs. No matter what size the audience, the message was: the process is going to work. We will get an agreement. It was particularly difficult to be positive in the climate of early 1998, when fear literally stalked the streets. Catholics were being murdered by loyalists simply for being Catholics - particularly Catholics who had taken personal risks and were working in Protestant areas, or in Protestant businesses. A relative of Gerry Adams was among those killed, and some loyalists also were killed during this period, friends of UDP delegates. Desirable as sharing may have been, segregation was a survival tactic. It was sheer courage of convictions that propelled many NIWC members through those hard few months.