Ulster Unionist Party (1972) 'The Future of Northern Ireland: A Commentary on the Government's Green Paper'[Key_Events] [KEY_ISSUES] [Conflict_Background] POLITICS: [Menu] [Reading] [Articles] [Government] [Political_Initiatives] [Political_Solutions] [Parties] [Elections] [Polls] [Sources] [Peace_Process]

Unionist Research Department (n.d.1972?)

Foreword General Comments Commentary on Green Paper published by the Government

(ii) Commentary on Unionist Proposals (iii) Commentary on Other Proposals

(b) N.I.L.P. (c) S.D.L.P. (d) D.U.P.

(v) Form of Government of Northern Ireland

(b) Executive Council. (c) Northern Ireland Convention (d) Northern Ire land Parliament

(vii) Supervision of Powers (viii) Northern Ireland Institutions

(b) Executive (c) Westminster Representation (d) Bill of Rights

(a) The United Kingdom interest (b) The Irish Dimension

Unionists hope that the government paper on the future of Northern Ireland is the first step in the long and arduous task of rebuilding democratic politics in Northern Ireland. It will be more difficult for some in particular than the politics of destruction of which we have had such bitter experience in the past four years. It is essential to this process that all politicians emphasise, especially in the early discussions positive aspects of policy. It is in this light that the criticisms and commendations which follow are made. We hope alL Ulstermen will appreciate the threat to peace and stabilitv posed by those who through ignorance or error fail to see that the Green Paper is only a starting point for discussion and to reject it in its entirety would be a mistake. Equally, to misrepresent it as some commentators have done as an exercise designed to achieve specific limited purposes is short sighted and dangerous. We further hope that this paper presents a concise analysis both critical and constructive which Unionists and the Ulster people can use as a basis for the hard task of convincing the British Government that the people of Northern Ireland should not merely be listened to but answered. Of course we make it very clear that to those who are in the firing line such talk of political discussion seems very irrelevant.

The people of Northern Ireland continue to face a crisis of uncertainty. Overriding their fears for the future is uncertainty about whether or not they are to be permitted an effective say in their own destiny.

Insofar as the green paper takes note of what some of their representatives has e said it is welcome.

However, what matters now, as the green paper itself recognises in paragraph (d) of section 79, is the need to achieve the widest possible consensus for any proposals. That consensus cannot be achieved by discussion. It can only be achieved by understanding the popular will in the Province and by persuading people that the final proposals pose no threat to either the stability of Government or the Union.

A major object in publishing this Blue Paper has been to remove doubts and fears caused by the misinterpretation of the Government Green Paper by some commentators and political groupings. This paper serves to define and explain what Unionist attitudes are to the current debate on the future of Northern Ireland.

General comments 1. The family that has lost a son, husband or relative, the farmer who has had to face a terrorist single handed the shopkeeper who has seen his business blown to smithereens, are unlikely to see any relevance in future political structures at this point in time. The number of people who would hold this view in both communities is now very large indeed. They will he very surprised to find their most urgent concern confined to subsection (h) of the last paragraph but four of the discussion paper where it says:

"It is of great importance that future arrangements for security and public order in Northern Ireland must command public confidence, both in Northern Ireland itself and in the United Kingdom as a whole". There is room for a paper dealing exclusively with the Governments ideas on security for the province including a lengthy section on the "Irish Dimension" - on what it would be reasonable to expect the Republic to do to assist with holding violence in check. Some of the chapter headings in this section on the Irish Dimensions would be:-

Border security 2. The green paper is greatly concerned with administrative structures and deals surprisingly little with political roles. If there has been any failure in the past fifty years it has been a failure of politicians not structures. The tradition of boycott and abstentionism on the one side has helped to develop and maintain an uncompromising rigidity on the other. The Unionist Government at Stormont tried to promote discussion of improvements of political roles in the Province with singularly little response from the opposition. The green paper Lids to point out that the thin Line process it tries to promote will he worth less without some constructive political response from all parties. 3. Certain politicians and the media have made great play with the green papers three paragraphs (out of 83) on the Irish Dimension. If the Irish Dimension means that Ulster and the Republic happen to share common sea and land boundaries, then it is relevant particularly in the E.E.C. context. If it means that Ulster and the Republic have common interest in containing violence and promoting peace and stability then it is relevant. If however it means that there is any question of a change in the culture, traditions and citizenship of Ulster so that Ulstermen are no longer free to develop an open. Secular, non Gaelic society then it must he recognised that such changes will be resisted absolutely . If it is right to talk about an Irish dimension in UIster, it is also right to talk about a British dimension; just as it is right to talk about a British dimension in Wales, in Scotland, in the Isle of Man, and in the Channel Islands.

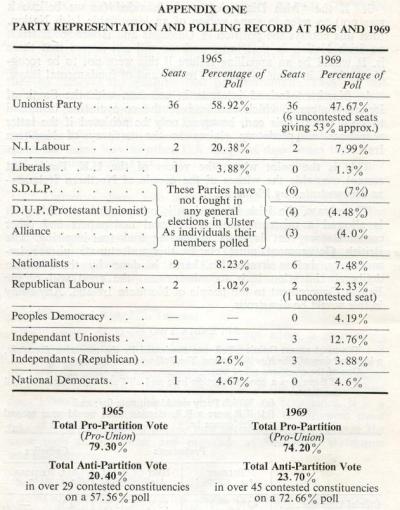

4. The green paper uses as its base the proposals of various political groups. With the exception of the Unionist Party and the Northern Ireland Labour Party, none of the other groups passed the test of winning seats at the last Northern Ireland election.1 Both the Alliance and S.D.L.P. were formed since 1969. The Liberals and N.U.M. though in existence in 1969 did not win seats. It is a matter for regret that the Democratic Unionists failed to produce a document in time for inclusion and that the Nationalists have still failed to produce a document of any kind. It is also a matter for regret that the S.D.L.P. Nationalists and D.U.P. boycotted the Darlington conference. 1 See Appendix One. It is now high time the people of Ulster had a proper opportunity to indicate their wishes through the ballot box at a general election. Without better information about the strength of popular support for the various political options it will be impossible for the U.K. Government to frame its White Paper in such a way as to achieve its avowed objective - the widest possible consensus. 5. Sovereignty and citizenship are at stake in Ulster. These are matters over which no compromise is possible. The U.K. Government must therefore recognise that any future political structures are likely to involve Government without consensus. The question is not whether the 1949 Pledge on the constitution is affirmed but whether a system of Government is set up which gives unreasonable advantage to those who would use any means to undermine the citizenship of their fellow countrymen. 6. There is one respect in which the green paper can be welcomed wholeheartedly. Insofar as it begins the process of making clear to all concerned the constitution under which Ulster will be governed for the foreseeable future it begins clipping the wings of those who would forego no stratagem in seeing that no firm decisions for the future are made except in a United Ireland context. From a Unionists point of view the sooner it is made clear that the wish of the majority will be respected, the better. A White Paper in June, 1972 would have been better than a Green Paper in October, 1972. The sooner a final White Paper follows which weakens the support of those espousing extreme causes the better. So long as uncertainty persists there is a danger that violence will shelter any attempt to build structures for the province. Such destruction is certainly the aim of the I.R.A. 7. The key section of the paper is Part IV. "The Way Forward". which lists the cretence on which firm proposals will be based. Unionists are encouraged to read

PART 1 - COMMENTARY ON THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 1. It is administratively tidy but politically unfortunate that a historical background had to be included in the paper. There is a danger that in discussion and debate too much attention will be focussed on the past and too little on the future. Part I apportions praise and blame to all groups but it will be all too easy to abstract only three points which favour ones own view. 2. Four points stand out in the 25 paragraphs.

(a) Paragraph 9 does not give a balanced history of the Special Powers legislation which was largely if not exclusively inherited from U.K. Acts for Ireland.(i) Moreover the Ulster Special constabularies were recruited by the U.K. Government (not the N.I. Government) during the period when total responsibility for security remained at Westminster, i.e., until 1923. This fact is glossed over. [Note:] (i) A variety of similar legislation including Emergency Powers (Defence) Act 1939 has been in force in Great Britain which allowed provision be made for the "apprehension, trial and punishment of persons offending against the Regulations and for the detention of persons whose detention appears to be expedient (to the official specified in the Regulation) in the interests of the Public Safety or the defence of the realm" S.2(a). (b) The value of Stormont as an escape valve for political tension is nowhere recorded. Without the local Parliament there could well have been many more outbursts of street politics than there in fact were. The absence of any analysis of Stormonts contribution in this respect suggests that the writers were not fully alive to the political aspect of events. (c) There is throughout a lack of analysis of the underlying nature of the Northern Ireland problem. The historical summary in Part I describes symptoms not causes. This concentration on an administrative analysis is a considerable weakness of the Paper. Without a deeper examination of the social, cultural and ethnic forces at work, an abbreviated historical summary is of little value. In this case it has meant that the more fundamental causes of strife have not been examined. There are, however, several perceptive analyses of particular aspects of devolution in Northern Ireland. 1. The lack of a real budget and of any meaningful control over revenue limited the scope of legislative activity. In many arenas Northern Ireland could have used her developed powers to diverge from British legislative practice. This was not done, however, for two reasons. The dependence on a budget determined at Westminster (and the need for financial subventions) was only one reason. There was no real desire to diverge from British practice and, if there was, it was only achieved after very close consultation. This was due in no small measure to the desire of the people of Northern Ireland to remain as close as possible to their neighbours in Great Britain. 2. Devolution has however had considerable advantages. The description (in the Green Paper - para 6) of legislation unique to Northern Ireland does not fully cover these. The people of Northern Ireland had for fifty years a close, personal and responsive form of Government that could never have been provided from London. Their Ministry of Commerce probably typified this. An industrialist was never more than a telephone call away from the decision-maker. Good industrial relations were greatly helped by the availability of a locally controlled reconciliation procedure. Consequently Northern Ireland has the best record in the British Isles of industrial harmony. 3. It Was this combination of a devolved government and legislature that achieved the advances mentioned in the Green Paper (para 15). The progress made in standards of education and health was all the more remarkable when one considers that this was achieved against a backcloth of abstention and uncertainty. It is however a pity that the Green Paper instead of describing the fact of abstention and boycott, did not seek to find the reasons for it (or, indeed, for the mutual allegations or discrimination made by both sides). 4. The description of events from 1969 to 1972 is too abbreviated. Consequently it is tempting to be drawn into argument about the past. This we have resolutely sought to avoid, even though we have strong feelings about a campaign that started as, ostensibly, a campaign for civil rights and ended as a campaign of urban guerrilla warfare.

PART II - COMMENTARY ON THE UNIONIST PROPOSALS The Unionist Party. 1. It is worth pointing out that these proposals were by no means conceived as a final rigid political framework. Indeed at the Darlington conference a number of further ideas were developed. For example the five Parliamentary Committees are conceived as "five and four" committees - five representatives of the majority party and four of minority parties - so that the work of the committees must be done more or less by consensus and not by instruction of the party whip. 2. Our intention was not that the function of the committees should merely be to "cover the activities of a department". Our Committee proposals go much further than this. Apart from scrutiny they will have a role to play in policy formulation and in legislating. 3. They would have power to sponsor their own legislation. There would be no distinction (as at Westminster) between a Government and a Private Members Bill. The distinction would be between a Government and a Committee Bill. 4. All Bills on their introduction would be referred to the appropriate Committee. The Committee would conduct hearings in which officials and Ministers would have to defend their measures before the Committee. Committee sponsored Bills would be referred to the Government Department for comment and criticism. 5. The Committee could delay a Bill by refusing to report it to the House. This would be the method of rejection. While the House would still have the power to order the Bill to be reported, we envisage this power as being circumscribed and rarely used. The number of expert staff, the research facilities, the bill drafting facilities that would be available to the Committees would give them considerable strength and esprit de corps. 6. It was in these conditions that Unionists hoped a non-partisan approach would develop even on the most controversial issues. The value of this diffusion of legislative power to committees would be seen in the increasing frequency of unanimous Committee recommendations, the considerable cross-voting and the blurring of party lines that would take place. In these circumstances a more general support would be needed for policies and legislation than formerly. (Though there might have to be realised a means of referring deadlocks to the people of Northern Ireland). 7. It is noteworthy that only the Unionist Partys proposals use the old Parliamentary nomenclature. This terminology is not, as some have said, a matter of personal dignity and status. 8. First, the status of a local Parliament matters enormously to the people it serves and is a factor in its effectiveness in handling political problems. A change in status for the Stormont Parliament could well lead to its being by-passed on every occasion so that political disputes would always end in London as a matter of course. Second the calibre of public representatives in the Northern Ireland Chamber would be likely to suffer. Third in the E.E.C context it will become more important that the local institution in Ulster have standing. The Republic will have 10 MPs at Strasbourg and I Commission at Brussels. In order to ensure that Northern Ireland interests are properly weighed in the U.K. and in Brussels a strong local administration will be needed. 9. Secondly, names are important, but credibility is crucial. It is only an institution that has real influence and more financial scope that can fairly and effectively manage controversial issues. We believed that could only he expressed in a devolved Parliament and a Regional Government. The greatest danger we see in a more diminutive assembly is its tendency to parochialism. If that assembly is to play the role envisaged for it in a Council of Ireland, in the E.E.C. and in acting as the focus for the views and problems of the Province, it must be a body of weight that will attract men of ability.

PART III - COMMENTARY ON THE OTHER PROPOSALS A few comments are needed on the proposals put forward by other political groups. Our criteria of judgment remain those given in the Unionist document; the safeguarding of the union and the creation of structures which would permit all reasonable people to play their part in public life. (a) Alliance Party 1. Like the N.I.L.P. and other groups the Alliance suggest S.T.V. proportional representation for the regional assembly. The many arguments for and against P.R. have been fully rehearsed in recent months and Unionists have kept a very open mind on the issues involved. The Political groupings in the Province are already so fragmented and range so wide that a voting system which encourages this further is unlikely to produce a more stable administration. 2. As far as security is concerned the suggested division of responsibility seems hardly satisfactory. Security is very much a matter for the men on the spot and the most important aspect of their work is that of intelligence. Local people will always constitute the security forces so it is vital that representatives of the local community are fully involved in the policy making process. Otherwise one cannot expect the public to have confidence in the security forces and join them. 3. On the question of security it is also worth saying that never again should the U.K. Government and public be permitted to become so ignorant of the nature of the security problems faced by the province as they were in the 1950s and early 1960s. 4. The Alliance proposal that the Executive of a Northern Ireland Assembly should be a Committee of chairmen of Committees themselves elected by proportional representation is almost certainly unworkable. Quite apart from the impracticability of executive management being performed by committee, the P.R. principle would almost certainly create a situation in which it would be all too easy for a determined politician to undermine and wreck the operation of the whole system by judicious use of publicity and intransigence.

5. Their proposal at the Darlington Conference (that the chair of the first Committee should go to the largest Party, that of the second to the next largest and so on until the first party had four chairs, the second, two and the third, one) is an example of just how artificial and contrived the methods of obtaining "community" government can be. Such a system would be the hostage whose aim is to block and to wreck. (b) N.I.L.P. 1. The points noted above e in relation to proportional representation and committee management apply equally to these proposals, though the N.I.L.P. recognise the impracticability of forming parties into contrived coalitions. 2. The N.I.L.P. proposal that Committees elect their own chairman would, admittedly, produce a majority executive. It is doubtful, however, whether it would be a cohesive one capable of acting as the necessary co-ordinating mechanism that an executive must provide. Predictably an undignified scramble for positions on committee would result in a very motley executive (unless the Party caucus had predetermined the votes, not an uncommon happening in many town it halls). 3. The suggestion that local susceptibilities on such subjects as divorce, abortion and homosexual practices be disregarded does not appeal to Unionists. Further if any blocking mechanism from Westminster is required (and Unionists doubt that it is) Unionists feel it should be one to which in some way the responsibility for resolving conflict is referred hack to the people of Northern Ireland. (c) S.D.L.P. 1. These proposals although well constructed and arranged, appear r to he based on a total unrealistic basis and fail to take any account of the aspirations of the vast majority of Ulster citizens 2. It is not in the interests of the majority in Ulster for Ireland to become united under any conditions that can be foreseen at the present time. The disadvantages, cultural, educational, economic, social and political are well set out in the N.U.M. pamphlet, Two Irelands or One. 3. Any kind of "interim" system of government would be totally unworkable because constitutional uncertainty would he perpetuated and provide a breeding 2round for violence as we know from present experience. 4. The size and method of electing the executives is guaranteed to produce a worthwhile stalemate. The denial of representation at Westminster is a flagrantly undemocratic proposal especially when coupled with the proposal for a new reformed South of Ireland, clearly to which no Unionist could possibly make any contribution if the purpose was to place integration of Northern Ireland in a sectarian Republic.

5. The "immediate declaration" required of the United Kingdom that it would positively encourage unity epitomises the attitude of the S.D.L.P. which has been, for so long, to ignore the aspirations and feelings of the majority community Such a declaration would be such bitter gall to Unionists that one is driven to ask whether the S.D.L.P. intended this as an interim scheme for unity or an interim scheme for disaster. (d) Democratic Unionist Party The proposals of the Democratic Unionist Party have been published since the writing of the Green Paper. They envisage an increase in Ulster representatives at Westminster, a Northern Ireland Grand Committee at Westminster and a Greater Ulster Council to administer the upper tier of local government powers through committees. They would make Government so remote and they include yet again all the weaknesses of a committee run local executive.

PART IV - COMMENTING ON SOVEREIGNTY AND CITIZENSHIP 1. The reiteration - without equivocation - of the statutory and verbal pledges about the constitutional and territorial integrity of Northern Ireland are very welcome to Unionists both those inside and outside the Unionist Party. 2. There can be no doubt that, as the Green Paper says, adherence to these pledges would be inconsistent with any attempted transfer of sovereignty or any attempted condominium over Northern Ireland. Not only would such an attempt drive the majority of Protestants to resistance but it would, in all probability, be unacceptable to a majority of Roman Catholics (see Appendix I) in Northern Ireland. 3. The Plebiscite is welcome. Ironically it is not something that Unionists would have welcomed 12 months ago. It is a measure of this fear and uncertainty that in the supervising period they are not disposed to take promises at face value or pledges for granted. Hopefully, the Plebiscite should remove these doubts and fears. Equally it is to be hoped that there will be such a decisive yes to the Union that demands for tinkering with the Constitutional integrity of Northern Ireland will lose their appeal. 4. Unionists find it disturbing that the Green Paper refers to a "neutral" declaration having been made (paragraph 2b) by the British Government on the position of Northern Ireland. They do not seek to read too much into the words and phrases used but in this particular phrase is summed up the kind of alien disinterest that worries an d alarms the Ulster public. It should be made clear that not only is this needless but that in Ulster, where confidence is crucial, such a reference is positively harmful. One need only point out the incongruency of this term being applied to Scotland to show how Ulster people feel about neutral declarations. We accept this as showing no ulterior motive but as rather being representative of a distance gap between the Government and the feelings of the Ulster public. 5. The suggested machinery that could perhaps provide a potential and consentual means to achieve unity (paragraph 42(c)) is obscure. Unanswered questions include how, when and at whose instigation could this take place? 6. Legislating for fundamental constitutional change (Para 42 (d)) is, of course, entirely at conflict with the absolute commitment given elsewhere in the Paper concerning the integrity of Northern Ireland. There can be no compromise on this - a fact that is expressly recognised. 7. The implications of a system of joint consultative machinery in Ireland were not lost on Unionists when they proposed such a system in "Towards the Future." To us, however, essential prerequisites to any co-operation remain:

9. This is also a powerful reason in favour of the maintenance of a worthwhile devolution. The Northern Ireland Assembly must be of a stature that permits it to pins this role equally and effectively on behalf of the citizens of Northern Ireland.

PART V - FORM OF GOVERNMENT OF NORTHERN IRELAND WITHIN THE UNITED KINGDOM 1. Unionists welcome the recognition explicit in the Green Paper (Para. 43) that NO question of Irish Unity can arise until the people of Northern Ireland express such a wish by plebiscite, and that the immediate is how Northern Ireland should be governed inside the United Kingdom. They have always accepted the consequent rights and responsibilities (in War and Peace) consequent to their desire to remain with Great Britain. 2. They would not, however, accept that this gives any transient administration at Westminster the right to present arbitrary ultimata. We do not believe there is any suggestion in the Green Paper of an "either you take what we give you or leave" attitude. Westminster well knows that representative democracy means Government must listen to the views of all its people (Indeed a significant part of the Green Paper rests on that premise). (a) Total Integration 1. This is akin to integration "on the Scottish Model", a system that was at one time advocated by the D.U.P. In exchange for the loss of a local executive and legislature we would obtain approximately 20 votes at Westminster and an Ulster Grand Committee to scrutinise Northern Ireland legislation. 2. The Green Paper rightly says this would be the reversal of the tradition of a half century. It would also mean the loss of the vote in considerable benefits of devolution and of a personal and highly responsive system of government. Not mentioned but of supreme importance is also the role of a local parliament in providing a community safety valve which politicians can ventilate grievances (e.g. on security, discriminating practices, etc.) adequately on the floor of a local forum. 3. Unionists question whether any significant proportion of the population would resist integration. They merely regard it as a very second-rate alternative to a system of real devolution. They would be adamant in asserting that the wishes of Southern Ireland should not be relevant on this matter. There are, of course, already strong, convincing and unanswerable arguments that there should he an increase in the number of Ulster M.P.s at Westminster. Our membership of the E.E.C. with the consequence of removing a large amount of policy making on Regional Policy and Agriculture to Brussels is in itself sufficient to ensure this is so. (b) A Purely Executive Authority (a Northern Ireland Council) 1.This second model is, in essence, that of integration on the Greater London Council model. In exchange for the loss of a Regional legislative Northern Ireland would obtain increased representation at Westminster, a Regional Executive and a Secretary of State. While the Regional Executive would retain some of the assets of the Stormont system - speed, closeness to the people, responsive to popular opinion, etc. - it would lose many of the potential benefits of devolution - legislative innovation, control over financial powers and incentives, etc. 2. This somewhat colourless regional executive would, however, fit in with the Macrory scheme for local government. While the Green Paper talks of the reversal of the traditions of 50 years with reference to integration, it should also be remembered that this is equally true of a weak, watery form of council or assembly. (c) The Northern Ireland Convention This would not have executive powers but would act as an integral part of the Westminster process in relation to local legislation. In essence it is an advisory and non-executory body. It would seem to give none of the advantages of the Council while retaining all the disadvantages. (d) A Northern Ireland Parliament or Assembly Unionists regard this as the first and most preferable option for Northern Ireland. It puts together the twin alternatives of a Regional assembly and of a devolved Parliament. Unionists believe that to produce a viable structure that can play its part in the shaping of the future of Northern Ireland this assembly or Parliament must be credible. It would be disastrous for the Province to have a weak, half-was house unable to exert real influence over the interests of the community it serves - neither complete integration nor real devolution.

PART VI - DIVISION OF POWERS BETWEEN UNITED KINGDOM AND NORTHERN IRELAND INSTITUTIONS 1. Unionists accept the rationale of powers contained in Paragraph 47 a-d, in so far as it covers local services, social value legislation and measures designed to meet local conditions. The latter sphere has, in particular, seen remarkable local progress. In Commerce, industrial development, industrial training and in tourism distinctive contributions have been made by Stormont. It was in large measure due to the existence of Stormont that the Housing Trust, the Housing Executive and other bodies tailored to suit local needs developed. Harland and Wolff and Short Brothers obtained special assistance not just because of their problems but because of the influence exerted on their behalf by a local administration. 2. There is one highly relevent gap in this analysis of powers - what might he described as the argument from the EEC. Which proceeds from the contention, already mentioned, that U.K. membership of the Common Market will necessitate finding some means to ensure adequate representation of the Provinces interests. There are three channels for this the Ulster Representation at Westminster, the role of the local Parliament and the co-operation that may be achieved in the joint Irish Council. The importance of the local assembly is crucial in all these matters. 3. Unionists, however, go further. We do not accept the categorisation in Paragraph 48. Powers over electoral law and boundaries, the courts and administration of Justice, security and public order, and the police are not necessarily divisive. They may be controversial but they are really no more divisive than the very existence of Government itself. 4. We believe this because it is not the powers themselves that are "divisive" but the existence of the identifiable unit of Northern Ireland linked to the United Kingdom. The fact that citizenship is so protected has always been divisive. It is divisive because of a refusal by a small minority to accept that citizenship. This is why the very existence of Government has been made to seem divisive and this is why, because it does not examine the fundamental nature of the struggle, the Green Paper appears to us to miss the real issues on policing. Indeed this is also why Direct Rule has proved every bit as "divisive" as Stormont Rule. No local executive can responsibility administer Northern Ireland unless it has authority over internal security, i.e. police, law and order. 5. The question of finance is crucial. Here Unionists are pleased that the need is recognised for the achievement of greater autonomy within defined powers. They do not (and never did) expect control over money that comes direct from Westminster, they do expect more power over money that is directly attributable to local taxation. The lack of this greater scope was a weakness of the old system that is adequately pointed out in the Green Paper.

Part VII - SUPERVISION OF POWERS. 1. Unionists regard this section as crucial. It was partly the reason why they devoted so much emphasis to the introduction of a Bill of Rights and the restricting of emergency powers. They realise that not only the provision of a real and effective role for all is important but so too is the provision of checks and balances to ensure the system is patently fair, open and representative. 2. There are a wide range of possibilities, many of which are detailed in the Green Paper (paras 50 and 56) - the Royal Assent, Section 75, Parliamentary Supervision at Westminster, and local supervision by specially tailored institutions. There is also, as is mentioned, the possibility of introducing popular initiatives, i.e., the referal of legislation by request to the people of Northern Ireland in a Referendum. While entrenched majorities are not, in our opinion, helpful, all these procedures require to be carefully examined to ensure that they would melt the Unionists from unalterable criteria.

PART VIII - NORTHERN IRELAND INSTITUTIONS The Form of the Assembly / Parliament 1. The Unionist attitude to the mini "Parliament" has already been mentioned. 2. While Unionists recognise the validity of the arrangements (Para 52) about the worth and role of an Upper Chamber, they are firmly convinced that no useful purpose is served by retaining an Upper House whose members are a microcosm of the Lower. It is, however, perfectly possible to give the Upper House a different structure and a worthwhile role. 3. Throughout the Green Paper it was noticeable that the Government was anxious to keep its options open on those areas of innovation which might particularly affect constitutional practice in the rest of the United Kingdom. This was particularly so in relation to Proportional Representation elections and to the introduction of a Bill of Rights. Unionists are not convinced that the S.T.V. method of election will make any substantial or desirable difference to the composition of a Northern Ireland Parliament. They do, however, remain open to argument. We discuss the crucial importance of a Bill of Rights later in this paper. Earlier in this paper the role of the Unionist Committees was discussed. It is the belief of Unionists that this system can present a real and worthwhile role for all to play. We believe they will permit a considerable diffusion of power, without attaching the stigma of executive responsibility to those who do not want it or to those who do not gain sufficient votes to obtain it. It should be made clear that in the last analysis an effective voice and real influence and not won In constitutional means but by the character skill and hard work of Political Representatives.

2. The Executive 1. Unionists could not agree more with the perceptive analysis contained in the Green Paper about the difficulty of producing an artificial sharing of power that is not open to deadlock and frustration. They also believe that, while government should be as fully representative as possible, it should also be democratic. Political change should be effected through party political structures not through complex and contrived constitutional mechanisms. The latter, if it were sought to achieve it by constructing an artificial executive, would he unacceptable to the vast majority of people in the Province. 2. Such a system would not just stultify opposition. perpetuate divisions permanently, but would he prey to negative politics. As is made very clear in paragraph 61 a new type of minority representative would be needed to allow such a system to work. Some may say lack of power has made minority politicians irresponsible. Unionists however take the view that the reasons for negative minority politics have, up to the present, been rooted in the fundamental clash of national identities in Northern Ireland. In the future this is likely to be increasingly less valid. We would hope that this will be demonstrated in any forthcoming elections. 3. As at the present, however, it is difficult to see any system of enforced community government (even with clear dispute resolution procedures) working effectively or being acceptable to more than a limited minority. An executive must, We believe, be a willing partnership of those who agree sufficiently to provide a cohesive direction for policy. (3) Representation of Northern Ireland at Westminster The point has already been made that Northern Ireland is underrepresented and that any settlement should seek to correct this. It is also important to ensure that the remoteness - gap between Westminster and Northern Ireland is bridged. Added to this is the need to ensure proper representation of Northern Ireland interests in the Common Market. (4) A Bill of Rights Considerable benefit - in the control of legislative and executive activity - can he achieved In a practical, precise and comprehensive Bill of Rights. "Towards the Future" made it clear that these Rights should be more than mere yard sticks for Governmental behaviour but should have an immediate and direct influence on the sphere of Governmental activity . They should be policed by a Court skilled in Constitutional practice and by a process that is easily accessible and speedily effective.

PART IX - COMMENTARY ON GREEN PAPER SECTION "The Basic Facts" 1. Unionists have always been appreciative of their position in the United Kingdom - they have indeed on several occasions died to preserve the qualities that position entails. They did not do this out of financial motivation but because of a much more complex patriotism and cultural identity. While grateful to the generosity of the rest of the Kingdom they regard the subsidies and loans (Para 67) as a consequence of common citizenship much the same way as other U.K. Regions draw from the centre and from the South Fast. This is recognised by the Green Paper (para 70). 2.Unionists share with the authors of the Green Paper the belief that number one is interdependent with the rest of the U.K. (Indeed they believe that Southern Ireland should also recognise its somewhat similar position). Thoughts of "going it alone" have no place in the affections of Unionists - with the proviso that if their citizenship in the U.K. was to be threatened against their wishes (as a majority) then such a course would be a real option. (a) The United Kingdom Interest The people of Northern Ireland do not adopt a patronising attitude to the rest of the United Kingdom. They appreciate a common and true bond of friendship and identity and welcome the fact that this was recognised in the Green Paper. The relationship between Northern Ireland and the rest of the United Kingdom does indeed involve rights and obligations on both sides. It is a basic tenet of representative democracy that Government must take the views of all its people into account. Ulstermen have the same right to pressurise and persuade as Scotsmen, Welshmen and Englishmen. (b) The Irish Dimension 1. This section has created more speculation (unfortunately, rather predictably) than any other pan of the Green Paper. 2.The Unionist attitude is precise and categorical. If these actions, as we believe they do, mean a recognition of the fact that both parts of Ireland have a duty to end terrorism, if they mean that both parts of Ireland have mutual problems which require mutual co-operation (and recognition) then that is acceptable to Unionists. The South can expect no co-operation and no influence unless it shows itself more reads than it has been in the past to adopt a friendly and co-operative attitude with both Northern Ireland and the U.K. as a whole. 3. If the "Irish Dimension" was intended ( we believe it was not) to refer to some notion of an identifiable Irish Nation, then this betrays the position of Unionists and is wrong. There is no Irish Nation in that sense and we will not accept that there is. It would be an appalling failure if this were not to be recognised - both in terms of political reality and of fundamental issues. 4. Northern Ireland interests in common with the South of Ireland - interests which can lead to the co-operation beneficial to both parts. This can, however, only he achieved if the latter renounces all predatory claims to the territory of Northern Ireland. This is the point where the voices of the U.K. Parliament cannot override the wishes of the people of Northern Ireland - as demonstrated by Plebiscite. The phrase, the Irish Dimension, is opaque and misleading. It is allowed a misrepresentation by local newspapers and other commentators that is both misleading and fear-inspiring. The British Government must clarify this unfortunate phrase immediately, before irreparable harm is done by those whose deliberate intention it is to misrepresent the good will of the British Government to the people of Northern Ireland. Any delay in this would he disastrous.

The most recent Opinion Poll was conducted by the magazine Fortnight, a local version of The New Statesman. The Poll was held in July 1972. One of the questions asked was:

If there was a general election here and all Parties you know of had candidates

PARTY REPRESENTATION AND POLLING RECORD AT 1965 AND 1969

See also: Northern Ireland Office. (1972) The future of Northern Ireland: a paper for discussion, (Green Paper; 1972). London: HMSO.

|

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||