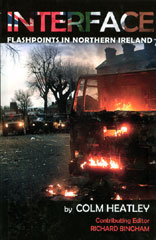

Interface, Flashpoints in Northern Ireland, by Colm Heatley[Key_Events] [KEY_ISSUES] [Conflict_Background] INTERFACE AREAS: The following chapter has been contributed by the author Colm Heatley with the permission of the contributing editor Richard Bingham and the publishers Lagan Books. The views expressed in this chapter do not necessarily reflect the views of the members of the CAIN Project. The CAIN Project would welcome other material which meets our guidelines for contributions. This chapter is from the book:

This chapter is copyright Colm Heatley (2004) and is included on the CAIN site by permission of Lagan Books and the author. You may not edit, adapt, or redistribute changed versions of this for other than your personal use without the express written permission of Lagan Books. Redistribution for commercial purposes is not permitted.

by

Contributing Editor

Conclusion Chapter

Project Editors

About the Author Colm Heatley is a freelance journalist who has written for The North Belfast News and other organisations. A native of Belfast, Colm has an intimate knowledge of several Interface areas and his experience as a reporter of such events for The North Belfast News gives him a unique understanding of the events covered in this book. CoIm is currently in South-East Asia, researching his next writing project.

Editorial Team Contributing Editor and author of this book's last chapter, Richard Bingham, has been a keen observer of current affairs for many years. Richard is also from Belfast and has many contacts with grassroots community workers and politicians.

Contents

Introduction

Alliance Avenue, in north Belfast, is undoubtedly one of the most infamous and bloodiest streets in Northern Ireland, Throughout 30 years of the Troubles almost 20 people have been killed there by loyalists, the IRA and the British Army. A narrow street of just over 100 houses it is the dividing line between the republican Ardoyne estate and the small loyalist enclave of Glenbryn. In a troubled society the street exemplifies the divisions that mark out Belfast from other European dues. Now exclusively Catholic it was, until the Troubles began, a mixed street. In 1971 the British Army had erected a makeshift peace line to separate Alliance Avenue from Glenbryn. By the late 1980's the peace line stood 40 foot high and was a permanent feature of life for residents on both sides, with dialogue between the Catholics and Protestants who live within touching distance of the peace line virtually non-existent. It is the dividing line, the frontier, between Protestant and Catholic Ardoyne. Catholic Ardoyne is now almost entirely fenced in by peace lines. Apart from the partition at Alliance Avenue, a wall some 300 yards long, constructed by the Northern Ireland Office (NlO), blocks off Ardoyne from the Crumlin Road. In the early 1980's Ardoyne houses on the fringe of the Crumlin Road were knocked down, as were homes and shops on the Protestant side. None were ever rebuilt, creating a wasteland. To the untrained eye the wall looks unremarkable, almost as though if should be there, but it was created with the sole intention of separating Catholic and Protestant. One aspect of peace lines in Belfast is the form and shape they are given. The wall on the Crumlin Road has been beautified with ornate carvings and plants to make it look somehow natural. However, people from Ardoyne resent both the wall and the buffer zone, which started to grow. In effect the area is encircled by security walls of one sort or another. And, of course, Protestants on their side of the peace line similarly resent this obstacle to normal activity. Mutual distrust, suspicions and sectarian tensions characterize the two communities' relationship and these tensions burst onto the surface dramatically in June 2001 in the form of the Holy Cross protest. Scenes of frightened Catholic schoolgirls running a gauntlet of abuse from loyalist protesters as they walked past the Glenbryn estate to get to their school captured world headlines. In a protest marked out, even by the North's standards, for its bigotry and viciousness, few could comprehend the scenes on the TV screens. Protestants from Glenbryn insisted the schoolgirls would not be able to walk past their estate to get to school because, they claimed, the IRA was gathering intelligence in this way. The Catholic parents were equally adamant that their girls should be allowed to get to school in the quickest way possible, comparing the protesters to the white supremacists of 1950's Alabama. While an alternative route was available, many Catholic parents refused to use it, asking why should they have to use the back door', which to them symbolised second-class citizenship. To many Protestants however, such reasoning was unconvincing. Fraser Agnew, Independent Unionist MLA for North Belfast points out that in many instances, Unionists have had to employ practical measures to avoid conflict.

"For years, when using our Orange hall in what is now a Catholic area, we had to use the back door to avoid confrontation with local residents. And we didn't complain, it was just what we had to do." Despite the best efforts of mediators, politicians and churchmen, the Holy Cross protest lasted for the best part of a year before it was resolved. Protestants claim the protest began when two loyalists puffing up paramilitary flags at the Ardoyne Road were attacked by Catholics. They said a car rammed the two men and both narrowly escaped injury. People from Ardoyne have always strenuously denied the claim, saying no such incident took place. They accuse Protestants of seeking an excuse for the violence that followed. In the 12 months after the protest ended Alliance Avenue was the scene of near nightly rioting between Protestants and Catholics. The PSNI (The Police Service of Northern Ireland, the name of the reformed Royal Ulster Constabulary, the RUC) were called to deal with scores of bomb attacks on Catholic homes, and more than a dozen families applied to move out of the street because of sectarian intimidation. Sixteen Catholic families, some who had lived there since the early 1980's, applied for government grants to move out because their lives were in direct danger. Protestants on the other hand equally claimed vulnerability because of attacks on their homes. The Holy Cross protest was, however, the latest stage in a thirty year conflict of daily grinding battles between the communities living along the Alliance Avenue and Glenbryn peace line. The Holy Cross protests heightened sectarian tensions across the North in a way not seen since the Drumcree stand-off in 1996. For more than six months loyalists blocked the road to the Holy Cross Girls' Primary School. By a quirk of history the Catholic girls' school, which draws most of its students from Ardoyne, sits opposite the loyalists Glenbryn estate. To get to the school parents and children have to walk past the housing estate, but there was never any loyalist protests outside it even during the worst of the Troubles. But now scores of PSNI officers lined the road to allow the parents and children access to the school, as hundreds of loyalists protesters jeered and threw stones while the children walked by. On 1 September 2001, the protest took a further violent twist when a loyalist threw a pipe bomb at PSNI officers as the children neared the school gates. The device exploded and injured two policemen and a police dog. After the incident the PUP's Billy Hutchinson said he was ashamed to be a loyalist. However, he says he continued to stand with the protesters every morning to show leadership. Anne Bill is a community worker and mother-of-two from Glenbryn. She was centrally involved in the Holy Cross protest, standing daily with the protesters and giving TV and radio interviews to defend their cause. She has no regrets about taking part. For her the Holy Cross protest had its roots in Protestant and loyalist disillusionment with the Good Friday Agreement.

"Community relations throughout all of Northern Ireland took a step backward because Protestants felt they weren't getting a fair deal under the Good Friday Agreement. People in Glenbryn kept telling the Government about attacks on their houses and how vulnerable they felt but we weren't being listened to. That is why people protested on the Ardoyne Road, the focus wasn't so much the school itself. You can't detach the Holy Cross protest from the high-level politics that go on in Northern Ireland. People on the streets see politicians at each others throats, so it's little wonder they give up all hope of resolving local disputes in a peaceful manner. The community in Glenbryn is in decline and it is fearful of Ardoyne. That does encourage a siege mentality. Glenbryn had no choice but to protest and I don't think people should apologise for that. If I had been a Holy Cross parent I definitely wouldn't have taken my child up through that protest, I would have walked in the back gates." But despite Anne Bill's assertion that the protest was aimed at the British Government it was the children and parents of Holy Cross Primary who suffered the trauma and violence of that protest. During the dispute people in Ardoyne became increasingly frustrated with the lack of progress in resolving it. Every morning the parents and children would line up at the junction of the Ardoyne Road and Alliance Avenue to be escorted to the school gates by police officers in riot gear. Parents resented being forced to line up and although the police stopped the protesters from getting within touching distance of the children abuse was still hurled. The PSNI and the then Secretary of State, John Reid's response to the protesters angered parents and the Holy Cross Board of Governors. A Holy Cross parent sought a judicial review of the PSNI behaviour at the protest. The parent's solicitor argued that the PSNI had afforded the children and protesters equal protection when in fact the children had a greater right to get to school freely than the protesters had to protest. At the time of writing the result of the judicial review was still pending. The gauntlet which had to be run was indeed daunting. Loyalists took to blowing foghorns and whistles as the children walked by, creating a frightening din. And parents claimed that some of the protesters held up pornographic images as the children walked by and sometimes urine was thrown. The pressure and tensions caused by the protest were exacerbated by the nightly violence. One of the central figures in negotiating a resolution was Fr. Aidan Troy who arrived as parish priest in Ardoyne shortly before the Holy Cross dispute began. As head of the Board of Governors at the school he showed his solidarity with the parents and children by walking with them to school every day. Fr. Troy was a Catholic priest of some thirty years and head of the Passionist Order in Europe having served in war-torn countries such as Rwanda and the Congo. A Baptism of fire' is how he describes coming to Ardoyne.

"I really found it hard to comprehend the hatred that was shown to the school girls. It shocked me and I felt such pity for these lithe school girls who were being exposed to such hatred on a daily basis. I walked with them and because of that I was spat on by the protesters. They held up posters accusing me of being a paedophile and they showed the children pornographic images. The intensity of the protest was hard to comprehend; I don't think people can really understand that from watching it on television. It was a brutal period of time when every morning and every afternoon was an ordeal for the parents and the children. Everyone in the community was affected by it, but the parents and the children showed great dignity in coming through it. I remember seeing fathers and grandfathers walking up with their little girls and all sorts of abuse was being hurled at them. They must have been tempted to take the law into their own hands but they maintained a dignity and a courage that is rarely seen." North Belfast Independent Unionist MLA Fraser Agnew concedes that he too was "appalled by the gauntlet of hate" that developed.

"The protests at Holy Cross were self-defeating. I understood why they were taking place. I wouldn't say that all Protestant violence was reactionary but a lot of it was. What happened at Holy Cross was a reaction to the fact that Protestant residents were denied access to local facilities [in Ardoyne] such as shops, Post Offices, children's playgrounds, etc. They were denied the most basic rights by pure intimidation. People were actually attacked, including pensioners. And Protestants genuinely felt that this was an orchestrated campaign to drive them from Ardoyne and that absolutely nothing was being done about this. And this campaign was under the control of so-called community workers - and the message was 'get the Prods out of Ardoyne'. In the first two weeks of the protest that restarted in September 2001, 15 children left the school and there were reports that the school would have to close because of falling numbers. Meetings between the Board of Governors and the protesting Glenbryn residents, who were then known as CRUA (Concerned Residents of Upper Ardoyne) took place. In total five face-to-face meetings were held but little progress was made. Fr. Troy describes the meetings as difficult and says the structure of CRUA presented problems.

"The meetings never descended to any personal abuse but they were most certainly difficult. We also felt that the whole way in which CRUA went about making their decisions hampered the whole process. They had to report back to the entire community and tell them what was going on. That left them open to being forced out of any decisions they were going to take and so progress was very slow. We had our final meeting a few weeks before the protests ended and we wanted to discuss how we would approach security of the children and the parents. But that was the last time we had any contact with them during the protest." Tentative steps to restore relations in the wake of the protest were made through the North Belfast Community Action Unit. Set up to foster inter-community talks it focuses on social and economic issues of interest to Ardoyne and Glenbryn. Nevertheless, community workers from both sides admit progress has been slow. Anne Bill, who is regarded as one of the more moderate voices in Glenbryn, says her counterparts in Ardoyne are hard to take at face value.

"On the occasions when we meet with them I always get the feeling that they are playing games with us. I have met people from other republican areas of the city and they always seem more genuine. I don't know if that is because we have so much conflict with Ardoyne or whether that is the way they actually are but it shows that relations are pretty bad." Comments such as these highlight a fundamental feature of Interface areas - that people in these situations hold such a well-honed suspicion of their nearest neighbours, their nearest threat', that they see them as uniquely distrustful and untrustworthy. And so these people have more time for absolutely anyone else over them. This seems to be a universal trait in such circumstances, regardless of rights and wrongs. One of the effects of the Holy Cross dispute was the demarcation of territory along the interface. The Ardoyne Road which connects Glenbryn to Catholic Ardoyne was festooned with flags and emblems at either end. On the Catholic side tricolours were flown from lampposts, while at the loyalists end UDA flags, Union Jacks and even Israeli flags fluttered. Fraser Agnew acknowledges this territorial aspect of the North Belfast situation in general and the Holy Cross dispute in particular. He also suggests that this aspect is more pronounced as a result of one feature of The Belfast Agreement.

"There is a battle for territory in all of this, where you get paramilitaries on both sides trying to control areas for their own criminal reasons and both sides hide under the cloak of their supposed causes. One of the problems of the Good Friday Agreement was that prisoner releases put many of these people back on the streets free to intimidate their areas." While the dispute was eventually brought to an end, the street violence, however, continued. In ending the dispute the Glenbryrn residents said they would await the outcome of a report by the First and Deputy First Ministers of Northern Ireland. They wanted the report to recommend a security gate be erected at the junction of Alliance Avenue and the Ardoyne Road. The report was also to deal with traffic calming measures and greater security measures for the Glenbryn area. Holy Cross parents had always opposed a security gate saying it would cut the school off from Ardoyne and leave them vulnerable to attack, In the event the report did not recommend a gate be built but the loyalists were prepared to accept this although the protesters referred to the ending of the protests as suspension'. But the Glenbryn residents' refusal to rule out another protest added to a sense of insecurity in Ardoyne. Parents and the Holy Cross Board of Governors wanted loyalists to definitively rule out any further protest out side the school, something they refused to do. A month before the protest was called off the Department of Social Development announced a housing redevelopment package for Glenbryn. This move infuriated nationalists, particularly in north Belfast, where almost 80% of people on the housing waiting list are Catholics. They viewed the package as a buy-off for Glenbryn residents. Ardoyne Sinn Féin councillor Margaret McClenaghan says the common perception was that loyalists were being rewarded for intimidating schoolgirls.

"The money involved in the housing package and the way it was announced meant people could only reach one conclusion, that loyalists were being bought off. They refused to listen to reason to call off their protest so the British government simply bought them off with cash. Nationalist housing in north Belfast is chronically overcrowded and under-funded, yet here we are with Glenbryn having millions pumped into it." One Protestant community activist expressed a different perspective.

"There is no victory for our area despite all the hype. It is actually a strategy of social political engineering between the NlO and the Housing Executive, to solve the issue of interface tension. Dr Pete Shirlow of the University of Ulster who has researched interface areas in Belfast says that housing disputes are a key component of such disputes.

"It can even boil down to things like how big a garden is. For instance in Protestant areas there are more houses than people to fill them so when the Housing Executive redevelops them they tend to build then with bigger gardens and more space around then because the volume of housing isn't so important. But when nationalists look at this they see Protestants getting luxury houses while they are living in overcrowded and cramped conditions." For months after the Holy Cross protest ended police and British Army Land Rovers and Saracens sat out side the school and at the junction of Alliance Avenue, but eventually parents were able to walk their children to school without a police and army escort. Fr. Aidan Troy describes the weeks and months after the protest as tense.

"Understandably parents still felt that they were very vulnerable to attack in the weeks afterward. No-one knew for sure what was going to happen but at least the immediate pressure of the protest was off. For the first time the parents weren't walking up in double file and altogether at set times. They could walk up freely and the children didn't have to huddle beside their parents. I can still remember the night the protest was called off. It wasn't until around midnight that the residents said the protest wouldn't be going ahead the next day. There was great sense of relief and joy and of sadness. People were crying, it was the build-up of pressure over months when they were just trying to keep their heads above water. During the protest some of the schoolgirls had been put on heavy tranquillizers such as Diazepam. Kids as young as eight and nine were actually on tranquillisers because of the trauma they were experiencing in their own homes and going to school in the morning." Parents told how their children had been wetting the bed and had started to throw tantrums and become withdrawn. When teachers in the Holy Cross school asked P6 girls to draw a picture many had drawn mothers and fathers crying, surrounded by people with angry faces. Brendan Bradley heads the nearby Survivors of Trauma group which deals with victims of violence throughout the Troubles. He says that the trauma experienced by the children is almost without parallel in the history of the Troubles.

"What is amazing about this is the fact that the girls, some were only four years old, were subjected to abuse and protest every day and every afternoon they went to school, It wasn't as though this abuse lasted for a couple of days or was a one-off, it went on for months. Many needed counselling, some long-term counselling, in the wake of it all. Parents told how their daughters had changed from being fun-loving to being very withdrawn." The trauma posed by the protest was made worse because some of the children lived in Alliance Avenue, which was itself the scene of nightly riots. Houses along the peace line with Glenbryn were attacked with pipe bombs and petrol bombs. Roisin Keenan lived on Alliance Avenue during the Holy Cross protest. Some time afterwards she moved out of the area after a third bomb attack on her house. Her only daughter Fionnuala was just three-years-old and in the Holy Cross playgroup when the protest began in June. Every day until the end of November mother and daughter walked up the Ardoyne Road through the protests. But Roisin says the continual attacks on her house at night-time made her time in Alliance Avenue a living hell.

"At the time I thought Fionnuala would be too young to be affected by the protest but I was very wrong. Looking back I don't know how we did it, how we actually managed to walk through that wall of noise and protest and hatred every morning of life. I think it is only afterwards when you look at a situation that you realise the stress you were under. We took her to the play-group and it was funny because you nearly expected to see the same faces shouting at you every morning. But I don't think we could have coped if it had have went on for much longer." Roisin's home was attacked with stones and petrol bombs on countless occasions, twice with pipe bombs which exploded in her backyard and once with a hoax device. Eventually she was only able to sell her house through the Special Purchase of Evacuated Dwellings Scheme, a government scheme which buys houses from people who were victims of intimidation and designed to ensure they receive the full market value for their properly. When the first attacks on Alliance Avenue started in April the upper part of the street where Roisin lived was not protected by a peace line. The peace line at the top of Alliance wasn't built until five months later. Until then her tormentors could climb through her hedge. Another feature of interface conflict is the confusing maze of claim and counterclaim, not just relating to incidents that have taken place, but also as to whether certain incidents took place at all. For instance, Glenbryn residents complain about a BBC report based on a Sinn Féin claim that 200 loyalists had attacked Catholic homes, which the residents insist never happened. The police confirmed the resident's denial. Such are the levels of suspicion across Northern Ireland however that many Catholics would, rightly or wrongly, expect the police to back up' by loyalist claims. It is a common assertion in Protestant areas that the media is frequently hoodwinked' by republican propaganda. Some loyalists would go further and suggest that certain elements of the so-called independent' media are actually nationalist sympathisers not being hoodwinked at all but are wilfully putting their own slant on events. Whatever the truth, most loyalist communities resent their portrayal in the reporting of interface areas, believing that their side almost always comes off worse. News organisations would deny such suggestions vigorously and would claim to be alive to the manipulations of competing propaganda. But with the facts often difficult to state with certainly, a reporters own judgement often plays a bigger part in the report than he/she intended. And while that judgement might be utterly impartial, both republican and loyalist communities can feel alienated by the judgements of people who do not face the same daily challenges as they do. Three decades of violence have created a climate of fear, where suspicion, mistrust and resentment of each community grew. To many the 40-foot-high peace line was the British Government's crude response to those problems. The British Government argues the peace lines are a security measure designed to protect lives and stop riots. Gerard McGuigan is a community worker in Ardoyne. He was one of the first Sinn Féin councillors elected to Belfast City Council and has lived in Ardoyne all his life. He says that when the peace lines first went up in 1971 few people took much notice of them.

"At that stage it was non-stop riots with the Brits; people weren't thinking of the future and nobody thought the conflict would last until the 1990's. The Brits were taking over empty houses in Alliance Avenue and using them as observation posts so a fence here and there seemed insignificant. The Alliance Avenue peace line just grew like a tree. Once it started going up people started testing it for weak spots and that led to it being extended further. A lot of the time the peace line was actually no more than a rickety fence, there were holes all over it and it was more symbolic than practical. To understand the peace lines you have to understand the early days of the Troubles and the population shifts that were taking place. Catholics were being burned out of their houses and Protestants were consolidating their own strongholds. But what the peace lines did was to consolidate divisions without actually offering people much security. In 2003 Catholics in Alliance Avenue are still being attacked by loyalists on a regular basis. No Catholic in Alliance Avenue has ever felt safe from loyalist attack and you just have to look at the number killed there to see why." Gerard McGuigan feels that the peace lines make it more difficult for the Catholic community in Ardoyne to grow naturally.

"I'm not saying the peace lines haven't offered the residents a degree of security, even if in many ways that was mainly psychological. But they have also added to a feeling that the two communities don't need to talk to each other. You have to remember that the DUP still doesn't talk to Sinn Féin and that mentality filters down to their own people on the interfaces. People should also remember that the peace lines never stopped attacks. In fact UDA gunmen in Glenbryn would use the wall as cover to fire into Ardoyne on the Twelfth of July. They could hide behind the fence and launch attacks and if nationalists came out the British Army and RUC would swamp the area and begin raiding Protestant houses. One such attack claimed the life of 63-year-old father of 13, David Braniff. A Protestant convert to Catholicism he was shot dead by the UVF as he knelt saying the Rosary in his Alliance Avenue home in March 1989. Even after the ceasefires of 1994 people continued to be murdered in Alliance Avenue. On 31 October 1998 Brian Service, a 35-year-old Catholic, was shot dead by loyalist gunmen as he walked along Alliance Avenue. He was the last victim of violence that year, Such attacks reinforced the fear factor for Catholics living in Alliance Avenue. In common with most interface areas both Ardoyne and Glenbryn suffer from high levels of socio-economic deprivation. A report carried out by the University of Ulster in 1992 showed that 69% of people living In interface areas earned less than £5,000 annually, compared to a Northern Ireland average of 45%. Thirty-one percent of the community was unemployed, compared with a Northern Ireland average of 14% and 41% received income support, compared with an average of 21%. An undeniable aspect of the violence around interface areas centres on perceived territorial expansion. Perhaps surprisingly, given the record of attacks against Catholics in Alliance Avenue, it is the loyalist side that is most keen to see the peace line extended. One of the key demands made by the Holy Cross protestors was the erection of a security gate at the junction of Alliance Avenue and the Ardoyne Road, the invisible border between Catholic and Protestant Ardoyne. In effect the gate would have meant Glenbryn would be almost entirely cut-off from the rest of Ardoyne. Protestants are also most keen to have the height of the peace line raised. According to North Belfast MLA, Billy Hutchinson, a leading member of the UVF-aligned Progressive Unionist Party, this is because Protestants fear Catholics are intent on driving them out of the area. It is a view shared among Protestants across the North, leading them to adopt a siege mentality and view any outward sign of compromise as a devilish ruse dreamt up by republicans. Demographic changes in north Belfast mean that Protestants there feel the pinch of a dwindling population more than most. Between 1981 and 1997 the Protestant electorate in north Belfast has shrunk by almost 20,000. Since the ceasefires of 1994 Glenbryn's population has plummeted from more than 3,000 people to just over 900, according to community workers in the area. That decline is symptomatic of working-class Protestant areas. For example, in 1969 72,000 people lived in the Greater Shankill area, by 1996 there were only 20,000 left. Community workers in the Shankill area explain that this decline is due to massive demolition of many streets by The Northern Ireland Housing Executive, with only a fraction being replaced, despite promises to the contrary. The rise in Sinn Féin's vote in North Belfast has also had a disconcerting effect on Unionists. In the 1992 Westminster elections Sinn Féin polled 4,693 votes in North Belfast or 13.1% of the vote. In the 2001 Westminster elections Sinn Féin polled 10,331 votes or 25.2% of the vote. The population shift and the emergence of a nationalist consensus are critical to understanding why territorial disputes are central to the conflicts that surround peace lines. The end of industries which traditionally employed Protestants, such as the Harland and Wolff shipyard, and the availability of cheaper and better housing on the outskirts of Belfast have tempted many Protestants to move from areas such as the Shankill and Glenbryn. However, Unionist and loyalist politicians prefer to see demographic changes as part of a republican conspiracy to drive them from their areas. Billy Hutchinson says loyalists in Glenbryn feel under siege.

"If you look at Glenbryn it is really a very small community surrounded by a much larger republican one. People there are hemmed in and they see Ardoyne expanding constantly. Continual talk of the rising nationalist population makes people feel that even more. To Protestants in Glenbryn it feels that if they give away any more ground they will be wiped out as a community. People there are always on the defensive and feel their plight is ignored. The protest was a disaster in terms of putting their cause forward but it was a genuine expression of their anger and frustration and fear over what is happening in that part of North Belfast." However, Billy Hutchinson rejects the view that Protestant areas are in demographic decline because of republican aggression.

"I think it has more to do with economics and the loss of centres of employment than anything else. What has happened in Glenbryn is typical of Protestant areas all over Belfast. Since the late 1960's Protestants have been moving to the outskirts of Belfast so it isn't surprising that today there is a lot of dereliction in inner-city working-class areas. It is definitely true though that Unionism in general has felt less confident for the last 35 years than it ever has done. People are apprehensive about the future, they don't know what it is going to bring and often that fear can manifest itself in violence. Before the cease-fires that anger expressed itself in shootings and bombings, and even if people didn't go out and join organisations like the UVF or the UDA they felt that their interests were being looked after by them. Since 1994 people haven't had that and I believe that is part of the reason for the rise in sectarianism at the interfaces. No-one is going out and doing the shootings or the bombings so people from interface areas are more likely to vent their anger on each other. The sectarianism that exists in the upper-class parlors of Cultra and places like it is no less vile than the bigotry that exists in working-class areas. With the middle-classes it might find expression in the form of discrimination in jobs but working-class people don't have those resources so the only expression of it is to riot and to inflict pain and violence on each other." Sinn Féin's Gerry Kelly, a North Belfast MLA (with paramilitary convictions as has Hutchinson) says the violence surrounding Glenbryn and the Holy Cross blockade are a microcosm of the whole conflict in the North. As the senior Sinn Féin member for North Belfast he was involved in behind-the-scenes negotiations with the parents of the Holy Cross children and with community leaders from Ardoyne.

"Over the past four or five years the focus of conflict has switched to interface areas in Belfast. This has meant attacks on homes on a nightly basis and the re-emergence of the UDA on the streets, directing these riots and attacks. The UDA used the Holy Cross blockade and other interface areas as a way to destabilise the peace process, to try and derail it. Their tactics were very simple - to cause enough instability on the streets to make sure political progress couldn't happen. Trying to resolve it took up a lot of time for a lot of people. I was working at Stormont during the day, when I could, and going to Ardoyne at night time to try and stop the trouble, that cycle went on for more than a year and it was clear what the intent behind it was." Fraser Agnew, the Independent Unionist MLA for North Belfast agrees with the statement that "there has been an orchestrated pipe-bombing campaign by loyalists against Catholics, designed to intimidate them out of their homes in North Belfast". However, he adds that a similar situation existed in reverse in Whitewell and Short Strand, where Protestant residents were under attack. He accepted that Catholics there might see it differently but he insisted that there was validity in the Protestant perception that they too were under siege' in certain areas. Agnew accepts that his analysis might not seem fair to nationalists but he felt that as an elected representative, elected by Protestants, that his first responsibility was to fulfil the leadership function of bringing like-minded people with him. He appreciates that this logic also applies to republicans and this is why republicans can seem unreasonable to unionists. And this may be why republicans do not go as far as Unionists would like on issues such as condemning republican rioters and decommissioning. He further points out that in North Belfast, the INLA and CIRA are waiting in the wings, hoping that the Provos' would take one step too far and leave their people' behind and so he appreciates the constraints on them. Sometimes the violence had a destabilising effect on the political manoeuvrings in Stormont. On one occasion republican gunmen shot and wounded a Protestant youth from Glenbryn during the height of a riot. He was badly injured in the leg. Unionist politicians demanded the Secretary of State revoke the IRA's ceasefire status and ban Sinn Féin from office. However the source of the gunfire could not be definitely proved and the calls came to nothing. For Gerry Kelly one of the key factors contributing to the violence is the DUP's refusal to talk to republicans.

"The DUP have refused to negotiate with Sinn Féin for the past 30 years. Even now, almost ten years into a peace process, they are still doing the same thing and that is very dangerous. They are sending out the message to loyalists that it is okay not to talk; in fact it is better not to talk. Now if people close down dialogue as an option in a conflict situation then one of the other options that become viable is to engage in violence. They are effectively working against reconciliation and the UDA is using that idea to encourage attacks and violence." Despite the divisions both sides agree that Ardoyne and Glenbryn would benefit in the long-term if the peace lines were taken down. However, no-one can agree on how that will happen or the conditions that will lead to it. One measure adopted to improve mutual security at the Interface Area was to install surveillance cameras. But though that was welcomed by Glenbryn Residents, Sinn Féin spokesmen objected as they saw it as an intrusion' on their community's privacy. Several were latter cut down by gangs wielding angle grinders. Alban Maginness of the moderately nationalist SDLP and the first Catholic Lord Mayor of Belfast when he took the post in 1998, says the peace lines are a sign of failure. And he says that if the governments can't get it right at the Ardoyne interface they can't get it right anywhere. As north Belfast's most senior SDLP member he argues the spread of the peace lines went almost unnoticed during the height of the Troubles, creating no-go areas for Catholics and Protestants.

"Before the Troubles a lot of what are now termed the interface areas of Belfast would have been mixed. Areas such as Newington and Ardoyne would have been home to Catholics and Protestants. Although people thought of areas in terms of Protestant and Catholic there would have been much less segregation. Today in north Belfast almost every area is either predominantly Protestant or Catholic. We really need to find a way out of that situation but there are no easy answers. Violence destroys communities and in my opinion a lot of the violence that happened in the past two years could have been avoided. If the police and army had been much more pro-active in trying to stop loyalists, from where the great majority of the violence was emanating, then it would all have been over much quicker. What happened at Holy Cross was wholly unacceptable but what is happening all over Belfast is that sectarianism is on the rise." The wall which separates Ardoyne from the Crumlin Road is supplemented by a permanent security gate at the bottom of Flax Avenue. In the 1980's Orange Bands would stop at the Protestant side of the gate to bang their drums and play loud renditions of the Sash. Riots frequently broke out. Michael Liggett is a community worker in Ardoyne. He says the wall has inhibited the development of Ardoyne as a community.

"We are hemmed in on all sides, we can't stretch out and grow like other communities. The problem isn't a lack of space; it is the peace wall, if that is what you want to call it, keeping us ringed in. Most of the Crumlin road lies derelict and part of Ardoyne itself has been chopped off to create a buffer zone. Overnight streets that housed hundreds of people were literally cut from the map because of British security considerations. Where does that leave this community? We have a chronic housing need in this part of north Belfast but our community is totally enclosed by walls, it means that new houses can't be built and when they are it is a question of taking away what little free land there is for more housing. That means kids have absolutely nowhere to go and play. We are supposed to be in a peace process at this point and it is time for the walls to come down. Or is the British Government telling us that they think loyalists are still going to come in and try to assassinate us?" Although people in Ardoyne object to the security wall which runs along the Crumlin Road it has meant loyalist gunmen have had greater difficulty in targeting nationalists from the area. Likewise Protestants living in the streets behind the wall on their side of the road give reluctant support for such protection as the wall provides against attacks from Catholics. From the early 1970's, both republican and loyalists gunmen emerged from their own side of where the peace line now is and inflicted terror on the other sides community. The Crumlin Road is regarded as one of the most dangerous roads in north Belfast. It gained its grizzly reputation in the 1970's when loyalists from the nearby Shankill would cruise along in cars looking for unsuspecting Catholic victims. In the late 1970's it became a pick up zone for the infamous Shankill Butchers Gang. Victims were bundled into cars in the dead of night before being taken away for torture sessions at the hands of the notorious UVF gang. Although today most of the paramilitary violence that blighted this part of North Belfast has disappeared, both communities still live in fear. An uneasy peace exists, particularly during evening hours. Protestants behind their side of the wall still complain of regular assaults with missiles thrown over the wall, or direct attacks by nationalists using Protestant pedestrian access in the wall and retreating back to their own territory. One direct result of these attacks has caused problems for a local housing association, which has difficulty allocating houses adjacent to the peace line wall, despite a pressing housing need in that Protestant area. Residents say that the reluctance of the police to pursue the intruders into the Ardoyne has only compounded Protestant insecurity.

If there were obvious solutions to these interface area's problems, we'd know them by now. What is apparent however from the interviews for this book is the high level of unreported grassroots activity focused on at least reducing tensions, even if a durable, mutuaI acceptable solution to the whole "peace line" question is as elusive as ever. This determination on the part of the communities and their elected representatives succeeded, according to many accounts, in ensuring the summer of 2003 was a little less violent then the immediately preceding years at least. Meanwhile, the fundamental issues demographic, political, religious and national - continue to test these communities to the limits of endurance.

|

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||