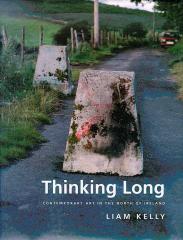

'Thinking Long: Contemporary Art in the North of Ireland' by Liam Kelly (1996)[Key_Events] [Key_Issues] [Conflict_Background] The following extracts have been contributed by the author Liam Kelly , with the permission of Gandon Editions. The views expressed in this chapter do not necessarily reflect the views of the members of the CAIN Project. The CAIN Project would welcome other material which meets our guidelines for contributions.  These extracts are taken from the book:

These extracts are taken from the book:

Thinking Long:

Published by Gandon Editions as the third volume Orders to:

This chapter is copyright Liam Kelly 1996 and is included

on the CAIN site by permission of the author and the publishers. You may not edit, adapt,

or redistribute changed versions of this for other than your personal use

without the express written permission of the author or the publisher, Gandon Editions. Redistribution

for commercial purposes is not permitted.

From the back cover:

THINKING LONG examines art practice in, and in relation to, the North of Ireland during a period of acute political and social change - from the late 1970s to the early 1990s. It demonstrates that artists during this period sus tained a penetrating enquiry into Irish cultural tradition and identities, producing art that is much more didactic and discursive than at any other time in Northern Ireland's short and problematic history. The book delves into such practice for compelling issues, prevailing tendencies and preoccupations, rather than attempting to analyse and document by way of formal categories, such as painting, sculpture and photography. Consequently, it is thematic in approach and comprehensive in range - the work of some 80 artists in a wide variety of media is surveyed - allowing the reader to grasp the general concerns and characteristics of both time and place, and also to follow developments in the work of individual artists. In contrast to other studies which examine and document the visual arts in the North of Ireland prior to 1977, the author takes the view that the artistic discourse is not, as a matter of practice, co-terminus with its political bound ary. Therefore, while the main focus concentrates on artists who were born, have lived and worked in the North of Ireland, the study also features a number of artists who have produced work which relates - at times contro versially - to Northern Ireland. THINKING LONG demonstrates that the political troubles in the North of Ireland, acting as an urgent and compelling catalyst, have set a shared, focused, common agenda for an articulate and socially responsible new generation of artists. The book engages with the following themes:

- the psychographic fabric of the city - abstract art and the tensions and turbulence of the times - the violated body as the new and persistent anatomy - the petitioning of nature and ancestral memories

BRIAN O'DOHERTY Liam Kelly's devoted rehearsal of each artist's presence, purpose and practice is cumulative. Step by step he builds their joint activities into something indispensable: a conviction that a particular time has been observed. Does this amount to much? Of course it does. What is observed is changed. Such records and investigations as Kelly's are part of a period's consciousness, the referent within which work is made and which contributes to its legibility. That period has a political consistency, as we know. Its conflicts have been economic, sectarian, nationalistic and class-bound. It has knitted its social matrix out of injustice and the irrational, out of polarised extremities and vulnerable moderation. It has had, as such conflicts do, an intense educational value, but much of the education has been in the cultivation and transference of hate. To make visual art in such a context is to initiate, however indirectly, a social action. Some degree of repression is (somewhat smugly) said to serve as a stimulus to the artistic imagination. It depends on the degree. The destruction of cultures and of the past - to take one large (the Chinese cultural revolution) and one specific example (the sack of Vukovar) - can be so extreme that survival pre-empts all else. That is not news in a country which has had its mediaeval period virtually wiped from the artistic board. But the low-grade war in Northern Ireland - with its sporadic dialectic of action and reprisal, demonstration 'and counter-demonstration - leaves enough stable ground to plant an easel on. There is always the war - and something else. That is, it is possible to escape from the overwhelming sense of a lurking and sudden ideological violence. But there is a price to be paid on both sides of that particular fence. For once the civil war spilled over into everyday consciousness (the sound of the helicopter is its heartbeat) it is, for the artist, the best of times and the worst of times. You have a theme, a great gift, an ambiguous theme surely, but a theme indeed. You can't avoid it. So the questions ask themselves of each practitioner: Do I have permission to avoid this issue? If I use it, is it using me? What are my responsibilities to this matter, to myself, to my work? You discover that response to any oppression generates its own cliches. The darkness in your midst, like the cuckoo's egg, evicts a whole family of emotions and strategies that more peaceful times engage. To me a signal fascination of Kelly's book is watching/reading the responses to this dilemma - the devises summoned, the ideas brokered against the liberal imagination (since the artists seem to be of that persuasion), the loading and unloading of symbols, the conception of place. Which is why Kelly's work is important. He has brought together, with an ecumenical tolerance, a range of responses, the hard and unyielding engagement of the gifted with the circumstances of their gift. And thus is crafted the indispensable convexity of memory and imagination - the echo chamber we all sound: history. As one who grew up in the 'fifties in a country with a fractured cultural identity, I remember searching for what Kelly provides here: a sense of the past - a cultural history, if you will that could contribute to an understanding of my circumstance. History, of course, is a slut that accommodates any projection; facts dissolve, truth is relative, and the winners take all. Most of us are in search of illusions with a respectable enough relationship to historical fact that we can maintain them without embarrassment. I see Kelly's careful accumulation of artists' responses as a palimpsest recording several impressions of historical weights and densities. In mediating much of this, the Northern Ireland Arts Council has shown a judicious delicacy of touch. Northern Ireland is not unique in its conflict and emotions. It is unique in the way they shape themselves into a particular profile. Many places carry their burden of lost heroes, official and unofficial murderers, inspired leaders, innocents deprived of their most precious possession, life itself. There are always ideologues and nationalists, religious absolutists and those who hear the voices of different Gods. Always with us are the pain of memory and the righteousness of contrary causes, the mixing of stocks and the breeding out of pure strains, the blurred lineaments of atrocity and the submission of the abused. There are those who maintain a bridgehead against dishonouring traditions that demand respect. Everywhere, there is a reservoir of anger that injustice steadily fills. And in Northern Ireland, as elsewhere, there is the paradoxical traffic of minorities and majorities that switch one to the other depending on how they are measured, is it fair to say that in Northern Ireland, a harsh realism forestalls the future with a present that burns brightly enough to illuminate some previously unvisited corners of the imagination? Does that imagination define itself in Kelly's pages: wary, on-edge, ironic, thoughtful, laconic like its speech, sometimes angry, sometimes inspired? In the domain of visual art, places have become more assertive. The primacy of the legendary city (from Rome through Paris to New York) has been eroded by the withdrawal of the consensus that gave it magisterial status. We have witnessed a kind of aesthetic diaspora since the waning of ideology. Any place is important if you make it so. The Belfast-Derry axis is important. For all its burdens, why do I persist in seeing Northern Ireland as a magical place, extraordinary in its cultivation of its history, unusual in its poets, its patriots, however defined, its unforgettable siege, its migrants who have given the United States philanthropists and presidents, and above all, its potential? Even as I read Kelly's book, new traditions are forming. Visual art has won itself a place at the table, and a tough table it is to sit at.

In times of social unrest, symbols become targets. They are dangerous

in politics, but poets and writers can't do without them, or their

cousin, metaphor. If I think of the Republic as a Big House which

the revolutionaries took over, became caretakers, then tenants,

then masters, then quarrelled and tore it down, rebuilt it until

it fit their needs, what metaphor offers itself that in that particulate

and troubled geographical fragment that is Northern Ireland? It

is in the toils of intense process. It is in motion, ploughing

through turmoil and hazard. Could we imagine a phantom reconstruction

of Harland & Wolff's masterpiece? And launch it burdened with

the contradictions of its place of origin. Can we see this vessel

moving out and on not to oblivion but, in its metaphorical incarnation,

arriving however battered - at a safe port?

LIAM KELLY This book was commissioned by the Arts Council of Northern Ireland to follow on from their previous two publications, Art in Ulster I and Art in Ulster 2. It examines art practice in the North of Ireland during a period of acute change (late 1970s and 1980s), both locally and internationally, and in an age of cultural eclecticism and pluralism. The book differs from its immediate predecessor, Art in Ulster 2 (published 1977) in as much as the period under review radically differs, and demands a different approach. It can now be more fully appreciated that Northern Irish artists during the 1980s sustained a penetrating enquiry into Irish cultural tradition and identities, producing art that was much more didactic and discursive than at any other time in Ulster's short and problematic history. My approach, then, was to delve into such practice - produced by an increasingly more numerous group of artists - for issues, prevailing tendencies and preoccupations, rather than to attempt to analyse and document, by way of formal categories, such as painting, sculpture, photography et al. Consequently, this study is thematic in approach and comprehensive in range, allowing the reader to grasp the general concerns and characteristics of both time and place, but also to follow developments in the work of individual artists. This dual intention is reflected in the way some chapters are divided into sections. As a document of art activity of the period, it is hoped that it might prove a useful work of reference and possibly provide a solid basis for further research. Such a discursive practice has already been affected by the international dialogue of an intensely text-related epoch. To what extent artists here have read and discussed, in any extended way, the theories of a philosophical activity such as deconstruction, as postulated and refined by thinkers such as Jacques Derrida, I do not know. I do know (through many discussions with many artists) that, as elsewhere, the residue of concepts such as difference' and 'logos' (related in an Ulster context to cultural identity, colonialism, text, truth and image) has had an appropriate home run here. With regard to the limits of the context for this study, I have taken the view, in contrast to Art in Ulster 2, that the geography of the artistic discourse related to the visual arts in Northern Ireland is not, as a matter of practice, co-terminous with its geographical boundary. Therefore, while importantly the main focus concentrates on artists who were born, have lived and worked in the North of Ireland, by necessity I have also examined a number of artists who have produced work or, in some cases, a body of work which relates, at times controversially, to Northern Ireland. In a book dealing with art so related to the problematics of place, it is difficult to know where and how to include non-indigenous artists who have worked or settled here for varying lengths of time and whose work may or may not relate in any way to a Northern Ireland context. I have, however, included those non-Irish artists who have contributed to the artistic life of the province, either by the nature of their practice, their influence in education, or their sense of communion within the tight circle of Ulster artists.

John Hewitt stated (c.l95l) that we, as yet, could not claim any

distinctive Ulster school of art. In the old fashioned connoisseurship

use of the word, that claim still holds true. However, the political

troubles in the North of Ireland, acting as an urgent and disturbing

catalyst, have set a shared, focused, if disputed, common agenda

for an articulate and responsible new generation of Ulster artists.

Landscape has always been a dominant theme in Irish art traditionally, Ulster landscape painting had mostly been a celebration of the formal features of the Ulster countryside -the ever-changing, always moisture-saturated skies; the rolling drumlin hills and lush meadows; bogland and bog pools. These landscapes were often painted without figures, except where anecdote or the figure as a formal prop were important, as in the work of William Conor or Tom Carr. The present generation of artists are not content to celebrate landscape, and regard it not as a given but a constructed reality, and, as such, problematic. Their approach is no longer a topographical journey, but a subterranean quest. Hence the need for an art practice that was an open-ended but interrogating dialogue. The craft pleasures of picture making gave way to a series of land-mining strategies. Section I sets up an enabling context for a discussion of the work of Dermot Seymour, Chris Wilson, Willie Doherty and Paul Seawright. It relates their practice to other non-Irish artists who have exhibited in Ireland (a number at the Orchard Gallery in Derry) and who, in some cases, have built up a body of work related to Ireland (Terry Atkinson and Rita Donagh). The use of text as a strategy in various ways links all the artists under consideration. The section also considers the work of these artists in relation to a literary context, making connections in particular with the playwright Brian Friel and his reflections on the problematic nature of translation and language. Also within this context, the rope drawings of expatriate Irish artist Brian O'Doherty, which have been 'installed' in Dublin and Belfast, are analysed. Section II adopts a different approach and surveys, in more depth, development and concerns of a group of artists (Kathy Prendergast, Diarmuid Delargy, Cohn McGookin, John Carson, Clement McAleer, Fergus Delargy, Micky Donnelly, Catherine Harper, Marie Barrett, Ronnie Hughes, Paul Sherrard and Victor Sloan) over the time scale covered by the manuscript. Extending out of the late work of Jack B Yeats, the concept of 'art as itinerary' has proved a useful device for a number of these artists working in different media, concerned with Irish issues as land-related. By way of acts of subversion or interrogations of tradition, all the artists in both sections engage with what might be termed the cultural mapping of the psychic landscape.

Words Pressed Against the Pane

Irish art has been both praised and criticised for having a literary bias. And it is true that there is an easy relationship between poet and painter in Ireland. The word 'Rosc', chosen for the former international exhibition held in Dublin, means 'poetry of vision' in Gaelic, and testifies to the literary thinking of the original organisers. It is curious then that some Irish artists have never produced any manifestoes so beloved by modernists. Things are changing however. The soft lyrics, once sung, have given way to a new agony in the garden. There is now more open examination of Irish cultural tradition. And within this tendency, text has become important, either as carefully considered titles or words superimposed on images, or words and slogans worked up from the landscape or townscape itself. Micheal Farrell is historically important here.

Towards the end of the sixties and early seventies, Farrell's

work began to change. The political troubles in Northern Ireland

had already begun, and Farrell's work, which, to date, had no

political connotations, began to respond to the tragic situation

in Ulster. A series of abstract works, his Pressé series,

which were purely formal studies, now began to take on meanings

that put the formal elements of his visual vocabulary to the service

of more politically significant and impelling content. The squelches

of pop juice now became blood, the once sterile language of the

Pressé series became the passionate Pressé

Politique. Anonymity gave way to personal identity. Variations on this theme continued to become more and more reflective on what it means to be Irish and an artist, rather than merely an artist. In Une nature morte à la mode Irlandaise (1975), we witness newspaper headlines of various tragedies, chopped up by the now fulminating Pressé elements and the use of witty and clever punning in the deadly appropriate French title on the concept of nature morre. In an interview in The Irish Times in 1977, Farrell reflected upon his artistic change: I became interested more in the literary aspects and less in the formal. It put me in a terrible jam, and rethinking the whole basis of my work took a long time. I've withdrawn from the international stream of art to a more human and personal style than before. I found in my big abstract works that I couldn't say things that I felt like saying. I had arrived at a totally aesthetic art with no literary connotations. I wanted to make statements using sarcasm, or puns, or wit, and all of these I could not do before because of the limited means of expression I had adopted.1Farrell was, by now, living in Paris, and from what his new domicile had to offer, he chose to deploy Boucher's painting of Miss O'Murphy (herself an Irish emigrant living in France, and one-time mistress of Louis XV) as a more potent symbol for the direction in which his artistic and personal concerns were leading. In one of this series [17], the artist lays our Miss O'Murphy like a piece of meat in a butcher's window, signifying the various butcher's cuts - 'gigot, forequarters, le cut, knee cap'. Here, by word-play, he both puns upon the name of the original artist, Boucher, and poignantly comments upon the savagery of the political system and its victims in the North of Ireland. (Knee-capping is a customary punishment carried out by the IRA for informers and the like.) The artist himself has said of these paintings: 'They make every possible statement on the Irish situation, religious, cultural, political, the cruelty, the horror, every aspect of it.'2 One should add to his list the exploitation of women.

Another source of influence for younger Irish artists has been

a series of English artists who have shown their own work at the

Orchard Gallery, Derry, during the 1980s, and who have juxtaposed

imagery and text, among them Kit Edwardes, Tony Rickaby and Terry

Atkinson. One work by Edwardes, which was shown in 1983 and was

in the form of an altarpiece, had pictures of English football

heroes (World Cup stars, 1966) juxtaposed with drawings of saints

and martyrs. This change in cultural deification and values was

offset by the statement: 'That which is phenomenal in British

history is the extent to which a people, insular, uninterested

in domination and expansion have yet spread the pattern of their

thought and rule over the world.' Edwardes was concerned with

the way government and state control can manipulate people in

a capitalist society; religion too was examined, particularly

on a psychological and sociological level. A series of images

from his booklet True Love Stories [19] show Edwardes

at his most direct - serious but light-hearted and humorous. They

lack the pretension and arrogantly precious quality of some art

of this kind.

Language, image, meaning and their inter-relationships were also the concerns of Terry Atkinson, whose work was exhibited in Derry in September 1983. The artist was a founder member of the art and language group of the late 1960s, part of the wider conceptual art movement. The work on show spanned the years 1977 to 1983. The themes ranged from the human and political aspects of World War I, through to the exploitation of the Third World by the West; the Falklands War; the Middle East crisis, media and news presentation. He has also produced a number of works related to Ireland. Atkinson's style was what might loosely be termed expressionist in character, and his intention was clearly didactic. He is an artist who demands a lot from the onlooker and in the exhibition catalogue, he developed, in essay form, his ideas about art, particularly the relationship between art and expression. He maintained that art is nor simply to do with sensory aesthetic experience or awareness which elicits an emotional response from the viewer, but that it has to do with thinking. He blames the modernist tradition for this separation, that art and language should be incompatible. He states: The artist feeler has come to enjoy such a premium in precisely the context of downgrading thinking. And making concrete this division has been the categories of sensitive craft skills and technical competence set over and against intellectual competence.For didactic reasons, then, he sees image and statement/text as being the solution to this dilemma. In one work for example [16], two cats are reclining on a table with a view of the dawn sky through a large window, somewhat in the style of Edward Munch. The caption states: Property Ad 1: Two fat cats on a peninsular breakfast bar at dawn in front of a picture window, beautiful views, a natural idyll, £750,000 - cats not included. This property is especially suitable for persons or families who like watching the dawn break or for insomniacs!Here, then, one's initial response changes from a sensory experience to reflection upon aspects of consumerism, materialism and advertising. Again, in the Blue Skies series of works [15], one is expected to change gear from visual 'feeling' to literary thinking. The blue dominates the battered face of a black boxer, whose head is covered by a towel and who is listening to music via earphones, with a pet rat running in some curious ladder device. The caption reads: Blue skies VI: after retaining his title, the champ, his cuts already healing, meets the media at his exclusive island retreat whilst listening to rock'n'roll, and with his pet rat running. For the fight the champ received 700,000 billion dollars.Some work of this nature, dealing with philosophical propositions and word associations, can all too often fall uneasily between significance and obvious pretension. The work of these artists, however, does nor rest easy and has an honest seriousness about it, inviting, as it does, the viewer nor only to reflect upon social and political issues, but also upon the nature of art activity itself. It is interesting to compare Atkinson, who is English, with Dermot Seymour, a Northern Irish artist. Seymour's lurid, ominous and displaced drumlin borderlands are also myth-laden, and words are used to explore conundrums, complexities and bizarre juxtapositions. Nothing seems to be what it is. If the Ulster problem is about territory, then it is about insecurities. Seymour brands and marks his absurd menagerie of sheep, cattle and pookas so that they only stray into his pictures, just as partisans mark and territorialise the Ulster countryside. His animals are always the ones who look on, silent witnesses to the persistent fact that nothing has changed; or they pick up diseases from the land, underlining a preoccupation of the artist - the idea of the sickness in the land. An example of the latter is Botulism over Mullaghcreevy (1985) [20], an intriguingly ambiguous painting in which it is difficult to tell if a reclining figure is resting or dead. In the mid-1980s there was a drought in Ireland, and seagulls which had contracted the disease botulism from eating off contaminated rubbish tips would fall our of the skies. Seymour has incorporated such an image as a metaphor for the persistence of death associated with his notion of the wounded land'. He has commented: ...there's a question mark over the figure lying there - is he dead, asleep, sick? Those are ambiguous conundrums thrown in to start this whole idea that nothing is ever what it seems, which, for me, is one of the ways of trying to come to terms with the complexities of place.4Seymour is fond of incorporating military insignia, flags and graffiti as other forms of marking and categorising, but it is the titles of his paintings that set the riddles off. His titles, however, do more than describe. They humorously extend the meanings by interlacing them, as in The Queens own Scottish Borderers observe the King of the Jews appearing behind Seán McGuigan's sheep on the fourth Sunday after Epiphany (1988). The words roll together the series of juxtaposirions in the imagery: military intrusion and surveillance; religious expression and rural circumstance. Seymour is also fond of the double take. Here again the titles assist, as in A Freisan coughed over Drumshat on the death of the Reverend George Walker of Kilmore (1988). The double take or reference may link a historical figure with a contemporary parallel. Here an inflammatory preacher (a historical legacy) is off-set by a bellowing cow which is suffering from brucellosis - indicated by the inflated shape of her neck - causing her to cough. In other circumstances, some of these cows eat fertiliser bags, which cause their stomachs to explode. The double take is then extended, since the IRA use fertilisers for their explosives. According to Seymour, being Protestant is not being allowed to think for yourself.5 He illustrates this in a series of paintings by depicting headless figures as a comment on fundamentalist or entrenched thinking. In Who fears to speak of '98? (1988) [22], the dominant symbol of Harland & Wolff is relocated on Napoleon's nose (a local term for part of the Cave Hill, visible from most of Belfast). Here, Free Presbyterianism stands over the free-thinking of Henry Joy McCracken and his associates. Belfast's Cave Hill is historically linked with Henry Joy McCracken, and Seymour ironically sees the same kind of people, who today work in the local shipyard, in many ways like those who would have signed the United Irishmen pact. The painting points to frustrated behaviour, and a soldier beetle symbolically drops from nowhere.

Ideologies like nationalism/republicanism/fundamentalism scare the artist, and it is here that Seymour differs markedly from Terry Atkinson. Atkinson's contrived titles arise from ideology -Marxist thinking and dogma; Seymour's titles arise naturally from the townland. The convoluted nature of local historical reference, anecdote and myth is interlaced into the titles like ratted lace - a world without end. The complications of our society come out of locations, like pookas at night. A crossroads is not just a junction, it is where someone was shot, a patrol ambushed, a 300th anniversary celebrated each year or where traffic is monitored or surveilled. That is the nature of the land question. Seymour's townland is always on the brink. In A Lysander over Ballymacpherson, County (L)Derry (1984), a figure floats in a world of optical displacement. Viewed from a spotter plane (a Lysander), a reclining female figure on the land is 'brought up' by the voyeuristic tendency of a British soldier on surveillance above. This was the first of a number of works that would probe the potentially wayward and dangerous nature of surveillance. Seymour has used the Ulster drumlin landscape to enhance his desired sense of vertigo and inherent instability. He has also isolated animals on offshore stacks of land. This is particularly evident in On the Balcony of the Nation (1989) [21], a painting which summarised his concerns up to that time, focusing on a dislocated world of imminent collapse and moral breakdown. Since moving to live in the West of Ireland, Seymour has continued to develop this imagery of disintegration, but now under even more dominating and luridly colourful skies. He also continues to be fascinated by anecdote, local history and circumstance - the grip and presence of the past as evidenced by the land. The blackened faces of the ancestral flock of Myles Joyce ponder over all of Maamtrasna (1992) deals with the locally taboo story of murder between feuding families in the nineteenth century, with ramifications into the present and with sheep, as always, the silent witnesses. But the lingering legacy of the North's political troubles still continues to intrude. On first moving to Co Mayo, he completed a 'peripheral' painting, Summer grazing on Innisclug under the weight of the western sky in the last decade of the 20th century (1991). A floating fertiliser bag is now seen above a forlorn cow on a stack, against an ominous sky, with Ireland written on it in Japanese, bound for export. It would seem that many other cows are also in danger. In Ireland, surveillance is a kind of national voyeurism where no-one is sure who is the watched or the watcher. It is an infinite regression of an image within an image within an image, like the structure of a Flann O'Brien novel or the open circular mode of traditional Irish music, Willie Doherty's work is central to questions of word and image, and he would have been aware of the work of those English artists referred to earlier. Doherty's practice stems from a desire to redress certain photo-journalist images of the war-torn city kind. But there is much more at stake than the 'how we see ourselves' antidote. The artist deals with concepts of the land, Irishness, self and otherness. And to do this, he presses words against the pane. Some of his images are appropriated from a second-hand reality, given to them by reportage. The overprinting of words pulls them back into a new existential state, where contradictions, ironies, subversions are at work. Victor Burgin advises about photography and meanings: It seems to be extensively believed by photographers that meanings are to be found in the world much in the way that rabbits are found on downs, and that all that is required is the talent to spot them and the skill to shoot them...

In Fog/Ice (1985) [14], nature is usurping a covert activity. Who is the viewed and who is the viewer? The Irish Yeatsian swim is at work again in We shall never forsake the blue skies of Ulster for the grey mists of an Irish Republic (1986). Here again nature is the ironic equaliser. The viewing direction is looking southwards from the River Foyle, towards the Republic from a grey and misty Northern Ireland. But a good slogan does not worry about weather conditions. Doherty has continued this interest in the contradictions of place, territory and orientation in works such as West is South; East is North (1988) and The Walls (1987). He has also examined the historical processing of identity and nationalism in works such as Stone upon Stone (1986) and Lost Perspectives (1988). The use of text in these photoworks is direct and spare. They hang like movie subtitles in a kind of atavistic hold and must be experienced in a physical space rather than in book form. Their scale and serial presentation are set to work by physical encounter and contemplation. These particular images are in monochrome which seems appropriate to the enveloping nature of the conceptual charge. In 1988, Doherty turned to colour in responding to Paul Graham's photographs in Troubled Land. In Dreaming and Waiting (1988), he deals not only with the romance invested in the pictorialism of the landscape, but also with the process of myth-making and the journalistic travelogue feature. Doherty is on a journey that visits the same sites literally and metaphorically, time in and time out. Chris Coppock has observed; Doherty's work has been compared with the work of Richard Long and certainly on a formal level owes much to the preoccupations of Long and other exponents in the photo-image/text field. But this is where any similarity ends. Doherty's passion for Derry, a city steeped in contentious history, is of a fundamental nature. While Long scours the world, Doherty locates himself in an environment that he has known intimately from birth. The relationship of image to text is nourished by a highly subjective response, which channels modernist techniques in an attempt to articulate a personal localised polemic. In this sense, Willie Doherty's very particular vernacular perhaps offers a resistance to cultural travel. The form may be accessible but the dialect deceptive.7Since his audio/slide installation Same Difference (Matt's Gallery, London, 1990) to his recently acclaimed The Only Good One is a Dead One (originally Matt's Gallery, 1993) [24], the complexities of language mediated in the press and TV and the dangers of stereotyping as a barrier to understanding has compelled Doherty. He also explored the media role in the all too easy and immediate construction of innocence and guilt in the installation Six Irishmen. The dualities of perception, ideology and mediation, was developed in a different way in The Only Fool is a Dead One, for which he was shortlisted for the British Turner Prize in 1994. The Only Good One is a Dead One is a double screen, video projection installation. On one screen the artist uses a hand-held video camera to record a night time car journey, while the second screen shows the view from inside a car which is stationary on the street. The soundtrack is constructed in the interior monologue of a man who is vacillating hack and forth between the fear of being the victim and the fantasy of being an assassin.

The influence of various artists who have shown at the Orchard Gallery is clear. The central question is, does Doherty's work travel beyond the local? Is it too heavy a visual dialect to be understood elsewhere? The sensual intuition of subversion at work will be caught. Is that enough? Paul Seawright's photographic works are another example of the transformative power of text on image. During 1987/88, he made a series of fifteen photographs based on visits to the scenes of various sectarian murders, or the locations where bodies were dumped in the early l970s - an intense period of sectarian violence. He did not give the series a title, but reviewers have always referred to them as the Sectarian Murder series [26, 27]. The time interval of some fifteen years between murderous and creative act was important to the artist, not only to ensure the religious anonymity of each victim, but also, in a sense, to indicate that the murdered were victims of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Using an old diary from his youth, which noted significant political events among the fairly quotidian entries, Seawright spent protracted periods of time at these sites, considering the meanings associated with their location. In some cases, he re-enacted the route taken from the place from which a victim was snatched to the eventual spot of the murder or dumping of the body. Such reconstructions of reality built up tensions within the artist, as well as eliciting the lingering presence of gross transgressive acts from the location. Each scene was photographed in colour from the victim's viewpoint - close to the ground. The lighting of each scene was controlled, which paralleled the forensic photographer's cold, stark approach. These photographs, however, would remain merely interesting formalist studies if their accompanying text was not integral to their meanings. Seawright had researched original journalists' reports of these killings from local newspapers in Belfast, and selected snippets of text from such reports to work with and to discharge their related images of any easy reading. The text ties them down irrevocably to a place, a sub-culture and a value system of violence. In one work, a roadside inn is viewed, low down from the illuminated grassy edge of the road. A general feeling of tension is engendered by the angle of 'shooting', the absence of people, and the hiatus created between the nearside stationary car and the lorry about to pass the inn. Saturday, 16th June, 1973. The man was found lying in a ditch by a motorist at Corr's Corner, five miles from Belfast. He had been shot in the head while trying to hitch a lift home.

The blunt factual text tells of the killing of this misplaced victim. It also seems to indite the pictorial vehicles, as the location becomes perpetually marked and troubled. The essential difference between Paul Graham's photographs dealing with Northern Ireland, The Troubled Land (1987), and Paul Seawright's image and text photoworks, resides in the endorsement of lived experienced. As with TV coverage of such events, there is no reference to sectarian claims of justification or politicians' repudiations. The cold sparsity of the text, together with the concentrated absences in the photograph, unite to sustain a resounding moral condemnation of political cause and effect on both victim and violator. In his next series of photographs, Orange Order (1990-91) [28, 29], Seawright wanted to delve into aspects of his own Protestant background and culture. As a child, he had been taken to and enjoyed Orange marches. Now, as an adult, while he could still respond to them, he was aware of other perceptions as to their purpose and sense of ritual. He wanted to explore his own sense of unease. In these photographs, then, the older Seawright is still looking at the level of his younger self, but seeing differently. Like the Sectarian Murder series, these images are photographed from a low, probing angle, where gloved hands, legs, feet and sash-covered shoulders become the focus of an enquiry by stealth. He seeks out the Order's symbols of power and the power of corporate membership to recruit, initiate (the young) and sustain a demonstrative ideology. A working man may be dressed in his prescriptive dark suit and class-appropriated bowler hat, but Seawright spots his high-heeled, cowboy-style boots.

Colour contrasts are made to do much of the work. Emblematic details are isolated against dominant blacks. Even a black London-type taxi, usually anonymous throughout the year, is marked in red, white and blue for the day. Unlike the Sectarian Murder series however, text is avoided. In the latter series it was important that the ownership of the appropriate texts was not the artist's; rather they were reports of the time by others. The Orange Order series is without a generic title (again the naming of the series was by others), since constructing a title would point the viewer towards interpretation. Everything is entrusted to the power of the perambulating camera to open up meanings.

Words and text form a kind of material and moral land survey in Chris Wilson's work. Maps, territory, light intrusions, images of growth and decay, mark, measure and incubate the holy ground of Wilson's collages. These Gothic hothouse, abandoned interiors have atavistic taproots of deep penetration [see 31, 32]. Plantations, family ties and religion plot and piece Wilson's urban territorial map-making. Angela Kingston, in a recent catalogue essay, has commented: When he draws the bare earth, it is as though he is a farmer working a piece of land, attending to the matter at hand with a pleasurable respect. At each stage of his work, he seems to be striving to substantiate the ground he is working on - paper can seem so ephemeral - whilst at the same time gaining a practical knowledge of the fabric of the world.8Wilson's mapping technique is a measurement of transformation and acceptance. In his earlier sculpture, he explored substance as an idea. In Potato Table (1985), a table, or perhaps more accurately, a tabula is made of potatoes. A staple Irish diet, with its obvious socio-political references, becomes the material for what is usually an inanimate piece of furniture. This is not an eating table but something much more ritualistic. The use of reversals underpin a lot of his subsequent work. Harvest (1989) [32] brings back the potato as an offering from an absent congregation to an absent deity. With regard to this, Angela Kingston again says: There are memories, perhaps of churches and chapels overflowing with produce at harvest time, and packed congregations singing rousing hymns: does the spilling of potatoes in an empty, echoing church represent a moment of mournful longing for values, faith and community? Or was that dull thudding, as the sack was upturned, about futility and anger in the face of change?Wilson cites French poetry as an interest, with its searching for attachments. But John Hewitt, the Ulster poet, seems a more relevant association. Frank Ormsby points to Hewitt's restless fix as an Ulsterman: To be native to a province colonised by one's ancestors, at home and yet alien, a city man who loves, but must struggle to relate to, the country, someone aware of ... gaps that are finally unbridgeable, is to be perpetually unsure of one's place.10Derelict buildings also attract the English artist Tony Rickaby, who showed at the Orchard Gallery in 1983. This exhibition, The Powers That Be, continued his theme of buildings associated with state control or ideological control (the power of the Church) and the effects they have on peoples lives, this time in Ireland. The buildings here included Garda stations, courthouses, abbeys, castles and churches from the Leitrim/Roscommon/Sligo area. Rickaby made use of objects found in the vicinity of these buildings as symbols associated with the meanings invested in the building fabric. The drawings, as conceptual pieces [see 35], were much more successful than the paintings. They were physically made from reassembled pieces of paper found around the buildings, into which the artist had rubbed and etched words and phrases in Gaelic. The effect was to strike a parallel with the way meaning and association is encoded into the building surface. In The Oppressed and the Oppressor (1983), the drawing has a related rectangle of ceramic pieces on the floor. These objects were made of clay, squeezed by hand, fired and glazed black. They effectively conveyed, on the one hand, the frustration of the artist, and on the other, the manipulative power of Government and the Church. Another poet who, like Hewitt, is interested in painting is Howard Nemeroy. He sees a central connection in seeking after silence. He comments, 'Both poet and painter want to reach the silence behind the language, the silence within the language."' Joseph Kosuth actually obliterates language in some of his elegant silences. He deals often with the very slippery concept of translation, dealing with it in iconic terms. The interaction between words and spaces between words - that landmined terrain for engagement with translation - is neutralised by the artist. In works such as Zero & Not (1985) [36], the iconic possibilities are materialised again by an obliterating line. Conceptual art, once dematerialised, is rendered physical again as a new poetic object. Brian Friel, in a play such as Translations, demonstrates that what is lost in the act of translation can perhaps never be regained. And, since cultural identity is laid into the language, it is not surprising that language can become the cause of a violent interaction between the colonised and the coloniser. Seamus Deane, writing of Friel's play Translations, cautions: On the hither side of violence is Ireland as Paradise; on the nether side, Ireland as ruin. But since we live on the nether side we live in ruin and can only console ourselves with the desire for the paradise we briefly glimpse. The result is a discrepancy in our language; words are askew, they are out of line with fact. Violence has fantasy and wordiness as one of its most persistent after-effects.12Brian O'Doherty (Patrick Ireland) takes a related concept to translation, viz transcription. He transcribes abstract concepts in 3-D spatial rope drawings. He is fascinated by networks, structures, mazes and labyrinths. In 1985 he made Purgatory, a rope drawing, at the Douglas Hyde Gallery in Dublin, which was part of an ongoing series of rope drawings. The source for Purgatory was Joyce's Finnegans Wake - a series of non-sentences of line words. He takes these line words and traces them as a network over a section of the map of Dublin (the Irishtown/Phibsboro area). He takes this contrived grid and transposes it into a 3-D rope drawing within the gallery space. On a central axis to this grid there is a table and a chair. Spread on the table we have the opening sequence of Finnegans Wake written on blotting paper by hand. On either side of the installation, there are phrases being sounded out from speakers. Around the walls there is a series of ancillary drawings that indicate the thinking process behind the installation. He transposes ideas from one art form to another.

O'Doherty/Ireland believes in ambiguity and paradox. On entrance to the gallery, the viewer sees a projected series of letter forms on the back wall: HCE, which stands for the Earwicker theme, the Here Comes Everybody theme in Finnegans Wake. At first glance, the spectator thinks it is projected onto the back wall, but one later realises that it is painted onto the wall. More recently, he extended this interest in illusion, perception and ambiguity to the Ulster situation. Big H (1989) [30] dealt with an identity clash through the interaction of colour. Where the viewers stood would affect their perception of both the formal/colour interactions and the ideology at work. In contrast to Patrick Ireland, Rita Donagh, in the exhibition A Cellular Maze (1983) reacted to the idea of the physical and graphic presence of the H-Blocks on the landscape. She also considered the location of the H-Blocks in their proximity to Lough Neagh with its associations with ancient mythology. The artist also used the idea of the Six Counties as a territorial unit, or what she calls, the Shadow of Six Counties (a series of six works, 1973 onwards) [34] a shadow on the lung - the presence of the British? By exploring grids and various projections by way of a series of drawings, Donagh led one to Long Meadow [33]. Usually one sees aerial photographs of Long Kesh. Here we see the blocks diagonally set across the canvas like a still from a German expressionist film - light creates the intense mood of this air raid.

It can be seen that many artists who have responded to Ireland as a psychic landscape have deployed maps, networks and text. Sarat Maharaj, writing on Rita Donagh's use of the map, stresses that nothing ever is what it seems. Rita Donagh teases out and plays upon a particular feature of the map: the fact that if it gives us what we tend to take for granted as an accurate account of the world out there, it also looks radically unlike what it represents. In everyday, common sense terms we rarely think the two things in any way at odds with each other: the particular convention of representation involved has so much become second nature to us.13In Ireland, there is a particular relationship between words and image that is, in many ways, endemic to the culture. Witness, for example, the Government's banning of direct interviews with Sinn Fein representatives so that we get a curious form of image and dubbing. And, of course, there is the word, the text and the bible in Protestant fundamentalism, where truth is revealed in the word. By extension, there is a suspicion of the visual in that it may be 'wayward' and relate to fancifulness. There is also the literary structural models of writers like Joyce, O'Brien and Beckett. But what all the Irish artists considered in this section share is the use of words as ways of rinsing up what is invested in the cultural mapping of the psychic landscape. Of the four Ulster artists discussed who incorporate text into their work, it is Chris Wilson who uses the map as a 'text'. As an integral part of his imagery the map acts as an intrusive questioning device, plotting moral and territorial shifts. Text, in the form of his titles, assists Dermot Seymour in his use of irony and the priming of absurdities. Their convoluted, rolling, humorous structure extends the inflated and absurd meanings under scrutiny, against which we can appear puny and insignificant. Seymour's dumb animals (literally wordless) may look bewildered, but are called upon as important silent witnesses. He is also fond of using text by way of graffiti or military insignia as references to our society's prevalence for tribal markings and labelling. In Paul Seawright's Sectarian Murder series, texts and images are juxtaposed to form composite works . The cold, factual text in each case acts as a key to unlock the tensions in the already contaminated locations where sectarian killings were once carried our. On the other hand, Willie Doherty's photoworks text is used in the most directly penetrative way. Floated over an apparent photographic naturalism, they detonate meanings as if located within a shrapnel bomb.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||