Chapter 3 from 'Fourteen May Days' by Don Anderson (1994)[KEY_EVENTS] [Key_Issues] [Conflict_Background] UWC STRIKE: [Menu] [Reading] [Summary] [Background] [Chronology] [Sources] The following chapter has been contributed by the author, Don Anderson, with the permission of the publishers, Gill & Macmillan Ltd. The views expressed in this chapter do not necessarily reflect the views of the members of the CAIN Project. The CAIN Project would welcome other material which meets our guidelines for contributions.  This chapter is taken from the book:

This chapter is taken from the book:

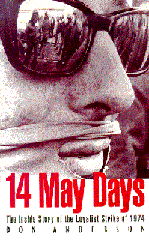

Fourteen May Days:

Published by:

Cover design by Identikit

This chapter is copyright Don Anderson 1994 and is included

on the CAIN site by permission of the author and the publisher. You may not edit, adapt,

or redistribute changed versions of this for other than your personal use

without the express written permission of the author or the publisher, Gill and Macmillan. Redistribution

for commercial purposes is not permitted.

CONTENTS

The UWC had surfaced just before the general election polling day to speak to Merlyn Rees, who was then shadow Northern Ireland Secretary. Harry Murray and UWC treasurer, Harry Patterson, were among those who told Rees that they would bring the province to a halt unless the Executive and the Sunningdale agreement were removed. The fact that the miners in Great Britain had succeeded in reducing electricity supplies sufficiently to force industry down to a three-day working week, and through that an election, gave the delegation added faith in the use of electricity as a political weapon. It was the UWC's first meeting with the man they were to confront three months later. Rees told them that the bipartisan policy would not be changed. The UWC was pregnant with threat but was having trouble with its dates. From 28 February the stoppage date was moved to 8 March, and then to 14 March. Billy Kelly, the power worker, was becoming angry with Murray because of the repeated delays and there was a heated exchange between the two men at a meeting in the Park Avenue Hotel in Belfast. Relations were almost at breaking point and Kelly considered going ahead himself using electricity as the sole weapon. He had convinced UUUC politicians by this time that he could have done it, but in the end he was unwilling to proceed without full backing. The spectre of the 1973 strike was always in the background. Murray's problem was one he never really solved but he believed he had to overcome it before any stoppage could begin. As he put it to me at the time: I still felt we weren't ready and I had to take a lot of abuse because we weren't ready. In Belfast I had prevented any publicity about the UWC. Some people were trying to keep LAW going. We didn't want to publicise that there was another organisation superseding it. We hadn't got agents in the ship-yard and in the different factories to spread the word. I wanted a little more publicity now on the organisation and its aims. I also wanted to get oil involved. I reckoned it was more important than electricity.That last point was interesting and not one Billy Kelly would have warmed to. Murray felt that he had the right to nominate the day, especially since he was paying the bills for the initial UWC meetings out of funds from a collection he was running in the Belfast shipyard. In Belfast the harbour estate enclosed several miles along the southern part of Belfast Lough and River Lagan. Within it lay the Harland and Wolff shipyard, which at the time was the largest single employer in the province; also the Shorts aircraft factory, another big employer-along with an airfield, some military installations, Belfast's gas manufacturing plant and an oil refinery. Murray was a shop steward in the shipyard and it was from there he set off one day in the middle of March to 'organise oil', as he put it. Note that oil had not been 'organised' for a strike even though several dates for a strike had passed by this time. The extraordinary manner in which Murray put various pieces together is illustrated in his description of that day. I started at the top of the road and I ended up four miles down the road, walking. I had just taken it into my head to go. I was on my knees, way past the Musgrave yard and the oil wharf. I didn't know what reception I would get but I happened to meet two blokes and I started talking to them. I got them to come along to a meeting at the Hawthornden Road headquarters a week before the stoppage.Revolutions happen in odd ways.

Part of the credit for instilling the idea in Murray's mind must

go to the Provisional IRA, who earlier in the year had hijacked

a naphtha tanker on its way from the refinery to the gasworks

in Londonderry. The tanker drivers retaliated by refusing to go

to the city until the IRA promised them free passage. In the meantime

Londonderry's diminishing gas supplies caused widespread concern

and Murray logged this in his mind until the day of his four-mile

walk.

There was more coherent movement among the Protestant paramilitary organisations. Every Wednesday night during April 1974, meetings were being held of up to thirty men representing all the paramilitary organisations on the Protestant side. The man who convened these meetings was Glen Barr, who was to become the chairman of the committee guiding the UWC stoppage. He was one of the new men thrown up by the Protestant body politic. Young, neatly groomed, energetic, plausible and fluent; one of the very few politicians who had managed to survive in politics while retaining a well-publicised connection with a paramilitary organisation, in this case the UDA. The Wednesday night meetings consisted of men from the UDA (Ulster Defence Association, the largest organisation), UVF (Ulster Volunteer Force), OV (Orange Volunteers), USCA (Ulster Special Constabulary Association), Red Hand Commando, UVSC (Ulster Volunteer Service Corps), DOW (Down Orange Welfare) and at later meetings, USC (Ulster Service Corps) which was found in Fermanagh and south Tyrone. The purpose of the meetings was to establish some form of political wing because it was known from experience that paramilitary candidates normally fared badly at the polls without one. At first the gatherings were indistinguishable from meetings of the Ulster Army Council, the 'high command' of the Protestant paramilitaries. However, they found it necessary to involve people who had political advice and skills to offer. This process had begun by the end of April. Coincidentally, the political parties, of the loyalist coalition, the UUUC, met at Portrush on 26 April to hammer out a combined policy document. They decided on a platform which included the continuation of a parliament for Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom, a more intensive offensive against the IRA based on locally recruited security forces and immediate elections to the assembly at Stormont. But interestingly, they shelved a decision on a general strike against Sunningdale. Back in Belfast, the Protestant paramilitaries used this document as the basis for their first political deliberations. Andy Tyrie, as commander of the UDA, was another of the key men at the centre of the stoppage. His plump unathletic appearance topped by glasses and a moustache disguised the ruthlessness and singlemindedness required to rise to the top of a large paramilitary organisation like the UDA, whose membership at the time was estimated at about 6,000. When Tyrie took over the position he reorganised by centralising control to a much greater degree and imposing tighter discipline. When he had accomplished this, he investigated the possibility of breathing new life into LAW because this organisation was effectively an arm of the UDA. The two shared the same offices. However, he faced two major difficulties. The first was that LAW would need rebuilding from the ground up, and secondly he knew that another Protestant worker organisation, destined to be the UWC, was beginning to emerge. In these circumstances he judged it would be easier to establish paramilitary influence in the new worker body. Tyrie believed the loyalist politicians, Paisley, Craig and West, to be rivals in this endeavour and that, unless he did something about it, the new workers' body would succumb to the influence of politicians. In his own words: The politicians always detested not being able to control LAW, so behind closed doors they tried to start another workers' organisation. They got in touch with certain people and invited them to their meetings, saying that if they were going to take over Northern Ireland they'd need to control certain things. So they got these men together, which flattered them, and decided on this workers' council.This was Tyrie's interpretation of the beginnings of the UWC and it probably led him to over-estimate the influence of the loyalist politicians within the UWC. However, the politicians were supporting Murray's caution about a starting date, saying that they would need to prepare the ground first. Also in the background was the fact that Tyrie had been angry with Craig ever since the February 1973 strike. Tyrie had understood Craig to have blamed the UDA for the debacle, saying that the UDA did not have the capability of backing a strike, a euphemism for frightening people from the workplace.

Nevertheless Tyrie was a practical man and was backing Craig and

the other loyalist leaders in seeking a delay in starting the

strike.

The meeting which finally decided the date for the stoppage took place at the beginning of May in the UDA headquarters in the Shankill area of Belfast. It was not a UWC decision. Tyrie was aware of the vacillation about dates and was sufficiently annoyed to tell the UWC group that their strike was not taking place until he said it could. He was also annoyed to discover that the worker organisation he aspired to take over was scarcely worth the trouble. Like Murray, Tyrie did not believe that cutting off electricity would in itself be sufficient to bring down the Executive. He believed, correctly, that the workforces of most other industries had not been prepared for a strike. It is a matter of conjecture whether Murray ever admitted to himself the logic of his position, which was that if he wanted a general strike he would be the prisoner of the paramilitaries because most workers would not leave the factories unless they were frightened away, or locked out because electrical supplies had been withdrawn completely. Both groups, workers and paramilitaries, believed the loyalist politicians of the UUUC were powerless and therefore did not invite them to the Shankill meeting. The paramilitaries invited the UWC people under the pretext of healing the rift with the rump of LAW. Tyrie had told Murray that if they were all going into battle then all differences should be healed in advance. Murray agreed and made sure that the members of the Belfast County Committee (in reality, the only part of the UWC that existed) turned up. When they arrived that night they could recognise only one member of LAW. 'Where are the phantoms?' Murray asked mockingly. Only then did it dawn upon him what the real purpose of the meeting might be. The men in that room represented every Protestant paramilitary grouping and their aim was to pin the workers to a definite course of action so that the paramilitaries could be ready on the day. Kelly was delighted at this turn of events but the paramilitaries were worried about the timing. Glen Barr was chairing the meeting and he was recommending that the strike call must be linked to an event. The strike needed a starting gun of some kind, if the metaphor is not too graphic. One suggestion was that the strike begin on the morning of 14 May to coincide with the continuation of a debate about the Sunningdale agreement in the assembly. Barr modified this to the vote at the end of the debate. The loyalists were bound to lose and a sense of defeat could be the trigger. Andy Tyrie still thought that decision was wrong and this remained his view even after the strike had been successful. Tyrie had been a shop floor worker in a Belfast foundry and knew something about industrial action. If you want to reduce opposition to a minimum, then begin your strike on a Monday when people generally don't want to go to work. I wanted the intention to strike declared after the assembly vote and the strike proper to begin the following Monday. This would have given us the rest of the week to get our propaganda going, to have electricity reduced enough to stop the factories even beginning to turn and altogether would have encouraged more workers not to go in of their own accord.Tyrie foresaw that a midweek start to the stoppage was going to give the UDA and other paramilitaries a lot of extra work. But even at this late stage Murray was half thinking of delaying action once more and gave this account of an exchange between himself and Billy Kelly, the electricity worker. Murray said to Kelly, 'What is the next date we could go on from a power station point of view, because the light is becoming too bright? It's just about right for me now because people wouldn't be in too much darkness from long nights.' 'You will not be able to go until October or November,' Kelly replied.

'That's all I want to know.' Kelly had finally convinced Murray

it was now or never. The paramilitaries were as happy as they

ever would be and the attitude of the UUUC politicians was of

little importance to him. There was just one question left. Would

the assembly actually move to a vote on 14 May? It was within

its powers to carry the debate over another day.

The Saturday before the stoppage the UWC met in the Vanguard Unionist headquarters at Hawthornden Road, which was in a pleasant middle-class residential part of Belfast, not far from Parliament Buildings at Stormont. This house was to become a well-known landmark as the headquarters of the UWC during the strike. There were about a dozen people present including, as Murray put it, 'Two old gentlemen from Omagh. I didn't know their names and they didn't represent anyone but they came to all the meetings. They carried messages back to a small association or a Vanguard-type organisation.' The Ulster Workers' Council was a grand title for a very small and informal ad hoc committee. The topic under discussion that Saturday evening was the public's evident lack of interest in plans for a strike. Few people believed such plans were serious and so it was decided that Murray, the press officer Jim Smyth and Billy Kelly should go over to the BBC studios in Belfast. Their aim was to create panic by advising housewives to store up food because there were going to be massive shortages and a power shutdown. The journalists in the BBC newsroom refused to listen to the relatively unknown group which suddenly and unannounced turned up on the doorstep promising chaos. The three men left threatening that when the stoppage happened, the BBC would receive no co-operation from the UWC. But the BBC was not the only quarter to disparage the strike call. On the evening before, Harry Patterson, Harry Murray and Hugh Petrie met a few of the loyalist politicians in a hotel in the loyalist stronghold of Larne. The Rev. Ian Paisley, John Taylor and Ernest Baird then learnt the full extent of what was being planned. It differed from the token stoppages politicians had in mind and they opposed the plan.

At the time John Laird, a senior member of Harry West's Unionists,

said, 'We still felt we hadn't pulled out all the political stops.

On the other hand we were politicians with responsibility and

no power and any politician who gets into that position is a twit.'

It was 14 May. The politicians and the stoppage leaders met again at Stormont. The UWC's Bob Pagels, Murray and Patterson arrived to watch the Sunningdale debate and to see if a vote was taken at the end of the day. At issue was a motion proposed by John Laird on behalf of the loyalist assemblymen. It read: 'That this assembly is of the opinion that the decision of the electorate of Northern Ireland at the polls on 28 February 1974 rejecting the Sunningdale agreement and the imposed constitutional settlement, requires re-negotiation of the constitutional arrangements and calls accordingly for such re-negotiation.' According to parliamentary practice, it is possible to propose an amendment which negates the original purpose and intention, so Brian Faulkner on behalf of the majority who supported the Executive, proposed this amendment: That this assembly welcome the declaration by the Executive that the successful implementation of its policy depends upon the delivery, in the letter and spirit, of commitments entered into by the British and Irish governments; calls upon those governments to fulfil such commitments; and expresses confidence that if these commitments are fulfilled, the system of broadly based government established under the Northern Ireland Constitution Act 1973 will enjoy the support of an overwhelming majority in the parliaments of the United Kingdom and of the people of Northern Ireland.The first main speaker was the deputy leader of the Vanguard Unionists, Ernest Baird. He outlined the threat. 'I have talked to some of these people, including Mr Harry Murray and Mr Billy Kelly, and I understand that they are saying that if those who are supporting this Executive -the Faulkner Unionists - persist in voting against the will of the people as expressed through the ballot box they will have no alternative but to bring industry to a halt.' He went on, . . .they have explained the situation in so far as a layman like myself can understand the intricacies of the power game in the sense of electricity. At the moment some 725 megawatts of electricity are going out all the time to the province. That is sufficient to keep going industry, essential services, the farmers and the housewives. About two-thirds of that electricity is used by what one might describe as the farming community, the hospitals, the drainage services and the housewives. Only one-third or less than a third is used in industry. That may be surprising but it is a fact. As I understand it, in the initial stages the men will be cutting down the power output to some 400 megawatts. That will give cuts all over the country but it is up to the Minister of Commerce to decide how this electricity is to be used.The ploy of convoluted logic can work. By the end of the strike a large proportion of Protestants were blaming the Executive for the damage. Baird's speech was an attempt to paper over the cracks between the position of the loyalist politicians and the UWC, cracks that were widening even as he was on his feet. Murray, Patterson and Pagels were watching from the public gallery even though they had not intended to. They left to try to find a cup of tea and ended up in the loyalist party rooms, where a heated exchange of views ensued. Murray recalled the episode. Most of the prominent loyalist politicians were there. Big Ian [Paisley] was on the telephone to the police about his security guard because it had just been taken from him. And Bill Craig, whose house had just been bombed, had lost his security guard. This is what was in their minds. It was typical of them. The three of us were worried they seemed to have no will to win. We told them they were bankrupt of ideas and were finished as far as leading the people was concerned. I said the people were leaderless and none of them knew which way to turn.The row damaged their morale. If the strike did indeed fail, the loyalist politicians would not protect them. Privately the politicians were opposing them. Murray was depressed. The roof could have fallen in on me. I turned to Craig and asked if there was anything they could do. He said there was not and that the strike would be a failure. I looked all around at them - Ardill, Baird, Craig and Paisley - and none of them would even make a move with his lips. It was coming up to ten to six and Paisley wanted West to carry on [speaking in the debating chamber] over the time so that there would be no vote that day. This would mean a fortnight or three weeks before another vote. When he [Paisley] put that to me I told him it wasn't on. It was now or never.But an account from a politician who was present states that the three UWC men were under pressure that afternoon and at about half past five they panicked. He said the workers were the men who wanted the debate continued because they were not ready. It was the politicians who said that the die had been cast and that UWC men would have to be satisfied with what- ever had been arranged for the stoppage. Just before six o'clock the Northern Ireland assembly divided for the first time in its short history, and as it would transpire, its only time. The loyalists lost by twenty-eight votes to forty-four. In a corridor a BBC journalist found Harry Murray alone and told him the news of the vote, pressing him to come to a nearby television studio. Murray wanted to have Bob Pagels and Harry Patterson confirm the figures but the television programme was on air and could not wait. He had to decide himself. He turned and went into the studio.

On the morning of Wednesday 15 May the response to the strike call was poor. An overwhelming majority of the workforce turned up for work. 'It wasn't organised,' Harry Murray said afterwards. 'The people weren't educated.' Murray thought his own wife was joking that morning when she asked him why he was not at work. Nor did Bob Pagels' wife take him seriously, at least not until she went into the kitchen of her Belfast home to make breakfast to find there was no electricity. She thought a fuse had blown. When the truth dawned she felt the same as most. 'What on earth are we striking for? Do we need all this?' At Stormont the stoppage was not foremost in the minds of the Executive. Its members were pleased to have reached the end of the Sunningdale debate the previous evening. For weeks the vote had been delayed by what amounted to a filibuster by the UUUC parties and the debates had been dreary and repetitive. For the UUUC there had been advantage in having the loyalist viewpoint reported in newspapers, radio and television at some length. The Executive regarded the end of the debate as the passing of an obstacle rather than the approach of one and paid as little attention to the strike call as the rest of the province. The Harland and Wolff shipyard was a good indicator of what was happening within the Protestant urban communities. On the first morning of the stoppage a very large number was at work - this at the very place where Harry Murray was a shop steward. The problem was not simply a lack of enthusiasm; many workers were plainly opposed to the stoppage. Support for the stoppage in the shipyard was largely confined to a couple of hundred stagers in the shipyard. These were the men who erected scaffolding or staging round a ship under construction and as a group had the reputation of being hardliners. A meeting was called for ten o'clock in the morning at the head of the large building dock. Consistent with the feeling in the yard it was sparsely attended and adjourned as a flop. The organisers called another meeting for lunchtime but this time the stagers went round the buildings and plants drumming up support and there was a larger attendance at the second meeting. Those against the strike did not have much opportunity to vote against it. The mot- ion put to the workers was whether or not they were against the Sunningdale agreement and in a mainly Protestant workforce the outcome was predictable. 'That's it. You're out,' said the platform. There were some ineffective protests at this from the floor before the meeting broke up. The workers were still slow to leave the shipyard but were hastened on their way by rumours that the shipyard was the only large concern still working, or that workers' cars still parked in the yard after a certain time would be burnt or that paramilitaries were already putting up barricades cutting men off from their homes. Small wonder that the bulk of the workforce left after lunch, though some held out and were still at work at half past three that afternoon. One such man was Sandy Scott, the chief shop steward, who was very much against the stoppage at the beginning, though, like so many others, he was to change his mind in the light of Northern Ireland Office attitudes. It had crossed his mind to try to counter what was going on. I didn't go to the meeting at lunchtime because I realised that the muscle boys were going to put the pressure on. I've no doubt that the general feeling inside was against the strike but I knew that back in the ghettos it would be a different matter. They would give way under pressure. The barricades would go up and they would not be able to get out.That is precisely what happened. Bob Pagels had at least organised within the animal feedstuff mill in which he worked and only a few men turned up for work on Wednesday morning. In common with much of Northern Ireland the mill management was confused. Pagels was supposed to be at work at six o'clock in the morning. At seven the mill management telephoned him to find out what was happening and he went down to the mill to explain. On the way he saw cars parked round one of Belfast's big engineering works, Sirocco, and wondered why. This was the plant where the Jim Mcllwaine, secretary of the Belfast County UWC, worked. Surely it could not be working - but quite evidently it was. Pagels entered and met a nonplussed Jim Mcllwaine wearing his non-working good clothes who told him that the Sirocco workers did not want to strike. 'I must have a wee talk with them,' Pagels said. 'They'll have to fall into line.' Pagels went onto the shop floor, wearing a coat and a pair of sunglasses. He walked through the lines of machines shaking his fist. The image was enough. Large numbers of workers left soon after. In microcosm, that was the story of the first few days, a story of massive intimidation. The most effective shutdown was in the port of Larne, a ferry terminal about twenty-three miles from Belfast. Larne was very largely Protestant and from the beginning was controlled by Protestant paramilitaries. Nearly every business in the town closed on the first day; men in combat jackets carrying clubs ensured that shops shut; the harbour area was sealed off with a barricade of two cars and a container lorry. In fact, Larne was shut down so tightly that some of the organisers of the stop- page at the Hawthornden Road headquarters were complaining about the inconvenience. Larne was an important port but it also controlled the approach to the biggest power station feeding the Northern Ireland grid. The situation in Larne therefore gave the paramilitaries an inde- pendent capacity to reduce electricity supplies without reference to the UWC power workers or their leader, Billy Kelly. Later in the day the police cleared the barricade blocking the single road to the port but by that time British Rail, which operated the route to Stranraer in Scotland, had cancelled the service until further notice. The early morning ferry which had already left Scotland was ordered back to Stranraer. Meanwhile other big factories outside Belfast were coming to a halt. At the ICI fibre plant near Carrickfergus, halfway between Larne and Belfast, 1.500 men walked out. This was the first blow to the man-made fibre industry which was well established in the province. The sector was more sensitive than most to labour trouble or power failure because the plants involved a continuous process. They needed to be kept running or be shut down in a controlled fashion to prevent molten plastic gumming up the works. In other towns, such as Portadown which like Carrickfergus and Larne had a majority Protestant population, the strike began to take hold. The way the stoppage began was much the same. Workers turned up because nothing had been organised to the contrary. A mass meeting was then held called by activists for the purpose of supporting the Protestant cause. At this point the dividing line between intimidation and legitimate communal pressure becomes difficult to draw. The UWC was a failure right from the outset. It had failed to establish even an elementary form of framework for something as ambitious as a general strike and therefore never had a chance of convincing and persuading workers to strike. The UWC's only success was in the power stations where the levels of electrical supply were reduced to sixty per cent by lunch- time on the first day. However, workers sent home from the factories because there was no power or because they were frightened were involved in a lock-out, not a strike. The UWC was prepared to gamble on a mass lock-out based on the withdrawal first of electricity, then oil. Harry Murray was explicit when he talked to the paramilitaries at the Shankill Road meeting shortly before the stoppage began. He had said, 'It's either civil war or passive resistance, pulling electricity and petrol right down, if the response on the second night had not been what it was. I didn't care who went to work. We were deter- mined, the four of us.' The four of us. The paramilitaries saw through the UWC claims. Glen Barr and Andy Tyrie did not believe that the UWC had enough strength to organise in the power stations and at one point told Billy Kelly and his colleague, Jack Scott, that their claims to have planned in the power stations for eighteen months was a load of rubbish (putting it politely). Strangely the paramilitaries were more sensitive to the need for political considerations to be taken into account. The less preparation, the more the paramilitaries would need to intimidate, but the lesson of the February 1973 strike had been learnt by the paramilitaries in greater depth than by the UWC activists. Immediately before the strike Andy Tyrie gathered the brigade staff of the UDA and told them that the workers had no idea of how little support they had. 'It's going to be up to us to do the dirty work again,' he told them. 'But we are going to have to make sure there is no violence this time. If there is any violence then everybody is going to back away.' Non-violence is not a prominent characteristic of paramilitary organisations and Tyrie had to argue his case long and hard. (It should be noted that, in the UDA, intimidation was held to be non-violence.) He said that if they did not bring about the down- fall of the Executive on this occasion, the failure would put the loyalists back four years, which was how long Tyrie believed it would take to regain the confidence of the ordinary Protestant. It might be worse, he had said, for at the end of four years the loyalists might have already lost. A failed strike would bolster the Executive. This meeting of UDA leaders was important. When the 'brigadiers' agreed on a strategy and showed themselves capable of carrying it out, this had a bearing on the response by the army, the police and the politicians in power. In Tyrie's view intimidation (he called it 'discouragement') had to succeed in the first few days of the stoppage. So the UDA, the UVF and other members of the Ulster Army Council mounted their campaign to close factories from lunchtime on Wednesday, when they issued a statement ordering all loyalists to cease work forthwith. An Army Council statement read, 'Ulster Army Council personnel and pickets will receive directives to permit essential services to persist. These will be given over the communications media. All other movement will cease.' This action continued on Thursday and Friday, by which time they considered the job almost finished. Note the assumption that the directives could be relied upon to be passed on by the media, a subject which I will return to.

But the statement had another effect. It demolished the fiction

that the stoppage was a spontaneous or planned worker action.

It demonstrated that the UWC had become the creature of the Protestant

paramilitaries. The UWC men and representatives of the paramilitaries

met publicly at the Hawthornden Road head- quarters for the first

time as a co-ordinating committee. It was a large and cumbrous

body of sixty which proved so unwieldy that a small 15-man committee

was set up after the first weekend.

|

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||