'Burntollet' by Bowes Egan and Vincent McCormack[Key_Events] Key_Issues] [Conflict_Background] PD MARCH: [Menu] [Reading] [Summary] [Background] [Chronology] ['Burntollet'] [Sources] Text: Bowes Egan and Vincent McCormack ... Page Compiled: Fionnuala McKenna

'Next time, it will be the last rites WHILE the marchers waited and parleyed outside Cumber Church, a few individuals not hitherto known for their support of the Civil Rights movement hovered round. Moving between the demonstrators and police, now chatting with Constable Nigel Robinson, now listening to police advice and hearing reactions from the marchers, was Derek Eakin, a garage-man who lives in Claudy. Samuel Leslie, last seen on the outskirts of the village had now overtaken the walkers. and half-a-dozen others, noted for their vocal opposition to the march stood, watching and listening. Eventually, the march started, and swung left into the straight road that reaches Derry seven miles further on, with Leslie, Eakin and his companions, and the other hostile people still standing round the crossroads. The official procession order began with some police vehicles. Then came a district inspector out in front, alone and twirling his blackthorn stick, then, about thirty feet behind, there followed some dozens of the riot-equipped police. After that came the marchers about five hundred in number, and finally more tenders with police. But an unscheduled group of performers stole the lead. Eight yards or so in advance of the district inspector scampered seven young men. These were of the group already implicated in the attack on the pressmen's car. One of the boys was twirling a Union Jack on a pole, three others trailed a football supporter's coloured scarf between them, the rest just capered along, all shouting slogans and singing snatches of their loyal songs. "The repeated refrain 'up to our knees in Fenian blood' seemed a little ominous to me," wrote Eddie Toman in his subsequent description. To the left-hand side the adjoining field dropped to join the shallow River Faughan about a hundred yards away. The right-hand side rose with greater sharpness, but a hedge of varying height set on the bank obscured full view of the higher ground. Taking police advice, the marchers hugged this side of the road, hoping to minimise the likelihood of being struck by stones. But equally this blocked the demonstrators' view of what was happening abreast of them in the fields, and on the road ahead. The hedgeway broke once for the tidy garden of a cottage, once to expose the frontage of a bigger dwelling place where a small group of people waved flags and shouted slogans and abuse. Three hundred yards passed, the danger spot as indicated by the police was now behind. Another hundred yards were covered, but glimpses of the higher ground showed only a squad of police moving parallel and slightly in advance of the procession. Yet this protection made one marcher, Joe Quigley, feel uneasy. "I wondered why the men going along the high ground, and sent, as we might suppose, to discourage or apprehend stone throwers, were dressed in ordinary uniform with no protective additions. Yet those accompanying us on the road were most elaborately protected. And despite all their protections they seemed extremely apprehensive. It seemed to me that they had some reason to believe their unprotected fellows were not going to succeed in clearing the throwers."

The capers of the fellows to the front continued. Their behaviour might have been calculated merely to ridicule the march and to make the peaceful demonstrators angry or embarrassed. But their loud calls, and the prominent waving flag, gave clear notice of how the march progressed to any ambushers who lay in wait. The amateur efforts of this group were soon effectively supplemented; a lone man stood in the higher field about fifteen feet back from the road. He was wearing a white armband and making elaborate arm signals. The police in the field, under the direction of Chief Constable Kerr Patterson, approached him, came abreast, and passed. One marcher, wondering that a force sent to usher possible attackers from the roadside should ignore a man so clearly bent on a purpose connected with the demonstration, concluded that this must have been a plain-clothes policeman. In fact, he was Noel Leslie, who lives in the main street of Claudy village. The march continued slowly along the road, the walkers catching glimpses of the higher ground and police detachments through irregularities in the hedge. The next field disclosed about fifty people standing around in groups. Of these, Chief Constable Patterson and his policemen, came first in contact with a group of sturdy young men. Each of them carried a cudgel or some other weapon. The conversation between the groups seemed to be of quite an amiable sort; the young men moved casually ahead, now walking parallel, and a little in advance of the march, each one still fully armed. The policemen remained slightly behind them. In the centre of this group was Sammy Cooke. The others were three brothers, David, Noel and Andy Moore, and Cecil Miller. Most of these men are workmates in William Leslie's quarry at Legahurry, a mile away from where they stood.

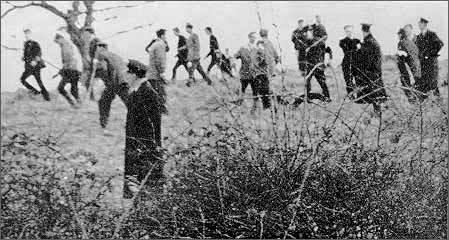

A group of attackers wait for the marchers to appear. . . The junction of the next two fields is obscured by an overgrown trough area surrounded by trees. A very young girl, perhaps fourteen or fifteen, appeared, jumping up and down and screaming, "Paisley, Paisley, Paisley." Then the bombardment really started. Bottles, bricks and stones rained down. One marcher noted: "I am not speaking of chips or pebbles. These were quarried stones, some of them several pounds in weight." His assessment was good. The field past the trough ran beside the road for more than a quarter of a mile. At approximately eight-foot intervals just behind the hedge, and at rather longer intervals further back on the higher ground, heaps of newly-quarried stones had been deposited. "These certainly could not be found anywhere on the land," the owner, Tony Gormley, tells, "and nothing of the sort was there on the evening of January 3rd." The use of these stones is well illustrated by John Gilmore, another Belfast student: "I saw people, including one man who was standing with an armful of stones against his chest on the lower ground to the left of the field. Suddenly, I heard screams coming from behind, and looking around saw a shower of stones in the air. The march scattered in some panic; then I saw a girl being put onto a police tender with blood pouring from her head. Then I saw a television cameraman with blood streaming down his face."Because the attackers moved onwards with the march, some piles of stones further back from the road were virtually untouched. From these, and from the sacks left round, and from several full sack-loads found at another point nearby, it seems that between seventy and ninety hundredweights of stones were brought to Burntollet and deposited there during the night. To distribute these would have taken one man about six hours. The greater part of the work was achieved by a group between four and six o'clock in the morning; yet the patrolling police, according to the Minister of Home Affairs, have "no information as to stones being brought to fields adjacent to Burntollet from elsewhere."

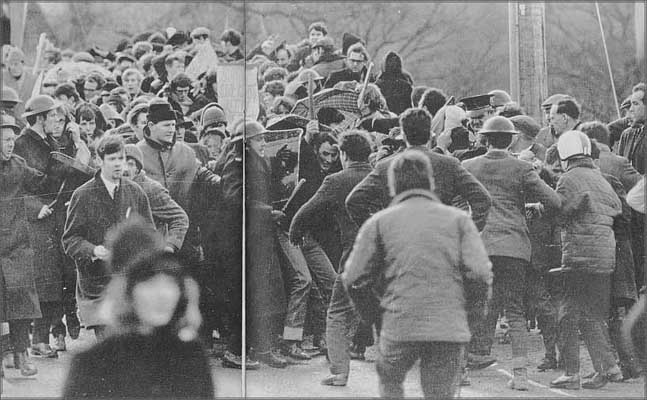

Into action . . . attackers, unhindered by the police, race to cut off the marchers. To make use of this ambitious armoury, about a hundred and fifty people had been recruited to the field. They were mostly local people and included a sizeable proportion of the female population of Gulf Cottages, Killaloo. As Chief Constable Patterson and his men tardily arrived on the scene, they moved some throwers onwards, and again the body of attackers and the police progressed in the same direction, parallel with the march. Several photographs show one particular incident where a number of policemen are held in conversation with a stout, unbudging figure in the centre of the field. This was Samuel Evans, substantial farmer of Goshaden, who watched the attack develop with the satisfaction of a triumphant general. And in this field, from where the fusillage was being directed, now reappeared Derek Eakin, the man who had been left behind by the march at Cumber Church. With him was William Boreland, a car salesman of Dungiven. Both wore identifying white bands on their left arms. Not far off stood David Simpson; this man comes from Moneymore, a town twenty-five miles away. But apparently he had learned in advance of the exact location of the attack, and played a full and vigorous part, showering stones among the marchers. According to good evidence he held a branch of a tree, fashioned as a club, in one hand. At this stage, a number of walkers sought escape through a gap in the hedgeway, and moved into the field to mingle with throwers. There were shouts from the attackers as they saw that the newcomers wore no white armbands. And Chief Constable Patterson's policemen descended, batons drawn, to drive them from the field, back into the main injury area. "I have no doubt at all," says one of these men "that the police in that field were there not to protect the marchers from the stoning which they must have known all about in advance, but to protect the attackers from any possible retaliation." Another local man survived the first shower of stones and tells: "As we came near the Bridge the police were herding a few stragglers across the field. I recognised a man called Cooke from the Killaloo district. He was holding a large stone or brick in his left hand. I heard a cry of 'get the bastards', and stones and bottles rained down."The large field where the throwers were situated tapers to an end where a small laneway meets the main road at a sharp angle. Concealed from the marchers up this pathway were more than sixty men armed with cudgels, crowbars, iron bars, lead piping, and much more elaborate instruments of chastisement. Almost opposite the concealed junction of Scribetree Lane and the Derry Road is another side road leading towards Ardmore. Here a second well-armed contingent of attackers stood waiting in fullest view of all who passed along the road. They had prepared piles of stones quite openly along the roadside, and these they hurled at the approaching marchers. Central in this group were John Haslett, a garage owner of Claudy, and Lloyd Cooke, of Legahurry cottages. Both men played a vigorous part in the attack. As the riot-clad police at the head of the march came to the road junction, ambushers emerged from both sides. From the Scribetree Lane side came Ronald Bunting, with John Cooke, William Cooke, William McGuinnes, Ronald McBeth, Willy McBrine, Billy McClelland, Cecil Black and a crowd of other men, some local, a few brought by Bunting, and a number apparently recruited through the special constabulary from areas as far as thirty miles away. After a slight show of resistance, the police pushed onwards and some of the front ranks of the march followed. But, by the very nature of the police phalanx which offered protection to front and left, the majority of the marchers were delivered precisely into the hands of the group up Scribetree Lane. A clear description of the sequence of events appeared in the Irish News. "The major portion of the C.R. procession was cut off and left at the mercy of the attackers. A fusillade of stones and bottles was followed by the full weight of the attack against the young men and women who had pledged themselves to a policy of non-violence.

Ambushers surround a group of marchers. A cannonball-size boulder

on the road gives The demeanour of these men as they rushed out had particular significance. As one marcher puts it: ". . . in a determined and quite unhesitant way, as though they knew beyond doubt the marchers were quite determined on a policy of non-violence and they also knew beyond doubt that no one would challenge their right to mete out punishment."Recapitulating, one of the marchers, a school teacher, gives his account of the attack: "I saw the police moving through the fields, and then I saw the first attacker wearing a white armband. Then I began to see other men wearing similar armbands standing in groups on high ground along the road. I remember then dismissing the idea that the attackers would simply be angry groups of locals annoyed at demonstrators passing through their village. My impression now was that the attack was well organised, and the armbands were for recognition purposes.

By the very nature of the police phalanx, which offered protection

to front and left, the One local man who joined the march at Claudy told that "two men with clubs I recognised . . . one was called McGuinness, of Gulf Cottages, Killaloo." Another marcher, Cohn Moore of Belfast describes a single incident: "I then saw a girl with a white, furry hat being confronted by a Paisleyite with a wooden club. The hat was taken off and she received two blows each followed by blood."Mrs. Judith McGuffin, a schoolteacher from Belfast was more closely and personally involved: "Showers of rocks crashed round us. I was in the middle of the fourth row and bent double in an attempt to avoid the hail of missiles, when a middle-aged man in a tweed coat, brandishing what seemed to be a chair leg dashed from the left-hand side of the road, hit me on the back, then pulled down the hood of my anorak and struck me on the head. I then tried to crawl away, but, teeth bared, he hit me again on the spot on my skull . . . I fell, and a fellow marcher picked me up and dragged me up the road; I passed out, and came round in the ambulance on the way to Alnagelvin Hospital."Judith McGuffin's husband, John, gives his own account: "I saw some policemen in a field on the high ground herd a small number of people with rocks and sticks towards the bridge. They made no attempt to disarm anyone. The next thing I know was that some large rocks were hurled into the march. We crouched low and tried to protect ourselves with coats and hoods. A horde of people appeared, armed with iron bars, clubs and bottles. Many were wearing white armbands and helmets. Six men with clubs jumped out from the right and began, indiscriminately, to club people round me as I bent low to avoid the rain of missiles. We ran through; I was struck four times on the head and several times on the shoulders, and only my heavy coat saved me from injury. Being to the front of the march, I was fortunate enough to get through but, turning round, I saw that the main body of the march was cut off. Running back thirty yards I found my wife in great distress, and bleeding profusely."

A group of ambushers coming from the Ardmore road openly attacks

the front At this stage the group of young men who had led the march, flying the Union Jack, put their energy to more than symbolic use. Thomas John Brolly, of Faughan View Crescent, carried the emblem on a substantial pole. Constable G. French has given evidence that he saw Brolly strike a girl on the back of the shoulders and the neck with a stick. Both Brolly, and a colleague of his, Ronald CaIdwell of Donemana, were subsequently fined for disorderly behaviour. Brolly was also found guilty of assaulting the unidentified female victim. And on the bridge occured a series of incidents among the most grotesque in the entire attack. Mrs. Margaret Tracey, a fifty-four year-old housewife, of Dungiven, gives her account: "I passed through the hail of stones, being hit only once on the leg. When we crossed the bridge I turned back because my three sons were in the march, and I wanted to find them. Standing on the side of the bridge to the marchers' left, was a large, middle-aged, well dressed man, leaning against the bridge wall quite casually. As a line of marchers passed he whipped what seemed like a police baton out of his overcoat pocket and smashed it on the back of the nearest marcher. Boys and girls went down, one after another."This story is well backed by the accounts of other witnesses from the march who were called by Mrs. Tracey to watch and act, but their appeals to the police were of no avail. They were either attacked immediately by the constables, or threatened. James O'Kane, also from Dungiven, is a possible recipient of this well-dressed attacker's attentions. "I was half way across the bridge, walking on the extreme left-hand side of the march, when I was struck from behind on the head with a baton or an iron bar. I was badly stunned and fell, but I fought to stay conscious because I was afraid of what would happen, I staggered over against the parapet of the bridge. I was bleeding badly."

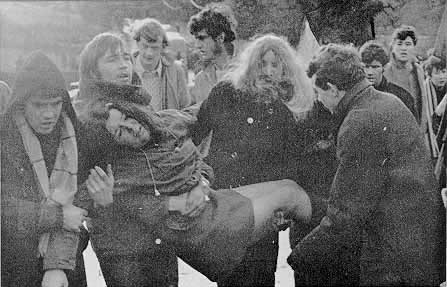

ABOVE: A girl marcher, obviously in pain, is carried out of the "firing line" by fellow marchers. A number of girls were savagely beaten in the attack.

Describing the activities of this same gentleman, William McConigle, of Dungiven, recounts: "There was a man with a baton on the bridge. He went to hit me by swinging the baton. I side-stepped, and another man hit me with a nailed stick on the back of the head. I saw the man with the baton hit other people, girls and men both."This attacker was Geddis Fulton, a substantial farmer of Camnish Dungiven. By this time a number of overloaded ambulances were carrying the injured towards Alnagelvin Hospital in Derry. One injured marcher tells how he was carried into one of these vehicles then: "About fifty yards ahead a group of men armed with sticks and bars formed a road block. One carried a hatchet, another a billhook. For a few minutes it seemed that they were going to drag us from the ambulance. But then the leader contented himself by saying, you got a lot less than you deserved. Next time we see you, it will be the last rites, as you call them, that you'll need. We'll kill each last one of you that turns up in this area again'."

|

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||