'Burntollet' by Bowes Egan and Vincent McCormack[Key_Events] Key_Issues] [Conflict_Background] PD MARCH: [Menu] [Reading] [Summary] [Background] [Chronology] ['Burntollet'] [Sources] Text: Bowes Egan and Vincent McCormack ... Page Compiled: Fionnuala McKenna

Running the gauntlet in Irish St. and Spencer Rd. FRANK Elliot, who lives in Strabane, more than fourteen miles from Derry, drove to the city on Saturday morning to watch the Civil Rights march arrive. Having parked his car, he moved towards the area through which he expected the procession would come. He recalls: "At the junction of Duke Street and Spencer Road, I saw about thirty youths marching, armed with everything short of firearms. Police, who were nearby in good numbers, disarmed some of them, but the majority of the police did nothing. I watched one policeman approach a youth and take a lot of stones from him, and then let him go without taking his name. So I approached and was told, with accompanying obscenities, to mind my own business. I told him that I would see more about this and again was treated to foul-mouthed abuse."This story has a curious sequel. Elliot noted the offending policeman's number and approached a senior officer. No help was offered. So he went to the central city police station to make a report. The policeman on duty, whose number Elliot noted, became furious, refused to take note of his complaint, and ordered him to leave the station. He returned, accompanied by a number of witnesses. With obvious reluctance, the duty officer accepted a written note of his complaint. Elliot later repeated his account for the benefit of the senior officer appointed to make enquiry into police conduct around that time. No attempt was made to take any statement from him, and he has not been visited by any officers conducting enquiries. In answer to parliamentary query, Home Affairs Minister Porter explained first, that the constable identified had not been on duty; secondly, that the complaint had been fully dealt with before Elliot lodged his formal statement, and finally that no formal acknowledgement was sent in response to oral complaints. The internal defects in the sequence of ministerial answers could scarcely be more glaring and ludicrous. If the policeman who corresponds to the number cited by Elliot was not on duty, then it comes close to impossibility for the senior officer to establish the facts before returning to the station. The Minister did not care to tell the outcome of the enquiry he so cheerfully cited. And, as has been mentioned, Elliot's statement was in writing, drawn up and signed by himself. It would seem that the Minister has been misled about the nature of the statement, and it is not unreasonable to assume that his information is based on the present content of police files in Victoria Barracks. Frank Elliot's account of armaments carried openly by hostile crowds in the city streets, and in full view of the police, is well authenticated by statements and by photographs. Another observer, in the same area, told of men boldly carrying buckets full of stones.

Attackers near Irish Street pelt stones at marchers while police walk by, apparently neither hearing nor seeing anything to prompt them into action to protect the marchers. Some attackers rushed down and beat the marchers with clubs. Behind the houses and shops that make up the left-hand side of Spencer Road as one approaches the city, a steep escarpment rises. In past years this had been a quarry, used for supply of materials to building sites. It had fallen into disuse, but at the time the march was due to pass through, a public concrete stairway up the escarpment face was being constructed. This meant that, in addition to the stones already available, larger white rocks had been brought in as foundation and surrounds for the concrete steps. For years one of the amusements of the youth of Derry has been throwing stones down this escarpment towards, into, and indeed right over Spencer Road. One man who lives above this area reports: "A good two hours before the march was due to pass, I saw some young men dumping bottles at the escarpment top. I knew the student march was due to pass right below, and I also knew how easy it would be to throw quite heavy stones over the tops of the houses and on to the road.The marchers had quite a few more hazards to encounter before they felt the missiles drop into Spencer Road. A few hundred yards before the boundaries of Derry they were stoned by a group of about fifty people led by a stout, middle-aged lady. The police did not try to interfere; no arrests or identifications were made. Then the walkers reached the part of road that borders on the large Irish Street housing estate. Just eight feet up a grassy bank is an open, level space. Set at varying distances back from the road, are the hundreds of houses of this large settlement. The bank was crowded by groups of assailants, armed with sticks and bottles. Once again, well-prepared piles of stones were in clear evidence. Missiles showered on the marchers, and detachments of attackers rushed quite openly down and beat the passers-by with clubs. A reporter from a Belfast newspaper wrote on January 6th: "A People's Democracy marcher fell like a log at my feet, when a stone, bigger than a man's fist, smashed on his head and blood poured down the side of his face.While sympathising with the reporter's shattered faith in soft femininity, his description cannot wholly be commended. The stone throwers were not children. Photographs of a most revealing sort show that they were mainly well-grown men centred round a number of Union Jacks set as a rallying point on the green. Picture after picture shows readily-recognisable individuals holding and hurling missiles. And, in many cases, a stone thrower is near compliant policemen. The identity of these vigorous ringleaders is most intriguing. They are the original Burntollet attackers, the same old gang. As the fracas there died down, a cortege of more than forty cars, carefully parked on the Ballyarton and Ardmore roads above Burntollet, set out along a back route to Irish Street, and arrived in time to lead another attack. Thomas McErlean, of the People's Democracy, describes his memory of the entry into Derry: "Once again, a number of young people carrying Union Jacks led the march into Irish Street. There were one or two police tenders in front. I saw the crowds on either side of the road, and I could also see heaps of stone, glass and rubble. Before these started flying, a woman threw a bottle filled with liquid at me. This splashed over my face and hands. Someone beside me shouted that it must be acid, so I tried to rub it off. It was not till the rain started later that I felt the taste coming into my mouth, then I knew it must be a petrol bomb."A number of marchers describe an incident here recalled by Micky McGonigle, of Dungiven: "I saw a farmer from Dungiven kicking a woman who was in the march. The police were immediately given his name by a number of us who knew him. Immediately, they drew their batons to attack us. The man was Thomas Fulton."This incident, also, had a curious sequel. Next night a barn belonging to Fulton was burned down. He made a claim against the County Council, saying that the cause was malicious injury for which local authorities accept financial responsibility. To substantiate his argument that people were sufficiently incensed against him to take such incendiary measures, he explained the situation in terms later recited by a council official: he had "taken part in the Burntollet parade." Another newspaper report of the Irish Street attack tells how: "Some of the people on the grass swept down to attack the marchers, and one student of about eighteen years of age ran back up the road. He was followed by a group of people, and was being struck, when he was rescued by a prominent Londonderry Unionist, the Rev. John Brown, President of the North Ward Unionist Association and County Grand Master of Antrim Grand Orange Lodge."The fortuitous appearance of the Rev. John Brown afforded this charitable clergyman a practical view of a subject in which he has intense academic interest. As lecturer in history at Magee University College, he has written in detail about the development of the Orange Order, concentrating on its practice of harassing demonstrators, from the time of Daniel O'Connell's Catholic Emancipation Movement onwards. Burntollet and Irish Street fall well within the tradition of ambush and attack he so ably describes, and the injured youth was certainly fortunate to find a protector who could speak to his attackers not only with an authority of a Chaplain of the Orange Order, but also in his capacity as Sub-District Commandant of the Border and District Special Constabulary. Once more, marchers and observers had nothing complimentary to say about the police. Peter Cosgrove, who had clear view of the prepared piles of stones, recounts: "If I could see these stones quite clearly in all the confusion, we can be quite certain that police patrolling the roads were at least equally aware that attack was imminent. And I suppose they must have seen the piles actually being deposited. Initially, they made no attempt whatever to stop the stone throwers but, protective riot shields covering their right-hand sides, literally fled down the road leaving the marchers vulnerable."Seamus Murphy describes how, "at Irish Street we were met with an avalanche of stones, sticks, and petrol bombs. The police, like good guardians of law and order, immediately got into their tenders and disappeared." These descriptions sound harsh and hard to justify. Yet a single photograph, blown up in detail, shows a group of five policemen walking along the road. Along the side, not more than eight feet from them, is a group of twelve men. Seven of these quite clearly, are carrying stones, and four are pelting objects at marchers just behind the officers of the law. No attempt was made by the police to intervene. Later a detachment of police did move up the embankment to discourage further throwing but, by this time, the roadway was littered with tens of hundredweights of rocks and bricks with broken glass strewn between the other debris. Dozens of marchers had been injured, and a number, including Michael Farrell, had to be taken to hospital.

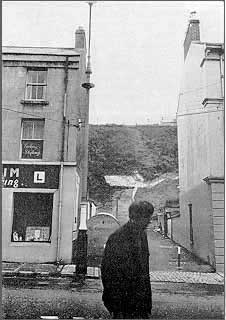

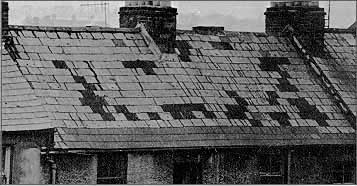

The shattered, bleeding remnants of the march now moved downwards towards the steep hill that is Spencer Road, and leads to Craigavon Bridge, then onwards to the centre of the town. We have described the ready piles of missiles available. And now the police behaved in a fashion for which it is difficult to find reasonable explanation. When the procession reached halfway down the street, the police, fully helmeted and protected, suddenly blocked its progress. Bricks, bottles and stones crashed down over the rooftops; the marchers hugged the shop fronts in the hope of avoiding injury. Some, wounded already from Irish Street and from Burntollet, sought refuge in the shops. Receptions differed sharply. A few shopkeepers gladly offered hospitality; others were grudging and nervous, and still more, feeling a common spirit with the attackers, physically or verbally propelled the injured back into the firing line. It is a matter of some importance to know who were the throwers at Spencer Road. Along the escarpment top were nearly three hundred people. These had moved directly from Irish Street, clearly following a well-prepared route along back roads from the time of Burntollet onwards. At the bottom of the slope, behind the houses, were about thirty people, stoutly clothed and wearing protective helmets against the inevitable shortfallings and inaccuracies of their fellows. The job of this front-line detachment was to pour stones down the side alleys directly towards the passing marchers. No force of policemen was stationed on the escarpment top. Yet everyone in the area well knew that this was a likely danger point. The situation is made even less credible by the fact that Waterside Police Station is set right in Spencer Road, just a few hundred yards from the attack point. Time and again the officers there have been subjected to complaints about casual throwers hurling rocks into the back of the shops and houses that made up the left-hand side of the marchers' route. A Civil Rights worker spoke with Head Constable Irvine, the man in charge of Spencer Road Station. He was clearly ill at ease, and readily admitted that the escarpment top was an obvious danger spot. Pressed to tell whether he had notified it as such to his superiors, he simply would not discuss the matter, though he freely admitted that anyone with knowledge of the area could have anticipated attack at that point. One of the residents of No. 36, Spencer Road, is Thomas Boyd, a full-time constable. As this house is set between the place where the stones were thrown, and the route of the march, a Civil Rights investigator called to ask what he had seen. Boyd said that he was off duty that morning and spent all the time at home. He heard nothing and saw nothing. Would he hold to this story despite the fact that slates in the roof were smashed and stones rained down smashing windows in adjoining houses and creating very considerable din? "I saw nothing, heard nothing, and will say nothing," he declared. Combining as he does the qualities of all three monkeys, Boyd also seems to suffer from a memory defect. He tells that he was "off duty" that morning. But according, to the Minister of Home Affairs, this oblivious young man was recruited into the regular constabulary during the week following the arrival of the P.D. march. For nearly a quarter of an hour police detained the marchers in a most vulnerable position in Spencer Road. Just a hundred yards ahead was the safety of an open bridge; stones rained down from the precise area about which the police authorities had been forewarned, and which they knew well from previous experience. Eventually, a detachment of police was sent in vehicles by a roundabout route to clear the missile hurlers from the heights. No thrower was arrested, or prosecuted later. The march was allowed to proceed to the bridge and from there, through a welcoming crowd of thousands, the marchers reached Guildhall Square. But before reaching this final destination they were subjected to another re-route. The police insisted that the procession should take a right-hand branch road, and not proceed through the old city walls that are a distinctive feature of Derry. This tactic later assumed more significance. Brought hastily from hospital, Michael Farrell spoke to the people of Derry. He was followed by various marchers of the People's Democracy, and the gravamen of their views is contained in one recorded address: "We came to this city because we know that its citizens have suffered at the hands of central and local government. The rate of employment here is disgraceful even in the context of this area of Northern Ireland. A corrupt and gerrymandered council has confined a deprived population to existence in intolerable slums. They have ensured their own continuance in power by shameless adjustment of local electoral boundaries. And they have been most ably assisted by their colleagues in Stormont. And latterly we have been promised, on your behalf, an empty reform. The council is to be replaced by nominees of the Stormont Government, of O'Neill or whoever may follow him, if the Orange Order do decide to finally get rid of him. "But, while we protest, with all the vigour we can summon, against the abuses of the system, we must not lose sight of our real enemy. Since January 1st, we have been attacked and harassed by groups of people who think they are hostile to what we represent. Today our marchers have been stoned and beaten, and right now many are in hospital. But these attackers are not our enemies in any sense. Largely, they are the Protestant people who are impoverished under the same predatory system. Impoverished they are, and wholly misled. We must show that we have no quarrel with them, but work only for the kind of society that will allow the deprived people, irrespective of religious views, to combine for their common good."During this address, the men of Burntollet and of Irish Street were arriving in the city. Passing freely through the city walls denied to the Civil Rights march, they were able to marshall in hostile force. Account after account tells how cudgel-bearing groups coming over Craigavon Bridge were automatically directed by the police to go inside the city walls. Now, as was inevitable, they were massing for action in an area just a few hundred yards up a steep hillside from Guildhall Square. Andrew Hamilton, an Irish Times reporter, was in this area shortly afterwards. He reports: "I visited the front line of the Paisley loyalists in Shipquay Street. There was a preacher man standing impassively in the midst of youths and men who were armed with sticks and staves and stones. There were hundreds of factory girls with curlers in their hair - and some of them were armed with sticks too. The preacher handed me a tract and said: 'It is the will of the Lord, my friend. The Lord is with us at this hour if we put our trust in Him'.Readers will recall that reference to the slopes of the River Faughan indicated that area where a succession of young girls had been thrashed by members of the now so jubilant mob. The song is an adaptation of a traditional lyric celebrating the triumph of the House of Orange over a futile Stewart monarchy using Ireland as the last bastion in their endeavour to regain power in these islands. But, as one of the stewards who was trying to keep the militant mob from advancing on the Civil Rights meeting, remarked: "They fought for civil and religious liberty in those days. And that is their slogan still. But hear what they have to say, and compare it with the views that Michael Farrell is prepared to uphold against even this vicious opposition."

|

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||