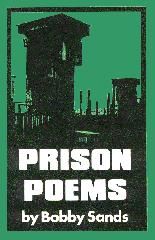

Extracts from 'Prison Poems' by Bobby Sands (1991)[Key_Events] Key_Issues] [Conflict_Background] HUNGER STRIKE: [Menu] [Reading] [Summary] [Chronology] [Dead] [Background] [Beresford_Chapter] [Sources] The following extracts have been contributed by permission of the publisher, Sinn Fein Publicity Department. The views expressed in this book do not necessarily reflect the views of the members of the CAIN Project. The CAIN Project would welcome other material which meets our guidelines for contributions.

Originally published by:

These extracts are included

on the CAIN site by permission of the publishers. You may not edit, adapt,

or redistribute changed versions of this for other than your personal use

without the express written permission of the publishers, Sinn Féin Publicity Department. Redistribution

for commercial purposes is not permitted.

by Bobby Sands who died on hunger-strike in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh on May 5th 1981, with an introduction by Danny Morrison

BOBBY SANDS was twenty seven years old when he died on the sixty sixth day of hunger-strike in the H-Block prison hospital, Long Kesh, on the 5th May 1981. The young IRA Volunteer who had spent almost the last nine years of his short life in prison as a result of his Irish republican activities was, by the time of his death, world-famous having been elected to the British parliament and having withstood pressures, political and moral (including an emissary from Pope John Paul II), for him to abandon his fast which was aimed at countering a criminalisation policy by the British government. That policy attempted to brand Irish resistance to the British occupation of Ireland as a criminal conspiracy without political motivation. In pursuit of that policy the British government attempted to force the prisoners to conform to regulations, wear a British criminal uniform and carry out compulsory, often degrading, prison work. The Irish republican prisoners who had been arrested under special laws, interrogated in special barracks (for example, Castlereagh) and sentenced in special non-jury courts refused to be criminalised and refused to recognise the authority of the prison regime, refused to wear the prison uniform or carry out prison work. In order to keep themselves warm the prisoners wrapped themselves in a blanket - and so the blanket protest began. For years the prisoners were held in solitary confinement and subjected to beatings, although due to overcrowding they eventually came to share a cell with another blanket man. In Armagh prison forty republican women also resisted the criminalisation programme and they too were persecuted by warders. From March 1978 until March 1981 the prisoners were on a no wash/no slop out protest which began when the prison authorities in a further attempt to break their will refused the prisoners access to toilets and washing facilities and forced the prisoners to live in filthy conditions. * * * As a young boy Bobby played in the fields around Carnmoney Hill and Glengormley in the shadow of Cave Hill where the founding father of Irish Republicanism, Wolfe Tone, almost two hundred years ago stood and swore to overthrow English rule in Ireland. During his formative years Bobby, as he says himself in his prison diary was "a budding ornithologist". As one well-known H-Block ballad goes, "...A happy boy through green fields ran/And kept God's and man's laws." He also read and was influenced by the nationalist poet Ethna Carberry (Anna McManus) who coincidentally also grew up in this part of Belfast. He always had an interest in Irish history and when the civil rights movement burst on to the streets in 1968 the reaction of the RUC to peaceful protest evoked a nationalist response in the hearts of most Catholic youths. He left school in June 1969 and worked as an apprentice coach-builder for the next three years. Bobby never expressed any sectarian attitudes, in fact, he ran for a well-known Protestant club - the Willowfield Temperance Harriers, and lived in a Protestant estate. But at work he came under increasing intimidation and by 1972 the family were forced out of their home by threats and attacks. They moved to Twinbrook - a new housing estate in nationalist west Belfast. Eighteen-year-old Bobby was the eldest in a family of four children, the others being, Marcella, Bernadette and John. Bobby had joined the IRA and in October 1972 he was arrested and charged with possession of four shortarms which were found in a house. In April 1973 he was sentenced to five years imprisonment which he served in the Cages of Long Kesh as a political prisoner. (Political status was wrung from the British government in June 1972 after a hunger-strike in Belfast jail.) During his time in prison Bobby was a voracious reader not just of Irish, but of world history, and he emerged from the prison in March 1976 as a radical republican dedicated to an Irish Socialist Republic. In Twinbrook he helped form a tenants association and a youth club whilst still working as a full-time IRA Volunteer. However, six months later he was arrested on active-service following a bomb attack on a furniture warehouse. There was a gun battle between the IRA unit and the RUC and two of Bobby's comrades were wounded. One shortarm was caught in the car and the four occupants were all charged with 'illegal' possession. Bobby was taken to Castlereagh where he was interrogated for seven days. He refused to talk to the Special Branch detectives and refused to recognise the court when charged. One of those also arrested with Bobby was Belfast man Joe McDonnell who replaced Bobby on the hunger-strike after his death and who himself eventually died after sixty-one days on the 8th July 1981. In September 1977 Bobby was sentenced to fourteen years imprisonment for having a shortarm and when he was brought to the H-Blocks he went on the blanket and resisted Britain's criminalisation programme which was aimed at sapping the prisoners' self-respect and maligning the integrity of the Irish People's struggle for self-determination This British policy had been employed against past generations of republican prisoners - against the Fenians in English prisons and against IRA Volunteers following the 1916 Rising. In resisting criminalisation IRA Volunteers had resorted to the hunger-strike protest, the most famous case being Terence MacSwiney MP, Lord Mayor of Cork who died on the seventy fifth day of hunger-strike in Brixton prison in 1920. In the H-Blocks Bobby began writing short stories and poems under the pen-name 'Marcella', his sister's name, which were published in 'Republican News' and then in the newly merged 'An Phoblacht/Republican News' after February 1979. He was P.R.O. of the protesting republican prisoners and succeeded Brendan Hughes as Commanding Officer of the blanket men when he took part in the first hunger-strike from October to December 1980. It was the failure of the British government to live up to the settlement of the first hunger-strike and to implement a promised enlightened prison regime which directly forced Bobby and his comrades on to a second hunger-strike. He led off the hunger-strike on 1st March 1981, two weeks in front of Francis Hughes, hoping that the sacrifice of his life and the political repercussions which it would unleash would perhaps force the British government into a settlement before any more of his comrades would have to die. However, by August 1981, nine other blanket men - Francis Hughes, Raymond McCreesh, Patsy O'Hara, Joe McDonnell, Martin Hurson, Kevin Lynch, Kieran Doherty, Thomas McElwee and Micky Devine - had also died on hunger-strike, due to British intransigence, itself secure by the inactivity of Irish politicians and Church leaders who did not raise their voices (or consciences) against Britain. On Saturday 3rd October 1981 the prisoners reluctantly abandoned their hunger-strike after a series of incidents in which families, encouraged by a campaign waged by the Catholic Church, sanctioned medical intervention when their sons or husbands lapsed into unconsciousness. The prisoners were effectively robbed of the weapon of the hunger-strike and so decided to end the historic fast which had lasted a marathon two hundred and seventeen days. * * * Shortly after Bobby went on hunger-strike the independent MP for Fermanagh and South Tyrone, Frank Maguire, who was a champion of the prisoners' cause, died of a heart attack. In the ensuing by-election Bobby stood on a 'political prisoner' ticket and was elected to the British parliament in a blaze of publicity. The result of that historic election showed the extent of support for the prisoners among the nationalist people (British propaganda had described the prisoners as having no support!) and should have been the occasion for the British Prime Minister, Mrs. Margaret Thatcher, settling the hunger-strike crisis. Instead the British not only refused to negotiate but enacted legislation to change the electoral law and prevent a republican prisoner candidate from standing for election. So much for British democracy! On the 5th May IRA Volunteer Bobby Sands MP died on the sixty-sixth day of hunger-strike. His name became a household word in Ireland, and his sacrifice (as did that of those who followed him) overturned British propaganda on Ireland and had a real effect in advancing the cause of Irish freedom. Some of his writings have already been published in pamphlet form and over 40,000 copies of his 'prison diary' have been sold. The majority of the following poems have never appeared in print before. Bobby wrote them during the last four years of his life in H Blocks 3, 4, 5 or 6. They were written on pieces of government issue toilet roll or on the rice paper of contraband cigarette roll-ups with the refill of a biro pen which he kept hidden inside his body.

H-BLOCK TRILOGY The H-Block Trilogy covers the 'conveyor-belt system' in the north of Ireland - interrogation, the Diplock Courts and the H-Block hell itself. In Castlereagh one is always watched. The Watcher is a uniformed RUC man who spies through the 'Judas', opens and locks the cell door and hands over the prisoner to detectives. The Watcher notes what one eats and when one goes to the toilet one is even watched on the seat. They see but don't witness healthy youths being taken out to interrogation and brought back battered and bruised. The only ventilation in the cells comes through a blast of air delivered from a vent above the cell door, it was from this vent that the RUC alleged that Brian Maguire hung himself in May 1978. However, the vent was of insufficient strength to support a man's weight and one of those rounded up and interrogated by the RUC around this time, Phelim Hamill, from Belfast, states that the RUC attempted to strangle him with a towel in order to make him sign an incriminating statement. He passed out on a number of occasions as a result of this choking. Also, the Amnesty International report of June 1979 reported that there were fourteen separate allegations of attempted strangulation reported by Castlereagh victims in this period. Most nationalist people believe that over-zealous RUC interrogators in attempting to force Maguire to sign a statement attempted to strangle him, that he did choke to death, and that they then staged the fake suicide to cover up for the murder. In this poem one can feel the fear creap through the prisoners who are always expecting the worst. Was it their turn for interrogation? There is a relative sigh of relief as the Watcher passes by one's cell to visit another poor victim. Throughout the Castlereagh poem Bobby returns to attacking those in society meant to uphold in culture or poetry or religion some defence of the oppressed. So the 'Men of Art' will sketch the moon but will never sketch 'the quaking wretch/Who lies in Castlereagh'. And the poets will write of the stars and gentle love but never of 'beauty tortured sore.' Suddenly in the poem the young republican having successfully withstood an interrogation finds himself confronted by ghosts "with faces white and small" (dead hunger-strikers?). They carried crosses bearing the name of Brian Maguire, they were the "marching dead," and they were bearded blanket men haunting the origin of their imprisonment and where one of their comrades, who never reached the H-Blocks, was murdered. Then they are suddenly replaced by the monstrous forces of darkness, representing British law and the rich who spun the thread for the "scaffold black" that murdered Brian Maguire. But, Bobby asserts, the beasts of Castlereagh will stand before God on Judgement Day and "must answer every sin." 'The Torture Mill - H-Block' opens with the violent death of a Screw, immediate joy' in the H-Blocks at his death and then reflection on how the system has regretfully made them hate. As the news reaches the prisoners there is an excitement and then a dread of the retaliation which will follow in the morning. To calm nerves men, denied cigarettes, roll up and smoke the threads of their very blankets. And then comes the dreaded dawn and the beatings. Bobby draws comparisons between the pleasures of life - dancing, falling in love, walking in the countryside, basking in the sun - with the terrible conditions in the H-Blocks. The humour of the poem, mixed as it is with tragedy, shows that Bobby has not been defeated and we can all share the triumph of the spirit of the prisoners over those adverse surroundings when we are told what happens as the Screws leave after inflicting beatings on everyone. Bobby draws from his own experience for these poems though they are by no means absolutely autobiographical. For example, Bobby was sentenced to fourteen years whereas the prisoner in 'Dip. lock Court' is sentenced to thirty years, and, of course, Bobby was arrested and in the H-Blocks years before Brian Maguire was killed in Castlereagh. In the 'Rhythm of Time' Bobby asserts that the spirit of freedom and injustice has been innate to man from the beginning, though he only draws upon its inspiration against life's experiences of evil. In tracing this spirit Bobby demonstrates an exceptional grasp of history and memory recall (he was denied books, newspapers, radio or TV, and mental stimulation for the last four years of his life). Wat the Tyler, for example, was an English peasant who in 1381 challenged and led an uprising against the English monarchy. The persecuted early Christians, slaves, peasants, the American Indians and Irish republican freedom fighters share the stage of history against tyranny. And the driving force against oppression, as Bobby concludes, is the moral superiority of the oppressed. * * * It has been said that were Bobby alive to see these poems today he would have rewritten or changed some of the simpler rhyming words. But that is to miss the point. These poems were written by a young man under the most depressing of conditions. More importantly his poetry is the raw literature of the H-Block prison protest which hundreds of naked men stood up against their cell doors (in the late of night when the Screws left the wings) to listen to and to applaud. It was their only entertainment, it was a beautifully rendered articulation of their own plight. Out of cruelty and suffering Bobby Sands harnessed real poetry, the poetry of a feeling people struggling to be free... - Danny Morrison, October 1981.

It is said we live in modern times, In modern times little children die, And while fat dictators sit upon their thrones, In the gutter lies the black man, dead, As the bureaucrats, speculators and presidents alike, For Barry's soul we prayed in hell, In the southern realms of Munster world, And they blow down lanes of time gone by, In dusky light, by mist, o'er hills they tread, Now Barry leads them in the night, And we prayed tonight for Barry's rest, And in darkened shadows, 'neath prison bars, *Tom Barry, an IRA commander in Barry's dead and Cork's asleep, The Rose of Munster's dead boys, Barry's dead, does no-one hear? Oh! cold March winds your cruel laments Oh! whistling winds why do you weep Oh! lonely winds that walk the night Oh! cold March winds that pierce the dark

As the day crawls out another night crawls in There's rain on the wind, the tears of spirits Toward where the evening crow would fly, my thoughts lie, Oh! and I wish I were with the gentle folk, I would gladly rest where the whin bush grow, There's an inner thing in every man, It was born when time did not exist, It lit fires when fires were not, It wept by the waters of Babylon, It died in Rome by lion and sword, It marched with Wat the Tyler's poor, It smiled in holy innocence,

It burst forth through pitiful Paris streets, It died in blood on Buffalo Plains, It screamed aloud by Kerry lakes, It is found in every light of hope, It lies in the hearts of heroes dead, It lights the dark of this prison cell, - Marcella, H-Block, Long Kesh Prison Camp.

|

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||