Centre for the Study of Conflict

Centre for the Study of ConflictSchool of History, Philosophy and Politics, Faculty of Humanities, University of Ulster

Centre Publications

[Background] [Staff] [Projects] [CENTRE PUBLICATIONS] [Other Information] [Contact Details] [Chronological Listing] [Alphabetical Listing] [Subject Listing] SPORT: [Menu] [Reading] [Main Pages] [Sources]

Sport and Community Relations in Northern Ireland

|

|

Sports |

Yes/No | Comments |

ANG |

NO |

Already built into sport |

BAD |

No |

Sport already integrated |

BAS |

Yes |

Belfast United side tours USA |

BOW |

No |

BOX |

No |

Not Necessary |

CYC1 |

No |

Already mixed |

CYC2 |

No |

Participate in Co-operation North maracycle |

EQU |

No |

Did not arise |

FOO |

Yes |

Cross-community courses/camps for children |

GAA |

Yes |

Scor festival brings young people together |

LGO |

No |

LHO |

No |

Trying to develop game in Catholic schools |

MHO |

No |

MCYC |

No |

Developing game at primary school level |

Only 3 sports reported having undertaken any formal initiatives in this area. Of these, the Belfast United project was not initiated by basketball itself but rather was an external cross-community scheme in which the sport agreed to participate. The Scor festival mentioned by the GAA may also be seen as having primary objectives other than those associated with community relations. All 3 initiatives are focussed on increasing cross-community contact amongst children and/or young people. Similarly the work being done particularly in hockey and rugby union to encourage more Catholics to play these games is directed at young people. There are no formal efforts to increase cross-community contact in sport amongst adults.

With regard to the consequences of such formal and other initiatives, most sports reported placing emphasis on increasing the awareness of young people from both communities about the activity concerned. In a similar vein others considered that broadening the participant base would increase the standard of sporting performance.

Only the two most popular sports, football and the amalgam of Gaelic activities, reported consequences beyond those strictly related to the individual sport. Football considered that cross-community initiatives had made people more aware of the problems faced by the two communities whilst Gaelic sport thought that their scheme helped reduce prejudice. Such claims must be treated cautiously but what is perhaps more significant is the propensity for sports to distance themselves from community relations responsibilities. In many respects this reflects fears that by becoming involved in such projects they risk being contaminated, or at least being seen in some way as contaminated by, problems of a sectarian nature. However cross-community projects such as the Co-operation North maracycle were supported, perhaps suggesting that such external initiatives are not perceived as directly impinging on sports reputation and therefore involvement is regarded in a largely positive light.

5.3: Community Relations Commitments

Sports were asked whether their constitutions and coaching programmes made any mention of community relations themes. In each case, if the response was negative, a further question was posed, asking whether they would be willing to introduce such ideas.

5.3.1. - Constitution

Table 14 provides a summary of the responses made by each sport as to whether, firstly, their constitution mentioned community relations, and, secondly, they would consider making the necessary amendments to incorporate such themes.

Table 14

|

Sports |

Mentioned? | Willing to Mention? |

ANG |

NO |

No |

BAD |

No |

No |

BAS |

No |

No |

BOW |

No |

No |

BOX |

No |

No |

CYC1 |

No |

No |

CYC2 |

No |

No |

EQU |

No |

No |

FOO |

No |

Could not answer |

GAA |

Yes |

N/A |

LGO |

No |

Could not answer |

LHO |

No |

No |

MHO |

No |

No |

MCYC |

No |

No |

Only 1 sport claimed to mention community relations. However, since this refered to the fact that the GAA was a non-political and non-sectarian organisation, a commitment echoed in the constitutions of many other sports, in effect it means that no direct mention of community relations themes is made by any sporting body.

5.3.2. - Coaching Schemes

Similar questions were asked as to the role of community relations in each sports coaching schemes. Table 15 shows the individual responses made.

Table 15

|

Sports |

Mentioned? | Willing to Mention? |

ANG |

NO |

No |

BAD |

No |

No |

BAS |

No |

No |

BOW |

No |

No |

BOX |

No |

No |

CYC1 |

No |

No |

CYC2 |

No |

No |

EQU |

No |

No |

FOO |

Yes |

N/A |

GAA |

No |

No |

LGO |

No |

No |

LHO |

No |

No |

MHO |

No |

No |

MCYC |

No |

No |

Only 1 sport; association football, reported making mention of community relations in their coaching programme. This was done at residential camps and coaching schemes for young people, normally held during the summer. Children from Protestant and Catholic backgrounds mixed together in groups and teams and the Department of Education for Northern Ireland (DENI), which provided grant aid for such activities, supplied speakers who discussed community relations themes.

5.3.3. - Conclusions

The evidence shows quite clearly that the majority of sports do not include and have no desire to include community relations themes in their constitution and/or coaching programme. This view is expressed quite articulately by boxing, a sport in which a substantial degree of mixing of Protestants and Catholics has successfully taken place. They report that they do not see themselves as having any role in terms of community relations. They are non-political and open to all and their objective is simply to win as many medals as possible, regardless of which side of the community they come from. This view is echoed by many other sports, stressing that there is no need for such steps to be taken within their activity and that recourse to such measures would only suggest sectarian problems do exist therein.

Once again, the fear of being seen in some way as having a problem appears to pervade the attitudes of sports towards taking any direct action in respect of community relations. The only example of such action; including community relations themes in coaching schemes for young footballers, seems to have been accepted both because it is recognised that footballs popularity and breadth of participant base make it a victim of the tensions in society as a whole and, perhaps more importantly, because extra funding has been made available for projects which incorporate community relations ideas.

This suggests that any efforts to force sports to embrace community relations in their activities would be met with, at best, ambivalence, and, at worst, open hostility. One sport reported having attended community relations seminars but having decided that it was inappropriate for them. At present, community relations themes appear to hold negative associations for a number of sports, related to fears that since their activity may be played largely by one community they may be identified as in some way sectarian or bigoted. Due to the prevalence of such fears the gains that community relations initiatives may bring to individual sports, perhaps through increased standards of performance and financial support, seem to be heavily outweighed by the potential costs in the minds of officials. If there are to be successful community relations initiatives in these sports, it seems clear that a great deal of work is going to have to be done to change pre-conceptions of what this means for the organisations concerned and to allay fears on the part of individuals associated with such bodies.

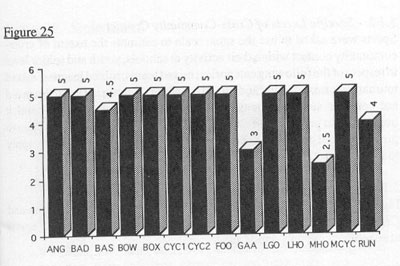

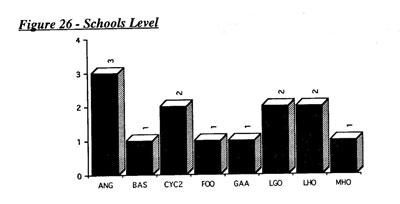

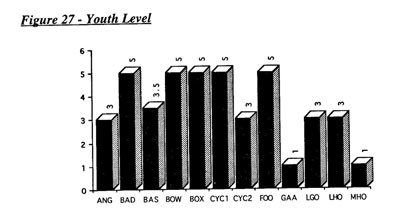

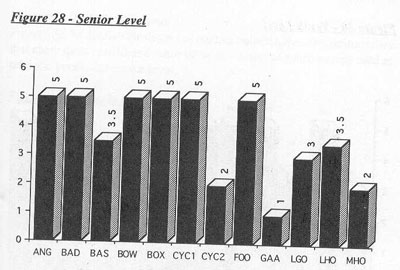

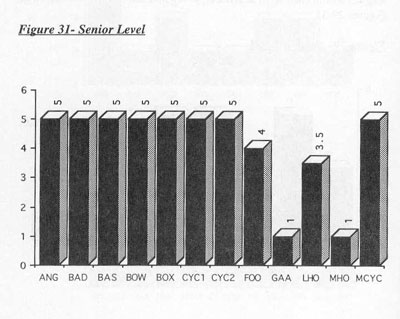

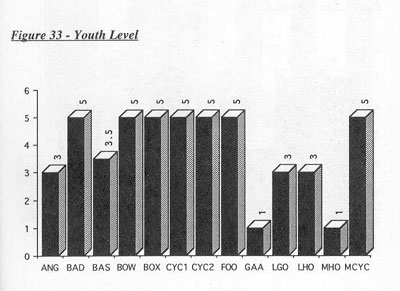

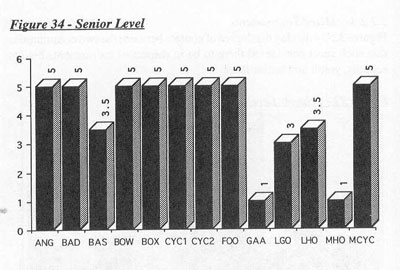

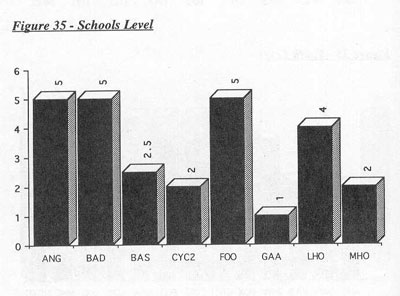

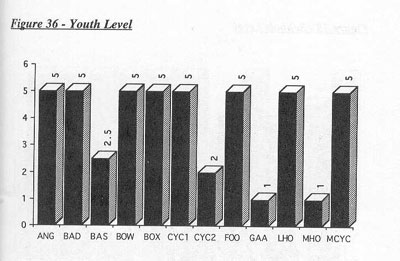

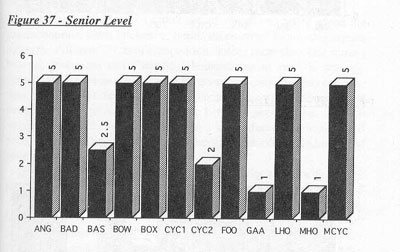

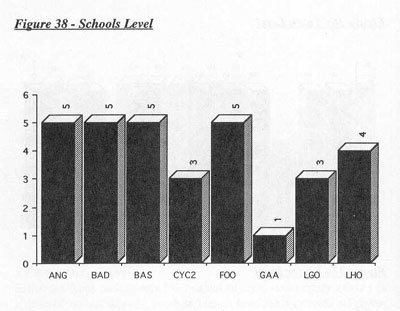

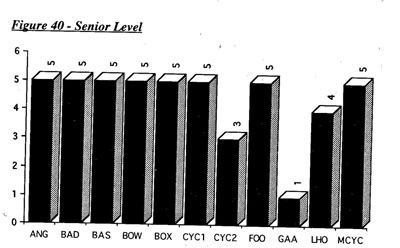

5.4: The Role of Community Relations

At this stage respondents were asked directly how they thought community relations initiatives should feature in the agenda for their sport in Northern Ireland. Again, a choice from a 1-5 scale was offered. Values ranged from not at all (1) to a great deal (5). An other category was added to the scale but was not used by any of the respondents. 14 sports provided an answer to the question. Equestrianism did not wish to express an opinion.

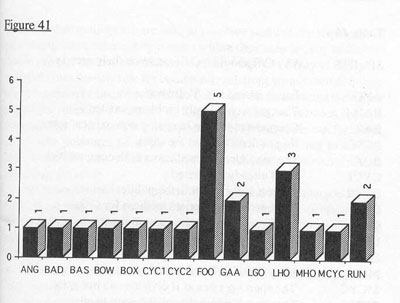

Figure 41 shows the degree to which each sport thought community relations initiatives should feature in their particular activity.

Figure 41

Four sports believed there was some role for community relations initiatives in their activities. Significantly, the only one which thought community relations should have a major role was football, which already undertakes work in these respects. The other sports which did identify some role for community relations were relatively popular activities with participant bases drawn predominantly from one community. However, whilst ladies hockey considered there to be a moderate role for community relations to play the mens game did not see any role at all for initiatives based on such ideas.

Table 16 gives a brief resumee of reasons why sports did not think community relations should feature on their agenda.Table 16

| Sports | Why C/R should NOT feature on their agenda |

| ANG | Issues related to CIR did not arise |

| BAD | Changes would imply problems existed |

| BAS | Counter-productive in raising non-existent issues |

| BOW | No problems exist in the sport |

| BOX | The sport already cuts across both communities | CYC1 | Sport already integrated | CYC 2 | Support C/R but not in the political sense | EQU | Sport not an appropriate medium for C/R | GAA | Little room for development in the sport | LGO | Has good record, little room for improvement | LHO | C/R has no direct bearing on the sport | MHO | "Contrived" C/R schemes do no good | MCYC | The sport operates as if divisions do not exist | RUN | The sport is non-political and open to all |

Table 17 provides a summary of reasons why sports did believe community relations should feature in their activities.

Table 17

| Sports | Why C/R should feature on their agenda |

| FOO | C/R good vehicle for bringing people together |

| LHO | Would like to develop game in Catholic community |

The view expressed by ladies hockey was echoed in comments from both mens hockey and rugby union.

Overall, the evidence from this section seems to strongly re-inforce the view that mention of community relations initiatives holds largely negative associations for the majority of sports. There appears to be a feeling that the introduction of formal community relations measures would be or would be perceived as a slur on the good names of the sports concerned. Respondents seemed to be averse to any initiatives being forced upon them, feeling that these would be counter-productive in raising issues which had not previously been present. Perhaps this suggests that until sports are able to perceive positive consequences of promoting cross-community contact within their activity, any initiatives which are undertaken should be selectively targeted. Many of the sports which did not see any role for community relations within their activities are of a relatively small-scale nature and it may be the case that their most important function in respect of improving relations between the two communities is in providing safety-valves whereby people can for a time escape the pressures of wider social conflict. Attempting to enforce community relations schemes within such activities may well have more costs than gains.

However, amongst those sports with larger and/or broader participant bases, there may be more room for community relations initiatives to be successfully undertaken. The work done by football in respect of mixing young people from both communities, although its long-term effect on attitudes is uncertain, has had short-term benefits, particularly for the sport itself both in bringing in extra financial support and expanding the pool of talent available.

Other sports concerned about standards of performance in their game within Northern Ireland, particularly those which tend to be the preserve of one religious community, may be interested in such developments, especially if additional resources are made available. At the same time, as shall be seen in the case-studies, there are also risks involved in having substantial levels of participation from both communities. Before sports are prepared to embrace community relations initiatives considerable doubts shall have to be overcome and those activities such as hockey and rugby which currently have problems associated with issues of national allegiance may be reluctant to risk rocking the boat any further through participation in such schemes.

Perhaps the greatest potential for progress exists in those sports which are already widely played by both Protestants and Catholics and have sufficient levels of participation from those people who are situated at what has been described as the cutting edge of the conflict. A good example of what is possible shall be seen in boxing where young working-class men from both communities take part at all levels of the game and few problems of an openly sectarian nature have arisen. Conversely, another sport which is played by both communities; cycling, has been split in an overtly political manner. Football, despite its work with young players, has been afflicted by serious disorder, largely amongst spectators and often, though by no means exclusively, with sectarian connotations.

With a view to exploring further what possibilities for progress there may be for community relations in sport these activities, along with the more middle-class sport of hockey, are examined in detail in our case-studies.

5.5: Change Since 1970

It was thought important to add a dynamic element to the information concerning the degree of cross-community contact within individual sports in Northern Ireland. To this end a question was designed asking how each sport had changed in respect of cross-community involvement on the religious dimension since 1970, at the outset of what has become known as the Troubles. A choice was offered from the following categories; that the sport had become totally integrated; more integrated; was much the same; had become more polarised; and totally polarised. Sports were also asked to account for any change there had been in that time.

Fourteen sports provided answers to this question. Equestrianism considered it inappropriate and did not answer. A summary of the information obtained from each sport regarding change in the degree of cross-community contact since 1970 is given in Table 18.

Table 18

| Sports | Change in cross-community contact since 1970 |

| ANG | More integrated |

| BAD | Much the same |

| BAS | Less integrated (80s)/More integrated (90s) |

| BOW | Much the same |

| BOX | More integrated | CYC1 | Totally integrated (Ire)/Totally polarised (NI) | CYC 2 | Less integrated | EQU | Sport not an appropriate medium for C/R | FOO | More integrated | LGO | More integrated | LHO | Less integrated | MHO | Much the same | MCYC | Much the same | RUN | More integrated |

Of those sports which provided a clear answer, 5 considered their activity to have become more integrated since 1970; 2 thought they were less integrated; and 5 believed things were much the same.

Table 19 provides a resumee of the reasons sports offered to support the view that they had become more integrated.

Table 19

| Sports | Reasons for greater integration since 1970 |

| ANG | Better organisation, communication, information |

| BAS | Media coverage encouraged more Protestants to play |

| BOX | Local successes encouraged wider participation | CYC1 | The amalgamation of cycling bodies in Ireland | FOO | Residential schemes, coaching schools, C/R work | LGO | Being seen as mixed encouraged wider participation | RUN | World Cup, mini-rugby brought in more Catholics |

The reasons offered for sports believing that they had become less integrated since 1970 are shown in Table 20.

Table 20

| Sports | Reasons for greater polarisation since 1970 |

| BAS | Protestant schools gave up sport in 80s |

| CYC1 | Split and hostilities within sport in NI |

| CYC2 | Split led to fall in numbers in sport in general | LHO | Catholic schools have given up game |

Of those sports which considered there to have been no change in respect of levels of cross-community contact both badminton and motor-cycling believed this was because their sport had always been totally mixed. Bowls thought that the fact it was seen to be free of sectarian problems had led to it becoming slightly more integrated but only to a small degree.

Again there may be a tendency amongst sports to paint a rosier picture in terms of change than is actually the case, but the range of answers suggests a fair degree of realism has been applied. Cycling is the most obvious example of a sport severely afflicted by divisions since 1970 and this is reluctantly acknowledged by both bodies concerned. Other explanations of sports becoming less integrated seem once again to be restricted to factors external to the activities concerned, especially to do with the educational system.

Only football considers greater integration to be in any way connected to developments in the community relations field. Other explanations revolve around increases in the general popularity of sports, particularly where there has been local success and/or increased media coverage. It may perhaps also be significant that the two sports reported to be most exclusivist in terms of religious background; Gaelic sports (99% Catholic) and mens hockey (95% Protestant) were amongst those which had experienced no change in terms of cross-community contact over the period.

Last Modified by Martin Melaugh :