Centre for the Study of Conflict

Centre for the Study of ConflictSchool of History, Philosophy and Politics, Faculty of Humanities, University of Ulster

Centre Publications

[Background] [Staff] [Projects] [CENTRE PUBLICATIONS] [Other Information] [Contact Details] [Chronological Listing] [Alphabetical Listing] [Subject Listing] SPORT: [Menu] [Reading] [Main Pages] [Sources]

Sport and Community Relations in Northern Ireland

|

| Sports | How Affected by Conflict |

| ANG | Discourages outsiders travelling to NI |

| BAD | Travel in 70s/in certain areas |

| BAS | Not played by Prot schools in 80s |

| BOW | Travel in 70s/security force participation |

| BOX | Crowds and minor re-scheduling in 70s | CYC1 | Organisational split within sport | CYC 2 | Security force participation | EQU | None | FOO | Britain/World | GAA | In certain areas/finance during H block protests | LGO | Discourages outsiders travelling to NI | LHO | Travel in 70s/hosting inter-provincial championship | MHO | Security force participation | MCYC | None | RUN | Not played by Cat schools/perceived as British |

Amongst the most common factors mentioned were problems to do with players, spectators and teams travelling to and from certain areas within Northern Ireland. Several sports reported that such difficulties had arisen at the height of civil unrest in the 1970s but had since ceased to be a problem. For example, bowls mentioned that in the 1 970s 2 clubs situated in West Belfast had suffered as a result of travel difficulties which made other teams and/or individual players unable or unwilling to play as scheduled.

In football, Northern Irelands home fixtures were staged in England for a time during the early 1970s and although international sides returned to Belfast during the course of the decade England and Wales refused to travel to the province during the Hunger Strike protest of 1981. Even today Cliftonville are not permitted to play at home against Linfield.

Other sports found it difficult to attract people from outside Northern Ireland to play here. Ladies golf mentioned a particular problem in attracting participants from the south of Ireland. The inter-provincial championship, usually staged in Northern Ireland every 5th year, had not been held here since 1985, although an all-Irish tournament was to take place during the course of 1993. Angling also reported problems attracting outsiders to travel to Northern Ireland, particularly since several since off-duty members of the security forces were killed in a car bomb while on a fishing expedition to Fermanagh in the early 1980s.

A number of sports reported difficulties arising as a result of teams and/or individuals who were members of the security forces participating in their activity. The most common set of problems were again related to travel to and from certain areas, commonly, in sports with all-Irish structures, in the Republic of Ireland. Other sports had made special arrangements to protect the identities of players who were in the security forces such as allowing them to play under assumed names and to be accorded temporary membership of civilian teams.

As far as community divisions were concerned, two sports mentioned the fact that their activity tended to be played by one side rather than the other but both emphasised how bound up this was with the regions divided educational system. Rugby union pointed out that the majority of Catholic schools did not play rugby as it had been perceived as a British sport, although they felt the barriers were beginning to break down. Basketball reported that Protestant schools had given up the sport for unknown reasons in the 1980s but again believed there to have been something of a resurgence. Conversely, football considered that its problems were largely due to the fact both communities participated extensively in the game which meant that from time to time wider social tensions were "inevitably" reflected in the sport.

Again, despite the fact that respondent sports may be likely to play down the impact the Northern Ireland conflict has on their activity, a fairly wide range of problems were reported. Most sports seemed to suggest or state openly that the direct effects had reduced since the 1 970s as the shape of the conflict had changed but indirect effects such as those related to the schools system had proved to be longer standing. However, of all the respondent sports, football alone appeared to articulate a view that despite the conflicts influence, there remained some prospect of community relations schemes bearing fruit when applied to sport.

4.1.3 - The Consequences of Impact

Sports were asked a further question in this subject area, inviting them to give details of any consequences which had arisen from the impact of the conflict on their sport. Table 11 provides a brief summary of their responses.

Table 11

| Sports | Consequences of conflict's impact |

| ANG | Reduction in tourists/loss of government support |

| BAD | No lasting consequences |

| BAS | No lasting consequences |

| BOW | No lasting consequences except security forces |

| BOX | None | CYC1 | Organisational division/hostility between bodies | CYC 2 | No lasting consequences except security forces | EQU | None | FOO | Increased participation/improved facilities | GAA | Loss of revenue/problems training and playing | LGO | Fewer tournaments held in NI | LHO | Temporary isolation from international scene | MHO | No lasting consequences except security forces | MCYC | None | RUN | Difficult to encourage Catholics to take up game |

A number of sports reported there to have been no serious consequences with the exception, in some cases, of security force participation. 2 respondents mentioned financial consequences. The GAA experienced temporary difficulties at a time of particular political crisis (the Hunger strikes) for the community which constitutes its membership. A more enduring problem reported by angling was the difficulty of persuading tourists to travel to Northern Ireland which they believed in turn led to underfunding by government of the provinces potentially lucrative fishing reserves.

The consequences of losing out on international competition were also mentioned, the fear being that if top events were not staged in Northern Ireland the encouragement and inspiration young people needed to pursue the sport would be absent. Within cycling, the 2 governing organisations once again presented different viewpoints as to whether the split which occurred was a consequence of the political conflict or simply divisions within the sport.

It is perhaps interesting to note that football again is out on its own in considering that there may have been positive consequences for the sport. They report that more people have taken up the game, presumably as some kind of safety-valve from the tensions in wider society and, as a result of the increase in numbers, facilities have also improved.

Whilst again there is likely to be a tendency amongst sports to play down the consequences political conflict has on their activities, at least half of those included in the sample survey acknowledge that prevailing community tensions have some effect. Most of these consequences, understandably, are perceived in terms of a loss to the individual sport, for example, in respect of finance, numbers participating or the quality of competition. There is little mention, except in cycling and football, of the effect wider social and political divisions have on sport and within one of these there is disagreement on this point whilst in the other an alternative view of sport as a safety-valve appears to be tacitly expressed.

4.2: Impact of Divided Community Structure

More precise information was thought to be required as to the role of community divisions within each sport. Thus, respondents were asked to estimate the impact of Northern Irelands divided community structure in terms of the following categories; recruitment; travel; location; spectator violence; fixture scheduling; public image/relations; standards (of performance); and other. A 1-5 scale was again used to measure impact in each category, values ranging from none at all (1) to a great deal (5).

4.2.1. - Impact on Recruitment

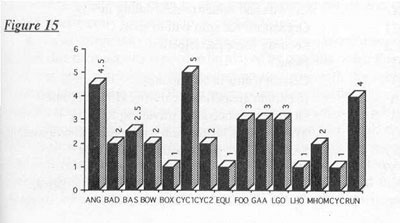

Figure 16 shows the impact each sport considered the provinces divided community structure to have on recruitment to their activity.

Figure 16

Only 4 of the 14 sports which responded believed community divisions had any impact on recruitment. Within cycling one governing body believed the divided community structure had a major impact whilst the other believed it had no impact at all. Rugby union, which might be considered to be affected by such divisions in so far as the game is almost exclusively played by Protestant grammar schools, did not answer this particular question.

When the information highlighted in Figure 14 about the religious composition of each sport is taken into account, it may seem surprising that so few acknowledge community divisions to have had an effect on recruitment. What appears more surprising is that, with the exception of ladies hockey, the sports which reported the most even divisions in respect of religious composition are those which considered the divided community structure to have most influence; basketball (60-40 Catholic); cycling 1(50-50); and football (55-45 Catholic).

There may be a general reluctance on the part of governing bodies of sports predominantly made up of one religious group to acknowledge the impact of community divisions on recruitment for fear of this being interpreted as an admission that barriers exist within the sport itself. Respondents placed emphasis on the fact that their sports were non-sectarian and open to all and possibly felt uneasy about recognizing restrictions (albeit externally imposed) on recruitment from both communities.

4.2.2. - Travel

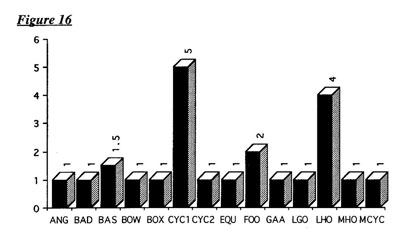

Estimates of the impact of Northern Irelands divided community structure on travel are illustrated in Figure 17.

Figure 17

Only 2 sports identified community divisions as having any impact on travel. One of these, mens hockey, perceived an impact only in so far as teams representing the security forces were concerned. Otherwise, all sports thought the divided community structure had no effect.

This may again seem surprising given the number of sports which mentioned travel in some form or other as presenting difficulties within their sport as a result of the Northern Ireland conflict. However it may be that this apparent contradiction is due to the divided community structure and the conflict being seen as largely independent of each other; one perhaps identified as being externally imposed, the other interpreted as, at least to some extent, throwing doubt on the way the sport itself operates.

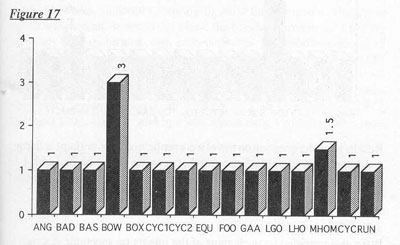

4.2.3. - Location

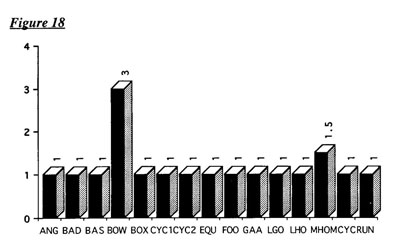

Figure 18 shows the impact community divisions were seen to have on location within each sport.

Figure 18

Results from the question on travel were replicated here, perhaps reflecting some confusion over the distinction between the two. Football added the qualification that community divisions had no impact except in respect of the Cliftonville-Linfield fixture.

4.2.4 - Spectator Violence

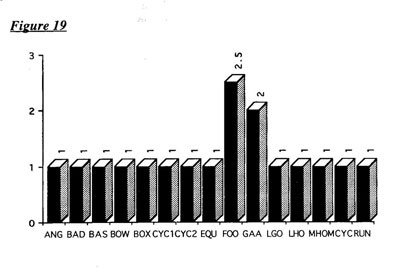

Estimates provided by each sport of the impact on spectator violence of Northern Irelands divided community structure are shown in Figure 19.

Figure 19

Only 2 sports reported community divisions as having any impact in respect of spectator violence. Not surprisingly, these are by far the most popular sports in terms of participation and are amongst the few included in the sample which attract crowds of sizeable proportions as spectators.

Given that crowds at Gaelic matches are likely to be drawn predominantly from the Catholic community, it is questionable whether community divisions directly precipitate spectator violence within this sport. However, indirectly, bearing in mind the political environment within which such fixtures take place, the divided community structure may well have an influence on such violence. In football examples of spectator violence between supporters from Protestant and Catholic communities are self-evident, although it should be borne in mind that such violence also occurs between spectators of clubs from the same community, examples being provided by the Irish Cup Finals of 1983, 1985 and 1992, all contested by clubs with strong, Protestant traditions.

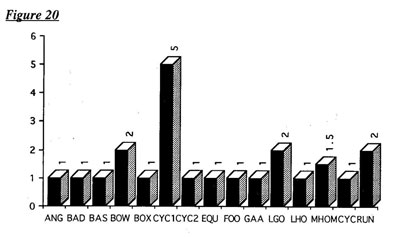

4.2.5. - Fixture Scheduling

Figure 20 shows estimates of the impact each sport considered community divisions to have in respect of fixture scheduling.

Figure 20

Five sports considered Northern Irelands divided community structure to have had some impact on fixture-scheduling. Of these mens hockey again thought its influence to be limited to teams from the security forces. One cycling organisation considered there to have been a major impact due to the fact that races are now organised separately by UCF or NICF. The other cycling organisation, however, considered the only impact to have been in so far as 28 days notice was required by the RUC for road events to be sanctioned. A clue to explaining the contrary nature of such responses may be provided by ladies hockey which said that fixtures had been re-scheduled in the 1970s but that this was due to the Troubles rather than community divisions. Whilst some sports may indeed have suffered fixture disruption, there appears to be a reluctance to interpret this as being a direct result of Northern Irelands divided community structure. It appears that, at least in the minds of governing body officials, there is little connection between the troubles, everyday life and sport in Northern Ireland.

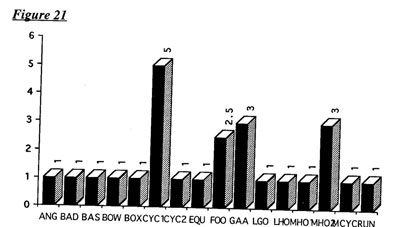

4.2.6. - Public Image/Relations

Estimates of the impact community divisions have on each sports public image and/or public relations are shown in Figure 21.

Figure 21

Four sports reported having suffered in respect of their public image and! or public relations due to the divided community structure in Northern Ireland. Significantly, these included both of the most popular participant sports included in the survey sample - football and the amalgam of Gaelic sports.

Cycling was again divided over the issue although the organisation which considered there to have been no impact did say that its public image had been affected at the time of the split within the sport by being depicted as a bigoted and sectarian body. However, more recently it had become clear that the organisation was open to all and its profile had been restored. In mens hockey alternative responses were also obtained. The respondent who had supported adopting a British organisational base believed that its public image had been affected to a moderate degree by community divisions. Bowls considered that its image had actually been boosted by the fact it was widely seen as free of sectarian conflict.

Bearing in mind that the sports reporting community divisions to have had no impact on their public image/public relations included rugby union, where a problem was reported in so far as the game was perceived by the Catholic community as British, there may again have been a tendency towards under estimation. However, the fact Gaelic sports and football did acknowledge the community structure to have had some influence on their public image does suggest that the greater the numbers participating, the more likely there is to be a problem. In this respect boxing appears to provide something of an exception. Cycling and, to a lesser extent, hockey illustrate how different interpretations can be made of the public profiles of individual sports, dependent on the viewpoint of each respondent.

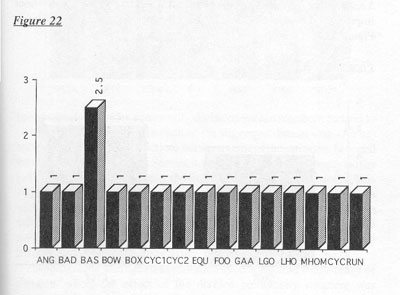

4.2.7. - Standards of Performance

Estimates of the impact of Northern Irelands divided community structures on the standards of performance within each sport are shown in Figure 22.

Figure 22

Only 1 sport reported community divisions having any influence on standards of performance. Basketball considered there to have been a drop in standards during the 1 980s when the game tended not to be played by the Protestant community. None of the other sports in which one community predominated, such as hockey, rugby union or Gaelic sports, identified any impact on standards.

However, in all of these sports efforts were being made to encourage youngsters from both communities to play. The objective behind such programmes would often be stated as an improvement in standards of competition. Once again, a partial explanation of this apparent contradiction may lie in the way in which the question is interpreted. Whilst sports may not consider the divided community structure to be directly related to standards of play, several mentioned the division of education in Northern Ireland as a major factor in determining why a particular sport was the preserve of one community and why, as a result, they lost out on potentially top-class sportsmen and women from across the community divide.

4.2.8. - Other Effects

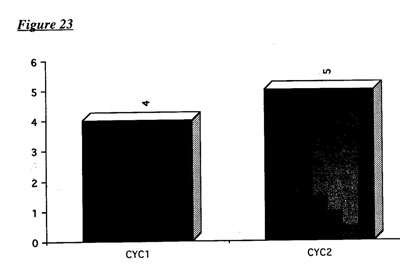

Sports were asked to specify and, if possible, evaluate on the standard 1- 5 scale, other respects in which Northern Irelands community divisions impinged on their activities. 2 estimates were obtained, as detailed in Figure 23.

Figure 23

Despite the wide gulf between the two cycling bodies in many other answers, both considered the organisational division within their sport to have had a major impact. One tied in verbal abuse and hostility between officials particularly around the period of the split in 1987/88. In contrast football believed the sport had been affected in some positive ways by increasing awareness of the sensitivities of both communities within their sport, leading to a more sympathetic approach in deciding, for example, the venues for semi-finals and finals.

4.2.9 - Conclusions

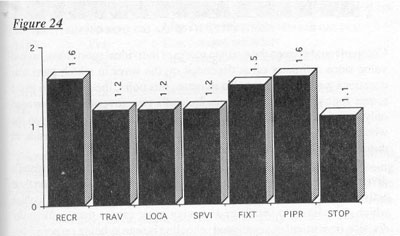

Figure 24 shows the approximate average scores for each element of the divided community structure which sports were asked to evaluate.

Figure 24

Sports clearly consider community divisions within Northern Ireland to have little general impact in each of the suggested dimensions. As has been seen there are contradictions between some of the estimates here and the information obtained in Section 4.1. with an apparent tendency on the part of sports to under estimate the impact of community divisions. This may be a matter of interpretation or an instinctive defence mechanism against suggestions that there may be something wrong within the individual sport in terms of bias or prejudice. Nonetheless the low general estimates do help place the problems that arise within sport in Northern Ireland in some kind of perspective.

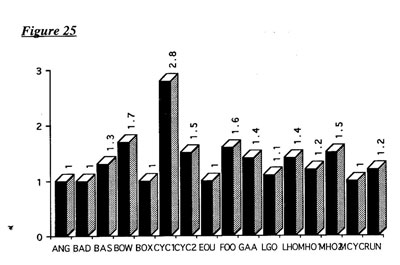

Approximate average scores for each sport across the whole range of elements where the effect of the divided community structure was assessed, are shown in Figure 25.

Figure 25

Comparisons between the average scores of individual sports have limited value since estimates often depended on the ways in which particular questions were interpreted. To illustrate this point, the difference in the scores for cycling from Northern Irelands two governing bodies need only be scrutinised. One body interpreted questions as referring to the whole of cycling within Northern Ireland whilst the other only considered those aspects of the sport under its jurisdiction.

Nonetheless the scores do show that sports consider Northern Irelands divided community structure to have had only a marginal impact on their activities. There may again be a tendency to play down the difficulties which do exist or to see them as having other causes than community division (in particular, segregated schooling is seen as being responsible), perhaps due to understandable concern at being identified as a problem sport. It does seem, however, that certain sports, whilst recognising that the Northern Ireland conflict impinges in some respects upon their activities have great difficulty in going a stage further and establishing a direct relationship with the prevailing community structure.

4.3: Impact of Conflict on Other Sports

Sports were also asked if they considered other sports to be affected by the conflict in Northern Ireland and, if this was the case, to give brief details. Table 12 provides a summary of the responses made by each sport.

Table 12

|

Sports |

Yes | No |

ANG |

Yes |

Discourages outsiders/restricts competition |

BAD |

No |

May affect particular sports |

BAS |

Yes |

Some more than others |

BOW |

Yes |

Travel problems/particular sports (football) |

BOX |

Yes |

Particular sports (football) |

CYC1 |

Yes |

Particular sports (rugby union) |

CYC2 |

Yes |

Security force participation |

FOO |

NO |

Less cross-community participation in others |

GAA |

NO |

May be travel problems |

LGO |

Yes |

Discourages outsiders |

LHO |

Yes |

Discourages outsiders/particularly team sports |

MHO |

Yes |

Particular sports (football, Gaelic) |

MCYC |

Yes |

Particular sports (football, Gaelic) |

RUN |

Yes |

Some sports split |

Fourteen sports provided answers to this question, 1 (Equestrianism) refused to express a view. Bearing in mind that respondents were being asked a fairly sensitive question about matters beyond their own remit the quantity and breadth of answers may be seen as exceeding expectations. Understandably, there was a degree of ambiguity in some responses. However, a number of suggestions as to the nature of the conflicts influence reinforce those made by individual sports concerning their own activity. In particular, travel, security force participation and the effect on outsiders, are mentioned.

Whilst a fair amount of caution should be exercised in assessing the significance of such responses, they do reflect some basic, general awareness of the impact on sport of the community setting within which it is played.

Last Modified by Martin Melaugh :