Centre for the Study of Conflict

Centre for the Study of ConflictSchool of History, Philosophy and Politics, Faculty of Humanities, University of Ulster

Centre Publications

[Background] [Staff] [Projects] [CENTRE PUBLICATIONS] [Other Information] [Contact Details] [Chronological Listing] [Alphabetical Listing] [Subject Listing] SPORT: [Menu] [Reading] [Main Pages] [Sources]

Sport and Community Relations in Northern Ireland

|

| Grammar Schools: | 2.9 |

| Secondary Schools: |

2.5 |

| Church-based Youth: |

1.7 |

| Community-based Youth: |

1.6 |

Beyond these, the frequency with which the influence of family and friends and local factors were mentioned may be significant.

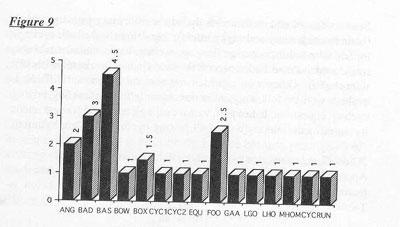

Levels of influence ranged from sports such as equestrianism and motor cycling where all proferred sources had no influence to basketball where all were considered to have a major influence. The low estimates for the former activities may be explained by the technical nature of the sports concerned which makes it difficult or impossible for them to be promoted in a school or youth organisation context.

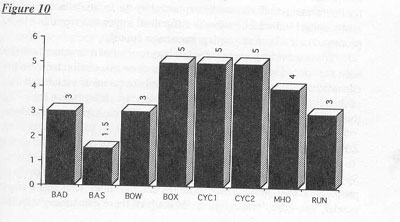

The relative importance of schools as sources of recruitment may be seen as supporting the view that there is a close association between the educational system in Northern Ireland and the nature of social activities such as sport. However, to gain a fuller perspective, information regarding the social composition of people who take part in each sport was obtained.

2.3: Social Composition

Sports included in the survey were asked to estimate the make-up of people who took part in their particular activity in terms of social class, gender, age-group and religion. In each of these categories, with the exception of age-group, estimates were to be based on a simple dichotomy in order to standardise as far as possible the bases on which responses were made and minimise confusion. However, a number of sports found it difficult or impossible to provide estimates to fit the format of the questions. It was as if this was the first time the respondents had ever conceived of their sports in social and cultural terms.

2.3.1 - Social Class

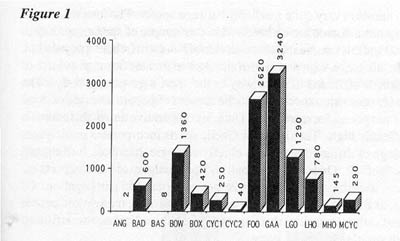

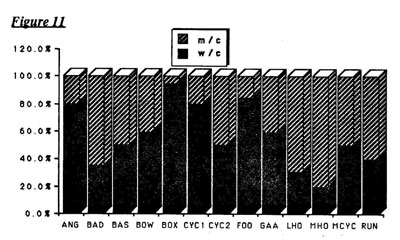

Here sports were asked to estimate the balance between participants of working-class (manual) and middle-class (non-manual) backgrounds. 13 sports provided estimates of this information, shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11

6 sports reported a working-class bias; 4 reported a middle-class bias; and 3 reported an even division. Both sports which could or would not provide an estimate (ladies golf and equestrian sports) appear likely to have a middle-class predominance, suggesting a fairly balanced sample of sports in this respect.

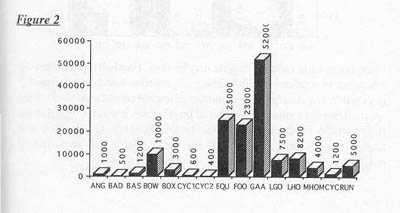

When the numbers participating in each of the 13 sports, as detailed in Figure 2, are taken into account, the total social class balance is weighted approximately 60:40 in favour of the working-class. Again, bearing in mind that the two sports which did not respond are likely to be mainly middle-class in composition, a fairly even division seems to have been obtained. Since, amongst the population at large, there are likely to be more people (in terms of this simple division) in the working-class, this might suggest that individuals from middle-class backgrounds are more likely to become involved in organised sporting activities.

2.3.2 - Gender

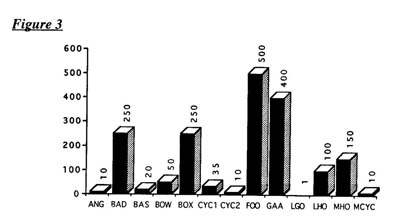

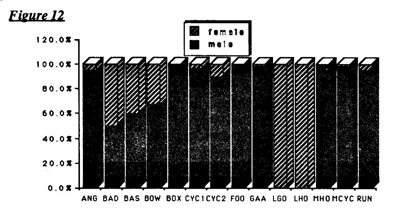

14 sports provided estimates of the gender balance amongst participants in their activity. Figure 12 shows this information.

Figure 12

11 sports are predominantly or exclusively male in composition; 2 sports are exclusively female; and 1 sport reported an even division. It is highly likely that the sport which did not respond; equestrian sport; may be an overwhelmingly female sport. The 2 sports reporting to be exclusively female were specific governing bodies for women in activities also played by men.

When the numbers participating in each of the sports, as given in Figure 2, are taken into account the overall male:female proportion approximates around 82:18. It is hard to escape the conclusion that sport is still largely a mans world, at least as far as organised competition is concerned.

2.3.3 - Age-Group

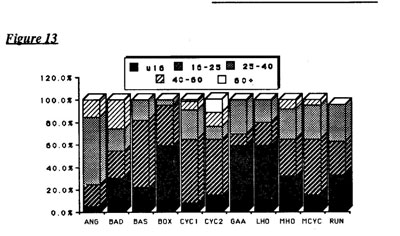

Sports were asked to estimate the age profiles of people who participate in their activity. To this end five age-groups were suggested; under 16; 16-25; 25-40; 40-60; and 60 plus. Respondents were asked to estimate the proportion of participants who came into each category. A number of sports found this exercise to be difficult and/or complex. 11 were able to make full estimates while another 3 could only provide partial answers. Figure 13 shows the estimates of the 11 sports who provided complete answers.

Figure 13

Football estimated that all players would be found within the first three age-groups but due to the vast numbers involved was unable to differentiate between them. Ladies golf placed the age-groups in the following order as far as numbers were concerned; 1st: 40-60; 2nd: 25-40; 3rd: 60+; 4th:U16; 5th: 16-25. Bowls placed age-groups in the following order; 1st: 40-60; 2nd=: 60+ and 25-40; 4th: 16-25; 5th: U16.

When the information from the sports who provided complete estimates is examined it appears that organised sporting activities are largely the preserve of people under 40. Within that category there is a fairly even division between the three age-groups. Mean proportions based on the 11 sports cited in Figure 14 approximate around the following: 38% for the 25-40 group; 31% for the under 16s; and 26% for the 16-25 age-group. The predominance of under 40s would be reduced somewhat by the inclusion of figures for ladies golf (and, presumably, mens golf also) and bowls. However, if numbers participating in each sport were to be taken into account, the inclusion of football would significantly re-inforce the under 40 bias. The conclusion, perhaps predictably, is that sport on an organised level is played largely by younger people.

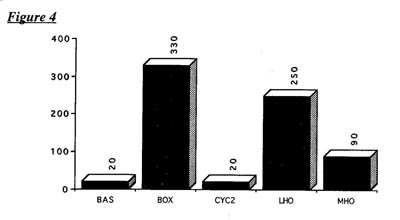

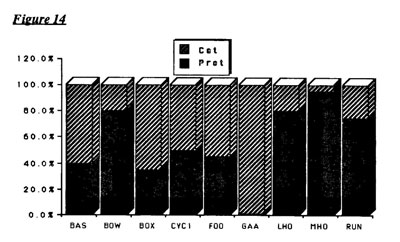

2.3.4 - Religion Sports were asked to estimate the religious balance amongst people taking part in their activity. This was to be done on the basis of a simple Protestant:Catholic divide. A number of respondents were unable and/or unwilling to answer this question. Some said that it was impossible to provide an estimate as their activity was open to all and they did not ask about and were not interested in peoples religious backgrounds. Others could not estimate proportions but expressed an opinion as regards the likely balance in their sport. 9 sports provided a more or less complete answer. Figure 14 shows the estimates of proportions of Protestant and Catholic participants within these sports. Figure 14

The figure for football is based upon players in the Irish League. There was thought to be a slight Protestant bias at lower levels, although this was considered impossible to quantify. The estimate for rugby union is made on a 9 county basis and therefore, in the context of Northern Ireland, there is likely to be a greater Protestant predominance.

Four sports (Angling, Badminton, Cycling [NICF], Ladies Golf) could not provide estimates but thought there was a higher proportion of Protestants than Catholics taking part in their particular activities. It was suggested (from an external source) that the Protestant predominance in the membership of the NICF cycling organisation may be as substantial as 90:10. Motor cycling could not provide an estimate but thought the sport was evenly mixed.

When the numbers participating in each sport, set out in Figure 2, are taken into account, the overall balance across the 9 sports who provided estimates approximates to a 68:32 Catholic predominance. However, when the estimate for Gaelic sports (with 52,000 reported participants) is removed the balance changes significantly, approximating to a 60:40 Protestant advantage. Once more, for reasons outlined above, these figures should be treated with caution.

Table 2 shows the number of sports in which each religious group was considered to be the largest. Estimates from all 14 sports are accounted for here.

Table 2

| Protestant: |

8 |

| Catholic: |

4 |

| Mixed: |

2 |

What emerges in this social sphere is a much more complex picture than those found in respect of social class, gender or age-group.

Gaelic sports are the only virtually exclusive activities included in this survey in terms of religion. Since around one-third of all the sportsmen and sportswomen considered here play these sports their influence on any general perspectives obtained is substantial.

When all 15 sports, including those organised by the GAA, are considered as a whole, Catholics appear to be over-represented in organised sporting activities. However, when Gaelic sports are excluded and the likely under-estimation of Protestant predominance in two other major sports; football and rugby union is taken into account, the perspective changes radically into one in which Protestants seem likely to be over-represented. It also appears to be the case that the sports which have a Protestant predominance are more reluctant to report this than those which consider themselves to have more Catholic players. For these reasons simple conclusions as regards the Protestant-Catholic mix in. sport in. Northern Ireland are untenable.

2.3.5 - Conclusions

The information provided by sports which were included in the sample survey seems to suggest the following conclusions. People who take part in organised sport appear more likely to be middle-class, much more likely to be male, and, to a greater or lesser degree dependent on the particular activity engaged in, somewhat more likely to be from a younger age-group than would be the case in a typical cross-section of the population. This may be explained to an extent by the nature of the sports selected for the survey, by the lack of response of particular sports and by the limits of the very basic methodology used. However these findings may also be considered to support the view that the people who are under-represented in sport are those likely to be disadvantaged in terms of resources such as money, time, social confidence and status.

The position in respect of religion is more difficult to discern. It is perhaps understandable that sports were somewhat less forthcoming in providing estimates of their religious mix than in respect of the other socially relevant characteristics. In particular sports which appear and/or thought themselves to have a greater number of Protestants than Catholics taking part in their activity were reluctant to estimate the extent to which this is the case. This may reflect misapprehension about their sport being seen as prejudiced and a number of respondents put great emphasis on pointing out that they were non-sectarian and open to all.

However, the result is to make any general assessment of the religious balance in sport in Northern Ireland, based on the information provided, a very difficult enterprise. Perhaps what does emerge from this basic information is that Catholics do participate substantially in organised sport in Northern Ireland, but to the extent that this is done through activities organised by the GAA, the contact that arises between the two communities is likely to be negligible. In other sports there is Catholic representation to a greater or lesser degree. However the information obtained is not sufficient to allow firm conclusions to be reached as to the religious balance within these sports other than to say that the Protestant predominance found is at least equivalent to that which pertains in the population of Northern Ireland at large. For whatever reasons few sports, in terms of the number of players, actually bring Protestants and Catholics together in any meaningful sense, although Figure 15 supports the view that cycling and football may, to some extent and under certain circumstances, prove exceptions to this rule.

Last Modified by Martin Melaugh :