Centre for the Study of Conflict

Centre for the Study of ConflictSchool of History, Philosophy and Politics, Faculty of Humanities, University of Ulster

Centre Publications

[Background] [Staff] [Projects] [CENTRE PUBLICATIONS] [Other Information] [Contact Details] [Chronological Listing] [Alphabetical Listing] [Subject Listing]

Community and Conflict in Rural Ulster

by Brendan Murtagh Out of Print

COMMUNITY AND CONFLICT IN RURAL ULSTER University of Ulster

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr Dennis McCoy, Central Community Relations Unit for funding the research on which this report is based. I am also indebted to the people who responded to surveys, requests for information and who supported the conduct of the research. Finally, I would like to thank Professor Seamus Dunn at the Centre for the Study of Conflict for publishing the work. This project was supported by the European Unions Physical and Social Environmental Programme. Preface Brendan Murtaghs work on the sectarian geography and sectarian interfaces of Northern Ireland represents an important contribution to our understanding of the microsocial world of the Hidden Ulster. It adds to the growing and significant body of related geographical study pioneered by Fred Boal at Queens University and added to by Mike Poole and Paul Doherty of the University of Ulster. The Centre for Study of Conflict has been privileged to publish a two volume study by Poole and Doherty (in 1995 and 1996) of ethnic residential segregation in Belfast and in Northern Ireland generally, and we are very pleased to add this new study to our list. It is perhaps not surprising that our knowledge of the urban - and, in particular, the Belfast - version of Northern Ireland is considerably more detailed and extensive than that of the small scattered country towns and their associated hinterlands. The complex patterns of social and religious separation and integration that characterise rural life are often visible only to the insider. In addition, research that tries to map this complexity is often perceived as intrusive and threatening, and this ensures that valid and reliable data are hard to establish. Dr Murtaghs study is therefore all the more interesting in that he has managed to apply a whole set of sophisticated research tools to questions of importance about rural life. In particular he examines the nature of conflict in a divided rural community, along with issues of territoriality, how these manifest themselves, and the clearly fundamental role played by territoriality in the continuance of the conflict. Seamus Dunn

List of Tables

SECTION 1

Traditional analysis of the geography of conflict in Northern Ireland has concentrated on urban environments and, in particular, the regional capital, Belfast. Boals (1969) seminal work on territoriality set the context for studies on sectarian demography (Poole and Doherty, 1996), the process of segregation (Keane, 1990) and the experiences of enclave communities (Darby, 1986). There has been a number of locality based studies following ethnographic methodologies in rural towns and villages (Donnan and McFarlane, 1986) but the balance of empirical research has been with survey and analysis of urban communities. Moreover, the literature on rural geography, development and planning has paid scant attention to the ethno-religious dimensions to life in rural Ulster. Indeed, much of the available information on rural experiences of conflict are found in local histories (Adams, 1994), travel literature (Murphy, 1978) and poetry (Heaney, 1975). This research attempts to fill, in part, the research deficit on rural conflict and community life. It is based on a number of research questions regarding space and society in Northern Ireland and, in particular, questions whether the processes that have produced 14 peacelines in an urban context produce equivalent spatial relationships in rural areas. There is clearly no reason to suggest that the sorts of social and community processes that created brutal boundaries to sectarian space in Belfast end at the green belt, and so the relationship between spatial and cross-community relationships forms a central focus to the empirical research. The research was guided by three objectives:

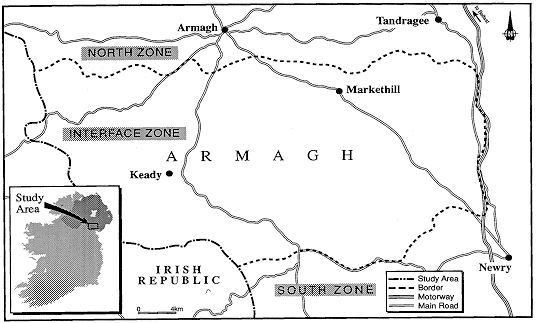

1.3 Research Design Boal has also picked up on a number of related weaknesses in research on the geography of segregation and recognised that using participant observation and exploration greatly enriches survey oriented or census approaches (Boal, 1987, p. 120) and he laments that geographers have not been notable as urban explorers (Boal, 1987, p. 120), nor as geographer anthropologists have they been prepared to live in the areas they wish to study as participant observers. Boal consistently highlights the need for new case study analysis to understand the processes of segregation and their impact on community cohesion and fracture. Drawing on this short review of methodological advice, a combination of research methods were applied within a single case study design. The selection of the study area, weaknesses of the method and steps taken to improve data quality are discussed below. 1.4 Selection of the Case Study ... sixty two percent of the rural fatal incidents which have occurred have been concentrated into six District Council Areas adjoining the border, especially Newry and Mourne, Dungannon and Fermanagh. In fact, the rate of fatal incidents per 1,000 people for rural areas is 1.38 in these six border District Council Areas but only 0.48 elsewhere in Northern Ireland (Poole, 1983, p. 175). At the second stage a focused group discussion was then held with Community Relations Officers (CROs) from these six districts together with Armagh, Strabane and Limavady (also identified by Poole as areas of high rural violence, Poole, 1983, p. 171). The aim of this discussion was to consider the nature of rural conflict, community relations and cross-community attitudes and areas of interest within each of the districts. At this stage the Newry and Mourne and Armagh District Council Areas where identified as areas for further analysis. The initial discussions showed that these areas had experienced high levels of violence, internecine conflict, population shifts between Catholic and Protestant heartlands, localised problems relating to marches and traditional festivals and problems related to segregated schooling. The final part of the case study selection process involved a further group discussion with local CROs, community activists and representatives from the Rural Development Council. This discussion attempted to draw a mental map of high conflict across the middle part of the study area. This established a centre line that would form the focus for empirical data gathering (see Figure 1.1 at end of section). The journey along this line was not designed to be prescriptive but rather to guide initial investigation, scoping communities and defining issues and areas for further analysis. The spatial concentration of urban communities in urban areas lends itself to targeted area based survey approaches. Where communities are dispersed, contact relationships are less precise and alternative spatial interactions have a more complex relationship with social processes. More investigative, less precise approaches, or what Measor refers to as rambling (Measor, 1985, p. 67) research is required. By necessity this involves the application of qualitative and ethnographic based research techniques and these have been combined within a case study design as shown below. Table 1 a shows the overall design of the research which begins at the broad spatial scale and progressively narrows to focus on the mid-Armagh case study.

Table 1a Research Methodology

Demographic analysis sets the context for more focused analysis of life in small town Ulster, a two village survey and observational research in the rural study area. 1.5 Case Study Methodology Construct validity Internal validity Table 1b Case Study Methodology

External validity A common complaint about case studies is that it is difficult to generalise from one case to another The analyst falls into the trap of trying to select a "representative" case or set of cases. Yet no cases, no matter how large, is likely to deal with the complaint (Yin, 1994, p. 37). In his approach to neighbourhood change he therefore argues that a theory or hypothesis must be tested through replications of the findings in a second or even third neighbourhood, where the theory has specified the same results should occur. Once such replication has been made, the results might be accepted for a much larger analysis of similar neighbourhoods. Given the pilot nature of this design there are inevitable weaknesses in the extent to which generalisations can be drawn from limited neighbourhood field work. Reliability 1.6 Structure of the Report Figure 1.1 Study Area

SECTION 2 2.1 Introduction The survey sampled 1050 people across Northern Ireland during October and November 1995 using random systematic sampling techniques. The urban and rural classification is based on DOE(NI) planning guidelines which categorise settlements in Northern Ireland by type and whilst this does not provide a pure system it is useful to create simple analytical categories for the purposes of analysis. 2.2 Social Distance in Urban and Rural Areas Table 2a Description of the Religious Composition of the Area (%)

Table 2b shows some degree of divergence in attitude in the main analytical categories. However, it was religion rather than location that explains variations in the data. Overall, 12% of the surveyed population wanted to live in a neighbourhood of their own religion compared to 76% who preferred mixed housing. While the proportion preferring own-religion neighbourhoods is higher for urban than rural areas, the Table shows that Protestants were more likely to prefer own religion localities. Indeed, the contrast is most marked in rural areas where 18.3% of Protestants preferred own religion neighbourhoods compared to 4.6% for Catholics. However, roughly even proportions in urban and rural areas had friends of their own religion. Seventy eight percent of urban dwellers are in this category compared to 79% for those in rural areas. Similarly, 91% of those in both urban and rural areas had friends mostly of their own religion. Table 2b Preferred Religious Composition of Neighbourhood (%)

Table 2c shows that attitudes in rural areas were more positive than in urban areas. A total of 73.6% urban dwellers defined community relations as good or very good compared to 89.7% of rural respondents. Table 2c Attitude to Community Relations (%)

2.3 Experience of Daily Life in Urban and Rural Areas The broad perception, that rural areas enjoy better community relations than urban localities, is supported by Table 2d. Most respondents (67%) felt that rural areas were less violent than urban areas. However, this is more keenly felt among the rural community (76%). Similarly, 65% of respondents thought that rural communities were more integrated and again, this was more strongly felt by rural dwellers (72%) than those in urban areas (62%). There was significant divergence between the two groups when the health of community relations was measured. Again rural respondents felt that community relations were better in their area than in urban locations but less than a quarter (24%) of those living in urban areas felt the same way. Table 2d Agreement on Issues about Conflict and Relations in Rural Areas (%)

2.4 Land and Territory Table 2e Territory and land in rural areas (%)

* Rural areas only For example, 38% of urban respondents felt that traditional parades should be allowed to march through the area of the other ethno-religious group (out-group) compared to 36% in rural areas. However, 52% of Protestants agreed with this statement compared to 20% of Catholics. Moreover, one-third (33%) of the Northern Ireland population agreed that people in rural areas do not generally sell their land to people of a different religious denomination. This was a view more widely held in rural areas (35%) than in urban area localities (32%). Most people in Northern Ireland stated that they would sell their land and property to members of the opposite religion (80%). Nine per cent said they would not do this. This was lower in urban areas than in rural localities where 16% said they would not sell to a member of the out-group. There seems to be an important contradiction in the attitudes of the rural community, in that, general measures of social distance would seem to suggest more negative practices among rural communities. 2.5 Conclusion: The Pivotal Role of Land

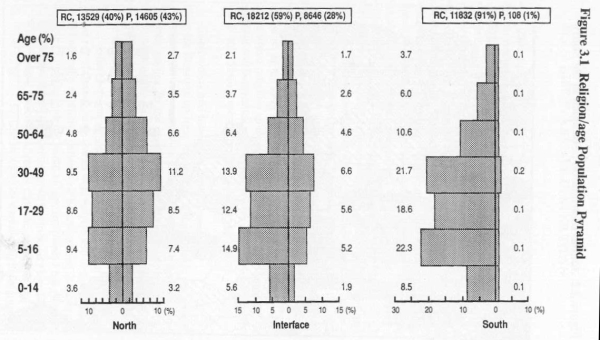

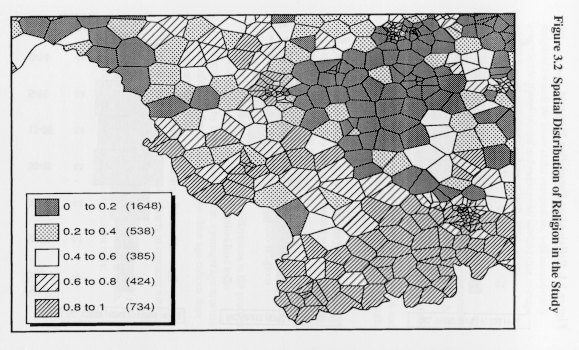

SECTION 3 3.1 Introduction General environmental pressures result, not from changes within the community, but from pressures on the community itself These pressures have been strong enough to produce enforced population movements, not because individuals have been attacked or threatened, but because the communities to which they belong have themselves become isolated and vulnerable. There are many examples of communities becoming detached from their broader religious heartlands through gradual demographic change (Darby, 1986, p. 55). Population balance is also an important conditioning factor in the type and intensity of inter-group contact and therefore behaviour. In a fascinating study of racial attitudes to school desegregation in Texas (USA), Pettigrew and Riley (1972, p. 183) noted that southern counties with a large percentage of Negroes tended to have smaller lynching rates when the size of the Negro community is held constant. This graphic portrayal of the influence of demographic balance may have important implications for Armagh where segregation rates vary considerably. A context is set for the review of the data by examining recent demographic shifts, and, in particular, rural re-population in Northern Ireland. This analysis is divided into three main parts. The next subsection looks at current population size and characteristics but focuses on the difference between the two communities and segregation at ward level. This is followed by an analysis of trends since 1971. Trend analysis at the micro spatial level is beset with problems as administrative boundaries have changed considerably since 1971. However, the analysis attempts to infer general conclusions from the available data. The final sub-section highlights some key socioeconomic differences between the two communities and profiles the area against trends at the Northern Ireland regional level. 3.2 Demography and Ethno -Religious Space Of the 20 towns whose change was analysed between 1911 and 1981, 15 experienced an increase in the Catholic share of their total population. In consequence, Protestants adjust to the threatening Catholicisation of their town by moving house just enough to ensure that they continue to live in the same kind of local environment as before (Poole and Doherty, 1996. p. 248). They compare the results of their research with that of Massey and Gross (1991) on American housing where a fundamental control on the amount of desegregation which could take place was the attitude of the white community to having a black minority in its neighbourhood and they suggest as little as 5% as a threshold. Poole and Doherty argue that analogous Northern Ireland thresholds are substantially higher in most places but that Protestant populations engage in a degree of residential adjustment. Where the Protestant community tries to maintain stability in their level of isolation, they are consciously attempting to maintain a pre -exi sting level of dominance because they wish to see either their current majority status continued, or less often, their present minority level not subject to decline (Poole and Doherty, 1996, p. 250). 3.3 Population Change in Rural Ulster considering the patterns of births, deaths and natural increase, it seems that population growth in the south and west of Northern Ireland can be attributed to a continued high rate of natural increase combined with a lessening of the rate of out-migration from the levels experienced in the 1970s (Shuttleworth, 1992, p. 87). Stockdale has detailed the process of counter-urbanisation and has identified the DCAs of Armagh and Newry and Mourne as experiencing the highest levels of rural population growth. This process of rural repopulation dates back to the mid 1970s when the distribution pattern of rapid population growth can be described as representing isolated pockets with three principal areas of concentrated growth: the border region of Newry and Mourne DCA; the Lakeland area of Fermanagh DCA and the south-west of Londonderry DCA (Stockdale, 1991, p. 76). By 1985-87 not only were these wards involved, but the previous pockets had been consolidated to produce several major axes of growth in which Newry and Mourne was one. In a positive departure from the rather descriptive nature of much of the research, Stockdale (1992) posits three explanations for rural re-population: voluntarist, non-voluntarist and intervention. Adopting a behavioural approach, Stockdale firstly emphasises the importance of human motivation and individual residential choice as a factor influencing this trend. Secondly, the importance of structural forces operating in society as a whole is stressed. Finally, and most importantly for Stockdale, intervention is seen as the factor most influencing the turnaround. In particular, she argues that the relaxation of planning controls associated with residential developments in the open countryside since 1978 is the key causal factor: removing or reducing these (planning) barriers gave way to a greater freedom of residential choice and accordingly paved the way for re-population of the Northern Irish countryside (Stockdale, 1992, p. 419). This factor will be further explored in this study but the significant point is the extent to which state intervention and the use of planning instruments can be used to control differential demographic shifts in peripheral rural areas. 3.4 Population Size and Structure Figure 3.1 (see end of section) shows that in the north zone, Protestants and Catholics are in relatively even proportions. However, the population pyramid does reveal some important distinctions between the two religions. Firstly, there are greater numbers and proportions of Catholics in the younger age cohorts. In the nortin the younger age cohorts are relatively fewer and the proportion in the older age cohorts relatively higher. In the interface zone, more than one-fifth of the population are young Catholics (under 16 years old) while young Protestants make up just 7% of the total population. Indeed, there are more Protestants over 50 years old than there are under 16 years of age. The reverse is the case for the Catholic population where 12% of the population are over 50 years old. This has significant implications for population growth in that the Catholic population has greater long term potential for renewal while the Protestant population is ageing relative to Catholic trends. In the interface zone 59% (18,212) of the population are Catholic compared with 28% (8,646) for Protestants. This numeric difference coupled with differential demographic structures adds to the vulnerability of the Protestant community. Compton and Coward have noted the wider cultural and political significance of these trends: the low fertility of Protestants is a continuation of the British demographic regime whereby Catholic fertility is significantly higher and belongs to the Irish demographic regime (Compton and Coward, 1989 p. 34). The link between the political aspirations, demography and territory is perhaps most vividly demonstrated in South Armagh. Only 1% of the population is Protestant. Moreover, nearly one third of the Catholic population is under 16 years old. 3.5 The Spatial Distribution of Religion Finally, the analysis shows the relative concentration of Protestants in the north part of the study area, particularly in the wards to the south and the east of Armagh city. While the graphic symbols of segregation in highly concentrated urban communities may be absent here, the data show that ethno-religious segregation is a significant feature of living patterns in rural communities. Given this backcloth, it would be surprising if segregation and integration did not condition inter-community attitudes and behaviour. The primary aim of the empirical research will be to explore how the two communities act out differences in a rural context. This will be strongly influenced by the changing levels of the existing balance of the population. 3.6 Trend Analysis: Border Flight? Precise changes in the religious balance of the population are possible when specific settlements are analysed and the case of Keady illustrates the relative greening of this part of Armagh. Between 1971 and 1991 the proportion of Catholics rose by 10% from 79% to 89%, whereas, the Protestant population declined from 9% to 3%. The reverse is the case in Tandragee where the Protestant population increased from 46% to 64% in the same period while the proportion of Catholics declined from 16% in 1971 to 13% in 1991. The dominant demographic trend seems to be a proportionate increase in the Catholic population in South Armagh and a proportionate increase in the Protestant population in the north of the study area. This is having a profound effect on the interface community which is experiencing these centrifugal forces first hand. This is particularly important where one community is in a minority. In most cases this will be where the minority population is Protestant, declining and displays relative ageing in the demographic structure. Population structure and change are key variables that condition inter-group attitude and behaviour. 3.7 ACORN Population Analysis Table 3a ACORN Profile of the Study Area

The main point to note from this table is the changing social structure when moving south through the study area. The dominant group is Protestants in Group 56. This is titled Affluent Rural Communities with Good Communications Links and Low Unemployment reflecting the link between that community and urban centres in north Armagh and Belfast. A smaller proportion of Protestants are in Group 10, Affluent Working Families with Mortgages which is characterised by households in the higher socio-economic classes who love buying new gadgets and appliances and are very keen to keep up to date with new technology (CACI, 1993, p. 22). Catholics in Group 58 are a feature of all areas but increase in importance toward the south zone. This Group, called Local Occupations, Some Unemployment and Large Families, is characterised by employment in agriculture, high unemployment (an average of 24%) and 22% have an average household size above six persons (CACI, 1993, p. 72). Group 57 again dominated by Catholics, is similar to Group 58 and is titled Remote Properties and Small holdings, with Employment in Agriculture and Tourism is characterised by poor infrastructure, land quality and housing standards. The final Group in Catholic South Armagh is 33 and is described as Council Areas, Some New Home Owners. The socio-economic profile of these neighbourhoods is heavily weighted towards the lower status occupations, with considerably lower levels ofprofessional and managerial workers than average and 69% more unskilled workers (CACI, 1993, p. 48). 3.8 Conclusions

SECTION 4 4.1 Introduction 4.2 Communities and Conflict in Small Town Ulster Leytons (1975) study of the small Protestant rural community of Perrin observed that its inhabitants see their village as a bastion of Protestant morality and Protestant virtue (Leyton, 1975, p. 11-12) but highlighted that in areas experiencing high levels of violence Protestants emphasised their political rather than their religious identity. Similarly, in their study of a small border village of Daviestown, Hamilton et. al. (1990) highlighted the damaging consequences for community relations of a prolonged paramilitary campaign in the area. In such a small and close knit community, the resultant deaths had had a traumatic effect, amusing suspicion and fear and leading to an almost total polarisation and lack of understanding between Catholics and Protestants ... The violence had strengthened the constraints which had always existed, leading to increased social segregation and polarisation (Hamilton et. al., 1990, pp. 54-55). In an extensive review of the anthropological literature on locality conflict, Donnan and McFarlane (1986) highlighted the significance of diverse social, kinship and ethnic cleavages in rural life. Table 4a attempts to summarise their analysis of the relationship between different cleavages in micro-societies. Kinship patterns are important in establishing new business while neighbours are more likely to be involved in sharing arrangements between farmers (Leyton, 1975). Political and religious differences are evident in the attitudes of the respective communities to their identity and self description of core values as well as the way in which local services are used on sectarian lines. In her work, Harris (1972) highlighted the common identity produced by attachment to place and the sense of ownership and pride in a local community and its long term success. Finally, Donnan and McFarlane highlighted the significance of local social structures and hierarchy based on influence and wealth which cut across kinship, religious or community bonds. Table 4a Social Cleavages in Small Town Ulster

* Based on Donnan and McFarlane (1986). Thus, Donnan and McFarlane conclude that it is difficult to say whether kinship, social class or religion is the determinant variable in explaining social relations generally and inter-group contact in particular. If people are continually switching from one identity to another from situation to situation, it becomes problematic to assign primacy to any single identity. Nevertheless, at particular times, in particular places, with particular people, some identities may be consistently more weighted than others (Donnan and McFarlane, 1986, p. 895-6). Writing from a geographical perspective, Kirk (1993) offers one approach to prioritising types of social contact by distinguishing between individual interests (for example, by sharing labour and machinery between farmers) and the group interests of preservation. In his exhaustive analysis of land transfers, he points out how Protestant and Catholic farmers accepted lower values for land by selling it within the ethnic group. Thus, he concludes, group interests are best served by the existence of social closure with an absence of land transfer across the religious divide (Kirk, 1993, p. 334). The survey presented below also suggests that anthropological studies have tended to underplay the significance of ethnic cleavages. Adams (1995) analysis of Cashel, Co. Fermanagh highlighted the danger of over-reliance on a single research design in community conflict. In this recent contribution to the anthropological literature, Adams (1995) highlighted the importance of a sense of common community in overcoming religious tension in the village, the people of Cashel "live in each others pockets ". There is such a frequency of contact that the gulfs which sectarian violence and intimidation open are so often quickly bridged (Adams,1995, p. 24). However, her report contains some significant contradictions in that it also touched on the presence of separate schooling, different sporting and social infrastructure and the exodus of Protestant families from this border region after the murder of a number of local members of the security forces. This, in part, explains some of the weaknesses in the anthropological literature for it almost always treats the community under research as a closed system unconditioned by the socio-political and economic context around them. Donnan and McFarlane recognise the limitations of research carried out in communities without an eye to events which are taking place outside the community (Donnan and McFarlane, 1986, p. 135). For example, an analysis of the attitudes and behaviour of Protestants in Oldville would be incomprehensible without an understanding of the wider demographic changes in the area and, in particular, the shift of the Protestant population away from the border. These condition attitudes which themselves affect population movements as feelings of insecurity are acted out by the people moving to more secure heartland territory. 4.3 Religion and Demographic Change in the Town Table 4b Preferred Religious Composition of Area (%)

It is difficult to reliably compare community relations attitudes in Qidville with other localities or to gauge whether rural areas are more or less integrated than urban environments. However, Table 4c compares Qidville with other areas and surveys on attitudes to integrated living. This shows that attitudes among both Protestants and Catholics are more extreme in the town than among all rural dwellers and Northern Ireland as a whole. Only people living in Belfasts peaceline zones hold more negative attitudes to the question of mixing. Again, this would at least question the hypothesis that rural communities are generally more harmonious than urban ones. Moreover, the available data suggest that the history and experience of violence and the sense of community sustainability are key determining variables explaining community attitude and behaviour. Table 4c Comparing Attitudes to People in Favour of Integrated Living (%)

1. Gallagher (1995, p. 19) The reality of demographic changes was reflected in the 61.2% of Protestants who felt that the area was becoming more Catholic compared to 32.5% of Catholics who felt that way (see Table 4d below). Only 2% of Protestants felt the area was becoming more Protestant while 34.7% felt that it had stayed the same. Catholics were most likely to feel that the religious composition of the area would stay the same (56.3%). Table 4d Perception of the Religious Composition of the Town in Three Years Time (%)

4.4 Self Perception of Identity the determination to remain distinctive and separate leads to drawing of boundaries or building of walls, to marking out territories and to a physical and emotional distancing from others (Dunn, 1995, p. 4). The consequences of these processes are lack of understanding, reinforced nationalism among respective communities and ultimately fear and suspicion. The survey revealed these processes at work in the micro-community of Oldville particularly when social distance was measured. Forty three per cent of Protestants said they would not allow a member of their family to marry a member of the out group compared to 9% of Catholics who felt the same way. As the table below shows the same trend was evident for joining clubs and societies and for integrated living. Table 4e Social Distance Measures: Would You Allow a Member of the Opposite Religion (?)

* Figures in percentages More than 14% of Protestants would not welcome a member of the out-group to live in their street or neighbourhood compared to 1.3% of Catholics in the town. Contacts at a personal level were also relatively limited. Three quarters of Protestants (75.5%) had most friends of their own religion which was roughly equal to the figure for Catholics (73.8%). This is broadly in line with the statistics for all rural areas in Northern Ireland (see Section 3). In their study on three communities in Northern Ireland Hamilton et. al. noted that, It appears that Protestants find it important to keep the demarcation lines clear, as this confirms the importance and inevitability of the conflict. At a personal level, this could be seen most clearly in Redlands, in the apparent reluctance to sell land to Catholics or to use Catholic owned commercial services' (Hamilton et. al., 1990, p. 76). Hamilton also argued that each community is unaware of its own behaviour and attitudes and this cultural blindness explains the contradictions in the survey data which show a strong perception that community relations in the town are good while at the same time showing minimum contact between the two religions and segregated use of local services and facilities. Thus they point out that an area can, overtime, be defined as Protestant or Catholic, and there is then a reluctance by the out-group to visit that area or use facilities in the area, actual threats or intimidation, while they are an important problem, are not necessary, though they may commence this process or reinforce it once it has commenced (Hamilton et. al., 1990, p. 76). These themes are reflected in the survey data from Oldville. Thus, a significant paradox in attitudes is evident in attitudes to community relations and violence. A total of 79.2% of people thought that community relations in the town were good although this was slightly lower among Catholics (77.5%) than among Protestants (87.6%). However, more than half of Protestants (53.1%) thought that the area was more violent than other areas in Northern Ireland during the Troubles compared to only 28.8% of Catholics (see Table 40. Table 4f Attitude to the Level of Violence in the Area compared to Other Areas in Northern Ireland (%)

Interviews with two Protestant community leaders suggested that this was due to the different experiences of the two groups over the 25 years of the conflict, the period of the seventies was one of fear for Protestants UDR men living in isolated areas were being picked-off and the Provos were very active - you see, were so near the border We saw our friends and relatives killed here and the people who did it or set them up are walking around free ... and cant be touched. Its very hard to talk of community relations when these people are given protection. 4.5 Contesting Territory Catholics are nearly twice as likely to feel that community relations are better in the town (41.3%) than Protestants (22.4%) (Table 4g). Moreover, the divisions are greater when it comes to the contentious issue of marching. Ninety eight percent of Protestants feel that traditional parades should have complete freedom to march in the area compared to only one-third of Catholics (33.8%). Table 4g Comparing Community Relations with Other Areas (%)

The issue of ownership of territory is also highlighted when the sale of land is analysed. Sixty one percent (61.2%) of Protestants feel that people generally dont sell their land or property to members of the opposite religion. Only 38.8% of Catholics believed this although 37.5% were not sure. In short, about one-quarter (24.5%) of Protestants and just over one-third (3 8.8%) of Catholics felt that the land market operated as a recognisable economic exchange system in the Oldville area. As Connaugton (1995) noted in his Border Diary, Property doesnt often change hands round here. Religion runs in the soil (Connaughton, 1995, p. 45). 4.6 Potential Actions Table 4h Policy and Practice Emphasis (%)

4.7 Conclusion: a Town of Paradoxes Whilst most people regard community relations as good in the town, a high proportion of people have little or no contact with the out-group, are less accommodating to the out-group than the population generally and have vastly different perceptions of violence and how conflict has affected townspeople. The primacy of rural territory is reflected in the widely heldview that sectarian cleavages significantly distort the land market in a way that protects ownership within each community. The two communities have contrasting community relations priorities. Catholics want action on policing and parades whilst Protestants regard decommissioning paramilitary weapons as crucial.

SECTION 5 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Contact and Attitudes The survey confirmed the long established attachment to place in both villages. Nearly two-thirds (64%) of people in Whiteville and half (50%) of those in Glendale had lived there all their lives. Despite this, there were comparatively few close friendship or kinship ties across the religious divide. As Table 5a shows more than three quarters (77%) of people in Whiteville had most or all of their friends and relatives of the same religion compared to 86% of people in Glendale. Table 5a Proportion of Friends and Relatives who are the Same Religion as Respondent (%)

There is a sharp contrast in the perceptions of respondents when attitudes to community relations within, and between, the villages are examined. Table 5b shows that community relations in the two villages are perceived to be good. In Whiteville, 84% described relations between the two communities as either very good or quite good. The figure for Glendale was 93%. However, only 45% of people in Whiteville and 29% in Glendale felt that community relations between the two villages could be described in that way. Indeed, more people in Glendale (36%) described community relations with Whiteville as poor rather than good. It will be shown latter how these differences in attitude are conditioned by recent experience and fear about the long term sustainability of the Protestant population of the village. When prompted for specific explanations of this pattern some of the more incisive comments rooted the cause as a lack of contact with village neighbours: there is no real reason to mix with each other (Whiteville resident). We have no reason to go there and they have no reason to come here (Glendale resident). One other respondent commented that we have probably found ways of not meeting and mixing (Whiteville resident), highlighting the importance of avoidance as a key variable in community relations attitudes and patterns of segregated behaviour. Table 5b Attitudes to community relations within and between the villages (%)

The lack of contact is borne out by the statistics, as almost two-thirds (64%) of people in Whiteville said they never visit Glendale. The picture is slightly more complex for Whiteville as residents are more likely to travel through Whiteville to access other transport and service centres. Even here, however, 29% of villagers said they never visit Whiteville. Attitudes to the future religious composition of the villages also reveal interesting contrasts. As Table Sc shows, half (50%) of the residents of Glendale wanted the area to remain all or mostly comprised of people of the same religion as themselves. Thirty six percent stated that they would prefer to see the village religiously integrated. In Whiteville however, 62% of residents said they would like to see the village mixed although a sizeable proportion (29%) wanted the dominant balance of the Catholic community maintained. Table 5c Attitudes to the Future Composition of the Village (%)

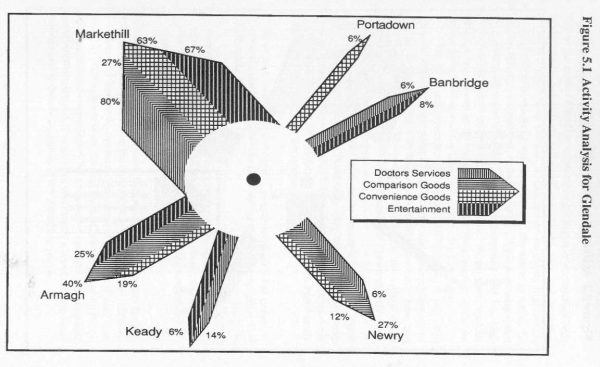

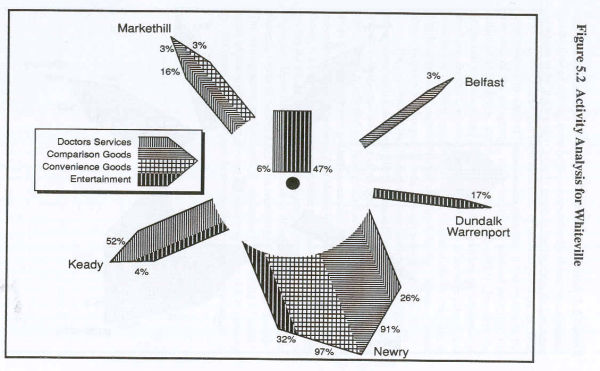

5.3 Activity Analysis The residents of Glendale mainly look North to largely Protestant urban towns such as Armagh, Markethill and Portadown for comparison goods, convenience goods and services. It is interesting that more people go to Markethill for these goods than Newry despite the latters more dominant hierarchical settlement status offering a wider number, range and quality of services than Markethill which, while three miles closer, is a smaller order settlement in the sub-region. When the activity profile for Whiteville is examined (Figure 5.2) an almost mirror image emerges. Here the main population is drawn South to the mainly Catholic towns of Newry, Keady and even across the Border to Dundalk. The demographic analysis and in particular the greening of border areas explains part of the process but close inspection of local history reveals more immediate push factors on the Protestant population.

5.4 Death of a Village? The first major incident occurred in 1976 during a period of sectarian murders, high paramilitary activity and a strengthening of security force presence with the development of an Army base two miles from the village. The main employment in the village was a small textile factory whose labour force was drawn mainly from surrounding towns and villages. After a period of tit-for-tat sectarian murders in the area, 10 of the employees (all male and Protestant) were taken from the works bus and shot dead three miles outside the village. All the victims came from the nearby town of Bessbrook but the impact on community relations in Glendale was devastating. Everyone remembers the night ... people were afraid to come out in the dark or answer the door unless they knew the caller (Glendale resident). Someone in this area living here set these men up. They had to know who was on the bus and where it went ... these are people who we probably meet every day and who pass the time of day as natural as you like (Glendale resident). Speculation about the role of local nationalists in the murders fuelled sectarian fear and in particular the feeling of the enemy within,, difficult to define and harder to censure cumulated the sense of fear and insecurity. The murders were claimed by the Catholic Reaction Force who have claimed responsibility for a number of murders of Protestants across Northern Ireland. The incident was clearly a benchmark in local relations and is deeply ingrained in the Protestant psyche: things were never the same after that ... how could they be? (Glendale resident). Another violent attack, a bomb rolled into the local UDR base (mentioned above), killed three soldiers and destroyed the base which never re-opened. The attack on basic security as well as the economy of the village was acutely felt by the Protestant community: as well as providing jobs and money in the area, the end of the base meant there was no Army between here and the border (sic) (Glendale resident). The sense of physical and psychological exposure, the location of the village in wider territory and the implied fear seemed very real after the base closed. All of this had a knock on effect on local commerce and in the early 1 990s the post office and local grocery shop both closed and what passed for the commercial core of the village fell into physical neglect. As noted previously census data showed that the Protestant population is declining, ageing and, with fewer numbers in the younger age cohorts, it has less opportunity for self-renewal. In contrast the local Catholic population is characterised by higher than average household sizes; 3.7 for Catholics compared to 3.0 for Protestant households in the area, more people in the younger age cohorts (21% for Catholics compared to 7% for Protestants) and equal proportions in the age range 65 plus (6 % compared to 5% for Protestants). These demographic trends have had an impact on the local Primary school which closed in 1995 and the remaining pupils were bussed to a school five miles away. A community activist was well aware of the implications of closure for the village: If a village has a school then it is the centre for things - it has status. When the school goes why would young families want to stay never mind return (Local community leader and former elected councillor). Finally, the local orange hall was destroyed by fire in the same year. Indeed 4 out of 5 Orange halls in the area had been attacked from mid-1994 to the end of 1995. As a pivotal socio-cultural institution the practical and emotive implications were again well recognised: this was an attack, not just on a building, but on a people (Glendale resident). 5.5 Conclusions: the End of Critical Mass? the absolute size of a particular population group is a critical factor in the development and maintenance of the group as a cohesive entity. Sheer size enables a range of institutions to be supported, the institutions in turn providing coherence and an inward focus for the group (Boal, 1987, p. 116). The short review of conditions in Glendale seems to suggest that a dual force is at work. At one level the critical mass is being eroded as the population has declined naturally and, at another level, institutions are being fundamentally attacked in a way that is having a detrimental impact on self-perception of group critical mass. It is interesting to note that residents in Glendale felt strongly that the village was becoming increasingly Catholic. It is the vicious interaction of these forces, each feeding from the other, that has most serious implications for the long term sustainability of the population of the village.

SECTION 6 6.1 Introduction Group interests are best served by the existence of social closure and an absence of land transfer across the religious divide (Kirk, 1993, p. 334). In an exhaustive study of land transfers in Glenravel ward, Co. Antrim, between 1956 and 1987, Kirk showed how maintenance of land ownership patterns involved limited seepage (p. 367) between dual land markets in the area. The duality of the land transfer system is analysed through case study material in this section. Kirks empirical analysis sets the context for the description of one exchange of a farm in the study area called, for the purposes of this paper, Pine Hill. The instruments operating dual and often symmetrical land exchange systems are described and some outline comparisons with analogous urban systems suggested. The core of the section is a discussion of the implications of rural territoriality for community relations practice at the micro-spatial scale. 6.2 Dual Land Markets: Preliminary Evidence In short, ethno-religious cleavages are the key determining variable when attitude to land and retention of territory is assessed. Preliminary interviews with local community leaders supported the operation of similar processes restricting land transfer in Armagh. It has happened in the past but you rarely see it now (local community leader). Table 6a Land transfers between Protestants and Catholics in Glenravel Ward 1958-1987

* (Source, Kirk, 1993, p. 496) I am not saying that it doesnt happen, it is just not done in the area ... it would not be acceptable (local church-man). This latter point is significant because it suggests a measure of outside control on land exchange. Reports of threats, abusive phone calls and, what one interviewee referred to as, friendly advice are all used to ensure that land stays within a particular ethno-religious group. While all of this is difficult to verify empirically, it is clear that some element of control is used. One Protestant interviewee revealed how he inherited a farm from a relation but as he lived and worked in Belfast he wanted to sell it quickly at the best price. The interviewee received what he clearly perceived to be threatening phone calls urging him not to sell to a Catholic. (The farm was sold to the highest, and in this case, a Protestant bidder). The system of land exchange in rural Northern Ireland seems more complex than in urban locations. There are definable gatekeepers, principally, the auctioneer, solicitor and to a lesser extent the estate agent. Often there is a Protestant property infrastructure and a Catholic infrastructure each serving the respective communities. However, behind the scenes negotiations at a personal level characterise their style of mediation in land exchange in rural areas. Because the system is closed and not open to public scrutiny, suspicion and rumour about corruption and sectarian practice have room to grow. In some cases this has lead to intense and long standing bitterness over the sale of individual property. 6.3 The Battle for Pine Hill The property was on the market initially for 9 months during which three bids, all from Catholics, could be identified in the research. The respondents complained about delays in the response to their bids, lack of information and lack of access to the selling agent. Those interviewed remained convinced that, because they could be identified as local Catholics, the solicitor deliberately placed obstacles in their way. Each applicant was informed that their bid was inadequate and the property was taken of the market for a year. One of the applicants believed that he had offered above the realistic local value for the property because he wanted the farm for his son who was intending to get married and stay in agriculture. The applicant, a local farmer then explained that the next he knew of the farm was that it was sold to a Protestant farmer with a large farm in the area, The respondent was convinced that the land was taken of the market until one of theirs could be found to buy it. He noted that the sale was not the product of open negotiation. In the case study most evidence related to the retention of Protestant land and protectionism from potential Catholic buyers. This has caused some problems for the local rural economy. In the County Armagh area the Catholic population is growing, has a younger age structure and has higher than average household size. The demand for agricultural land to provide employment for the children of Catholic farmers is increasing. The inability of the land exchange system to release land in response to demand has, some community leaders would argue, resulted in inefficient and uneconomic farming, loss of population and often intense family friction due to competition for scarce land resources. This problem has to some extent been eased by the process of letting land through the conacre system. This system involves leasing fields on a long terms basis to individual tenants and it highlights some of the contradictions revealed in the survey data. While Protestant land owners are reluctant to sell their land to Catholics they will let their land on long leases and this further extends to sharing machinery and labour at peak times of the agricultural year. 6.4 Cross-Religion Sharing Social relationships can also be found in labour and machinery exchange between farmers. There was a degree of pride among those interviewed in the system of mutual help and support among the farming community. The lack of monetary exchange, mutual friendship and shared interest in weather, European Union grants or the effects of BSE bond farmers in a meaningful and clearly sincere way. While the land exchange system does not work effectively, trading in stock and produce operates as a recognisable market. Markets or local marts are places to buy and sell livestock but they are also a setting for social interaction between farmers. In these environs religion plays no significant part in exchanges either social or economic. The farming issues dominate and the distinctive farming culture is obvious in mart life. There is a sense of overt satisfaction in the way religion plays no part in such relationships: nobody ever mentions religion here ... we do business., and if youre a good man and honest - thats what counts (Farmer in the Keady area). 6.5 Discussion one way to increase peace might be to "de-territorialise" identity issues. When an issue is delinked from territory (i.e. its demands are not tied to controlling a piece of territory), then it is likely to produce war, even though it may generate conflict if territorial issues can be de-coupled from other issues, the probability of violence will drop considerably (Vasquez, 1995, p.289-290). One of the central features of the empirical research has been the extent to which territory can not be de-coupled from community relations and contact in the study area. Control and ownership of land is the pivotal defining feature of the Northern Ireland conflict. Maintaining territory involves a complex interaction with the local market system, closed negotiation, influence over key agents in that system and at times, intimidation of both seller and buyer. In Belfast, territorial boundaries are sharpest and segregation most intense in public sector housing. The highly regulated system of public sector housing planning, development and allocation facilitates the maintenance of ethnic geography. The Housing Executive have rarely attempted to redraw long established territorial boundaries and respect for the territorial imperative has helped to diffuse violence in contentious areas of the city (Murtagh 1994). In rural areas the private exchange system which involves a small number of key gatekeepers takes on crucial importance. The potential of these gatekeepers for independent action is limited in the same way as the Housing Executive in Belfast have limited potential to re-draw an ethnic map that has less to do with ownership of parcels of land and more to do with the way that ownership expresses the legitimacy and permanence of ethic identity. Recognition that territory, and how it is protected, is a feature of day to day interaction between the two communities emphasises the need for more realistic strategies to manage conflict at a strategic and local level. Approaches that ignore deep structural factors in the configuration of the Northern Ireland conflict will have limited currency. In a comprehensive review of community relations projects at District Council level, Knox (1994) divided activity into five types, only one of which involved what he called focused community relations aimed at tackling, head on, controversial community relations issues. This approach suggests that such issues, if left unresolved, compound insidious sectarianism and bigotry (Knox, 1994, p. 603). The other categories relate to the funding of high profile events such as festivals; mainstream community development work; cultural traditions that reinforce the identity of each tradition; and substitute funding, through which community relations resources are used to fund projects that would have been supported anyway. The District Councils Community Relations Programme for Newry and Mourne emphasised the role of reconciliation and festival based events, 'most of the cross-community relations projects are based on community events such as festivals, a local "hiring fair" and a concert at Christmas (Community Relations Officer). The Community Relations Officer points out that it is difficult for community relations work to get beyond local religious divisions which often run deep and have been sustained over a relatively long period of time. Therefore, community relations activity in the District has centred around the softer issues where contention and conflict are unlikely to surface or be addressed. In broad terms Bloomfield (1995) locates this type of work within resolution theory. In short, this approach is, subjective, relationship-based, needs-based, comprehensive, aiming to remove or transform the roots of conflict through joint analysis and co-operative problem solving. A third party takes a non-directive, facilitative role to help the conflicting parties redraw their relationship co-operatively around a mutual problem in order to generate a self-sustaining, integrative resolution (Bloomfield, 1995, p. 153). On the other hand, the settlement approach is, objective, issue-based, power-based, pragmatic aiming at reduction in conflict through negotiation and compromise ... Settlement prides itself on its pragmatism in aiming at the achievable, and questions the scope of the approach demanded by resolution (Bloomfield, 1995, p. 153). The empirical research presented here suggested that the reality of conflict at the local level requires a more realistic and pragmatic response than that offered by initiatives predicated on an analysis that suggests resolution is a realistic alternative. Hard issues, such as the system of land exchange and its role in reinforcing territory, need to be understood and addressed. They are not reducible to resolution based measures that characterise much of community relations activity in Northern Ireland. Centuries old practices and beliefs are locked into the rural socio-cultural and economic system and to talk about resolving them is to miss the complexity of the conflict and how it is acted out in small communities every day. The best we can hope for in the short-term is to minimise their negative consequences and to hope for settlement of contentious territorial issues at the micro or local level. 6.6 Conclusions

SECTION 7 7.1 Introduction 7.2 Territoriality and the Process of Residualisation For example, the research identified a number of communities experiencing decline related to selective exiting of its younger and more able members. In places such as Protestant Glendale, direct and perceived threat has had a cumulative effect on community relations attitudes. These are best expressed in the activity segregation between it and Whiteville, in that, the Protestant village oriented itself north for services and facilities, whilst the Catholic village looked south to Catholic towns to serve their needs. The sale of land and the asymmetrical institutional infrastructure that supports in-group sale, highlights the way in which territory is ingrained into social and economic as well as physical aspects of life in rural Ulster. The establishment of a review body on parades in Northern Ireland was an illustration of a macro-level response to a crises territorial issue. However, by focusing on the parades issue specifically, the scope of the inquiry is limited to only one of a number of related manifestations of territoriality. Shop boycotts, church demonstrations, traditional parades, avoidance behaviour and the experiences of residual communities are all aspects of territory which run central to the Northern Ireland conflict. An opportunity was perhaps missed when, instead of commissioning a single issue review, a government supported standing commission on territory was not constituted to review all aspects of territory, its impact on community relations and the potential role played by a wide range of policy actors, As the empirical analysis illustrated, the control and ownership of territory is one of the clearest expressions of the nature of conflict and division and needs to be researched, analysed and responded to in a comprehensive manner. Such a commission, could embrace a wider set of interests than the parades review body and could undertake further analysis of the issues and relationships between territorial behaviour, its consequences for communities and possibly agreed principles about the use, of and respect for, group territory. As well as providing a framework for research, analysis and discussion, such a commission could sponsor pilot projects to explore best practice to a range of territorial related issues and problems. 7.3 Policy Implications

The Discussion Paper goes on to recognise the need to move beyond land use planning (DOE (NI), 1996, p. 3) and to view the city as a complex socio-spatial system where the consequences of sectarian division should be a primary policy concern. This has resonance in recent literature on planning theory and practice. Heffley, for example, argues the need for planning to explore what is relevant as defined by individual communities and to recognise the power of argument and negotiation in resolving land use problems,

She encourages the use of negotiation counsels to encourage individuals and groups to articulate their interests together in an environment where interaction is not simply a form of exchange or bargaining around predefined interests but is a genuine dialogue between competing interests. In Northern Ireland, the need to locate community relations issues at the centre of such a planning dialogue is crucial. This has implications for planners as well as community relations practitioners. A fusion of the substantive understanding of socio-spatial dynamics, area degeneration and demographics with conflict negotiation and mediations skills is an important training challenge. For example, Healey recognises the implications of community dialogue for traditional planning research skills,

Donnan and Mc Farlanes work shows how ethnographic methodologies can be powerful in unpacking communities and the tensions and conflicts laden in their daily activity and interaction. The perspectives of the people of Glendale on what might help regenerate their village must be preconditioned by an understanding of the different demographic histories of the two communities and the sustained decline of the Protestant population in particular. Helping marginal communities to articulate their concerns in a way that will impact on the prospects for maintaining a viable and sustainable future is a key challenge for both community relations practitioners and planners. June Manning Thomas (1994) has made a similar call for the role of planning in responding to the problems of marginal black inner city communities in the United States,

Recalling Friedens argument to extend planning beyond the physical environment Thomas argues the need for comprehensive community action on ill-health, poor housing, drug abuse, low self esteem and economic desperation (Thomas, 1994, p.7). Those acting on such an agenda will face formidable obstacles, not least the professional value system of planners and administrators. Hoch recognises this in the context of planning and race,

Likewise Peach emphasises the policy implications of deeply segregated communities in a Northern Ireland context, while ghettos should be unacceptable to planners, it seems to me that we should be more tolerant of ethic cities. Encouraging ethnic areas without creating ghettos is the challenge of the 1990s but we need to know more about the dynamics of choice, the dynamics of interaction and the consequences of social engineering (Peach, 1996, p. 149). Mention has already been made of the inclusion of sectarian realities in local planning strategies including the Belfast sub-regional planning discussion document. The DOE (NI) Planning Agency has introduced training on Community Relations and Planning for all its staff, recent consultation documents on strategies to tackle deprivation in Belfast and Londonderry have highlighted the problems of territoriality in community regeneration and local Partnerships created under the Peace and Reconciliation Programme have built concerns about segregated areas into their action plans. 7.4 Community Relations

A spatial focus on, what in community relations terms, would be the most serious cases - those feeling forgotten, abandoned and powerless - would seem logical for the community relations practitioners. Developing relevant practice in these areas would add greatly to the emphasis in planning on addressing problems through argument, dialogue and interest mediation. The failure to gel the related discipline in that way could marginalise community relations practice in a way that diminishes its relevance. Gallagher quotes the first chair of the Community Relations Commission in terms of its narrow policy brief.

7.5 Conclusions The potential role of a commission to address the issue of territoriality, how it is manifest at the micro-spatial scale and the relationship between events at locality level and the nature of conflict. Territory is clearly fundamental to the nature of conflict and the need to respond with comprehensive policy measures, particularly in the field of area planning and rural regeneration initiatives is vital to the sustainability of marginalised communities. Policy initiative alone can not address the problems of residual communities and the need for community relations practitioners to engage, articulate and positively approach their problems is equally important.

Adams, L. (1995) Cashel: A Study in Community Harmony, Cashel, Cashel Community Development Association. Blacking, et. al. (1978) Situational Determination of Recruitment in Four Northern Irish Communities, SSRC, British Library. Bloomfield, D.(1995) Towards Complementarity in Conflict Management: Resolution and Settlement in Northern Ireland, Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 32, No. 2, pp.151-164. Boal, F. (1969) Territoriality on the Shankill-Falls Divide, Belfast,Irish Geography, Vol. 6, pp. 30-50. Boal, F. (1987) Segregation, in Pacione, M. (ed.) Social Geography: Progress and Prospects, London, Croom Helm. Breton, R. (1964) Institutional Completeness of Ethnic Communities and the Personal Relations of Immigrants ,American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 70, pp.193-205. CACI (1993) ACORN User Guide, London, CACI. Compton, P. (1995) Demographic Trends in Northern Ireland, Belfast, Northern Ireland Economic Council. Compton, P. and Coward, J. (1989) Fertility and Family Planning in Northern Ireland, Aldershot, Avebury. Connaughton, 5 (1995) A Border Diary, London, Faber and Faber. Darby, J. (1986) Intimidation and the Control of the Conflict in Northern Ireland, Dublin, Gill and Macmillan. Darby, J. (1991) Whats Wrong With Conflict, Occasional Paper No.3, Centre for the Study of Conflict, University of Ulster, Coleraine. DOE (NI) (1996) The Belfast City Region. Towards and Beyond the Millennium. A paper for Discussion, DOE(NI), Belfast. Donnan, H. and McFarlane, G. (1983) Informal Social Organisations, in Darby, I. (ed.) Northern Ireland: Background to the Conflict, Belfast, Appletree Press. Donnan, H. and McFarlane, G. (1986) You Get on Better With Your Own: Social Continuity and Change in Rural Northern Ireland, in Clancey, P., Drudy, S., Lynch, K. and 0 Dowd, L. (eds.) Ireland: A Sociological Profile, Dublin, Institute of Public Administration in association with the Sociological Association of Ireland. Dunn, S. (1995) The Conflict as a Set of Problems, in. Dunn, S. (ed.) Facets of the Conflict in Northern Ireland, London, St. Martin Press. European Union (1995) Special Support Programme for Peace and Reconciliation in Northern Ireland and the Border Counties of Ireland, EU, Brussels. Fischer, C. (1976) The Urban Experience, New York, Harcourt Brace. Gallagher, A. (1995) Community Relations, in Breen, R., Devine, P. and Robinson, G. (eds.) Social Attitudes in Northern Ireland, Belfast, Appletree Press. Gallagher, A. (1995) The Approach of Government: Community Relations and Equity, in Dunn, S (ed.) Facets of the Conflict in Northern Ireland, Macmillan, London. Hamilton, A., McCartney, C., Anderson,T. and Finn,A. (1990) Violence and Communities, Centre for the Study of Conflict, University of Ulster, Coleraine. Harris, R. (1972) Prejudice and Tolerance in Ulster: A Study of Neighbours and Strangers in a Border Community, Manchester, Manchester University Press. Healey, P. (1992) Planning Through Debate, Town Planning Review, Vol. 38, No. 2, pp, 143-162. Heaney, S. (1975) North, London, Faber and Faber. Hoch, C. (1993) Racism and Planning, Journal of the American Planning Association, Vol. 38, No. 4, pp. 45 1-460. Keane, M. (1990) Segregation Processes in the Public Sector, in Doherty, P. (ed.) Geographical Perspectives on the Belfast Region, Geographical Society of Ireland. Kirk, T. (1993) The Polarisation of Protestants and Roman Catholics in Rural Northern Ireland: A Case Study of the Glenravel Ward, Co. Antrim, 1 956-1 988, Unpublished PhD Thesis, School of Geosciences, Queens University Belfast. Knox, C. and Hughes, J. (1994) Policy and Evaluation in Community Development: Some Methodological Considerations, Community Development Journal, Vol. 29, No. 3, pp. 239-250. Knox, C. (1994) Conflict Resolution at the Micro-level, Community Relations in Northern Ireland, Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 38, No. 4, pp. 595-619. Leyton, E. (1975) The One Blood: Kinship and Class in an Irish Village, Social and Economic Studies, Memorial University, Newfoundland. Massey, D. and Gross, A. (1991) Explaining trends in racial segregation 1970-1980, Urban Affairs Quarterly, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 13-35. Measor, L. (1985) Interviewing: A Qualitative Research Strategy, mR. Burgess (ed.) Strategies in Qualitative Research : Qualitative Methods, London, Falmer Press, pp. 55-77. McFarlane, G. (1978) Gossip and Social Relations in a Northern Irish Village, Unpublished PhD Thesis, Department of Anthropology, Queens University Belfast. Murphy, D. (1978) A Place Apart, London, Penguin. Murtagh, B. (1994) Ethnic Space and the Challenge to Landuse Planning: a Study of Belfasts Peacelines, Research Paper No.7, Centre for Policy Research, Jordanstown, University of Ulster. Murtagh, B. (1994) Land Use Planning and the Challenge to Landuse Planning: A Study of Belfasts Peacelines, Research Paper No.7, Centre for Policy Research, Jordanstown, University of Ulster. Peach, C. (1996) The Meaning of Segregation, Planning Practice and Research, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 137-150. Pettigrew, T. and Riley, R. (1972) Contextual Models of School Desegregation, in King, B. and McGinnes, E. (eds.) Attitudes, Conflict and Social Change, New York, Academic Press. Poole, M. (1983) The Demography of Violence, in Darby, J. Northern Ireland: The Background to the Conflict, Belfast, Appletree Press. Poole, M. and Doherty, P. (1996) Ethnic Residential Segregation in Northern Ireland, Centre for the Study of Conflict, Coleraine, University of Ulster. Saunders, P. (1990) A Nation of Home Owners, Unwin Hyman, London. Shuttleworth, I. (1992) Population Change in Northern Ireland, 1981 1991: Preliminary Results of the 1991 Census of Population ,Irish Geography, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 83-88. Stockdale, A. (1991) Recent Trends in Urbanisation and Rural Population in Northern Ireland, Irish Geography Vol. 24, No. 2, pp. 70-80. Stockdale, A. (1992) State Intervention and the Impact of Rural Mobility Flows in Northern Ireland, Journal of Rural Studies, Vol. 8, No. 4, pp. 441-421. Stutt, C. (1996) University of Ulster, Northern Ireland Economic Research Centre, Giplen Black and Social Information Systems Baseline Study for the Special Programme for Peace and Reconciliation in Northern Ireland and the Border Counties of Ireland, Belfast, Department of Finance and Personnel, European Division. Thomas, J. M. (1994) Planning History and Black Urban Experiences: Linkages and Contemporary Implications, Journal of Planning Education and Research, Vol. 14, pp, 1-11. Tutt, N. (1994) A Review of Community Relations Research in Northern Ireland, Knutsford, Social Information Systems. Vasquez, J. (1995) Why do Neighbours Fight? Proximity, Interaction or Territory, Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 32, No. 3, pp. 277-293. Yin, R. (1994) Case Study Research, London, Sage.

Last Modified by Martin Melaugh : | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||