CAIN Web Service

Politics in PublicFreedom of Assembly and the Right to Protest

Parading has been a feature of Canadian political life since the first half of the nineteenth century when Protestant and Catholic emigrants from Ireland began to organise regular commemorations on the Twelfth of July and later on St Patrick's Day. Toronto was the heartland of the Orange Order in Canada, the Order exerted considerable influence in local politics and the Twelfth parades were large and impressive events (Kealey 1988). Today the Order is no longer the powerful institution it once was, but it still holds a number of local church parades each year and parades through the city centre on the Saturday nearest the Twelfth. Nowadays many of Canadas varied ethnic communities also use parades to celebrate their cultural and political identity in the city and over four hundred parades are held each year in the Metropolitan Toronto area. Many of these are small localised church parades organised by diverse Roman Catholic and Orthodox communities but some, like the West Indian Caribana, have become major events which draw tens of thousands of people onto the streets. In the nineteenth century violent clashes and rioting regularly followed both Orange and Green parades and celebrations, but such disturbances have long since ceased (Cottrell 1993; Kealey 1988; Toner 1989). In recent years parades and demonstrations have not been a major source of public order concerns. The right to freedom of assembly is guaranteed by the Canadian Constitution, and while there are disputes over matters of the rime, place and manner in which parades might take place these are normally resolved informally and peacefully. Rights and Freedoms The right to freedom of assembly is guaranteed under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms which is constituted as Part I of the Constitution Act of 1982 (Knopff & Morton 1992; Mandel 1994). The Charter sets out four Fundamental Freedoms, which apply to everyone.

These fundamental freedoms are deemed to be guaranteed subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society (S.1). However, the Constitutional limits of the freedom of assembly set out in the Charter have yet to be tested in the Supreme Court. The police have a responsibility both for ensuring that the fundamental democratic freedoms are applied to all and also for maintaining public order. These potentially conflicting responsibilities might on occasion result in a restriction of basic freedoms, however a recent report argued:

There is obviously a question mark over how possible it is to adhere to this ideal. While the police have the power to invoke concern for public order in order to restrict the right to parade, it is also clear that a balance must be maintained between the competing interest groups in any area. Despite localised concepts of tradirionality (grandfathering), parade organisers have to adapt to changing social, political and economic circumstances. In practice organisers are usually ready to discuss points of contention with the relevant police department in order to reach accommodation and thereby avoid more serious disputes. Policing Parades in Toronto Organisers of parades must apply to the Police Services Board for a permit. This is usually no more than a formality and normally is readily adhered to, although some left-wing groups refuse to apply on principle. Parades that are held without a permit amount to only a small number of the total, and in general the police do not take any action against the organisers of such events. Permits should be applied for at least twenty-one days in advance, but this is taken as a loose guide. The police are often notified of small parades only a few days in advance, while they feel that larger parades require at least five or six weeks to administer and organise. This is rarely a problem, as small parades require little policing, while the dates of the larger events are well known. The Orange Order told us that they notify the police of their plans for the coming year in January, well before the legal deadline. Because the dates for the main events vary little and are well known, the police are often pro-active in planning for them. An officer from the Community Policing Support Unit is responsible for co-ordinating matters and where possible meets with parade organisers well in advance to ensure potential problems are sorted out early. This practice is maintained at the event itself: officers with experience in dealing with public events and crowd dynamics are used where possible and emphasis is given to keeping communication open with the organisers to ensure any problems are dealt with quickly. In practice the police are able to impose a variety of constraints and restrictions on parades. These usually relate to the proposed route or to the time of the event. Most restrictions aim at maintaining a free flow of traffic and avoiding disruption to business activities - there is an underlying fear that businesses might sue if a parade could be seen as causing loss of trade. Parades are therefore kept to one side of the road and away from streetcar routes. Right turns are preferred in order to avoid crossing the flow of traffic but parades are not permitted to complete a square on their route because this could block off areas and freeze commercial access. Similarly the police prefer parades to take place on a Sunday because this causes less disruption, but they also accept that as the aim of many parades is to get publicity or media attention the organisers expect the parade to take place on a weekday. Besides the obligation to facilitate the expression of fundamental rights, the police are concerned with the cost of policing the parades. All parades are expected to run according to schedule, and particularly to depart on time. This is so that the police can deploy officers both efficiently and economically and to minimise disruption to traffic. Furthermore, if the aim of the parade is to raise money, then the organisers are expected to pay for the costs of the policing. One implication of these economic concerns is that the police encourage the parade organisers to accept as much responsibility for the event as is practical, thereby minimising the demand for police time and resources. The organisers are expected to notify residents and commercial interests of their plans, they are expected to provide identifiable marshals and they are encouraged (although not legally required) to take out insurance in order to cover themselves against unforeseen occurrences for which they might be sued. Grandfathered Parades About thirty five of the parades in Toronto, including the Twelfth, the Carabana, the St Patricks Day parade, the Sikh Khalsa parade and the Santa Claus parade, are regarded as grandfathered. This gives the organisers a prioritised right to hold their parade on a specific day. However it does not create a sense of total sanctity around the event, the route might still be changed and other conditions imposed if necessary. For example, the Carabana parade is one of the largest events in Toronto, but has also ebbed and flowed in scale since it began in 1967. Although violence has only occurred in one year (1985), the police have become increasingly concerned with the potential for disorder as tensions have increased between their officers and black people.

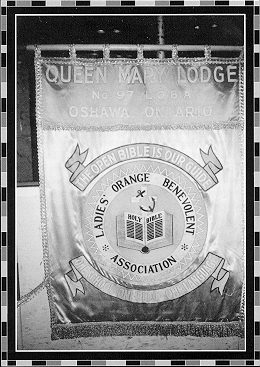

One of the results of the recent growth of the Caribana procession and the police concern with public order has been that the route of the parade has been changed on a number of occasions. Some of these have been quietly accepted by the organisers, while others have been the subject of heated negotiation (Jackson 1992:140). Nevertheless in the end the police have been able to impose their preferred route on the parade. The event now finishes in a large park where the crowds are more easily controlled. Similarly the Orange Order have changed the route of their Twelfth of July parade through Toronto over the years. Norman Ritchie, General Secretary of the Orange Order in Canada, said that when the organisation was at its peak, in the 1930s, the parade used to bring the city to a halt. But as the membership has declined and aged and the influence of the Order declined so the route has changed. The parade is now held on the Saturday nearest the Twelfth, the route has been considerably shortened and there is no return parade. The Order itself now sees the Twelfth as a family day out. It has no political overtones and a picnic has replaced the platform speeches of some years ago. The police now regard the Twelfth parade as a relatively small and unproblematic event, which needs few officers and poses little concern. It now survives as something of a contrast to the steadily growing Caribana celebrations, which generates growing problems with illegal beer sellers and excessive consumption of alcohol. The police try to restrict illegal sales and confiscate the alcohol but it remains a difficult issue each year. Conclusions The right to parade and demonstrate is guaranteed by the Canadian Constitution and this seems to be accepted with little contention. There have been no cases where parades organised by one ethnic group have been challenged by another ethnic group in recent years, or violent outbursts at any major events. However in part this seems to be because the police are able to exert a degree of control over the conditions in which a parade takes place and the organisers are expected to be responsive to the changing circumstances of the city. The Gay Pride parade is a final example of the way in which parading has been addressed in Toronto. The police noted that in the early years the Gay Pride parade was often confrontational and disruptive. But over time the route has been changed, the organisers have toned down some of the excesses, while the police have begun to address the way in which their officers treated the participants. The event has been part of the process by which a Gay identity has become established as a legitimate part of the wider society, but the organisers have also had to be responsive to the concerns of the wider community. The police now regard the Gay Pride parade as a successful community event. While the right to demonstrate is an important civil right, in practice it is not seen as having a priority over the rights of others. In particular, parades are not allowed to disrupt the commercial life of the city too much. They are allowed to take their place within the social fabric of the city but not to dominate the lives of others. As an extension, the various parades organised by the numerous ethnic communities are held either within the commercial centre or within specific residential areas. Parades have not been allowed to be used to stir ethnic conflict. Despite these apparent constraints on the freedom to assemble and parade, this has not become a contentious issue in Toronto.

Democratic Dialogue {external_link} |