CAIN Web Service

Politics in PublicFreedom of Assembly and the Right to Protest

Disputes over parades and demonstrations have not been a persistent factor in recent Irish social life. However, they have been cause of serious public disorder on a small number of occasions. Following partition in 1921 there were a number of disputes over Orange parades in the border counties and in the 1930s Eamon de Valera was sufficiently concerned about the growth of IRA activity to declare the organisation unlawful and their commemorations and assemblies were banned or constrained (Jarman & Bryan 1998). In 1939 the Offences Against the State Act which allows widespread restrictions on public assemblies was passed. More recently the two occasions at which serious disorder has broken out in Dublin resulted from political protests. In February 1972 the British Embassy in Dublin was burnt down following a demonstration protesting at the Bloody Sunday killings. In July 1981 extensive rioting followed another march on the Embassy, this time in protest at the British Governments stance on the IRA Hunger Strikes. There was criticism of the decision to allow the march to take place in the first place, but the Government defended the right to peaceful protest. Furthermore, it indicated that in spite of the violence it saw no reason to ban a similar march planned for the following week (Brewer et al 1996:100). The Minister for Justice, Mr Mitchell, stated that the governments predisposition will be not to interfere with the right to peaceful protest and he said that marches should only be banned as a very last resort. Extra police were on duty the following Saturday but the march passed off peacefully (Irish Times 20.7.1981, 27.7.1981). The most recent dispute arose in August 1986 in the wake of parading disputes in Portadown and over the Anglo-Irish Agreement. Peter Robinson of the Democratic Unionist Party led an estimated one hundred and fifty loyalists on a night-time sortie to the County Monaghan village of Clontibret. Having occupied the village the men painted slogans on the local Garda barracks, damaged cars and attacked two Gardai before being dispersed by plain-clothes officers who fired over the heads of the crowd. Robinson was arrested and charged under the Offences Against the State Act. He later pleaded guilty to unlawful assembly (Irish News 8.8.1986, 9.8.1986, 17.1.1987). Two conclusions can be made from these few brief details. First that there has been little controversy or conflict over the right to hold parades as such, and after the most recent and most serious of the disturbances the government was keen to reiterate and confirm the importance of the right to demonstrate. Second, each of the examples of disputes have been related to the conflict in the North rather than being related to issues internal to the state (although the dispute with the IRA in the 1930s blurs this distinction somewhat). Constitutional Rights The right to freedom of assembly was incorporated in the initial Constitution of the Irish state (Article 9) and today is guaranteed by Article 40.6.1.ii and 2 of the revised Irish Constitution of 1937 (Kelly 1980). This states that

While this indicates that freedom of assembly is recognised as an important civil right, the Constitution also clearly indicates that such a right is not unlimited. It can be qualified and subject to restrictions over concerns for both public order and morality. However, because the issue of parades and demonstrations has not been a contentious matter since the l930s, there is little in the way of legal authority on the meaning or interpretation of the Constitutional right to assembly: Apart from trade union cases, all the principal reported Irish authorities on public meetings and demonstrations pre-date the Constitution (Forde 1987:484). Most of these authorities in fact date from before partition and are based on British legal jurisdiction (Kelly 1980). Legal Constraints The Constitution explicitly permits some legal restraints to be placed on the right to assembly and specifically when there is a threat to public order. A number of subsequent Acts have empowered the Garda Siochana to ban assemblies in certain circumstances.

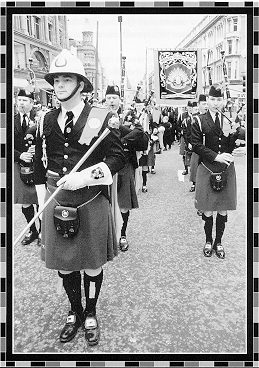

Although legislation allows for some degree of constraint on the freedom of assembly the law has rarely been called into use at parades or demonstrations. Senior members of the Garda Siochana who deal with public assemblies in Dublin stated that while it was possible to invoke the Road Traffic and Public Order Acts to constrain parades, to their knowledge they had not been invoked. Similarly, although they were able to prohibit demonstrations in the vicinity of the Dail, nobody had been prevented from holding such a demonstration since 1966 when a man was arrested and prosecuted for participating in an illegal protest by farmers. It was subsequently decided that it would be better to permit peaceful demonstrations rather than risk the area becoming a regular site of contentious illegal protests. Large numbers of demonstrations and protests are held in the vicinity of the Dail each year without causing any trouble. However there is some concern that the Criminal Justice (Public Order) Act, 1994, might be used to control some forms of political demonstration. In May 1997 a Socialist Worker Parry candidate was arrested tinder the breach of the peace provisions while campaigning for the Dail elections. A spokesperson for the Irish Council of Civil Liberties subsequently claimed that the new law had been widely used on individuals engaged in political and protest activity (Irish Times 12-6-1997). Practice While there is a Constitutional right to freedom of assembly, it must also be balanced with the rights of others to use public space. There is no requirement that organisers notify the police or any other agents of the state of their intentions, but the Garda Siochana are responsible for maintaining public order and freedom of movement more generally. In the early years of the troubles there was little contact between the Gardai and the republican movement over parades and demonstrations, by the 1 980s communication had been improved but there remains something of a rivalry over control of traffic at parades. Sinn Féin like their own stewards to take responsibility, while the Gardai are equally keen to retain control of the streets. The Garda Siochana encourage proper stewarding by the organisers, but they are also concerned that their own role in maintaining order should nor be usurped. Most groups do notify the Gardai of their intentions to hold a demonstration and, even if they are not informed the Gardai usually find out in advance: all parades and protests need publicity of some kind. A republican demonstration in Lerterkenny, in response to events at Drumcree in July 1996, did rake the local Gardai by surprise, but fewer people than expected turned tip and they were able to deal with it adequately. In most cases the Gardai take the initiative and contact the organisers of events to discuss the proposals for the route, and the trime, the scale and the nature of the event. Although they have no powers to prohibit parades, or to impose formal conditions, they can influence the route that is taken and the timing of the event. In most cases their main concern is with maintaining the flow of traffic, although on occasion they have had to deal with competing demands for demonstrations over the same route at the same time. Usually an acceptable compromise is reached but Gardai stated that they were aware that if a group insists on their right to demonstrate where and when they want then they have little power to stop them. Parades in Donegal County Donegal draws more strongly than other areas on the Northern custom of parading; the county hosts a diverse range of parades and demonstrations each year. St Patricks Day is widely marked in towns and villages, although usually by small events, well attended Easter Commemoration is held at Dunglow and smaller commemorations recur elsewhere. There are also a number of parades organised by the loyal orders. Many of these are feeder parades and are held prior to main anniversaries in the North; others are local church parades. The largest annual event in Donegal is the Orange Order parade in Rossnowlagh in early July. The Gardai usually talk to representatives of the local lodge some months in advance of the parade. They want to know the numbers of lodges and bands that are expected so that they can plan the policing requirements, although on the day this amounts to little more than organising traffic control. The Guards have no power to impose formal conditions on the parade, but informal agreements have been established over acceptable practices with regard to flags and bands. At the 1997 parade about 4,000 people took part in the parade, while there were no Union flags, there were six Ulster flags and a similar number of Orange Standards carried. There have never been any public order problems at the Rossnowlagh parade but echoes of the Northern Irish parade disputes have been felt elsewhere in the county in recent years. In July and August 1996 small protests were mounted at returning parades in Convoy and Manorcunningham, while a march and rally protesting about events at Drumcree was held in Letterkenny (Derry People and Donegal News 12.7, 19.7.1996). In Convoy the local Orange lodge re-routed their parade to avoid confrontation while in August the Manorcunningham branch of the Apprentice Boys ignored the protests and walked their normal route. In Match 1997 sectarian graffiti was painted in Dunkinnealy prior to a Boys Brigade parade and a similar incident occurred in Ballintra prior to the Rossnowlagh parade in July. In the first case the parade was cancelled, while in Ballintra the graffiti was painted over and the morning church parade went ahead as planned. In neither of the cases was a physical protest mounted. However, a small crowd of demonstrators did try to stop an Orange parade in St Johnston on the Twelfth, but Gardai ensured that the parade was able to take place (Derry People and Donegal News 18.7.1997). To date these protests have been small in scale, largely peaceful and easily controlled by the Garda Siochana. There is nothing to suggest that they will escalate in scale. Conclusions The history of parading in Ireland can be dated back at least as far as the fifteenth century and at times of political transformation parades and demonstrations have been the focus of contention and conflict. The extent to which this has not been a factor in recent decades can be discerned in part from the absence of any constitutional reviews to the basic rights to assembly and in part from lack of clear legal powers with which the Garda Siochana can control public gatherings. The most recent murmurings of disputes are but a small reflection of the contention the subject has generated in the North. To date they have not shown any signs of escalating, an indication of the declining social significance of the loyal orders in the Republic, where their parades really are little more than apolitical and non-contentious customs. At present the Garda are able to deal with the minor disputes over the time, place and manner in which parades are held through an informal process of dialogue and compromise. While there is recognition of the significance of the Constitutional guarantee of freedom of peaceful assembly, there is also a practical acknowledgement that such rights are not absolute and must also bear in mind the rights of others. Furthermore while at present the state is able to accommodate the level of demand for the right to public assembly, it has nevertheless introduced legislation that could be used to restrict the practical expression of those rights. To date it has nor needed to use those legal powers.

Democratic Dialogue {external_link} |