CAIN Web Service

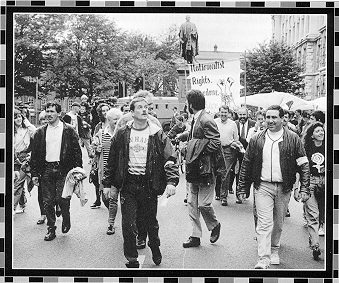

Politics in PublicFreedom of Assembly and the Right to Protest

The Right to Demonstrate Case Studies of Law and Practice F reedom of assembly and the right to demonstrate and to protest are widely accepted as basic civil rights and as such are embodied within all international charters of human rights. However, notwithstanding the universality of the principle, the various charters always allow for local interpretation of such ideals and therefore each legal jurisdiction has power to place limits on this and other rights.The case studies that we present in the following sections are drawn from a diverse range of countries. Each of these countries acknowledges, either through adopting international human rights charters, by constitutional guarantees, by legal articles, by common law or by a combination of these, the importance of freedom of assembly and the right to demonstrate. But many of these countries have also encountered a variety of problems over the practical expression of these basic rights and each country has developed its own means of balancing generalised ideals with local context. The value of presenting such case studies lies in the way that they can illustrate the wider context within which the laws and constitutional rights are interpreted in practice. What becomes clear from these examples is that there is no single model that can be held up as the perfect balance of ideal and practice. Each country will always have to balance an idealised concept of rights with local context. Nevertheless there is a limited range of issues that continue to be addressed when dealing with this subject. Sometimes these can be dealt with by law or through the courts, sometimes they have to be dealt with in a more fluid and pragmatic way, by developing good practice over time. Good practice cannot be imposed. It evolves over a period of rime at the interface of power relations between civil society and the state, between groups who wish to demonstrate, groups who wish to protest and those who have responsibility for the control of public order. This evolution will not necessarily be entirely harmonious or peaceful. The interests of the stare and the interests of the various sections of civil society will not always coincide, anymore than civil society could be seen as a unified or homogenous body with only one set of interests. The case studies show that parades, demonstrations, protests and marches are a fundamental part of the democratic process. They are also almost inevitability a source of conflict. To protest or demonstrate in favour of something means to protest or demonstrate against something else. Most protesting will offend somebody. In fact one could go so far as to say that if something is worth protesting about it ought to offend somebody. If the parties involved are not willing to compromise and recognise the complexity involved in balancing the multiplicity of rights and responsibilities it is difficult, if not impossible, to impose a lasting solution on social conflict. Some form of order might be imposed through regulation, but may merely become a target in itself. If this new order is successfully destroyed, then one has proved that it was not a fair compromise. Conflicts and disputes can be used to restrict the rights both of individuals and of communities, but they can also be used to consolidate, to extend and to clarify civil rights. While rights might be, or might seem to be, restricted during disputes, the process of resolving conflict should be part of the process of debating the nature of human rights and civil rights, their role in a democratic society, how they are balanced with social responsibilities and how they are to be safeguarded. These case studies show that the disputes over the right to) parade in Northern Ireland are not unique, similar problems have arisen in many of the countries that we have studied. We also hope that these examples illustrate that there is a wide range of ways through which such problems can be addressed and some of them may be appropriate in Northern Ireland. To repeat a point made earlier, there is no single or correct way to deal with the problem of balancing rights and responsibilities. But finding a solution does require a willingness from all parties involved to compromise and to negotiate, and a genuine desire to seek a resolution.

Democratic Dialogue {external_link} |