CAIN Web Service

Future Policies for the Past

Commemoration and rememberingBrandon HamberRecently, while reading the diary of Deneys Reitz - best known in South Africa for writing about his experiences as an Afrikaner in the Anglo-Boer war of 1899-1902 and then in the first world war - I came across some of his thoughts about the Irish. Reitz (2000: 365) wrote of how, following his participation in the war (ironically then on the side of the British), he had gone to Ireland, arriving shortly after the Easter rising: During one stage of the war, I had served with the 7th Irish Rifles in France and it struck me then as it struck me now, that the Irish politically resemble our Dutch-speaking element in South Africa. We too are more concerned with the sentimentalisms of the past than with the practical questions of today and tomorrow. Regardless of its provocative nature, this assertion made me realise how far back comparisons between South Africa and Ireland have been made. It also made me consider whether such comparisons arise from 'sentimentalisms', rather than systematic social or political analysis. Obvious as it sounds, South Africa and Northern Ireland are very different places. Their similarity lies not so much in the structure of their conflicts, but in their psychological outcomes. This is typified by the responses of individuals, ranging from those who minimise the conflict and deny any complicity to those who have experienced extreme trauma and repression. Reitz also conveys another myth - that some Irish, particularly now in Northern Ireland, are especially stuck in the past. All societies coming out of conflict draw on history to arm them-selves for the confrontations of the present, which for the most part are real, historically and materially based. The extent to which the past is used, and its cultural and social manifestations, may vary, but in all conflicts the ghosts of the past enshroud the divisions of today. The way the past is used in Northern Ireland has its peculiarities, but it is not exceptional. Reitz also implies that it is preferable to deal with 'the practical questions' of here and now, rather than spend time looking back - especially when the past is filled with emotion. Even Nelson Mandela has argued at times that the past needs to be forgotten in the interests of peace. In 1996, at the inauguration of the Enoch Makanyi Sontonga Memorial in Johannesburg, he said (Hayes, 1998: 48): 'Let's forget the past, and concentrate on the present.' Countries coming through conflict tend, in the name of pragmatism, to gloss over the fissures caused by decades of antagonism. Although this may be necessary in the short term, dealing with the past and the needs of victims of political violence is a continuing requirement, albeit difficult and fraught. And dealing genuinely with the past, and the experiences of those victimised by it, is as much about looking back as it is about pragmatism in the present. South Africa attempted to deal with the victims of apartheid violence largely through one approach, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. South Africa did not invent the truth commission - since 1974 there have been 15 around the world - but the TRC was to capture the world's attention. This was partly due to the international interest in the fight against apartheid. The South African model also promised an alternative way of peacefully resolving entrenched differences. So the notion of using a truth commission to deal with political conflict gained momentum: Indonesia, Sierra Leone and Northern Ireland are flirting with the idea. But how well did South Africa fare? Archbishop Desmond Tutu said that without the compromises made during the negotiations to ensure majority rule the country would have gone up in flames. From this perspective, the agreement by the African National Congress to grant amnesty to perpetrators of apartheid violence was a pragmatic choice. Amnesty was the cost - a high one for victims - of saving innumerable lives lost had the conflict continued. Unlike in Chile, amnesty in South Africa was neither blanket nor automatic: conditions applied and the TRC was the vehicle. Perpetrators of political violence, from every side, had to disclose full details of past crimes. Simply put, it was agreed that justice would be overlooked, provided the perpetrators told the truth. Truth was considered vital to understanding what had happened, assisting victims to come to terms with the past and preventing its repetition. Victims of political violence were also given the opportunity to tell their stories. The TRC then made recommendations regarding possible reparations, as well as proposals to prevent future human-rights violations. The TRC process began in December 1995 and ended, technically at least, when the commission handed its 3,500-page report to then President Mandela in October 1998. The amnesty process still continues. About 20,000 people came forward and told how they had been victimised under apartheid. More than 7,000 people applied for amnesty and, to date, nearly 800 have received amnesty for such crimes as murder and torture. Public acknowledgment of past crimes was the TRC's greatest success. The brutal horrors of apartheid found their way, via the media, into the living-room of every South African. An undeniable historical record was created, and it will be very difficult for anyone to deny the impact of apartheid violence. For a minority of victims, suppressed truths about the past were also uncovered. In some cases, missing bodies were located, exhumed and respectfully buried. For others, the confessions of perpetrators brought answers to previously unsolved political crimes - crimes which the courts, due to expense and inefficiency, might never have tried. Yet for many the TRC began a process it was unable to complete. Many victims felt let down, and no closer to the truth than before they told of their suffering. Irrespective of the feasibility of investigating every case, victims' high expectations were dashed, and in their eyes this undermined the commission's credibility. Justice has remained a burning issue. Politicians may have been able to justify the exchange of formal justice for peace, but it has been difficult for victims to watch while the perpetrators have received amnesty. Moreover, the government of Thabo Mbeki has been slow in responding to the TRC. More than two years since the proposals for reparations were tabled, they still have not been discussed in Parliament; nor, indeed, have the TRC's broader recommendations. There have also been debates about the wider merits of the commission. At the very least, the reconciliation project - the TRC at its helm - brought South Africa through the transition with relative political stability. The humanist approach of Messrs Mandela and Tutu brought compassion to an extremely brutalised country. Despite the horrors revealed by the TRC, glimmers of humanity shone through and provided some hope for the future.

'I don't think actually that what we're going to arrive at is a truth commission. I think we're going much more to see a series of truth processes that are going to be painful for everybody, because I don't think there is any right or wrong. I don't think that anybody is going to come out of that process with their head held high and nobody is going to come out and say: we were clean. Nobody was clean over the last 30 years.' For some, however, reconciliation has become a mere euphemism for the compromises made during the political negotiations - compromises that sustained white control of the economy at the expense of structural change. From this perspective, the commission also missed the bigger picture by defining victims only as those who experienced intentional physical violence. Those who were not victimised directly in this way but suffered more broadly from the economic ravages of apartheid were excluded. Another, more cynical, view is that the rapprochement between the old and new régimes was a strategy to consolidate a new black élite under the banner of reconciliation. These different perspectives demonstrate the complexity of issues of oppression and violence, and how past events shape the process of reconciliation. In South Africa, the balance of power dictated the terms of the amnesty: the ANC had too little power to prosecute the perpetrators of apartheid violence, but enough to impose amnesty conditions. Lauding South Africa for its innovative approach - trading truth for amnesty - is meaningless without referring to its context. South Africa's approach to reconciliation cannot be applied elsewhere without first analysing the power relations in that society. While there may be sufficient political space in Northern Ireland for the reopening of the inquiry into the Bloody Sunday massacre of 1972, it is unlikely that its politicians and the British government would agree to a broad truth commission embracing all the events of recent decades. In the context of its 'imperfect' peace, most parties fear that uncovering the truth could weaken their position and increase tension, rather than advancing peace at this stage (Hamber, 1998). A truth commission should be used to consolidate peace after a formal agreement has been secured, not mistakenly used to try to make peace. This does not mean questions of truth and justice will disappear in Northern Ireland, or elsewhere. While power relations shape the path a country follows in the post-conflict phase, dealing with the past cannot be put off forever. In Namibia, 10 years after independence, there are now vocal calls from victims for an investigation into the atrocities committed by the South West Africa People's Organisation in its camps. In Mozambique, people felt that a truth commission would be too risky, given the extent of violence committed by all sides during the civil war. But the past continues to play itself out, as people struggle to rebuild their lives in communities reeling from years of violence, injustice and suspicion. A truth commission is just one vehicle of reconciliation: commissions of inquiry, tribunals and grassroots initiatives can also help victims and perpetrators come to terms with the past. Strategies for dealing with the past can also include the documentation of victims' stories - in the form of books, archives, poetry, writing, theatre and song - as well as more structured truth-telling processes, ranging from counselling to commemoration through monuments and rituals. Governments, voluntary groups, communities or individuals can adopt such approaches individually or, ideally, in partnership. Their importance, however, is in drawing public awareness to the plight of the victims of the past. They should be used to mend relationships, not to alienate those from different communities. Many stories of the hardships and violence of the past in Northern Ireland are inevitably untold; these stories will need to (and will) filter into the public space. The challenge is for policy-makers, government and communities to find frameworks to deal with this eventually. A truth commission is only one, limited, institutional framework. More importantly, a continuous process of dealing with the needs of victims should be put in place. A public debate on how best to deal with the past, and the needs of victims, is a necessary first step. Only one aspect in this debate is universal: victims have a right to truth, justice and compensation in the wake of political violence. These 'universals' can, however, be more difficult to implement than at first glance. In the so-called interests of peace-making and political stability, leaders - and, often, the majority of people in a country - may limit these rights. This pragmatic choice may have benefits in the short term but will demand close attention as the peace unfolds. Truth is a contested terrain in the post-conflict phase. Perhaps we would all agree that victims have the right to know what happened to their loved ones who were killed or 'disappeared'. But, in one way or another, we all resist the truth about the past coming to the surface: each one of us is fearful. A South African colleague, Grahame Hayes, eloquently captures this resistance (Hayes, 1998: 46): the perpetrators fear the truth because of the guilt of their actions; the benefactors fear the truth because of the 'silence' of their complicity; some victims fear the truth because of the apprehension of forgetting through the process of forgiveness; and other victims fear the truth because it is too painful to bear. He concludes that reconciliation takes place at the point where we struggle with understanding our own personal resistance to uncovering the past. This is a challenge to society at large, not just to those with political power. At the same time, we should not fall into the simplistic trap of arguing that revealing (telling the truth) is instantly healing. Dealing with the truth, once it is out, is a complex and difficult process, which will plague Northern Ireland for decades. Nor does extensive trauma counselling equate with dealing with the past. Of course, victim support services are necessary, but an over-emphasis on counselling and support can deflect attention from the other needs of survivors. Many victims are unlikely to divorce the questions of truth, justice, the labelling of responsibility for violations, compensation and official acknowledgement from the healing process. Therein lies the challenge: we can envisage setting up sufficient support services for all victims of political violence, but integrating their other needs - perhaps overridden in the name of peace, such as the right to justice - is infinitely more complex. Models and policy initiatives need to look to the individuality of victims and their particular context, and to the long term. Governments supervising transition may find themselves at odds with victims, even communities, as the desire to move on politically is normally more rapid than for individuals. Individual recovery, over time, is linked to the reconstruction of social and economic networks, and of cultural identity (Summerfield, 1995: 25). South Africa attempted to meet these multiple needs through the TRC. But even the commission was a flawed process: did it uncover enough of the truth and did it offer victims sufficient support, to offset the denial of their rights in the name of peace? Inadequate reparations and the compromise of amnesty exacerbated the problem. It has been argued that South Africa achieved a necessary balance between ensuring peace and guaranteeing some truth and victim support. Yet without broad, structural change, and continuing recognition that victims' rights to justice and reparation have been violated through the peace process, it is unlikely the TRC will ever be judged to have been sufficient. This provides some perspective on the debate as to how Northern Ireland can best remember, and commemorate, the past, and deal with victims and survivors. The rights to justice, truth and reparation are real for victims of political violence, and these principles need to be agreed. And it needs to be understood that, for the survivor of political violence, truth, justice and reparation are linked. Truth complements justice, justice can reveal the truth, and reparation is not only a right but is integral to the rule of law and to the survivor's trust in a just future. Reparation (and often punishment) is the symbolic marker that tells the survivor justice has been done; simply put, justice is reparation (Hamber, Nageng and O'Malley, 2000). These rights, and the complex needs of survivors with regard to truth, justice and reparation, may not be attainable due to compromises made to ensure peace. But, if so, policy-makers and government will be required to deal as best they can with the legitimate frustrations of victims whose rights have been violated a less than ideal position. Finally, I would return to Deneys Reitz. The maintenance of peace and social reconstruction in Northern Ireland will undoubtedly become the 'practical work of today and tomorrow' over the next few years. But if we want to foster genuine reconciliation in the region (and in South Africa, for that matter), we must have the courage to walk headlong into, and deal with, the 'sentimentalisms of the past' a process that may take as long as the past itself. Bibliography Hamber, B (ed) (1998), Past Imperfect: Dealing with the Past in Northern Ireland and Societies in Transition, Derry: University of Ulster and INCORE Hamber, B, Nageng, D and O'Malley, G (2000), 'Telling it like it is survivors' perceptions of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission', Psychology in Society 26, 18-42 Hayes, G (1998), 'We suffer our memories: thinking about the past, healing and reconciliation', American Imago 55, 1, spring Reitz, D (2000), The Deneys Reitz Trilogy: Adrift on the Open Veld: The Anglo-Boer War and its Aftermath 1899-1943, Western Cape: Stormberg Publishers Summerfield, D (1995), 'Addressing human responses to war and atrocity: major challenges in research practices and the limitations of western psychiatric models', in R J Kelber, C R Figley and B P R Gersons (eds), Beyond Trauma: Cultural and Societal Dynamics, New York: Plenum Press

ResponseAvila KilmurrayThe past need not always haunt us, but can offer pragmatic solutions in the present if we are prepared to deal with it in a genuine manner. This is a particularly important point in Ireland, where we are often accused of dwelling on the past. But it is difficult to talk about dealing genuinely with the past when we are still in the midst of a political struggle over the present and the future. Perceptions of history are an important part of that struggle, which has sharpened around the issue of victims - indeed around the very definition of the word. Brandon commented on the importance of leadership rooted in compassion, rather than partisan passion. One of the most dismal legacies of the years since the Belfast agreement has been the spectacle of party-political struggle over the 'ownership' of victims. While the concern of some politicians is undoubtedly compassionate, for others any compassion has been selective. Perhaps we need a firmer sense of political stability to secure that leadership, although in South Africa the latter was instrumental in establishing stability itself. Nor is the necessary confidence to confront issues of truth and justice yet apparent in Northern Ireland (or, for that matter, in Britain, where the government still finds it incredibly hard to come to terms with having been an active protagonist in the violence of the last 30 years). It is difficult when so many participants in the struggle still take refuge in moral certainties, a refuge they then deny to others.

'The most painful battle over the last few years has been over who is a victim and who is not ... We're still caught up in that: some deserved what they got and some didn't. It's a very difficult discussion but a very important discussion in relation to commemoration and remembrance.' Brandon referred to the variety of potential approaches to recording the experiences of victims and perpetrators (and those who were both). Diverse approaches have been piloted in Northern Ireland; many have much to recommend them. Certainly, variety is necessary to reflect the different needs of victims themselves. If we engage in recording stories, however, we need to be able to deal with the messages - often conflicting messages - emerging from them. The diversity of the interests, views, experiences and responses of victims is worth underscoring. If we are to take commemoration and remembrance seriously, we have to move beyond the who-is-a-real-victim? issue; otherwise, we are in danger of creating more hurt and controversy. Brandon spoke of the need for clarity about the context. Unfortunately, that is the very thing that we do not have in Northern Ireland. Essentially, we still have two philosophical explanations of the recent - and not so recent - past. There are those who see a sharply divided society, formed on the basis of a sectarian head-count, with endemic discrimination, leading to violence. As against this, there are those who see Northern Ireland as a normal democratic society which experienced an aggravated crime wave over the past 30 years. This philosophical fault-line has destabilised the interpretation, and so implementation, of the agreement. It has also haunted discussion of the remembrance and commemoration of victims of violence. Remembrance can take place on a number of levels: private, public and social. We all remember the facts as we know them or wish to know them. Similarly, a local context will influence how we remember things. As the research by Smyth and Fay (2000) underlines, how people remember the violence and the victims as a Protestant in south Armagh or west Fermanagh will be quite different from how a Catholic will remember in inner north Belfast. So much of our remembrance is like a kaleidoscope, but while we still have a divided society it will be difficult to appreciate its full extent. This is why it is very important to create space and opportunity to exchange perceptions, to check out memories against those of others. One of the issues that dogs remembrance is lack of disclosure. This, in turn, gives rise to conspiracy theories about what did, or did not, happen in cases of violent death or injury. Any effective disclosure would require amnesty arrangements - and that is a difficult issue for many people. There is also the question of disclosure by the state. This is often seen as a concession to republicans and as unwarranted, given little corresponding movement from that quarter. But should the state and paramilitary movements be judged by the same criteria? Many would argue that more should be expected of the former. Public or social commemoration must be inclusive if it is to contribute towards overall healing. If not, it would do more harm than good. Northern Ireland is not yet at a stage where we could envisage a parallel to the Vietnam memorial wall in Washington, with its naming of the dead side by side. But there remain the options of developing a place - a forest, a park or the like - as a sanctuary of remembrance. We are still at the stage of quiet, private remembrance - better that than commemoration that is combative in nature. We need to create a range of spaces and develop a variety of approaches. We also should be wary of remembrance being overtaken by detached academic analysis, as this might further disempower victims and survivors. Equally, we have to develop the shared context and confidence that will allow remembrance to be open to a more general discussion and, where necessary, challenge. We need to work to create an inclusive kaleidoscope. What we cannot allow is that we be told to 'draw a line in the sand' - forget about the past and move on. As Brandon suggested, it is crucial that we learn to deal with the past in a positive manner. In any case, lines in the sand are invariably washed away. Bibliography Smyth, M and Fay, Marie-Therese (eds) (2000), Personal Accounts from Northern Ireland's Troubles: Public Conflict, Private Loss, London: Pluto Press

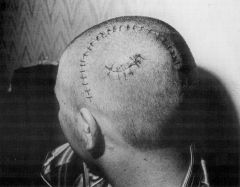

Killings by the stateBill RolstonI want to focus on one category of victims - those killed by state forces during the Northern Ireland conflict. Much of this chapter is based on interviews with 20 families who have campaigned for truth and justice in relation to the death of their loved ones at the hands of the state (Rolston, 2000). State forces have been responsible for 10 per cent of all deaths during the conflict. The major perpetrator in state killings has been the army, responsible for over 82 per cent. Next has come the Royal Ulster Constabulary, at approximately 15 per cent. State killings figured largely in the early days of the conflict. There were 62 deaths attributable to state forces before the most-publicised instance, Bloody Sunday, in January 1972. The worst year for state killings was 1972, when 83 people died as a result. In the three years 1971-73, there were 160 state killings, 45 per cent of the total of such deaths. Civilian deaths constitute the largest category of victims of state killings - over 50 per cent. Almost all such victims were unarmed; the vast majority - 86 per cent - were Catholic. The next largest category is republican paramilitaries, accounting for 37 per cent of state killings. Remarkably few loyalist para-militaries were victims of state killings - only 4 per cent of the total. All but two of the latter killings occurred before 1975. Many human-rights activists have referred to those killed by state forces as 'forgotten victims'. They would argue that there have in effect been two classes of victims: 'deserving' and 'undeserving'. The latter were presumed less than innocent or, worse, downright culpable - implicated in their own fate. Thus, at the top of the hierarchy of victims, were those deemed 'innocent' - usually women and children, usually killed by paramilitaries. At the bottom were members of those same paramilitary groups killed by state forces; they often attracted little widespread sympathy outside the communities from which they drew support. Raising the issue of state killings while the violence raged was difficult. First, there was an unquestioned belief that the state does not act as a terrorist, and does not kill without reason or justification. Secondly, there was a presumption of 'no smoke without fire', despite protestations of innocence. Thirdly, these deep prejudices and presumptions were disseminated by powerful institutions, especially the media. And there was deliberate misinformation and manipulation of the media by state forces, ensuring that a partial or downright false story was the first in the public domain, and therefore the most likely to be believed and remembered. Such was the power of this ideology that it was possible in the cases of state violence to override the most basic right to presumed innocence. Thus, it was usually presumed (indeed, often stated) in official accounts that children killed by plastic bullets were involved, or at least caught up, in riots - the implication being that there was contributory negligence. To draw attention to victims of state killings was to risk being labelled 'soft on terrorism'. Criticism of the state's human-rights record was usually condemned as 'playing into the hands of the terrorists'. It was even worse for relatives who dared to demand disclosure or prosecutions: to agitate for such was to draw down the wrath of state forces. Vilification of the dead was echoed in the treatment of those who sought truth and justice. In most cases, those interviewed said they had never been officially informed by the RUC or anyone else that the killing had taken place. Others were informed by the police or the army in the most callous of ways. As Peter McBride's body lay in his house awaiting burial, soldiers drove past shouting 'One down. One nil'. When Kevin McGovern's mother phoned the RUC to inquire about her son, she was told: 'You'll get his body in Magherafelt morgue.' For many, the first intimation of the death was an RUC raid on their home. In such cases, relatives were convinced that the police were on a 'fishing exercise', searching for some information that might allow them to tarnish the name of the victim and thereby excuse their own involvement. Misinformation about the character of the dead person was highlighted by all interviewees. In each case of state killing there have been two opposed versions: that of the state and that of relatives and human-rights campaigners. There is one way out of the dilemma of deciding which is correct. The state has the resources to be much more than an uninformed observer: it has the means to investigate these killings as systematically as those of every other person killed in the conflict. Has it done so? The emphatic answer is 'no'. For example, campaigners in the case of the death of Louis Leonard pointed out that the RUC had made no attempt to seal off the scene of the crime: 'There was no investigation. Louis' case was a murder in a small village and it was never treated like you would imagine a murder to be treated.' The experience was similar for the family of Carol Ann Kelly: 'There was never a proper investigation into Carol Ann's death. They didn't do any measurements or take statements from witnesses. A lot of the local people went to Woodburn Barracks to give statements and they were told it wasn't necessary.'

'I think as citizens we need the truth. For those of us who have supported the state and the security forces in the past, we particularly need to know who it is we are being loyal to, what they've been up to and whether or not we can mitigate that loyalty with a dose of what they've been up to.' Even the most obvious of police routines - the interviewing of those involved in killing - was often ignored. For example, the SAS undercover soldiers who killed three IRA members in Gibraltar were whisked back to England immediately and only interviewed two weeks later. Loretta Lynch, a campaigner in the case of Mr Leonard, summed up the conclusion of many relatives: 'Not only was there no investigation, but there was a concerted effort not to investigate.' Nor are such comments confined to relatives. After examining the RUC's investigation of the killing of six men in north Armagh in 1982, the then deputy chief constable of Greater Manchester, John Stalker, concluded: 'The files were little more than a collection of statements, apparently prepared for a coroner's inquiry. They bore no resemblance to my idea of a murder prosecution file.' Yet families found themselves targets for undue attention by the RUC and the army. The harassment was usually verbal and highly offensive. The family of Charles Breslin were subjected to numerous taunts, such as 'Charlie's a Tetley tea bag' a reference to the fact that he had been shot at least 13 times. The brother of Seamus Duffy, killed by a plastic bullet fired by the RUC, was frequently harassed: 'Do you want to be the next?' he was asked. The younger brother of Pearse Jordan, shot dead by the RUC, received similar treatment. This harassment was not confined to relatives of republican activists. Moreover, it increased the more the relatives became involved in political action to achieve justice. Robert Hamill was killed by a Protestant mob in Portadown; his family claim police nearby did nothing to intervene. According to his sister Diane, commenting on the attention she and her family had received from the police, 'If we had not stood up and said this was wrong, they would probably not have given us so much hassle.' Despite the odds against them, many relatives hoped to gain some satisfaction by having their day in court - a trial or inquest. But there have been very few prosecutions in relation to state killings. And very few of these have led to custodial sentences. Even then, the guilty were often released within a few years. Moreover, the experience of the inquest was usually a frustrating one. As a result of changes in the coroners' rules for Northern Ireland introduced in 1981, inquests can only record findings as to the identity of the dead person and how, when and where he or she died. In addition, public interest immunity certificates were frequently issued, preventing disclosure of information on grounds of 'national security'. Police and soldiers implicated in the death did not have to appear, but could send unsworn statements. Many of those interviewed were adamant that they did not want to see anyone imprisoned for killing their relative; given how much they had suffered, this showed remarkable tolerance and magnanimity. Others insisted that they wanted to see prosecutions, but a court case was seen as a means to an end - the truth. At one level 'truth' refers specifically to the facts: there is no closure without disclosure. But, fundamentally, even if the facts, including the names of the perpetrators, are already well-known - and in many cases they are - relatives demand official acknowledgment of wrongdoing. Kathleen Duffy, whose son Seamus was killed by a plastic bullet, put it this way: 'I just cannot understand how we don't get recognition. It's the same hurt, the same as any other murder ... I want the same recognition as everyone else. I don't want to be any different. I want to be on the same footing as any other mother whose son has been murdered. I think I have the right to that.' How can the relatives achieve this acknowledgment? One mechanism which has been tried in at least 19 societies in the past two decades - including, most recently, South Africa and Guatemalais - a truth commission. A truth commission marks a symbolic break with the horror of the previous régime. It states unequivocally that what the state did - torture, 'disappearances' and killings with impunity - was wrong and should never recur. In conjunction with other legal and political changes, it may mark a turning point. Although a truth commission may appear simply symbolic, it is intended to underwrite a new consensus about human rights - without which there is no assurance that the future will be any different. Some have argued that we are already at that point in Northern Ireland, and that elements of a definitive break with the past are present in mechanisms established by the Belfast agreement. The Patten commission on the reform of the RUC held a number of well-attended and animated public meetings, leading some of the commissioners to conclude that it was the equivalent a truth commission. Some commentators have suggested the Saville inquiry into Bloody Sunday could become a mini-version. The Bloomfield report on victims proposed policies to allow relatives access to education and business start-up; similar policies emerged, for example, from the truth commission in Chile. The criminal- justice review recommended a broad range of reforms. Finally, out of the agreement came a human rights commission, alongside the UK-wide incorporation of the European Convention on Human Rights into domestic law. But what distinguishes the current situation from that in most societies embarking on a truth commission is an absence of consensus on the legitimacy and purpose of these innovations. There are three ways in which these events are represented. First, the changes are described as, at best, unnecessary and, worse, an attack on respectable institutions which have proven their worth in the defence of democracy - in effect, a victory for 'terrorism'. This is the position of many unionists. Secondly, the reforms are presented as a welcome and appropriate recognition of political change. The 'terrorist menace' is potentially gone forever, so there is an opportunity to professionalise and modernise institutions. Such changes do not, however, constitute any criticism of the past. This position is held by the British government. Thirdly, the changes are deemed cosmetic and likely to be superficial. They do not represent the root-and-branch transformation required to achieve a break with the past. This is the position of republicans and some other nationalists. So, we are not even at the stage at which other countries had arrived when they established their truth commissions. Nor does it follow that - if and when we did arrive at that point - a truth commission would magically solve all our political problems. The South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission proves that.  The argument of force attending an IRA funeral in Co Tyrone Although it gained wider support in the society than might have been imagined and led to remarkable instances of disclosure and reconciliation, the TRC was criticised by some of those it might have been expected most to help. Thus, the family of the murdered black-consciousness activist Steve Biko objected to the trade-off of amnesty in return for disclosure. Even those who reluctantly accepted the necessity of such a compromise ended up feeling a sense of anti-climax. All their eggs, as it were, had been placed in one basket. No one event, no matter how wide-ranging, could hope to give everyone a sense of accomplishment. For those who had suffered at the hands of the apartheid state there was the realisation that some of those responsible were never going to own up, that the truth would not be total, and that there would be often little more than a begrudging acknowledgment of injustice. And because the TRC was a one-off event, there was no second chance to bring about a closure. Despite this and other shortcomings, the TRC had one irrefutable benefit for victims: it acknowledged the suffering they had experienced, it vindicated their demands for equal recognition, and it laid down a powerful social marker of condemnation of the actions of the state in the past and of good intent for the future. Does this mean that there should be a truth commission in Northern Ireland? Some relatives say yes - aware that, as in South Africa, they may have to compromise. Truth may require less than full justice, especially in terms of prosecutions. Their compromise would be seen as the price that must be paid for building a future society where the protection of human rights is central. That a truth commission however seems unlikely - in the absence of a consensus in the society that there should be such a mechanism - might suggest a pessimistic message. On the contrary, given that truth and justice cannot be guaranteed by one event - even one as significant as a truth commission - it follows that truth has to be built through a patchwork of events and mechanisms. Inquiries, prosecutions, the disclosure of documentation, public events and archiving of memories can in the end contribute to an acknowledgement that there are no second-class victims and that the campaigns of relatives of state victims have been justified. As a society, we are not yet at the point of inclusiveness. With the agreement came the decision to release politically-motivated prisoners. To 'sweeten the pill' for many victims and relatives, there was a balancing commitment to addressing their plight. The Bloomfield report offered a welcome focus but the sting in the tail of this new-found concern was the 'forgotten victims' and their supporters. Relatives of those killed by the state have argued for equality of treatment, as held out by the agreement, and have won a place in the debate. But that debate is not yet over. For some, inclusion has been conceded begrudgingly; it is far short of heartfelt acknowledgment of wrong done. Elsewhere, truth commissions have played a role in bringing about that acknowledgment. Whatever the mechanisms, true justice demands we reach that point also. Bibliography Rolston, B (2000), Unfinished Business: State Killings and the Quest for Truth, Belfast: Beyond the Pale Publications

ResponseDave WallI believe that mechanisms must be found to enable a shared truth to be told. These must be based on reconciliation and reparation, not retribution. There are examples of processes from which we can learn, such as the South African TRC. But whatever process we adopt will have to be specifically designed to meet our particular needs. Bill's paper only comments on killings by the state. Certainly, the state has a particular responsibility to act within the law; failure to do so fundamentally undermines all our human rights. In that sense the state is deserving of special attention in the search for truth. But the great majority of killings in Northern Ireland have been carried out by paramilitary organisations. The combination of state and paramilitary killings has left a bitterly divided society. Identification of the wrongdoings of the state alone is unlikely to achieve reconciliation. The violence has been very intimate and localised. Victims often know, or believe they know, who killed their loved one. Often these people have lived in the same street, the same village, the same community. This intimacy requires an approach to truth, justice and reconciliation that reflects this special nature of our conflict. Bill accurately reflects that, in large part, victims are more concerned with knowing the truth than with retribution. But I do not entirely concur with the view that those calling for judicial inquiries see this only as a means of identifying truth. We live in a bitterly divided and punitive society. He reflects on the small number of prosecutions of British soldiers but the early release of Pte Clegg and others, and their return to the army, produced a very angry response. While this was expressed in the language of equal treatment, there was certainly a strong element of concern for retribution. Bill also reflects that other countries had a consensus enabling them to move on to a truth-and-reconciliation process. In one sense that is correct: the TRC did follow extended and extensive discussion across South Africa. Yet, while there was considerable consensus, in the end the co-operation of the agents of the apartheid state, the security services, was only secured in exchange for amnesty. Therefore a truth-finding process (or commission) comes as part of the achievement of consensus, of restoring relationships. All sides have to believe they have something to gain. He does correctly identify the disillusionment of many in South Africa after the conclusion of the TRC, but my understanding of its cause is that the South African government has failed to implement the recommendations in the TRC report about the compensation of victims. There is a view that there is an imbalance between an amnesty for perpetrators yet no compensation for victims. During the visits of Alex Boraine, vice-chair of the TRC, to Belfast over the past two years, we discussed with a wide variety of organisations and individuals the relevance of a truth-finding process in Northern Ireland. The vast majority of participants felt the achievement of a shared truth was an important objective. Denial was not considered an option by many. How and when such a shared truth could be realised was, of course, not easy to identify; nor was the appropriate phasing with other political developments. The discussions so far indicate key elements to address. First, whatever the process we adopt to achieve truth, it is an essential requirement in our quest for peace. Secondly, we need extended and inclusive discussion and debate. Thirdly, and most importantly, we need to establish the political and moral authority to support a truth-finding process. We do not yet know what kind of process, if any, will suit Northern Ireland in establishing a shared truth. It will not be the same as in South Africa but we will not achieve a political peace without mutual recognition of the nature of the past. Dr Boraine identified three ways forward. First, we could 'put the past behind us' and engage in collective amnesia. But victims do not forget; to ignore this re-victimises them. In South Africa this was not considered a viable option and it is not a sensible option for ourselves. Secondly, we could hold a series of trials or prosecutions. Alleged perpetrators would be charged and, if found guilty, penalised. This approach has serious limitations. Where would prosecutions begin and end? Would it be possible to reconcile different and conflicting communities if the resolution involved punishment? Arms are still widely available in Northern Ireland and those who hold them might seek revenge for any punishment handed out. Thirdly, we could develop a restorative-justice approach, enable people to tell the truth so everybody knows what has happened, and contribute towards a common history: who killed whom and why? This would acknowledge what had happened and why it had happened, establish accountability and responsibility for those actions, and enable some people to say sorry and to move on. While there must be much fuller discussion with all stakeholders, the possibility of a structured truth-finding process will be dependent on the ability of our politicians to achieve a consensus on the way forward. Following on from Dr Boraine's earlier visits, it is now intended by September 2001 to submit to London and Dublin, and the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister, a report identifying a programme of action that may lead to a successful truth-finding process. The South African TRC was born out of a political settlement. While not all sectors of South African society trusted the new government, it gave the commission the authority and independence to carry out its task without interference. The difference between the nature and role of the state in South Africa and in Northern Ireland cannot be overemphasised. South Africa had a new state. We will have the same state, albeit working in a rapidly changing political environment in the UK, Ireland and Europe. That state must also be part of any truth-finding process. It was difficult in South Africa to get perpetrators who acted on behalf of the state to give evidence (many did but many in positions of command did not). Will it be even more difficult, where the state authorities have not changed, for the state to give evidence? Does this again point us in the direction of a series of inquiries, rather than a truth commission? What does this indicate about those inquiries in terms of amnesty for witnesses, reparation for victims and the relationship with any prosecutions? I think inquiries will play a significant role in the development of a consensus about the need for a defined process. As more evidence emerges of the truth of our conflict, there will be greater need on all sides to see the story from all sides, to develop a shared truth. In the same way that the Belfast agreement was established and its implementation is continuing because there really is no other show in town, I believe we will develop a consensus as to the need for a defined and inclusive process of truth-sharing. Inevitably, this will involve trade-offs between perpetrators and victims. It must be sensitive to our intensely localised conflict. It may well involve a combination of elements: inquiries about identified events, a more general process for other incidents and some mechanism for very local support and mediation. Whatever the mix of mechanisms and strategies, it must be aimed at reconciliation and restoration. I do not believe that a process based on retribution can produce closure. In its 'Declaration of Support', the Belfast agreement reflects the values that will be at the heart of a truth-finding process: The tragedies of the past have left a deep and profoundly regrettable legacy of suffering. We must never forget those who have died or been injured, and their families. But we can best honour them through a fresh start, in which we firmly dedicate ourselves to the achievement of reconciliation, tolerance, and mutual respect, and to the protection and vindication of human rights for all. We are committed to partnership, equality and mutual respect as the basis of relationships within Northern Ireland, between North and South and between these islands. Our task must be to help the political parties to identify a process that can lead to a shared truth, based on these values.

'Ask the victims again what it is they want. Some of them say they want inquiries, some of them say they rule out the issue of prosecution and punishment altogether, but what most say is they want the truth ... facts and acknowledgment.' I conclude with the following questions taken from the report of one of Dr Boraine's visits (Boraine, 1999): 1. What special measures are required to deal with our intensely localised conflict? Bibliography Boraine, A et al (1999), All Truth is Bitter, Victim Support Unit Northern Ireland/NIACRO: Belfast

The 'discovery' and treatment of traumaMarie Smyth Trauma n (pl ata, -as) wound, injury; painful psychological experience etc, emotional shock, esp as origin of neurosis. Trauma (trow-mã) n (pl mas mata) 1. A wound or injury. 2. Emotional shock producing a lasting effect upon a person traumatise (trow-mã-tiz) v (traumatized, traumatizing) (Oxford American Dictionary, 1986) Trauma has more than one meaning and it is not always clear. The word is used to refer to both physical and psychological wounding. Perhaps this should suggest a more holistic approach - that both the physical and psychological be borne in mind. Moreover, in a culture increasingly influenced by the popularisation of psychology, and by highly specialised and demarcated services, material circumstances can be ignored, often at our peril. The psychologising of everyday life (Shorter, 1997) and the decreased tolerance of psychic pain associated with increased expectations of happiness (Giddens, 1993) provide a broader social context for any discussion of trauma. In his polemic on the history of psychiatry, Shorter (1997: 290) writes: Since ancient times, both boys and girls have become anxious about scary stories. Yet it would have occurred to no one across the centuries to give psychiatric diagnoses to these anxieties about phantasms, not at least until the advent of 'post traumatic stress disorder' (PTSD), a syndrome initially associated with the trauma of combat. Whether a distinctive veteran's psychiatric syndrome involving stress actually exists is unclear. But even if it exists, once PTSD became inserted in the official psychiatric lingo, the popular culture grabbed it and hopelessly trivialised it as a way of psychologising life experiences. By 1995, therapists were talking about 'PTSD' in children exposed to movies like Batman. According to one authority, 80 per cent of children who had watched media coverage of a crime hundreds of miles distant exhibited symptoms of 'post traumatic stress'. The anxieties of children themselves were nothing new under the sun. New was psychiatry's willingness to persuade parents that the quotidian problems of maturation represent a distinct medical disorder. In this cultural climate, which Shorter deftly describes, 'everyone is a victim'. And terms such as 'traumatised' are used to describe effects as disparate as responding to a film and witnessing the killing of a close family member. The increased cultural and social intolerance of psychic pain - allied with the growing use of psychotropic drugs for the management of unhappiness - and an increasingly individualised culture have created a context in which large, undifferentiated numbers of people can acceptably claim to have been traumatised. Yet this can only increase the demand on the diminishing supply of the milk of human kindness, and reduce the chances of those in dire need receiving their due share.

'It is extremely difficult to make a generalised statement about what victims want - including that victims want the truth - because, in my experience of working with people, some people find the truth too difficult to bear ... However, I do think that we need the truth and that's a different statement. Let's not hang the truth on the necks of the victims: they have enough problems of their own to get on with ...' Nor do the supposedly more scientific psychiatric frameworks such as PTSD assist, since they themselves are artefacts of the same social circumstances. Young (1995) contextualises current thinking about trauma and traumatic memory in the emergence of new concepts of human nature and consciousness and of psychiatry as a medical speciality. PTSD does not exist as an independent fact: we have invented it as a way of summarising and bringing together things that were understood differently - or perceived as unremarkable - in the past. Until the advent of the Bloomfield report (Bloomfield, 1998), scant systematic official attention had been paid to those bereaved or injured in Northern Ireland's 'troubles'. This was, in part, due to the exigencies of the times: physical survival, rather than psychological well-being, was often the priority. Yet, even when the violence was at its peak, there was a Criminal Injuries Compensation scheme (also reviewed by Bloomfield) and a property-related Criminal Damages scheme. Under the former, a determination of emotional distress was required for eligibility. This depended heavily on the opinions of psychiatrists who applied the diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Psychiatrists were employed as expert witnesses by both the plaintiff and the state, yet little consideration has been paid to the possible impact of these financial arrangements on diagnostic practice. There have been suggestions that psychiatrists in Northern Ireland have adopted the PTSD diagnosis much less frequently than their counterparts elsewhere in the UK. One might conclude that this might have assisted the state in limiting its expenditure on compensation, and would have had ramifications for its distribution. Thus, the determination of the existence of 'trauma' - its recognition, its manifestation in particular forms - or the lack of attention paid to it are influenced by financial, social, professional and political factors. Elsewhere (Smyth, 1998), I have discussed the issue of who 'qualifies' as a 'victim' in Northern Ireland. These matters are far from simple, and meaning is often contested. The use of the term 'trauma' presupposes a universality of definition of experience and effects. Yet, as mentioned above, what is described as traumatic in one set of circumstances might be regarded as inconsequential in another. Attempts to systematise a definition, through the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), have raised further problems as the origins and history of the PTSD category illustrate. In war and other chronic danger, combatants and civilians experience severe and persistent fear. Such fear is, predictably, greater for some. Those whose lives are in extreme jeopardy, such as combatants, are supposedly equipped by their training to find ways of managing high levels of fear. Others, not so trained or habituated, or who have particular sensitivities, may experience strong fear, even when facing lesser risk. Such severe fear produces a range of effects, variously described over the last century, arising from the experience of soldiers in the first world war and subsequent conflicts: 'cowardice', 'shell-shock', 'hysteria', 'malingering', 'commotional shock', 'soldier's heart' and 'disordered action of the heart'. After World War I, such conditions were dealt with by methods ranging from court-martial to psychiatry. The psychiatric approach was rather inconsistent and sometimes brutal. Sufferers could be treated by electric 'faradisation' at the hands of Yealland, or by the 'talking cure' advocated by W H R Rivers (Showalter, 1987). Hunter (1946) pointed out that the army was the patient, even though the individual soldier was being treated: the goal was to get the latter back on duty so that the war could be won. A fictionalised account of the associated moral and clinical dilemmas is provided in Pat Barker's novel, Regeneration. Young (1995) discusses the so-called DSM-iii revolution, when the Council on Research and Development of the American Psychiatric Association established a task force to take diagnosis towards a standardised classification of conditions. The DSM-iii, and subsequent editions of the manual, aimed to establish a research-based system of classification of diseases common to all theoretical orientations within psychiatry and psychology, tested in clinical trials and meeting validity challenges. None of the research, however, was conducted in societies undergoing conflict. War-related trauma entered the diagnostic system through a series of debates and struggles relating to the experience of Vietnam veterans: the PTSD diagnosis as it appeared in the DSM was based on their experience. The standard tour of duty in Vietnam was 12-13 months and most veterans served only one, though some did two or even three. Most returned between 1964 and 1975 but the PTSD diagnosis first appeared in 1980. This led to anxiety on the part of the authorities about the financial implications of providing treatment for service-related disorders, now including PTSD. Shorter (1997: 304) described these developments thus: In the years after 1971, the Vietnam veterans represented a powerful interest group. They believed their difficulties in re-entering American society were psychiatric in nature and could only be explained as a result of the trauma of war. In language that anticipated 'the struggle for recognition' of numerous later illness attributions, such as repressed memory syndrome, the veterans and their psychiatrists argued that 'delayed massive trauma' could produce subsequent 'guilt, rage, and the feeling of being scape-goated, psychic numbing, and alienation'. In early 1973, the National Council of Churches organised a First National Conference on the Emotional Needs of Vietnam-Era Veterans. Out of this grew a nation wide campaign to persuade recalcitrant psychiatric establishments to recognise the new disease. Once it became known how easily the apa's Nomenclature Committee had given way on homosexuality, it was clear that psychiatrists could be rolled. PTSD first appeared in the third edition of the DSM, replacing the earlier 'gross stress reaction', a passing response to intolerable stress. The DSM now specified that the stress should be 'outside the range of usual human experience' and be sufficient to evoke 'significant symptoms of distress in most people'. The DSM then listed symptoms: persistent and distressing re-experiencing of the traumatic event, dreams, flashbacks, intrusive images, numbing, avoidance of situations that trigger memories of the traumatic event, hyper-vigilance evidenced through sleep disorders, inability to concentrate, irritability and so on. PTSD was developed to deal with the reactions of soldiers who saw between 12 and 39 months of combat. It was also developed according to symptomatology that appeared after the soldiers were removed from the war zone, and where such symptoms and behaviour were clearly outside the population norm. Yet the PTSD framework is universally applied to conflicts such as that in Northern Ireland. Unlike the average tour of duty in Vietnam, in Northern Ireland exposure to conflict has lasted for almost three decades, which may well merit an examination of the applicability of PTSD as a framework in long-standing civil conflicts. The more recent differentiation between 'type one' and 'type two' trauma remains inadequate in the face of ongoing experience of violence. And the population of the region - particularly police officers and locally-recruited soldiers, paramilitary combatants and residents of militarised areas - have not left the 'war zone': this is not 'post-trauma' experience. Voluntary organisations offering support to those affected by the 'troubles' experienced a rapid increase in requests for help after the 1994 ceasefires in Northern Ireland and on subsequent occasions when the level of violence diminished. This suggests it is only in the post-conflict phase that the full psychological and emotional impact of armed conflict can emerge, yet help is also required while conflict continues. The diagnostic criteria for PTSD differentiate between acute and chronic forms. The appearance of the syndrome is correlated with the severity of the stressor (Kaplan and Sadock, 1988), with 50 to 80 per cent of those exposed to a devastating disaster suffering from PTSD. The incidence in the population is cited as being 0.5 per cent for men and 1.2 per cent for women. Onset can be from a week to 30 years, with about 30 per cent of patients recovering, 40 per cent retaining mild and 20 per cent moderate symptoms, and 10 per cent remaining the same or deteriorating. Diagnosis of PTSD in Northern Ireland is probably lower than might be expected in such a protracted violent conflict (Fay et al, 1999). The lack of respite from violence is one factor. Psychiatric diagnosis is the sole prerogative of psychiatry in Northern Ireland, unlike in the us where several professions may diagnose, and differences in diagnostic practice (mentioned above) may account for some of the difference. Furthermore, as already discussed, obtaining a PTSD diagnosis has been a prerequisite for compensation under the Criminal Injuries Compensation scheme for psychological and emotional injury as a result of the 'troubles'. The role of many in the psychiatric profession in assessments of litigants, as prosecution or defence witnesses, complicates the predominantly therapeutic remit of diagnostic practice. In a continuing conflict such as Northern Ireland, a diagnosis of PTSD will be given when the diagnostic criteria are met - assuming, as does the DSM, that experiences such as shooting and bombing are 'outside the range of human experience'. Yet for those living in the worst-affected areas, and for the mental-health professionals who treat them, militarisation, shooting, killing and bombing have been commonplace. This challenges the validity of such a diagnostic category in this context. Straker (1987) holds the view that PTSD is a misnomer where violence is ongoing, proposing instead 'continuous traumatic stress syndrome'. A further difficulty with the category lies with its origin in military psychiatry. Combatants' and soldiers' experience has played a defining role in the definition of a set of diagnostic criteria and concepts have then been applied broadly to civilians and combatants alike. In this field, as in many others, it is those with the power of weaponry and relationships with political leaders whose experience has been seen as the defining factor. Significant departures between civilian and combatant experiences seem likely: the relative powerlessness of civilians, for example, would suggest they might experience war and civil conflict differently. Yet none of this is clear in current conceptualisations. Similarly, age, gender and cultural differences in responses to violent social division are relatively unexplored, yet emerging evidence would indicate their existence (Fay et al, 1999). Two polarised views of trauma are indicated by PTSD and Straker's alter-native category. The latter sees the sufferer's context as the still violent society, the former as the consulting room - where the solution for PTSD is also seen as lying. Yet in many political conflicts, it is neither financially feasible nor socially desirable to offer clinical treatment to all those who suffer psychologically from exposure to violence. From the available evidence (Fay et al, 1999), relatively few require intensive and specialised psychological help. For others who may have symptoms of trauma, and who can be sustained within community and family networks, perhaps other group and community interventions can prove less stigmatising and more empowering. Yet even for those for whom this kind of intervention is appropriate, accessibility to such services (for civilians) is often difficult. It is a paradox of modern warfare that while provision is often made by armed parties for the care and psychological rehabilitation of their members, that for the overwhelmingly civilian victims is often scant.  It's not over The mental-health professionals have from the outset been divided in their approach to PTSD and its antecedents. Rivers' 'talking cure' versus the shock treatment of Yealland is still reflected in debates today, albeit in less extreme form. The psycho-dynamically inclined tend to the view that exploration of the experience through talking - telling and retelling the story of the trauma - will 'wear it out' and achieve therapeutic results. Those of a more behavioural bent favour instead a 'reprogramming' to extinguish unwanted or dysfunctional responses. Other treatments, ('eye movement desensitisation régime', for example) offer seemingly technical solutions which focus on apparently unrelated issues such as eye movement. In the community, debates about remembering the past have involved those who have been bereaved and injured 'telling their stories' to raise awareness of the suffering of those who have been hurt. The consumption by the media and the publishing world of 'fight and tell' biographies of former IRA, SAS and other combatants, and of those who have been bereaved or injured, is indicative of the 'market' for story-telling. While these various forms of narrative can, on occasion, be socially valuable, and personally assist the 'story teller', there is cause for caution. The teller may be trapped in an identity which inhibits whatever personal resolution might be achieved. Moreover, while the focus of the story may be humanitarian - as what the market 'wants' - rather than on any political context, the teller may be caught up after publication in a maelstrom of political claim and counter-claim. This is not a process conducive to good mental health. A further area of concern is the role of psychotropic drugs in 'treating' the distress associated with trauma. Many were shocked last year by a scene broadcast from Russia, where a woman bereaved through the wreckage of a nuclear submarine was injected with a tranquilliser - in full public view - after she expressed her anger at a senior politician. Yet more subtle and hidden forms of such medication have been provided in Northern Ireland for almost three decades. Evidence from South Africa suggests that drug companies regard the medication of, for example, adolescents diagnosed with PTSD as a worthy investment in research on the application of (exclusively) chemical intervention. Yet these adolescents have been traumatised in political violence and live in violent environments. This may present a new market for pharmaceutical companies; it may not, however, appear socially or morally attractive to the rest of us. Finally, human-service professions have been hesitant to acknowledge the political aspects of work in this field. Distrust, partly stemming from this reluctance, has meant little open exploration of new and creative ways of supporting those who have suffered. A range of solutions must be found and made available, and no one method will serve all. This, however, will require a multi-dimensional and multi-disciplinary approach, based on mutual respect between political actors, professionals and communities. A first step might be working to establish that respect. Bibliography Barker, P (1992), Regeneration, London: Penguin Books Bloomfield, K (1998), We Will Remember Them: Report of the Northern Ireland Victims Commissioner, Sir Kenneth Bloomfield, Belfast: Stationery Office Crawford, C (1999), Defenders or Criminals? Loyalist Prisoners and Criminalisation, Belfast: Blackstaff Press Fay, M T, Morrissey, M, Smyth, M and Wong, T (1999), Report on the Northern Ireland Survey: The Experience and Impact of the Troubles, Derry: University of Ulster and INCORE Giddens, A (1993), The Transformation of Intimacy: Sexuality, Love and Eroticism in Modern Societies, Palo Alto: Stanford University Press Hunter, H D (1946), 'The work of a corps psychiatrist in the Italian campaign', Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps 96:127-30, cited in C Garland (1998), Understanding Trauma: A Psychoanalytic Approach, London: Duckworth/Tavistock Hynes, S (1997), The Soldiers' Tale: Bearing Witness to Modern War, London: Pimlico/Random House Kaplan, H I and Sadock, B J (1988), Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences Clinical Psychiatry, Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins Little Oxford Dictionary (1969) (fourth edition), Oxford: Clarendon Press Oxford American Dictionary (1986), New York: Avon Books Shorter, E (1997), A History of Psychiatry, New York: Wiley Showalter, E (1987), The Female Malady: Women, Madness and English Culture 1830-1980, London: Virago Smyth, M (1998), 'Remembering in Northern Ireland: victims, perpetrators and hierarchies of pain and responsibility', in B Hamber (ed), Past Imperfect: Dealing With The Past in Northern Ireland and Societies in Transition, Derry: University of Ulster and INCORE Smyth, M, Hayes, P and Hayes, E (1994), 'Post traumatic stress among the families of those killed on Bloody Sunday', proceedings of Northern Ireland Association for Mental Health conference on violence, Belfast Straker, G and the Sanctuaries Team (1987), 'The continuous traumatic stress syndrome: the single therapeutic interview', Psychology in Society 8: 48 Young, A (1995), The Harmony of Illusions: Inventing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, New Jersey: Princeton University Press Thomas, L M (1999), 'Suffering as a moral beacon: blacks and Jews', in H Flanzbaum (ed), The Americanization of the Holocaust, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins