CAIN Web Service

Independent InterventionMonitoring the police, parades and public order

A Purpose and responsibilities Stewarding fulfils two interrelated purposes:

Internal controls Organisers of parades, demonstrations and protests normally have clear ideas of the messages they want to convey through their event. They may therefore impose restrictions on who may take part, what banners or slogans are displayed or how participants behave, by using the stewards to monitor and react to what is taking place. Equally, it is crucial for those seeking to organise public entertainments to control their events in a way that will guarantee success. This may be done by ensuring that people pay to spectate, as with a concert or sporting event, or that participants get maximum enjoyment, as with a parade or carnival. Some form of stewarding is therefore vital for the control of all public events. It is inconceivable that any large public event could be organised without the organisers developing some way of managing the event to their satisfaction. Although the internal control of an event is usually defined by the organisers themselves, there are examples where external bodies have been required to intercede. Attempts by lesbian and gay groups to participate in the St Patricks Day parades in both New York and Boston were opposed by the organisers. Eventually the Supreme Court ruled that the organisers had the right to determine who should and should not be allowed to participate (Jarman, Bryan, Caleyron & De Rosa 1998: 86-90). While the police had the responsibility to control the public protests by the excluded groups, the organisers retained the responsibility for stewarding the parade. External obligations The US example illustrates the fact that all public gatherings take place within the context of social responsibility and a framework of national and international law. This context encompasses areas as diverse as health-and-safety regulations and human-rights legislation, as well as more a general responsibility to the communities, including residents and businesses, that willingly or unwillingly become effective hosts of the event. While in some senses national law defines and institutionalises the responsibilities that organisers of events have towards society, these responsibilities often extend beyond those specified in law. Organisers have a moral as well as a legal obligation to the communities in which they are holding events. For example, the organisers of the Notting Hill Carnival in London have clear legal obligations which are defined by public-order legislation and health-and-safety regulations, but beyond that they would accept an obligation to the people who live in the Notting Hill area. This may involve compromising on what had been regarded as some of the fundamental aspects of the carnival. Informal agreements and restraints have been arrived at on such things as the route of the carnival and when the very loud sound systems are closed down in the evening. Such agreements are then policed by stewards and monitored by officials. The role of stewards The role of stewards is largely defined by the organisers of an event, although there are always legal limitations placed on individuals as to how they handle people in the course of their work. However, it is not always clear where the organisers define the limits of their event. For instance, the Orange Order tends not to regard spectators as part of it; instead they are often described as hangers on and are therefore not seen as the responsibility of the organisers. In contrast, over recent years football clubs have come to recognise that spectators are part of their responsibility and have increasingly accepted the need to manage that part of organising a match. The differences between a parade and football match are in part due to the ease of recognising who is a spectator and who is a passer-by. However, crowds of interested spectators are as much a fundamental feature of most parades as they are of sporting events and the behaviour of spectators is often influenced by the events they are watching. A more complex situation arises when one considers the role of stewards in terms of the external relationships. Organisers of entertainment events are usually obliged through a system of licences and health-and-safety legislation to provide a minimum level of stewarding, but organisers of parades, demonstrations and protests do not have such clear-cut obligations. Providing adequate stewarding is not regarded as a general responsibility in law. This is partly because a duty is placed on the state to facilitate freedom of assembly and to keep public order, and therefore effectively to manage the event. This is most obviously manifested in the provision of police officers with the responsibility for general crowd control. While the responsibilities of stewards towards participants are defined by the organisers, their obligations to those not directly taking part are far more problematic and by implication suggests an exploration of the role and definition of policing. Policing can be narrowly defined as those activities conducted by police officers, but policing can also be viewed as a n activity conducted within society in general and not restricted to a specific institution. As such, a community watch scheme may perform a policing function while not being an institutionalised police force. Similarly, stewards perform a policing function. Consequently relationships between stewards and the police are not always easy. Stewards carry no legal powers other than that of an ordinary citizen. Nevertheless, while stewards do not have the same legal authority as police officers, it may well be that they have greater legitimacy with those taking part and this effectively gives them more control. On the other hand, because stewards draw their legitimacy from the organisers of an event they are not usually suitable for dealing with some of the external relationships, particularly when an event creates either antipathy or opposition in the area where it is taking place. Stewards can play a significant role in the policing of an event but the nature of this role will depend on a number of factors. These include their abilities, training and organisation, the resources available, and the degree of trust and liaison established between organisers and the police. Developing more responsible stewarding can be valuable in a number of ways. It can reduce the need for police resources, increase community involvement and empowerment, and help develop the skills and confidence of the stewards themselves. We will illustrate some of these points with a brief review of some examples. Some case studies Case studies from around the world reveal the widespread recognition of the role that stewards can play but also of the associated problems they can create. In a number of countries, the authorities place a range of responsibilities upon organisers of public events which imply a responsibility to provide sufficient stewards to exercise control. In France, for instance, groups organising demonstrations are expected to provide their own stewards, even though it is not a legal requirement. However, such informal relationships have been put to the test by the right-wing Front National, which caused concern among police and political opponents when it began to provided stewards in police-style uniforms. In Italy, organisers are similarly expected to provide stewards and many of the larger trade unions have developed a comprehensive system to reduce the need for the police presence at their demonstrations and protests (Jarman, Bryan, Caleyron & De Rosa 1998). In both these cases, the stewards take primary responsibility for controlling their own members while the police have responsibility for protecting and facilitating the demonstration. South Africa We discussed earlier the use of independent monitors at demonstrations in South Africa during the transition to democracy; during this period, marshal training programmes were also developed in a number of areas (Elliston 1996). This was made possible by the limited co-operation through the National Peace Accord of the ANC, the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) and the South African police force, (including the widely hated internal stability units responsible for crowd control), as well as the involvement of various observer missions and European police officers. Marshals were trained in a range of subjects, including peacekeeping and human rights, the roles and responsibilities of marshals, crowd management and dynamics, event planning, communication, problem solving, evidence gathering, fitness and training skills. Elliston argues that the training immediately increased the sense of responsibility that organisers felt, particularly vis-à-vis such issues as disruption to the life of the community. It also allowed for improved planning and communication with the police and, as a by-product, participants began to display greater political tolerance to other organisations and started to appreciate the difficulties others had in controlling their events. Elliston concludes by suggesting that such projects may in turn help to create a culture of community policing (Elliston 1996:168-169). Football Grounds Problems surrounding football crowd violence in the 1970s and 1980s (as well as a number of high profile disasters which resulted in death and serious injury to spectators), increased awareness of public-order and health-and-safety issues surrounding sports events in England and Scotland. This resulted in a comprehensive system of stewarding for all major sporting venues. The use of trained stewards within football grounds has meant a siguificant reduction in the need for police officers there. Even at highly contentious matches, such as those between Celtic and Rangers in Glasgow, the level of policing required in the ground is relatively small. In part, this situation has been encouraged by legislation requiring football clubs to ensure public safety inside the stadia and to pay for the police presence there. Training and paying stewards comes cheaper. Many of the clubs also arrange to have stewards travel with fans to away games, to reduce the chances of disturbances in transit. Notting Hill Carnival Carnival-style events are possibly the most difficult to steward. For many people the carnival is about the absence of control, about people claiming the streets and about the normal structures of society being overturned. The Notting Hill Carnival, held in west London every August bank-holiday weekend, has in the past been an arena for confrontation between the police and people in the black community. During the 1990s, however, a modus vivendi has been developed between police and organisers, which has significantly improved the environment in which the event takes place and the public perceptions of the weekend. This has led to increasing numbers attending the carnival, and for two days the largely residential streets of North Kensington are packed with hundreds of thousands of people. One aspect that police and organisers have been keen to develop has been crowd safety and stewarding. The large carnival floats, which have to negotiate awkward corners and the crowds of people who throng the streets along the three-mile circular route, create a significant safety problem. Good stewarding should mean that there is less need for highly visible policing and the safety of all those taking part can be increased. In 1998 the carnival organisers employed 128 people to work as stewards over the carnival weekend, responsible for crowd management. The stewards work in teams in designated areas and liaise with the relevant police officers in their area. In addition, there are 66 people employed as route managers, responsible for the movement of the carnival procession through the crowd. While the route managers seem to work fairly effectively and efficiently, the quality and training of stewards is a problem which the carnival organisers do not feel they have yet solved. Issues such as whether it is better to use local people or to hire disinterested outsiders are among the factors that have been discussed. Different interest groups within the carnival also have their own particular concerns, such as the organisers of the costumes and floats who may require special protection from the dense crowds for the performers. Simply finding the funding for adequate stewarding is very difficult. A study commissioned by the Notting Hill Carnival Trust recommended that they should employ 1,000 public-safety assistants to cover all aspects of the carnival, but as this would cost over £200,000 each year it will not be possible unless a specific source of funding is identified. So whilst it is recognised that good stewarding is an important part of facilitating the carnival, the funding, training and organising of stewards remain problematic.

Stewarding in Northern Ireland The wide range of political, commemorative and social parades, the frequent organisation of protests, and the large following for football, rugby and Gaelic games means that stewarding is an everyday occurrence in Northern Ireland. However, contemporary divisions bring contrasting practices. For example, the lack of acceptance of the RUC within the nationalist community has partly been responsible for the development of extensive crowd-management arrangements at Gaelic Athletic Association grounds and at Derry City Football Club, which allow events to take place with almost no police involvement. In contrast, Irish League football, although using stewards, largely relies on the RUC to control crowds. Similarly, political circumstances have meant that for many nationalist events, crowd-management functions have largely been undertaken by organisers, whereas loyal-order parades have relied more heavily on the RUC. Nevertheless, loyal-order parades, particularly the larger ones, require a lot of organisation and this involves the various orders providing stewards. The stewards focus mainly on the internal control of the event. One of their principal roles is to keep spectators away from the road and they have a reputation for being over-zealous and rather aggressive if people try to cross the parade. The quality of stewarding at parades events varies considerably. The work done by members of the Orange Order to control the crowds at Drumcree and on the Ormeau Road in Belfast in July 1999 showed how valuable effective stewarding can be in ensuring that events pass off with the minimum of disruption. However, at many such events the best that can be said is that the stewarding is well meaning but ineffective; all too often the stewarding has been appalling, seeming to be more trouble than it is worth. There has been little or no training for stewards, so the stewarding relies heavily on the experience of the organisers and the personal qualities of those undertaking the role. In addition, in both loyalist and republican areas, paramilitary groups are involved in stewarding events, drawing not only upon their legitimacy within the local community but also, as with the RUC, on their ability to wield, or to threaten, physical force (Jarman forthcoming). Experience at many political demonstrations and protests, but more particularly at loyal-order parades, indicates that stewards are often not clearly visible, appear unable to deal with behaviour deemed inappropriate by the organisations they represent, use only minimal forms of communication and have underdeveloped or conflictual relationships with the police. This has meant that the police often have little confidence that organisers can deliver on agreements over the events and the stewarding is more symbolic than functional. The style of policing used by the RUC is highly militarised and routinely relies upon a very large deployment of resources; the widespread inability of parade organisers to provide adequate stewards to control their own events can provide ajustification for this. Apprentice Boys of Derry Steward Training Project While it is clear that good stewarding cannot solve the fundamental problems of providing a safe and secure environment for people to mount public events in Northern Ireland, it is one part of the solution. We raised the issue in our 1996 report (Jarman & Bryan 1996:125) and the role of stewards was then taken up in the Independent Review on Parades and Marches in 1997. Their report recommended that the Parades Commission should pay close attention to stewarding and take such steps to improve standards of stewarding in both parading and protesting organisations as it deems necessary (North Report: 13.54). This recommendation was subsequently adopted by the commission and has been written into its code of conduct, introduced in 1998. This says that organisers should take care to ensure that a sufficient number of trained stewards are present at events, that those stewards should be clearly identifiable by members of the public and that stewards should also have an effective means of communication with each other and with the event organisers. One initiative to try to overcome these very difficult problems took place last year in Derry, in the organising of the Apprentice Boys parades in August and December. The Relief of Derry parade, in mid-August, has been the centre of particular controversy since 1995 when Derry City Council reopened the walls and the Apprentice Boys of Derry applied to take what, until 1969, had been the customary parade route around the walls. While the debate over this parade shared some of the features associated with parades disputes in other parts of Northern Ireland, there were some significant elements that suggested that improved stewarding could provide part of the solution. Few people, if any, in the nationalist community questioned the right of the Apprentice Boys to hold public events in a city, which is clearly of enormous historical and symbolic importance to the Protestant community. There is a clear commitment to the wellbeing of the city among a wide range of groups including the local Apprentice Boys, the Bogside Residents Group, Derry City Council and representatives of commercial interests. Many within the nationalist community are sensitive to the reduction in the Protestant population on the west bank of the Foyle and the sense of siege that the remaining community, based in the Fountain area, feels itself to be under. A significant aspect of the dispute in Derry has been the anti-social behaviour of some of the participants in the parade. This has been most problematic in sensitive areas, such as those parts of the walls overlooking the Bogside, and in the commercial centre, especially near the war memorial in the Diamond. The problems are accentuated because of the size of the parade (it is the largest loyal-order parade of the year, with up to 150 bands taking part). Also, because many of the participants are not from the city, they are unfamiliar with it and treat it with a degree of hostility. Furthermore, even by the standards of other large loyal-order parades, there is a considerable consumption of alcohol during the day In recent years the parade has always required a large police operation, the more so as protests have been organised by the Bogside Residents Group. Since 1995 there has been a range of engagements between interest groups in the city. These have included a series of mediated processes, some face-to-face meetings and the development of a City Forum which all parties have attended. Relationships have at times been fraught but have never broken down to the extent that they have in other areas where there are similar disputes. In addition, unlike the Orange Order, the Apprentice Boys of Derry have been willing to engage with the Parades Commission. They have also made a clear attempt to develop the August parade into a more open and accessible event: they have introduced a pageant before the opening parade around the walls and in 1998 they ran a festival in the preceding week. In the autumn of 1997 a consultancy group presented a feasibility study to the Parades Commission on the possible development of steward training. The group included a trainer with wide experience in training stewards for Premier League football clubs in England and a consultant on policing issues who had developed a marshal training project in South Africa under the 1992 peace accord. Its study highlighted some of the obvious benefits of good stewarding:

The proposed training scheme had additional benefits, including the possible development of a National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) based on a course already being run in England. The project was developed in conjunction with members of the Apprentice Boys and with the assistance of police officers in Derry. It was funded by the Parades Commission and the Community Relations Council. The training examined:

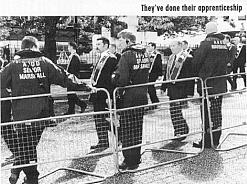

Training initially took two evenings a week over ten weeks. This was followed by a six-month assessment of the stewards, before, during and after their involvement at parades. Thirteen members of the Apprentice Boys completed the training, seven being assessed to NVQ level. In addition a range of equipment, such as tabards and walkie talkies, was obtained for use by the stewards at parades. The Relief of Derry parade in August 1998 was a tense occasion, partly due to the problems at the previous parade and partly because the dispute over the Drumcree church parade in Portadown had not been resolved. Nevertheless, a compromise was reached between the Bogside Residents Group and the Apprentice Boys. This included an agreement that the main parade in the afternoon would not involve a complete circuit of the Diamond while the residents group in turn cancelled its protest. The pageant in the morning went well, although there were a few minor problems during the ceremony at the war memorial. However, the main parade in the afternoon was very confrontational, as crowds gathered on both sides of the Diamond. The police had attempted to keep their presence to a minimum but as numbers grew on both sides, first abuse and then bottles were exchanged. The day ended with running battles involving the police and people from both communities, and at one point an officer was forced to fire warning shots to protect another officer who had become isolated from his colleagues and was being attacked. In spite of the violence that marred the end of the day, there is no doubt that improved stewarding made a difference. Liaison and planning between the police and organisers was greatly improved on previous years. The Apprentice Boys stewards only dealt with those participating in the parade and members of the Protestant community who came to support the event. They were aware how to liaise with the police involved with the operation but they had no involvement with the nationalist crowds. Stewards remained at the Diamond in what were often very difficult circumstances. They tried to control rowdier elements within the crowd and to ensure that the bands respected the war memorial by remaining silent as they paraded through the Diamond. While in many respects the stewarding operation failed to maintain control of the parade in key areas, there was general recognition that the organisers had made significant steps to try to ensure that the parade remained peaceful.

The steward-training programme has provided a number of people with both crowd management skills and a formal qualification. It has given them more confidence in the skills they possess and has started to develop an improved liaison between the police and event organisers. In the short term, the project did have some benefits in the attempt to control what can be a very difficult event. Anecdotal evidence suggests that matters could have been a lot worse but for the constructive role the stewards played. The aim of such training programmes must be to empower people organising events to be in a position, through the possession of skills and resources, to be able to manage their own events. This in turn can raise the confidence of representatives in communities when negotiating relationships between communities and with the police. However, it will take time to judge whether the development of steward training will have long-term benefits for organising events in the city. There was again serious violence in the aftermath of the demonstration in August 1999. Other groups have already shown interest in the project and, resources permitting, it is hoped that training courses could be repeated. At the very least, those who have been through the training have become a resource in themselves, in so far as they will be able to pass on their knowledge to other members of the organisation who wish to become stewards. At present, steward training in Northern Ireland is done in an ad hoc manner, neither planned nor sustained. In spite of the clear need for good stewarding at political events and public entertainments, no educational or training institution offers courses in the subject. The lack of a long-term commitment to such skills training stands in stark contrast to the millions of pounds spent on policing public order in recent years. More imaginative resourcing is clearly required if stewarding is to become part of a solution to such problems.

Democratic Dialogue {external_link} |