CAIN Web Service

No FrontiersNorth-South integration in Ireland

Robin Wilson F our years ago, in his submission to the Forum for Peace and Reconciliation in Dublin, the economist John Bradley declared (Bradley, 1995: 74,: "It must be stressed that a situation of separate policy development between North and South is rapidly becoming artificial and outdated." In an equally pithy comment, he had earlier written that, because of the scale of the Westminster subvention to Northern Ireland, unification was not "economically feasible" though if the north, utilising the potential of devolved power to enhance economic development, were capable of sustained out-performance of the rest of the UK such that the subvention gradually diminished, that economic barrier would be removed over time (Bradley, 1994).These two comments are indicative of how the policy debate on north-south relations has moved on since 1974: the emphasis now is on looking beyond ideologically-driven support for, or resistance to, north-south integration, towards what works in order to pursue it to maximum advantage. Some constitutional reflections explain why. At the heart of the Sunningdale syndrome identified in the introduction was an ideologically-driven polarity, ultimately to prove the Achilles heel of the power-sharing arrangements. On the one hand was the Ulster Unionist chief executive, Brian Faulkner, for whom the north-south dimension was simply "necessary nonsense" to appease nationalist demands. On the other hand was the Social Democratic and Labour Party, whose goal as described by Paddy Devlin was all-Ireland institutions which "would produce the dynamic that could lead ultimately to an agreed single state for Ireland" (Bew and Gillespie, 1993: 73-4). Yet both unionist fears and nationalist hopes were overblown. As memoirs from key northern civil servants now indicate, jurisdictional jealousies on both sides of the border famously confined the areas officials were prepared to see transferred to the Council of Ireland to "sacrificial ewe lambs" (Hayes, 1995: 1974). And, when Mr Devlin arrived late at a Sunningdale conference session to hear the then foreign minister of the republic, Garret FitzGerald, "well launched upon a characteristically visionary exposition of a potential Council of Ireland with wide-ranging executive responsibilities for this and that", before even sitting down the health minister designate told him "you can keep your hands off my f...ing ambulances for a start" (Bloomfield, 1994: 191). Finally, the key official in Dublin at this time recounted in later years to the author how, in 1974, Mr Faulkner had come to plead with the taoiseach, Liam Cosgrave, to forego the Council of Ireland to save the tottering power-sharing executive. Remarkably, the official said that the taoiseach would have been willing to comply had it not been impossible at that stage to do so. Asked how the republics government could have countenanced surrendering such a major political gain, he explained that, had all the functions which theoretically could have been transferred to the council under the Sunningdale agreement been so transferred, they had calculated it would have required 44,000 civil servants from the two jurisdictions to staff it. Ideology was one thing, it was evident, but the mandarin mind simply quailed at the prospect of such a giant quango. But if ambitions have to be more sanguine 25 years on, there is no doubt the potential for closer integration is at the same time significantly enhanced indeed, in the long run, almost limitless. Key to this has been the patient work of many over the years on the ground (much of it assisted by Co-operation Ireland), building trust and undermining fears notably via the business confederations, IBEC and CBI, and their Joint Business Council. Crucial now is the Belfast agreement, which begins to supply the institutional architecture under which north-south integration can flourish. Two possible scenarios loom in the years, even decades, ahead. One is a malign one, in which the machinery of north-south integration is gummed up by political mistrust, such progress as there is is confined to track one officialdom and to business co-operation, and little materialises amidst widespread popular suspicion and/or disengagement. There are negative political spillovers into the viability of the internal political institutions in Northern Ireland, as nationalists become increasingly restive at unionist reticence. The Sunningdale syndrome continues to be active. The benign scenario is the opposite. Here, the involvement of numerous actors ensures synergies between the different levels of integration, and positive spillovers from one domain to another. The commitment to the enterprise, led from the top, oils the wheels of the machinery and minimises friction. Growing trust relaxes unionists attitudes to the island-wide imagined community so crucial to nationalists, leading to positive political spillovers vis-à-vis the legitimacy and stability of the institutions within Northern Ireland (Teague, 1997). The Belfast agreement is premised on the benign scenario. In doing so it takes us beyond the widespread assumption that north-south integration is really creeping unification. Consideration of the situation in Scotland may help bring a more profound understanding. On the eve of the first elections to the Scottish Parliament in May 1999, the leading analyst Lindsay Paterson suggested at a seminar in Edinburgh that the will-Scotland-become-independent? question that had marked the devolution process (on both sides) might turn out, in the long run, to be the wrong question. The strength of the Scottish National Party meant the question would not go away, Prof Paterson insisted. But a Labour-led administration at Holyrood would not sue for divorce from a Labour (or, eventually, Labour-led) administration at Westminster. Thus the question would only, in reality, be put as and when in the next century a non-Conservative majority in Edinburgh faced once more a Conservative government in London. But, by that time, the key powers reserved to Westminster over macroeconomic policy, defence and foreign affairs might well have been transferred to Brussels , via economic and monetary union and the outworkings of the Kosovo crisis. In which case, Westminster and Whitehall would just be another set of external institutions with which the Edinburgh parliament would have to deal. What, then, would independence versus the union actually mean? By the same token erosion of Irish neutrality via prospective membership of NATOS Partnership for Peace and the progress towards a common EU foreign and security policy, allied to involvement of the republic in EMU from the outset, will reduce the political differential between a sovereign parliament in Leinster House and the new assembly at Stormont. Meantime, the experience of devolution UK-wide will remove the day-to-day Northern Ireland political agenda from Westminster oversight and engagement. As under the old Stormont régime, therefore though, hopefully, not with the same malign consequences the region will become in geo-political terms essentially self-governing. And, in that context, it will in effect be able to develop, politically, such relations with the republic as it wishes (financial constraints, importantly, permitting). Meanwhile, since there can not be a border poll under the Belfast agreement, to change or confirm the constitutional position of Northern Ireland, until such times as the secretary of state decides it is likely to lead to a majority for change, a referendum can not be anticipated in the region until even later than a similar vote in Scotland. In which case the conventional, adversarial ideological wrangle as to whether or not Northern Ireland is on a slippery slope (as unionists have feared) to Irish unity and independence (as republicans have hoped) might itself be best consigned to history, along with the violence it has spawned. One leading SDLP figure has already manifested the political courage to indicate at an unattributable conference that he felt quite relaxed about the current constitutional arrangements remaining "indefinitely". Such gestures away from old ethno-nationalist positions are very helpful in removing ideology, as well as guns, from Irish politics, and dispelling the Sunningdale syndrome. A similar ideological lightening-up on the part of unionists ever-vigilant about absorption into an Irish identity would be highly desirable. What perhaps the future holds is a political formation of a new type, in which Northern Ireland is able to exploit the increasing diffusion of sovereignty and permeability of borders to maximise its autonomous potential and its diversity of external relations with the rest of Ireland, the rest of the UK and the rest of Europe. It is what the German sociologist Ulrich Beck would describe as an instance most obviously symbolised by the fall of the Wall of the late 20th centurys replacement of the politics of either/or, by the politics of and (Beck, 1997: 1). The recognition in the Belfast agreement that citizens of Northern Ireland can be "Irish or British, or both [my emphasis], as they may so choose" (Northern Ireland Office, 1998: 2) is an important step in that direction. In that context, north-south integration can be re-envisaged in a genuinely non-threatening fashion as a principled but pragmatic effort, through co-operative endeavours from which all can gain, to build reconciliation across the island and enhance political stability. f the context of north-south integration has changed since 1974, so too has its nature. For a further significant shift has been the widening of the concept of government to governance. The Sunningdale model assumed government to be an essentially executive process confined to the political class. The Council of Ireland it envisaged was thus a centralised as well as top-down structure and clearly implicit in the division of its functions between the consultative, the harmonising and the executive was a process of movement from first to last. It was a structure, in other words, as the republics foreign minister, David Andrews, was (anachronistically) to declare during the talks leading to the Belfast agreement, "not unlike a government". Nowadays, it is clear that governance is a much more complex and differentiated process, which necessarily involves drawing upon a range of non-governmental actors, both for policy input and for policy delivery. This implies discrete executive (or implementation) bodies, not an embryonic all-Ireland state, and indicates that executive action is only part of a much broader spectrum of interventions likely to include governmental brokerage of, and assistance to, non-governmental networks in an environment of across-the-board, north-south policy co-ordination. This relates to wider EU trends. European directives have moved away from a harmonising approach across member states towards a more pragmatic emphasis on mutual recognition amongst them, thereby avoiding the waste of effort trying to unify disparate administrative arrangements entails. Paul Teague thus argues that there is neither much scope nor need for north-south harmonisation (Teague, 1997: 179): "Encouraging policy co-ordination does not necessarily mean the creation of all-Ireland institutions but it does require closer policy communities to be established between the administrations in Dublin and Belfast. At present the policy contacts between the two administrations across a wide range of government functions are not of the frequency or depth to allow for the full exploration of all possibilities for co-ordination." Indeed, the EU can play a substantive role in this regard. The former commission president, Jacques Delors, once indicated to the author in private conversation how much he wished to see north-south integration progress in Ireland. And Teague argues (Teague, 1997: 190-1): "When seen from this perspective, it becomes clear that the EU could play an important role in building all-Ireland policy and economic connections largely because many of its programmes and policies actually set out to facilitate, enable and improve collaboration across nation states." What is intriguing in this regard is the comment by Moray Gilland about how the EU is moving to rationalise the fearsome administrative complexity identified by Thomas Christiansen. In particular, the suggestion that cross-border and trans-national programmes should be woven into one new initiative and that trans-national bodies could be supported by the EU offers a tantalising prospect of how the otherwise obscure question of the relationship between the North-South Ministerial Council and the European Union could be resolved. (By using the word trans-national here, there is no intended implication that Ireland is not, in some sense, a national entity the author has an Irish passport. It is simply in the EU usage of trans-member-state.) The agreement refers (strand two, §17) to arrangements being made to ensure the views of the NSMC "are taken into account and represented appropriately at relevant EU meetings". But of course the union is based on the member-states, so whatever views the NSMC might have could, as things stand, only be conveyed to meetings of the Council of Ministers, for example, via the representatives of the UK or the republic. This would be likely, in practice, to mean the governments in Dublin and London coming to a policy agreement to express a common view. Looking to the future to the next treaty-making intergovernmental conference the option should be considered of adding a protocol to the treaty giving formal recognition within the union to such trans-national arrangements as the NSMC, in line with the evolution of Maze Europe. This would itself be encouraged if the NSMC were seen to be offering a viable model for the rest of the EU. That in turn would depend on the seriousness of the input to it: a vibrant assembly European committee, liaising with the Oireachtas Joint Committee on European Affairs, would be indispensable. A s Rory ODonnells chapter makes clear, EU experience shows it is crucial, if north-south institutions are to work, that they engage non-governmental expertise. Meanwhile, Hugh Frazer argues that there is a need for the broadest social ownership over the integration process. And there is a wider worry about existing north-south relations conducted at a non-governmental level being hoovered up into the NSMC and the implementation bodies.For all these reasons the case for a north-south consultative forum, only tentatively made in the Belfast agreement, is a compelling one. But to marry the demands for specialist input and inclusiveness, such a forum needs to be organised in a flexible manner which encourages deliberation and dialogue with officials. An effective committee system would therefore be crucial, as well as a facility for working groups capable of co-opting external expertise. More sophisticated politicians will recognise the benefits such an engagement can bring, as with the Civic Forum in the north. Indeed, one potential minister in the Northern Ireland executive recently modestly declared to an audience of NGOs involved in north-south collaboration: "Were starting much further back down the track." As Anderson and Goodman (1997) succinctly present the vision, "the re-creation of an all-Ireland civil society, though without political reunification in traditional nationalist terms, is now firmly on the political agenda". A month after the round-table in Monaghan, representatives of the principal social partners in Ireland issued an important joint statement on north-south co-operation in a European context (ICTU and IBEC/CBI, 1999). Prepared by the IBEC/CBI Joint Business Council and the Irish Congress of Trade Unions, it said: "The social partners support the establishment of an independent consultative forum which may be considered by the two administrations under the Belfast Agreement. We believe there are clear benefits in having a round table to review progress, identify issues, opportunities and problems which could be addressed by the North-South Ministerial Council and help to develop a co-ordinated and strategic approach to co-operation to mutual advantage." This is an encouraging development. In the past, the north-south impetus has mostly come from the business community. Nothing wrong with that, but in the future there is a need to ensure a more balanced involvement of the social partners and as large a commitment to questions of unemployment and exclusion as growth and prosperity. If this civic input from below is essential, horizontal north-south policy networks, which make this all-Ireland civic society a reality, are the other, equally important, side of this coin. Democratic Dialogue and the other participants in this project will continue to pursue this network construction themselves, like the many other organisations whose work Dominic Murray has so laboriously catalogued. Encouragingly, there has been an increase of nearly half in the recorded number of bodies with a north-south dimension to their work since the first edition of his inventory four years earlier (Murray, 1999: iv). A good example of such a network is the Standing Conference for North/South Co-operation in Further and Higher Education, which has thrown up a raft of policy ideas in this arena, such as student exchange arrangements, postgraduate bursaries for north-south projects, pump-priming for north-south research partnerships and so on (Standing Conference, 1998). This is an agenda that the new Centre for Cross-Border Studies, based at the Queens campus in Armagh, will, among other things, be able to develop. The orientation of the new implementation bodies and the NGO networks should be a problem-solving one, with a view to social learning. That is to say, leaving behind the grandiose ideological arguments about whether north-south integration is really a Good Thing or what the ultimate destination might be, the approach should be open-minded and willing to learn from experience. Such pragmatism is by far the likeliest approach to engage individual citizens in the process, as well as quelling suspicions and doubts. Rob Meijers remarkable comment that up to 150,000 Dutch and German citizens have some engagement with EUREGIG very year is testimony to what can be achieved, in terms of embedding a process of integration deeply within the wider society. B ut what is all this co-ordinating and networking for? Remarkably little literature has been generated over the years, especially from the northern parties, on the substantive agenda of north-south integration even co-operation. This may seem bizarre, given how much political grief the issue has caused; yet there, in fact, lies the explanation. It is precisely because of the hyper-political fashion in which this issue has been addressed that there has been so little recognition of the need to detail its social, economic and cultural outworkings.But now, for the first time, in addition to the Belfast agreement, developments in the republic may play a key role in setting that agenda. It has become a cliche, in the 90s, to refer to the Celtic Tiger economy (Sweeney, 1998). But, as James Wrynn (1998) has argued, "the Celtic Tiger, despite its sleek coat, squats in a shabby den". As Patricia ODonovan of the ICTU spells it out, (ODonovan 1999), "While Ireland is now close to EU average income per capita, it is many decades behind EU standards of public transport, public services and social infrastructure." Growing labour shortages and worsening congestion are testimony to the need to expand investment in childcare, education, training and transport (never mind the need to address spiralling house prices), if the Tiger is to continue to roar. The remarkable fiscal buoyancy the state enjoys as a result of this decades vertiginous growth can now be deployed to bring about an infrastructural revolution to translate that economic prosperity into a quality of life more akin to the European standard. The Economic and Social Research Institute has recommended a major, seven-year programme, including a north-south perspective (Fitz Gerald et al, 1999). As the Labour leader, Ruairi Quinn, has argued, it makes no sense to pursue such a great project except in an island-wide context (Irish Times, May 15th 1999). And there are cross-border elements in the Draft Regional Strategic Framework for Northern Ireland (Department of the Environment, 1998), expected to be matched in the forthcoming National Development Plan in the republic in particular, the Derry-Letterkenny area is likely to be identified as a common development node.

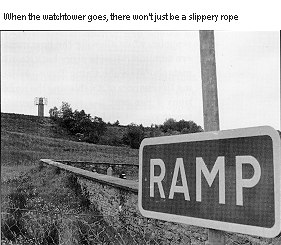

This is in line with the conventional, common-chapters approach of plans north and south in recent years. But, as the earlier argument made clear, the next, and more radical, step is to begin to move towards a single, all-Ireland plan, in line with the development of EU trans-nationalism. It would be the responsibility of the NSMC, in dialogue with the consultative forum, as and when established, to prepare this rolling plan and to monitor, evaluate and review it. Inevitably somewhat thin at first, it would become progressively thicker as the experience of co-ordination developed and it gradually came to supersede separate, partitioned, planning processes. This is a win-win scenario for the two parts of the island. It offers a real sense of economic and social unification to the republic, while allowing the new northern administration to piggy-back (to mix metaphors) on the Celtic Tiger assisting the chances of it achieving the ambitious 4 per cent per year GDP growth target recommended by the SDLP (SDLP, 1999). It can give a strategic focus to the work of the North-South Ministerial Council as a whole, while presenting tangible benefits to both business and socially-oriented constituencies. Amid all the talk of different tracks to north-south co-ordination, it is worth highlighting that whereas in 1922 there were some 20 cross-border rail links, in what was an undifferentiated all-Ireland system, now there is just one (Smyth, 1995: 173). Thankfully, assisted by EU funding, the latter has now been upgraded though it was the subject of a farcical delay at the beginning of the decade when the then Fianna Fail (The Republican Party) transport minister, Seamus Brennan said he was not going to seek to spend large sums on the north-south project "simply for political reasons" (Irish News, May 5th 1990). (Meantime, even more farcically, the Irish Republican Army was blowing up the line.) With the Belfast agreement, such political crassness is hopefully a thing of the past. The goal should be to change all our mental maps in Ireland so that we can pursue this infrastructural revolution in a genuine island-wide way This is very true of transport, given the poor standard of public provision on either side of the border. An early task for policy co-operation between the northern and southern departments responsible should be to commission a feasibility study on a single transport holding company. This would embrace the transport agencies north and south and the goal would be to develop a modern, integrated public transport infrastructure across the island, and beyond to Britain and Europe. Energy, telecommunications and postal systems are also areas where progress needs to be made. In energy, as the ESRI (1999) argues, there is a need for a new gas pipeline and a strengthened electricity transmission system to enhance competition power prices urgently need to be reduced to enhance the competitiveness of northern firms. In postage and telecommunications, the goal should be to ensure that the two jurisdictions operate as inland rather than foreign to one another, through special arrangements between the relevant authorities north and south. Equally, if not more, important however is the soft, human and social, capital we need to accumulate if balanced economic and social progress, widely shared, is to be made across the island. Sustained public-expenditure largesse to Northern Ireland under direct rule may have kept up outward appearances. But it does not conceal the severe underlying failures of the northern polity to date: almost non-existent childcare provision, working-class educational under-achievement, low workforce skill levels, a hard core of very long-term unemployed, poor innovation in small and medium enterprises, and attraction of few globally competitive foreign investors. Many of these problems apply to some extent in the republic as well and often take a similar form. The challenges facing people condemned to live in the sprawling estates of Twinbrook in west Belfast and Tallaght in Dublin are not much different. Where there is clearly a very big difference is in the last factor success in attracting foreign direct investment. This underscores the need for an urgent decision by the UK on membership of economic and monetary union. In Northern Ireland, debate about this issue represents a classic case of economic considerations being overridden by ideological ones and of the disconnection between economic and social constituencies and political parties. Unionist opposition has everything to do with a (misplaced) fear about the UKs, and so Northern Irelands, constitutional future, and shows no recognition of the articulated views of business. The harsh economic realities are that transnational companies will not only tend to seek European investment opportunities within the euro zone but also seek suppliers there too. Staying out of the euro would therefore deprive Northern Ireland not only of FDI opportunities, as against its southern counterpart, but also of potential supply-chain links island-wide. Meantime, Northern Ireland companies would continue to have to pay the severe interest-rate and exchange-rate premia with which UK non-membership is associated a serious matter given so many compete on low-price (and low-wage) rather than high-quality criteria. The aim in this respect should be to remove the border in an economic sense. What is important is to develop the capacity of enterprises anywhere in the island to compete and export globally. An exclusive emphasis on expanding north-south trade an understandable focus of much early discussion of economic co-ordination in Ireland would in that sense be too insular an approach. The risk in such a narrow focus-rather reflected in the brief for the new implementation body on trade and business development as defined in the December 18th agreement between the northern parties (Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister, 1998) would be of reaching a plateau in internal north-south trade and/or merely displacing existing economic activity in the process. This is not to say that north-south trade is inherently finite. The problem, rather, is that (unlike trade between the republic and Britain, or the wider EU), it is currently dominated by traditional, finished consumer goods where markets are limited and displacement effects probable. To move into a higher gear including high-tech, intermediate goods, traded between large firms is dependent on a general restructuring of the northern economy, which remains heavily skewed towards traditional sectors like textiles or food, drink and tobacco. In any case, developing supply chains for domestic suppliers to multinational investors should be given higher prominence. Take the problems (apart from the environmental ones) which arose in Northern Ireland with the influx of British retail food multiples in the wake of the paramilitary ceasefires. Local suppliers were often unable to meet the more exacting quality demands of the supermarket chains, causing considerable tensions between them. Just the same issues apply to suppliers indeed suppliers to some of the same chains in the republic. The answer in such a situation is for a neutral body to broker a network between the key players in this case industry associations, suppliers and potential suppliers, inward investors and any relevant public agencies or expert groups to work out solutions to any problems of quality, innovation and reliability. Hitherto, such tasks have fallen on the IBEC/CBI Joint Business Council. But a public body will always have more clout to play the brokering role. This is a good example of what, concretely, the new implementation body should do. But, again, a note of caution. Once market and co-ordination failures are addressed between two hitherto separate jurisdictions, a range of unintended arrangements competitive as well as co-operative may emerge. So transfrontier integration is not always a win-win game but may mean gains for one side at the expense of the other. For example, because of different duties on petrol and different registration arrangements on the two sides of the Irish border, it is advantageous for northern hauliers to register in the republic. A number of firms have pursued this course, opening up the possibility of a major geographical realignment of the industry in Ireland. Such outcomes are not only very difficult to predict but also, in open economies, to prevent. F reeing up the island-wide labour market is also an important goal. This is especially as the republic faces growing labour shortages though a more welcoming attitude to refugees would help associated with increasing inflationary pressures. These have the potential, at worst, to blow off course renewal of the crucial three-year social partnership agreements via sectional disputes. But achieving free movement of labour across the island means mutual recognition of qualifications and dealing with concerns about national/social insurance records, pension portability and so on.Knock-on changes will be required in the educational domain. For example, common arrangements for entry into post-16 institutions across the island should be developed, allied to a common system of third-level accreditation (Standing Conference, 1998). Some of this will not be easy and will entail difficult trade-offs, including for the republic. Thus, for example, free movement of teachers in Ireland is impossible while there is a requirement of Irish for all who teach in the south (not just teachers of Irish) and while there is a religious education requirement for all who teach in northern Catholic schools (not just teachers of religion). The new Department of Higher and Further Education, Training and Employment will want to give early consideration to these issues, in collaboration with the Department of Education and Science and of Enterprise, Trade and Employment in the republic. We already have close to a free market in goods and services in Ireland, but labour is clearly much less mobile. The question to address is: what needs to be done to establish a genuinely free market in labour?A checklist of matters to be addressed by the NSMC could be readily established by officials from these departments coming together with representatives of the Joint Business Council and the ICTU and reporting. Similar considerations apply to upgrading the quality of labour (and hence the income and quality of life it can command) north and south. A particular focus is needed on those least qualified and most vulnerable to long-term exclusion from the labour market altogether. In that sense the decision to integrate post16 provision in the north in one new department was a bold and sensible one to break down the old academic/vocational divide from which the latter has severely suffered. But there is much to learn in this regard from the experience in the republic, such as in the contribution of the regional technical colleges and institutes of technology to third-level vocational education. The departments, the labour-market agencies north and south, the various educational interests and the social partners should comprise a working party to establish an island-wide strategy for continuous upgrading and expansion of Irelands workforce. As and when the consultative forum is established, its own working groups could make a decisive contribution in this regard. It should be stressed that removing such barriers as different accreditation arrangements is only a necessary, not a sufficient, condition for an all-Ireland labour market to emerge. There is still far more movement of labour from the republic to Britain, for example, than to that other part of the UK known as Northern Ireland just as there is a pattern of Portuguese migration to France. In other words, labour markets need to be socially embedded to work. There is not a tradition of searching out employment or developing careers on the other side of the border. Opportunities must be communicated. There must be a sense of feeling at home in the new environment. There must be an expectation of fulfilment in terms of quality of life. Thus, even in this economic arena, as we shall see below, questions of ownership over north-south integration and of reconciliation between people in the two parts of the island can not be left out of the equation. It is an interactive agenda, at once economic, social and political. A t one level we simply cannot know what the synergies and spillovers will be from more effective co-ordination across the island. The point is simply to address this positive potential, however large, in a non-contentious way.One area where everybody expects significant synergies is tourism. As Paul Tansey points out, "tourism looms less large in the economy of Northern Ireland than in all other economies of the European Union" (Tansey, 1995: 203). Yet the breach in the planned joint tourism marketing campaign by Fianna Fail once returned to government in 1997 in the name of restoring the shamrock to its rightful place (Wilson, 1997) shows that even here ideological questions can intrude. And, because of unionist resistance, the December 18th agreement inelegantly placed what should in effect be a new tourism-marketing implementation body (given it is to be a public company) in the policy co-operation arena. But not only is joint marketing essential. There is also a need to improve the performance of the industry which is being marketed. Tourism facilities in Ireland are by no means always of international standard and joint accreditation of facilities north and south (IBEC/ CBI, 1998), by the Northern Ireland Tourist Board and Bord Fáilte, should be used as a lever to impose more exacting requirements. What, then, of the much larger question of a joint approach towards inward investment? Douglas Hamilton rightly points to the negative synergies of existing arrangements (Hamilton, 1995: 217): "this competition for prospective inward investment projects has led to a bidding-up of offers, the only beneficiaries of which have been the inward investing companies themselves. If policy were co-ordinated, not only could a more effective policy be introduced but budgetary savings would also be realised." There would, of course, be considerable official and political resistance to an integrationist initiative of this degree-and not just from northern unionists. During the negotiations of the north-south structures in the latter part of 1998 evidence of official foot-dragging in Dublin became apparent (Hayes, 1998; Collins, 1998). Coakley (1999) notes the reports of reservations on the part of the of Agriculture and the Industrial Development Authority and adds: "It is extremely unlikely that scepticism or even outright hostility to the strand two bodies is confined to these departments or authorities." But there should be no areas deemed off limits to policy co-ordination. Where there are potential benefits, tangible or otherwise (and not outweighed by attendant costs), these should always trump ideological considerations or bureaucratic inertia. The six implementation bodies and six areas of co-operation identified in the December 1998 statement, in immediate fulfilment of the agreement, should by no means be seen as a ceiling on further integrationist steps. In particular, there are substantial benefits for the north in reconsidering the approach to inward investment. Part of the reason for its more down-market industrial structure is that its grants-based incentives system encourages traditional, labour-intensive, low-profit firms. The system in the republic, by contrast, based on relief on corporation tax, encourages high-technology, high-profit companies to locate there. There is, however, no easy answer to this. Northern Ireland is not fiscally autonomous from the rest of the UK and if it were to be suggested that it be designated an enterprise zone enjoying tax incentives not applying elsewhere there would be very negative reactions in Scotland and Wales, whose inward investment agencies would obviously resist such a move. But there are already some specific tax breaks for firms in Northern Ireland, as the Strategy Review Group (1999) points out (though its suggestion of fiscal flexibility by company would be illegal under EU and World Trade Organisation regulations). What might be explored is whether a fiscally neutral strategy could be developed for the north, linked to a shift from grants to tax relief, within the context of a co-ordinated approach between the Industrial Development Authority and the Industrial Development Board to inward investment. Indeed, a further integrationist step towards an all-Ireland agency for directing inward investment into Ireland as a whole should be seriously investigated. The mutual benefits in reducing competitive bidding for projects, in encouraging a more rational embedding of new firms into supply linkages, and in building upon the (hazy but well-disposed) corporate image of Ireland-could be substantial. But this issue is an example of how north-south integration can not be pursued in isolation from intra-UK or wider EU concerns. As with other questions discussed here, there will be a legitimate British Irish Council role in the debate. U nderlying many of the remaining tensions in this domain is the same problem which bedevilled the establishment of the Executive Committee in the wake of the assembly elections in 1998 trust. The impacted negotiations leading up to the December 18th agreement were symptomatic in that regard of how opportunities can be constricted by mistrustful relationships.Indeed modern economic literature foregrounds the importance of trust (Cooke and Morgan, 1998). Hence Rob Meijers indication that EUREGIO focused for years even decades-on building up the social and cultural dimensions of reconciliation between Dutch and Germans before diversifying into economic development. This is a long-term problem, which is not addressed by short-horizon funding schemes. Fundamentally, this raises the question as to whether the administrations on either side of the Irish border are willing in the long run to pay for the challenge of reconciliation themselves-when there is no longer an EU peace package to do so. Moreover, under the Special Support Programme, we have seen the phenomenon described by Dominic Murray as the new partition of 12 counties from 20 rather than 6 from 26. Yet Cork needs to take part in reconciliation as much as Cavan. As the guidelines for the new round of peace funding are being developed, this absurd geographical restriction must be reconsidered-and, at least, loosened in practice. This is not to detract from the particular needs of those on either side of the border to be able to draw down funds related to social exclusion; but it is to say that those intermediary funding bodies dealing with reconciliation, or indeed business co-operation, need to be able to adopt an all-Ireland approach. It is also remarkable that there is no north-south implementation body for reconciliation itself-even though there is one for languages. It would surely have been preferable if a broader focus on cultural pluralism had been selected-rather than risking, in effect, the importation of Northern Irelands sterile language war, between Irish and the dialect of Ulster-Scots, into the republic. This is particularly so, given the work of the Cultural Diversity Committee (formerly the Cultural Traditions Group) and the Cultures of Ireland Group in this domain, north and south respectively, over many years and the increasing co-operation between the two arts councils. Elaborating new, modernist and pluralist, notions of Irishness - or simply recognising those that are already out there, particularly in the freer cultural atmosphere of the republic-is an exciting and valuable task. Indeed, it is clearly a sub-plot of the Belfast agreement. It finds no place to date, however, in any of the official agenda for north-south relationships as defined by the December 18th statement. Such a broader body, embracing within itself a language element, should have as part of its brief the funding of all-Ireland reconciliatory endeavours. This would provide a 32-county funding stream, assuming the finance was made available, over the long term. In this regard, the decision by the republics government to multiply by a factor of eight its commitment to reconciliation is a welcome start to building up the necessary budget lines, on both sides of the border (Irish Times, April 30th 1999). To establish an implementation body for culture and reconciliation would officially recognise that reconciliation is not just a northern (ie British) problem. And it would make transparently clear that unionists were not being asked to subscribe to a pre-existing, stereotyped, nationalist version of Irishness but to be part of its post-nationalist exploration. Reconciliation, however, is a much wider responsibility, in which schools, for example, clearly have an important role. Yet the Civic, Social and Political Education programme in schools in the republic has no module specifically dealing with northern politics (Irish Times, June 16th 1998) while a separate citizenship education programme is envisaged for UK schools in the wake of the report by the commission chaired by Bernard Crick. The solution to this problem should be to establish a common, north-south element to both such programmes, through collaboration between the two departments of education, north and south, and the curriculum advisory bodies. Schools also need to deepen exchanges between them, especially in the curricular mainstream. The Civic Link project, Co-operation Irelands Project Citizen initiative launched in May supported by the two governments and the US Department of Education-will promote the concept of practical citizenship and involve partner schools from north and south. Experiences gained from this initiative should be assimilated into the curriculum. The churches, meanwhile, need to ensure the training of all clerical personnel includes specific training in the domain of reconciliation. Such training can only go so far if not carried out on an ecumenical basis. As for the media, there is a particular barrier to more shared television viewing. While UTV has more penetration in the republic than RTE in the north, it has acted to block RTE being available on cable to northern consumers, who currently need a special aerial to receive it. This is not, it should be stressed, a unionist defence of Ulster against alien ideologies but a commercial battle for the viewers of Coronation Street. UTvs resistance should be ended forthwith. In the sporting world, the (northern) Irish Football Association and the (southern) Football Association of Ireland should build on the co-operation initiated under their project funded by the EU peace package, A Kick in the Right Direction, and develop much more organic relationships given that even after the second world war there was still intermingling of players between the two sets of Irish green jerseys (Guardian, May 29th 1999). And the Gaelic Athletic Association should not only abolish rule 21 (outlawing Royal Ulster Constabulary members) but also ensure that its government-assisted stadium in Dublin is open to use for other football styles not just American! T his report has set out a much more ambitious agenda of north-south integration-executive, co-ordinating and networking than is usually advanced. Indeed, it sets no frontiers beyond which it cannot go.It does so, however, from a straightforwardly non-ideological standpoint. It is this combination of idealism and pragmatism which can slay, for ever, the Sunningdale syndrome. Bibliography Anderson, J and Goodman, J 1997), North-south integration in Ireland: the rocky road to prosperity and peace, submission to the Forum for Peace and Reconciliation, Dublin Beck, U (1997), The Reinvention of Politics: Rethinking Modernity in the Global Social Order, Cambridge: Polity Press Bew, P and Gillespie G (1993 ): Northern Ireland: A Chronology of the Troubles 1968-1993, Dublin: Gill & Macmillan Bloomfield, K (1994), Stormont in Crisis: A Memoir, Belfast: Blackstaff Press Bradley, J (1994), Troubled by dependency culture, Guardian, January 31st ( 1995), An Island Economy: Exploring Long-Term Economic and Social Consequences of Peace and Reconciliation in the Island of Ireland, report prepared for the Forum for Peace and Reconciliation (second draft), Dublin: Economic and Social Research Institute Coakley, J (1999), The April agreement: redefining the Irish dimension, paper delivered to round-table Redefining Relationships: North-south and East-west Links in Ireland and Britain in the New Millennium, University College Dublin, January Collins, S (1998), North-South agriculture body vetoed, Sunday Tribune, November 29th Cooke, P, and Morgan, K (1998), The Associational Economy: Firms, Regions and Innovation, Oxford: Oxford University Press DArcy, M and Dickson, T (1995), Border Crossings: Developing Ireland's Island Economy, Dublin: Gill & Macmillan Department of the Environment (1998), Draft Regional Strategic Framework for Northern Ireland, Belfast: DOE Fitz Gerald, J, Kearney, I, Morgenroth, E and Smyth, D (1999), National Investment Priori ties for the Period 2000-2006, Dublin: Economic and Social Research Institute Hamilton, D (1995), Inward investment: getting the best from foreign capital, in DArcy, M and Dickson, T Hayes, M (1995), Minority Verdict: Experiences of a Catholic Public Servant, Belfast: Blackstaff Press (1998), Civil service may stymie cross-border ambitions, Irish Independent, November 30th ICTU/CBI Joint Business Council (1998), Position paper on strand two of the Belfast agreement (North-South Ministerial Council), Dublin & Belfast ICTU and IBEC/CBI (1999), The European dimension of north/south co-operation, Belfast and Dublin, April 19th Murray, D (1999), A Register of Cross Border Links in Ireland, Limerick: University of Limerick Northern Ireland Office (1998), The Agreement: Agreement Reached in the Multi-party Negotiations, Belfast: NIO ODonovan, P (1999), Equitably sharing sustainable growth must be our aim, Irish Times, June 2nd Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister (1998), Statement 18 December 1998 Smyth, A (1995), Transport: a hard road ahead, in DArcy, M and Dickson, T Standing Conference for North/South Co-operation in Further and Higher Education (1998), Access to Higher Education in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland Social Democratic and Labour Party (1999), Innovation, investment and social justice: a framework for economic development, Belfast: SDLP Strategy Steering Group (1999), Strategy 2010: Report by the Economic Development Strategy Review Steering Group, Belfast: Department of Economic Development Sweeney, P (1998), The Celtic Tiger: Irelands Economic Miracle Explained, Dublin: Oak Tree Press Tansey, P (1995), Tourism: a product with big potential, in DArcy, M and Dickson, T Teague, P (1997), Political stability through cross-border co-operation, in Bew, P, Patterson, H and Teague, P, Between War and Peace: The Political Future of Northern Ireland, London: Lawrence & Wishart Wilson, R (1997), Political slow learners are reflected clearly in Irelands tale of two logos, Irish Times, November 20th Wrynn, J (1998), Time to give the Celtic Tiger a decent den, Irish Times, November 23rd

John Fee is a Social Democratic and Labour Party member of the Northern Ireland Assembly. (He represented the deputy first minister, Seamus Mallon, at the Monaghan round-table; the first minister, David Trimble, apologised for being unable to attend.) Dominic Murray is professor of peace and co-operation studies, and director of the Centre for Peace and Development Studies, at the University of Limerick. Thomas Christiansen is director of European Studies in the Department of International Politics at the University of Wales Aberystwyth. Moray Gilland is a national expert in DGXVI at the European Commission, on secondment from the Scottish Office. Rob Meijer works at the EUREGIO headquarters on the Dutch-German border. Geoff McEnroe is director of the IBEC/CBI Trade and Business Development Programme. Harriet Kinahan is research and development manager of Co-operation Ireland. Rory ODonnell is Jean Monnet professor of European business at University College Dublin. Hugh Frazer is director of the Combat Poverty Agency Robin Wilson is director of Democratic Dialogue.

Democratic Dialogue {external_link} |