|

Community and Conflict

in Rural Ulster

A SUMMARY REPORT

Dr. Brendan Murtagh

School of Social and Community Sciences

University of Ulster

1996

This Summary Report has been published by

the NI Community Relations Council

6 Murray Street

Belfast BT1 6DN

March 1997

The full research report will be published by

the University of Ulster

Contents

· INTRODUCTION

· POPULATION CHANGE AND COMMUNITY STABILITY

· LIFE IN A SMALL ULSTER TOWN

· LIFE ON THE RURAL INTERFACE

· LIFE AND THE LAND

· IMPLICATIONS OF THE RESEARCH

Introduction

This report summarises a programme of research into community

relations in mid-Armagh. The sorts of social processes that created

fourteen peacelines in Belfast do not stop at the green belt,

and this research aimed to see what effect, if any, they had on

rural communities with a tradition of high conflict. The research

used analysis of secondary data, household surveys and qualitative

interviews to build up a picture of life in the countryside.

Population Change and Community Stability

Since the early 1980s, some peripheral rural areas in Northern

Ireland have experienced population increase and South Armagh

has been no exception. This change has had an important impact

on the communities living in the middle part of the County. The

relaxation of planning controls explains much of, what has been,

a largely Catholic increase in population. As the Catholic population

has increased, the proportion of Protestants living near the border

has steadily declined. In the decade of the 1980s, the proportions

of Catholics living in Keady has increased by one-half a percent

a year whilst in Tandragee in the North of the County, the proportion

of Protestants increased by one- third of a percent a year. There

are also important differences between the population structure

in that, Catholics tend to have a younger age profile, higher

fertility rates, a larger than average family size and therefore

a greater opportunity for self-renewal. The relative increase

in the Catholic population to the South of the County and Protestant

population to the North has therefore had important effects in

the towns, villages and countryside in the middle of Armagh. It

is these consequences that this research is mainly concerned with.

Life in Small Town Ulster

The first part of the research examined the consequences of change,

community attitudes and prospects for the future in a small town

in the area with a survey of 202 households. The names of places

have been changed to allow respondents to speak freely and openly

about their true attitudes and so we refer to the to the study

area as Oldtown.

The town, located near the border with the Irish Republic, is

roughly two thirds Catholic and one-third Protestant. However,

Protestants were more likely to have lived in the village for

a longer period of time and were more likely to describe the village

as Protestant (76%). However, they were conscious that the area

was becoming more Catholic and 61% felt that the town would be

more Catholic in the future. Nearly one-half (47%) of Protestants

however wanted to retain a town mostly of their own religion and

this contrasted to one-quarter (25%) of Catholics who preferred

a Catholic town.

The research also showed that Protestants and Catholic had very

different experiences of the violence and potential agendas for

resolution of the conflict. For example, 29% of Catholics felt

that the town was more violent than other areas of Northern Ireland

compared to 53% of Protestants. Moreover, Protestants felt that

decommissioning paramilitary weapons (82%) was the key to progress

whilst Catholics prioritised more sensitive policing (76%).

Community attitudes in small town Ulster therefore needs to be

understood in the context of the experience of living through

violence, perceptions of ethnic sustainability and the extent

to which demographic change is not detrimental to the link between

community and place. In Oldtown, the recent history of Protestants

is an important backcloth for attitudes and behaviour:

"We saw our friends and relatives killed here and the

people who did it or set them up are still walking around free

... and can 't be touched. It s very hard to talk of community

relations when these people are given protection" Oldtown

resident.

Life on the Rural Interface

The focus of the research narrowed to consider life in two small

villages to the east of the study area.A total of 55 people were

interviewed in Whiteville" a predominately Catholic village

and Glendale", a mainly Protestant village. l)espite the

fact that the villages were one mile apart, there was relatively

little contact between them. Again the different histories of

the two communities have a telling impact on relations, contact

and perceptions of identity between them.

Ten workmen leaving the factory in Glendale where ambushed and

killed in 1976 and shortly afterwards the factory closed, the

local UDR base was destroyed by a massive bomb in 1983, the local

post office and primary school closed last year and the local

Orange Hall was burned in 1995. This catalogue direct and indirect

events has important implications for the local institutions upon

which any community needs to survive and sustain its population

As with Oldville, a high proportion of residents (50%) want to

see the Protestant identity of the village maintained and this

contrasts to Catholics living in Whiteville who were more likely

to have preferred an integrated population profile (62%).

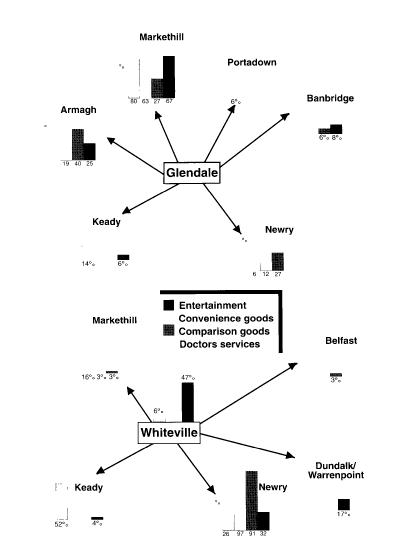

The most enduring impact of community differences on behaviour

is in the way people interact through daily activities such as

shopping and going for services. The diagram below shows where

people from the villages go for shopping for every day (convenience

goods), for larger domestic products (comparison goods), GP services

and entertainment.This shows that people in Catholic Whiteville

travel mainly to Newry, the biggest town in the region, for most

of their shopping and service requirements. Indeed, there is some

evidence that people will travel across the border for entertainment

purposes. This contrasts strongly with the residents of Protestant

Glendale, who look to mainly Protestant towns to the North of

the region such as Markethill, Portadown and Armagh for the same

service.

Life and the Land

The final part of the research looked at life and the open land.

In particular, it emphasised the limited extent of land exchange

between members of the two religions. This is not a unique to

Armagh and studies in County Antrim showed that of the 529 exchanges

of property in Glenravel ward in the 29 years between 1958 and

1987 only 13% happened across the religious divide.1

Our research highlighted the way in which an institutional system

has built up to maintain these patterns. Therefore, there is often

separate auctioneers, solicitors and estate agents dealing with

Protestant and Catholic land exchange thus ensuring that there

is relatively little seepage' between these dual land markets.

This contrasts with the close working relationships between farmers

on a day to day basis. For instance, the tradition of sharing

labour and machinery at peak times of the agricultural year, the

normal exchange of livestock and produce at local 'marts' and

even letting land on long leases or 'conacre' are all well established

practices in the County. However, the transfer of land ownership

is neither widely practiced nor accepted within each religious

grouping.

Implications of the Research

The research has helped to highlight the extent to which religious

dlifferenccs are strongly acted out in rural areas with very different

perceptions of identity and experiences of the violence, territorial

behaviour and ownership of land all signaling the importance of

feelings of belong to particular areas and places.

Many of the problems confronting communities in rural areas result

from relative shifts of population combinedl with the hurt and

fear of violence. Community reconciliation has an important role

to play in identifying and describing the nature of problems in

these localities. In this way, there is a clear link between community

relations and community development as the former can only proceed

effectively if emotional andl practical security and long term

confidence can be secured for that community.

However, it is also about regenerating communities and this respect

government generally and rural development agencies in particular

have a central role to play. Targeting resources and programmes

at areas and issues that will enhance the community opportunities,

for those marginalised in the violence, is a major and often under-looked

task. Decisions taken for rational policy reasons can have disastrous

impacts on communities such as the closure of the primary school

in Glendale. These types of decisions must be taken within the

wider context of efforts to restore community confidence andl

stability in highly vulnerable areas The benefits to rural society,

the resolution of conflict and the quality of peoples lives can

not be undlerstated.2

1 Kirk,T. (1993) The Polarisation of Protestants and

Roman Catholics in Rural Northern Ireland: A Case Study of Glenravel

Ward, Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Queens tiniversity, Belfast.

2 This research was funded by the Central Community

Relations Unit with support from the European Regional Development

Fund. It was also part-funded by the Community Relations Council.

The funders and all those who contributed to the research are

gratefully acknowledged.

© CCRU 1998-1999

site developed by: Martin Melaugh

page last modified:

Back to the top of this page

|

|