Extracts from 'Brits Speak Out',

|

| "The stories of the former soldiers are rivetting, depressing, frightening, horrifying and occasionally transcendent and uplifting. They are fast moving and utterly believable." Anne Cadwallader Ireland on Sunday |

| "Forthright views, many regrets, disturbing memories and littered with

humourous anecdotes" Stephen Gordon Sunday Life |

| "Fascinating reading... Niall Stanage Hot Press |

| FOREWORD |

| INTRODUCTION |

| BERT - ROYAL GREEN JACKETS |

| PETER - ROYAL HIGHLAND FUSILIERS |

| MARTIN - ROYAL GREEN JACKETS |

| JIMMY - ROYAL TANK REGIMENT |

| BOB - QUEEN'S REGIMENT |

| JAMES - ROYAL ARTILLERY |

| PETER - CHESHIRE REGIMENT |

| BOB - LIGHT INFANTRY |

| JOHN - GLOUCESTERSHIRE REGIMENT |

| JOHN - COLDSTREAM GUARDS |

| DEAN - ROYAL ANGLIAN REGIMENT |

| JASON - QUEEN'S LANCASHIRE REGIMENT |

| ANDREW - ROYAL MILITARY POLICE |

| COLIN - ARGYLL AND SUTHERLAND HIGHLANDERS |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY |

| INDEX |

| GLOSSARY/ABBREVIATIONS |

| APPENDIX I - DROPPIN' WELL BAR, BALLYKELLY |

| APPENDIX II- PHOTOGRAPHIC CREDITS |

Thirteen years ago, after spending a term at the University of Ulster at Coleraine, I found myself in lodgings on the Hornby Road in Liverpool. Amongst the other residents were an ex-Para, who for these purposes I shall call Barry, and a former Scots Guardsman, who, for obvious reasons, was known to all the Scousers as 'Jock'.

Barry took great care about his appearance, and we fell out on many occasions on account of my untidiness. Jock had a scar on his chest caused by an injury received on Mount Tumbledown on the Falkland Islands, and another scar on his arm, caused by a needle and indian ink, which read REM 1690. Jock had recently been involved with the riots in Liverpool 8, where he claimed to have helped to protect elderly ladies removing trolleyloads of shopping from stores which were about to be torched.

Both Barry and Jock had served in Northern Ireland. "We should never have stopped folks from rioting in Ulster" remarked Jock "sure the riots in Toxteth were great. If the army ever came to Scotland like we were over in Ireland, I'd give them what for." Barry viewed the Northern Irish situation somewhat differently. Barry's wife came from South Down, and he didn't get on with his in-laws, who now lived in the North of England: "A few well placed bombs left around Dublin would teach those IRA bastards a thing or two" he said.

I was a little bit afraid of Barry. Jock, I considered a mate. Both were accomplished storytellers and their tales of life with the army made many an otherwise dull winter's night pass quickly. Barry told of bizzarre Parachute Regiment training exercises which involved the slaughter, butchering, and burial with full military honours, of a sheep; of finding wounded survivors of terrorist attacks; of blundering accidentally across the border and gathering valuable information from a terrified farmer in the process; of secret observation posts where one night they passed within feet of an IRA active service unit, and on other nights they watched cattle smugglers, or trained their weapons on a man acting suspiciously only to discover that he was hiding in the hedgerow to empty his bowels. Jock told of riots in Armagh which followed the death of hunger striker Bobby Sands, of the unbearable, suffocating heat inside a landrover hit by petrol bombs and of course of the horrors that he had seen in the Falkland Islands.

I left Liverpool in March 1985, and moved to live in Portrush, on the Antrim Coast. Two years later I moved to Derry. In Portrush I had one or two friends who were in the army; the Territorials and the UDR. We looked after each other, but they seldom discussed their work. I would sometimes encounter large groups of off-duty British soldiers in the pubs and clubs of Portrush. They seemed very wound up, and intent on drinking large amounts of alcohol and searching for available women. It seemed prudent to give them a wide berth.

When I moved to Derry, the British Army were extremely visible. Here, they were on duty. Sometimes, after 'incidents', they would appear in large numbers. With depressing regularity the violent demise of soldiers and civilians would be announced on the news. After the death of soldiers I would regard them with both pity, and fear that I might be the target of their revenge. Now and again they would have stones, bottles and abuse hurled at them. Once or twice, when Nationalist anger was aroused, these would be joined by large numbers of petrol bombs, and the following day the city centre would lie in ruins. One day I opened my back door to find soldiers searching my coal bunker. They never raided my home, as they raided many other homes. Occasionally the army stopped me to ask me questions or to search me. Usually they were courteous, although one search was accompanied by a punch in the testicles. Other people in Derry had far, far, worse encounters with these men in green.

The convention in Derry, during 'quiet' times, is to pretend not to notice these armed men on the streets. I observed this convention religiously. Nonetheless, I often thought about Jock and Barry, and wondered how we, the civilian population, appeared to these soldiers whom we so studiously ignored.

The army's presence was the most peculiar feature of this peculiar place that I now call home. Their's are the only guns that I have ever seen on the streets of Derry. Yet these young men, just boys some of them, were also a connection with another island; an island where religious labels are irrelevant and where bereavement to violence is extremely rare.

The wierdest looking people on the streets of Derry come from a place which is normal compared to here. I wondered what they thought. I decided to try to find out.

The British Army have been deployed on active service in Northern Ireland for almost thirty years now. Throughout this time young, mainly English, and mainly working class men have patrolled the streets armed with lethal weapons. What were their thoughts and feelings about the place, and the people they observed? Unlike the locally recruited security forces, the UDR/RIR and RUC they had little connection or personal stake in the conflict here. How well did they understand it? Did they regard themselves as part of a peacekeeping force, or were they combatants in a war? Did they want to be here? Did they believe that they should be here? This book asks these questions of a selection of former and serving soldiers.

Researching the attitudes, opinions and experiences of soldiers who have served in Northern Ireland whilst living and working in a predominantly Nationalist area of Northern Ireland presented a number of difficulties. Practical problems aside, a lot of these difficulties could loosely be placed under the heading of paranoia; both my own and other peoples'. Northern Ireland is (hopefully) coming to the end of a prolonged period of conflict in which over three thousand people have lost their lives. The dead include almost seven hundred members of the British Army and over three hundred and fifty persons killed by the British Army and over seventy 'alleged informers'. In such circumstances I was very anxious that my reasons for wanting to talk to British soldiers should not be misunderstood. I did not want to be perceived to be collecting information of military value to either the British Army or their opponents. Similar fears about my intentions may have affected some of my informants, some of whom seemed torn between a desire to tell their stories and a fear about the uses to which their information might be put.

I was interested in recording the opinions of soldiers from Britain because, unlike the locally recruited UDR/RIR, they are in many ways outsiders to the Northern Irish conflict. This is not to suggest that they are, or indeed could be, impartial observers. Nor is it to diminish the importance of the UDR/RIR; they are representatives of a British presence in Ireland that would persist following any military or political withdrawal by Britain. Their opinions on the conflict in Northern Ireland, however, are by and large already formed when they sign up to join the army.

The British recruited regiments that serve in Northern Ireland represent an interface between the 'mainland' British public and the conflict. They are the sons, occasionally daughters, friends, neighbours and peers of the communities which elect British governments and thus decide British policy. Most British men under the age of fifty who have served in the army will have experienced at least one tour of Northern Ireland. Often they are the only people British residents are likely to meet who have ever visited Northern Ireland. Having come to Northern Ireland to perform a specific role, their perspective is likely to be unusual. It is one that should therefore be regarded with extreme caution. It is one that is likely to be widely disseminated in Britain, but rarely heard in Northern Ireland.

I was anxious to record the opinions of soldiers and ex-soldiers from as wide a range of backgrounds as possible, and who had served here during as many different phases of the 'troubles' as possible. One approach that presented itself was to enlist the co-operation of the Ministry of Defence, and the army press department. This approach was employed by Max Arthur in his book Northern Ireland: Soldiers Talking (London 1987) and has several attractions. The MoD has vast resources at its disposal, it has records of every soldier who has served here, and if it asked soldiers to cooperate with the project, they would have little option but to do so. After talking to other writers on Northern Irish affairs, however, I rejected this approach. Soldiers talking about their experiences at the behest of the MoD would be under enormous pressure to give accounts that coincided with the MoD's vision of what their role should be. Breaches of discipline or procedure would not be reported for fear of repercussions. If the army wish to collect positive testaments to their service here, for recruiting or propaganda purposes, they are well placed to do so. My collusion in such a project would not merely compromise my neutrality, it would be unnecessary.

Recording soldiers' opinions without the army's consent presented new difficulties. One problem was that the army heard about my project and weren't too happy about it. A retired colonel who had, up to that point, been enthusiastic about the project was advised by the Ministry of Defence that: "it would not be in the interests of former or serving soldiers to contact me." I was contacted by one 'former soldier' who turned out to be a crank, much to the alarm of the person whose name and address he used when writing to me. I also received a somewhat unnerving phone call from a Military Police Sergeant (not the Military Police Sergeant whose story is included) making references to a desire to vet me and to have some editorial control of the publication. No threats were made, but it occurred to me there could be worse to come.

Although tens of thousands of soldiers have passed through Northern Ireland, few have settled here, and those that have would be unlikely to want to advertise their presence, given the security situation. In any case the opinions of such soldiers would be influenced by their subsequent knowledge of Northern Ireland. I wanted to find out how Northern Ireland appeared to people who first looked at it from behind British army guns and uniforms. Without MoD co-operation it was impossible to obtain a truly representative sample of former soldiers, with MoD co-operation their testimony would be tarnished.

I wrote to local newspapers in Britain asking soldiers who wished to tell their stories to get in touch. The following letter was sent to some 50 newspapers and magazines:

"I am researching a book about the impressions and experiences of some of the thousands of British soldiers who served in Northern Ireland on tours of duty in the years since 1969. I would be interested in hearing from any of your readers who have served here and would like to share their experiences with a wider audience. Whilst I would be interested in hearing opinions, political or otherwise, I have no interest in any information that could jeopardise anybody's personal security.Some papers published this letter, others probably did not. Ros Rayburn, columnist with the Birmingham Post, turned the letter into a feature on the traumas facing West Midlands soldiers in Ulster. Papers mentioned by contributors when they first contacted me included; The Grimsby Evening Telegraph, The Evening Post (Nottingham), Soldier, Officer and Inside Time (the quarterly newspaper circulated in British prisons). In other cases, I have no way of knowing whether the letter was selected for publication. I also advertised on the internet, through which medium I was told some interesting and amusing anecdotes about army life here. None however led to stories that could be included.I am anxious that this book should not be a work of propaganda either for the army establishment or for any political or paramilitary grouping. Rather, I intend that at a time when there is some reason for optimism about the future of Northern Ireland, this book will contribute in a small way towards building greater understanding between people who have been, willingly or not, involved in the conflict here."

However former soldiers were contacted, those whom I could not

interview in person or by telephone were sent a questionnaire

asking the following questions:

What were your views on the conflict in Northern Ireland before you came to Northern Ireland? How did the army explain the situation here?The stories that follow were put together in a variety of ways. In two cases they are based exclusively on interviews over the telephone. One is based exclusively on the questionnaire. In all other cases the stories are made up from the questionnaire, correspondence either by post or face to face and contributors own writings. Research for this book was carried out between October 1997 and June 1998. During this time a lot has occurred in Northern Ireland. Multi-party talks, which arrived at an agreement on Good Friday, endorsed by referenda on 22 May, took place against a backdrop of uncertainty about Republican and Loyalist ceasefires, occasional riots, a spate of sectarian killings around Christmas and the announcement of an inquiry into the events of Bloody Sunday in January. These events may have coloured the opinions of many of the contributors, so I have endeavoured, in the preamble to each soldier's story, to indicate the time at which it was recorded. Opinions expressed in the pages that follow are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect any of my own views.What preparation/training were you given for your tour(s) of Northern Ireland?*

What was the 'Job description' of your duties here?

What were your first impressions of Northern Ireland?

How did you feel about being posted to Northern Ireland?

What would a normal day's work in Northern Ireland be like?

Were there any duties that you found difficult? Why?

If you served more than one tour of Northern Ireland, were there any differences that you noticed between the tours?*

Did you have any interaction (either on or off duty) with the Nationalist community in Northern Ireland? How do you feel about members of that community?

Did you have any interaction (either on, or off duty) with the Unionist community in Northern Ireland? How do you feel about members of that community?

Did anything that you saw in Northern Ireland shock or surprise you?

What do you think about the Republican and Loyalist paramilitaries in Northern Ireland?

Were there any incidents that occurred while you were in Northern Ireland (riots, shootings, gun battles, contentious parades, funerals etc) that affected you?

Do you think that Northern Ireland changed you/those serving with you? How?

Did you see anything happen/take part in anything that broke the rules of engagement or seemed unfair?

Did any events in Northern Ireland make you take pride in/ give you a sense of purpose about serving here?*

Do you remember where you were/how you felt when you heard about the ceasefires in Northern Ireland?

Do you have any happy memories of Northern Ireland?

How do you feel about the future: for yourself/for Northern Ireland?

Is there anything else you would like to tell me about serving in Northern Ireland?

*Questions not included in early questionnaires.

I make no claim that the soldiers whose stories are included are in any sense typical or representative of those who served in Northern Ireland. In some respects this book is as much about Northern Ireland and ourselves, the civilian population, albeit as viewed from a different perspective, as it is about the British Army. Some of the contributors were contacted for me by other ex-soldiers. Four are serving sentences of life imprisonment in 'mainland' British prisons. One is actively campaigning against the British military presence in Ireland.

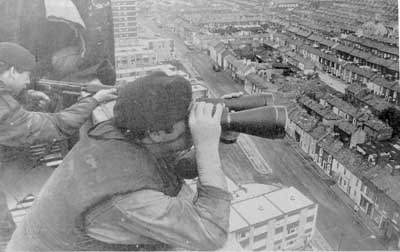

Soldiers in Northern Ireland, in Nationalist areas particularly,

have almost no normal social interaction with members of the communities

in which they find themselves. Drunks, children and mediators

may talk to them, but that's about all. They observe us, sometimes

through the sights of their guns. Always, they are aware that

they are potential targets themselves. Perhaps we may learn something

of the general human condition from the peculiar circumstances

in which the soldiers on our streets find themselves.

November 1998

Peter, a senior non commissioned officer, served five tours of Northern Ireland; Armagh 1969-70, Belfast 1971, 1974 and 1975 and Bessbrook in 1977. Peter was interviewed by telephone in December 1997.

When the troubles first began in Belfast in 1969,1 was on a drill course in Pirbright. The consensus amongst my mates in the army was that: "They'll never send a Scottish regiment". The Highland Fusiliers were recruited from the Glasgow and Ayrshire region and had a religious breakdown of about 60:40 Protestant to Catholic. I don't recall any sectarian tensions within the regiment (although there was some friendly ribbing between supporters of Celtic and Rangers) but it was generally thought that the regiment was too close to the sectarian conflict in Ulster to be posted there.

However before 1969 was out I found myself in a small advance party sent to Gough barracks in Armagh. The accommodation was luxurious by army standards. We were told to regard our role as the 'Midas' touch - Minimum force, Impartiality, Discipline, Alertness and Security. Duties consisted mainly of manning vehicle checkpoints, guarding Northern Ireland's infrastructure, such as water and power installations, and policing the various political and religious rallies that occurred in the Armagh countryside. I didn't take much interest in what was being said at these, although I do remember once hearing the booming tones of the Reverend Ian Paisley preaching from the back of a truck.

We had no real bother on that tour. When we weren't busy with other duties we would help out the locals, mending bridges for farmers, that kind of thing. The only thing that I found in any way shocking on that tour was how drunk some of the drivers were when we stopped them at checkpoints on country roads. You'd open the door and they would practically fall out.

There were no restricted areas for off-duty soldiers then. We took part in Church parades and on Sundays we would go to church, and the Catholic soldiers to chapel, dressed in full uniform. The regiment was split between Armagh, Dungannon and Enniskillen and we used to go regularly to dances in Dungannon. We weren't aware of Protestant and Catholic areas or pubs then and I don't really know if these existed. We all thought that the troubles in Northern Ireland would soon be over, the place seemed that peaceful. The whole tour was a bit like a holiday really.

By the time of my second tour, in late 1970 and early 1971, conditions for British soldiers in Northern Ireland had deteriorated. We stayed at the Flax Mill in the Ardoyne, North Belfast. Conditions were rough there, but not as bad as they had been for the regiment that had been there before us. The changed circumstances were brought tragically home to us in March 1971. Three members of my platoon, Dougald McCaughey, Joseph McCaig and John McCaig were found shot dead in Ligoniel. It is believed that the three off duty soldiers had been invited to a 'party' by some girls that they had met. Joseph and John McCaig were brothers and John was only seventeen; a fact that caused the army to raise the minimum age for service in Northern Ireland to eighteen. I was working in reconnaissance at the time and I know the names of those responsible for the killings.

On this and subsequent tours of Northern Ireland I was sometimes required to give evidence against people arrested by the army and appearing in court. I'm so grateful to Merlyn Rees for releasing one trio that I got put away early; as soon as they got out they managed to blow themselves up.

On another occasion I had to return from a posting in England to give evidence in the Crumlin Road Courthouse. I was met from the Liverpool ferry by a Lance Corporal armed only with a handgun. We had to travel across Belfast and then face the accused in the dock and his relatives in the public gallery.

In the seventies we would be dealing with bombings and shootings every night. You'd have hardly any sleep and the only medical help you were given would be a large whisky in the barracks. Some soldiers were killed with us in Northern Ireland and, well if you're dead you're dead, there's not a lot anybody can do about it. For people who were maimed or wounded though, there wasn't any help given. Two soldiers on my patrol were injured in an ambush one night. One of them was seriously hurt, they had to remove ¼ of an inch from his leg and he was discharged from the army on medical grounds. I met him in Paisley a couple of years ago; he's a forgotten man, he had no help or compensation off the army, so he's left living on the dole. Once you're out of the army the army doesn't care, it's the same for the Falklands veterans and the ones with Gulf War syndrome.

After my second tour of Northern Ireland I came home a different man. I'd have recurring nightmares about things I'd seen in Belfast, in fact I still do. One night my wife told me that if I'd had a pistol under my pillow I would have shot my four year old son. He wandered into the bedroom, as children do, and I panicked not knowing where I was or who had come into the room.

I was in Northern Ireland during the 1975 ceasefire; it was a joke. The IRA was rearming and getting weapons training right through it. They couldn't wait for it to break down and my company commander was killed by a bomb shortly after its collapse. I think the anti-ceasefire groups in the IRA today will get bigger. I mean back in the seventies we had the Official IRA. Look what happened to them.

I don't know how the Provos sprang up since 1969. That was probably a military cock-up. Operation Motorman, when the army entered the former 'No Go' areas, was stopped halfway. If it hadn't been we could have put a stop to things then. The bandits were on the streets, we could have dealt with them. The politicians put a stop to it because too many civilians were getting killed. But if we'd seen it through there would have been fewer casualties in the long run and Adams and McGuinness wouldn't be around today. Sinn Fein has never apologised for killing civilians, let alone soldiers. I've no respect for them.

One time we chased an armed youth into his house, and one of my soldiers saw him hiding a gun in a bedroom. Some local politician (I can't remember his name) intervened and my senior officer agreed that we should only search the house downstairs.

Lots of people on my platoon were commended and decorated for gallantry. We knew we'd done a damn good job there. But at the end of the day the whole thing was a waste of time. All those people killed and mutilated and I just ask myself "Why?"

On my third tour I was stationed aboard HMS Maidstone in Belfast Lough. I met some great Irish people who used to come aboard for work but would then stay for a drink and a chat. Mostly they were RUC men and civilian workers. On the other side, some of the people whose homes we'd have to search would be as nice as pie. Once the curtains were drawn they would chat to you and make you cups of tea. I still come over to Belfast to visit friends there. Mind you I don't tell many people what I used to do for a living.

Peter joined the army in 1973. His first tour of Northern Ireland

(based in Ballymurphy) was in 1974 as he turned eighteen years

old. His next two tours in 1976 and 1978 were based in Creggan.

Peter 's final tour was based in Ballykelly from 1982 to 1984.

In December 1982 he was at a disco in the Droppin' WellBar in

Ballykelly when an INLA bomb exploded, killing seventeen people.

Compiled from questionnaire and correspondence, December 1997

to June 1998.

I joined the army in August 1973, at St George's Barracks in Sutton Coldfield. St George's was your first taste of army life. All trades came there to see films, hear talks and get hair cuts, whether their hair needed cut or not. From there I was sent to Whittington Barracks, between Lichfield and Tamworth in the West Midlands, the training depot for the regiments of the Prince of Wales Division. At the time I was there it was also the site of 'Toy Town', the junior soldiers straight out of school. These poor buggers didn't start their time until they were 18, a long time if they didn't like it.

At that stage everything was geared to getting us through training. We received training in fitness, weapons, map reading, camouflage and concealment, NBC (chemical warfare) and drill. You were 'beasted' to 'build your character'; 18 weeks of blood, sweat, tears and being messed about. You, your kit and your bed would be thrown around or out of the window in their attempt to turn you into a soldier. No day went by without a beasting of one sort or another. This could be a punch or a kicking, press ups or running to the keep and back with your SLR above your head. The days were long; from 0600hrs until midnight and beyond. On New Year's day, after having got pissed out of our tiny minds the night before, we were woken at 0500hrs by shouts and boots in the ribs and made to stand outside in the freezing cold in our PT kit of T-shirts, shorts and plimsolls to be questioned about some food that had gone missing. We were then made to do press-ups and bunny hops until three chaps 'confessed' to taking the food. We didn't get breakfast that day.

The final test came at Sennybridge, near Brecon in Wales, the weather there can be appalling; snow, rain and sunshine all in the same day. On the last day of training we were sent on a 26 mile tab (march) back to camp with full kit; tin toby (helmet), rifle, ammunition, webbing and a large pack. All this was on a near empty stomach as I had not had a proper breakfast, due to another dose of punishment for falling asleep on sentry duty. I was roasting and I remember seeing a water tap, which turned out not to be there when I approached it. It made me more determined to complete the tab, and complete it I did.

On passing out day we showed off to parents and girlfriends with a display of unarmed combat. In the afternoon panic set in as some guys had invited their girlfriends along but found that lady friends from Lichfield and Tamworth had also turned up. A lot of rapid exits were made. In the seventh week of training I was surprised to be given a Cheshire Regiment cap badge. Coming from Robin Hood country I had expected to join the Woofers (Worcester and Sherwood Foresters). It turned out that I'd been requested by the Platoon Sergeant because of my good results at cross country running. The Cheshires are renowned throughout the army as a running battalion and are regular winners of army and divisional cups. It was around this time that people started asking my age, and once I told them that I was 18 they said: "You know where you're going don't you?" or: "Are you looking forward to Ireland?"

I did not really have any views on Ireland before I became a soldier. All I can remember are the civil rights marches on the TV. the burning of houses and the population movement. I joined the regiment on a Tuesday, spent a long weekend at home and on the following Monday at 1800hrs we sailed to Belfast. As for getting the situation explained, nothing was explained until after we were whisked off to Ballykinler [Army Base] to be trained for the streets. We were told that we were there to maintain law and order and to assist the civil powers. The cops were losing their grip, so we were there to support public order so that the Prods didn't batter the shit out of the Catholics, who were shooting squaddies and cops. I'd just come out of training and it didn't register that people, including soldiers, were being injured and killed. In a way I was looking forward to coming to Ireland. It was a chance to prove myself, to try out the skills that I had learnt in training.

My first impressions as I got off the Sir Galahad at 0600hrs were: "What the fuck is this place?" It was damp and miserable. There was loads of noise, shouting troops with black badges and loaded rifles. We were told to get on a four ton lorry which went off through Belfast. My first view of Belfast brought it home to me that I might not come home again. Derelict housing estates, frightened, vulnerable, people who went quiet as we passed. There seemed to be eyes everywhere, and amidst the chaos was the smell of peat fires. "God," I thought, "I'll be glad to see the back of this place."

We had three main work duties; guard duty, patrols and stand-by. Guard duty involved getting up at 0700hrs, washing, shaving, cleaning out our rooms and taking breakfast to go out on duty at about 0900hrs. We would spend about an hour in the observation post before being moved, so that we didn't get too relaxed. Most posts were for a single soldier and you spent the day watching housing estates. Guard duty would last until the following day. In the sangars you would either do the observation duties or read men's magazines and relieve yourself. Some soldiers would fall asleep in the sangars, especially at night. Some soldiers would even defecate in them.

Patrols were also 24 hour duties. We would usually be inspected before going out on patrol (as we were 'on show'). We would get a briefing explaining the task we had to complete. Patrols usually lasted about two hours unless something happened, in which case you would stay out. You covered an area at a time, looking for the local celebrities. You would stop and search a few people and mess them about. Once you'd released people you could get other bricks to stop them. I used to love patrolling at night because the atmosphere on some estates would change; some locals would be friendly, even though during the daytime they would slag you off. You would also be far more alert at nights, you sensed if anything was going off in the estates.

In the 'Murph [Ballymurphy] we 'cross-grained' ie we never went down the streets (because of the shootings). Once, it was decided by high command and intelligence that we were to set a trap for a well known gunman. A company briefing took place in the Henry Taggart Hall (our camp) on the Friday, so everyone knew what to do. On Friday night a full dress rehearsal took place ready for Saturday afternoon. On the Saturday afternoon, we all took up our positions; foot patrols, mobile patrols and the stand-by crews in vehicles. The bait was a patrol of four men, which included the OC commanding A Company, the Intelligence Sergeant, Corporal James from the reconnaissance platoon plus one other. They were to walk down the back of the gardens and draw the fire of the gunman. After ten minutes we heard a single shot go off and the plan went ahead. It turned out that Corporal J had had a negligent discharge (ND) and messed it up. He was fined heavily and banished to an OP on the interface between the 'Murph and Springmartin. The OP was a block of flats overlooking the 'Murph which the army manned 24 hours a day. Basically it was a doddle. We had bedrooms with camp beds, TV, a cooker etc so it wasn't too bad. Prod girls came regularly to meet soldiers. They could strip and assemble our rifles better than us. One Saturday the Commanding Officer made a surprise visit whilst we had four girls there. Boy, you should have seen it in there - chaos. We put them in a flat downstairs and they were never found.

Stand-by was in the main an easy job. There were three kinds of stand-by duty; immediate, ten minute and thirty minute. Immediate stand-by involved eight people, fully kitted out ready to go out to support the patrols. Sometimes we would be called on to escort the RUC, which pissed us all off as they were generally more trouble than they were worth. I used to dread going out with the RUC on the estates; they were always causing hassle with the locals. If we were going to lift somebody it wasn't so bad because it was simple; you went in, came out and then you were away. Ten minute stand-by provided cover for the immediate stand-by, should they be called out. It was more relaxed, you would have to be dressed but you could relax; watch TV, sleep, read, write home, go running or practise zeroing your weapon on the pipe range. You could also get sent out to cover the immediate stand-by. Thirty minute stand-by was like a day off. You could usually stay in bed. No beer was allowed on immediate or ten minute stand-by, but on thirty minute stand-by you were allowed to drink up to two cans.

After any of the stand-by duties, you could be up at 0430hrs for a briefing on the searches for the morning, eat breakfast and go out to give the locals their five o'clock knock. This could vary from a quick search and lift to a search lasting two or three hours or even longer. Two hour searches were normal, usually in the general hope of finding something. Full searches would be conducted by a team trained by sappers, more often than not following a hot tip that we would find weapons or explosives. A lot of the houses we searched were an absolute mess. The first search I went on in Ballymurphy was an eye-opener. I went in the back door, the kitchen floor was covered with water and a bowl served as a sink. A woman came in to rinse a mug out. The water tipped the bowl over but she didn't bat an eyelid, she just went back into the front room.

Some duties were harder, more frightening than others. I never felt safe when using civilian transport for army duties. We would sometimes have to drive down country roads in civvy cars. We would be lightly armed and travelling in twos. The 'boys' could put up a road block and you'd be on them before you realised what was happening. Escorting married people to camp was a routine with set times, so the PIRA or INLA could easily have set something up along the route; you were stuck inside a bus which everybody knew was military. Similarly when we would take foot patrols out in civvy vans, all the world would know that it was military. We were fully tooled up and we had a drill in case of attack, but, encased in a van, we knew we wouldn't have had a chance.

Amongst the unusual things that occurred on patrol was an incident in the Beechwood area of Derry. We were being hassled by a young drunk when my Lance Corporal saw a chap who was in one of the 'organisations'. The Lance Corporal asked this chap whether he could get the drunk to go, and to tell him that he would be lifted if he didn't. The guy went over and told the drunk in no uncertain terms to go home. The drunk refused and began to get even more abusive. The other guy then smacked him around a bit. We were then allowed to get on to our transport, minus one drunk.

Following up tip offs could also be scary. We would get information to go and look, or search or watch somewhere. It could be a set-up, so you'd get twitchy. It was worse if someone told you something while you were out on patrol and you had to go to investigate it. In the Creggan one morning we were in a woman's garden and she had spoken to us. Later in the day we were sent to look for her two kids - to no avail. The next day the Engineers recovered their weighted down bodies from the reservoir near Rosemount. The woman had lost her husband courtesy of the IRA.

I always say that you go to Ireland a boy but within days you become a man. It's serious, as people want to see you dead and will go to any length to achieve this. I was happy-go-lucky before I went to Ireland but I came home getting worse and worse. I became violent and developed a drink problem. My mum told me I came home one night running down the street kicking hedges and shouting: "Sniper! Sniper!".

I have mixed feelings about what the army achieved in Northern Ireland. I believe that we did do a lot of good in stopping the idiots on both sides from carrying out acts of violence but we also started a lot of trouble, mainly due to boredom. We got a unit of PIRA disbanded in Ballymurphy in 1974. This was through internment without trial. It proved that we got the right people but just like fishermen at sea sometimes you get the wrong ones. The RUC have done a lot of this kind of thing and one day will have to answer charges in court - it's going to cost a lot of money. When searching business premises the military/ RUC would take items away. In Kelly's bar in Ballymurphy beer was put in the back of a landrover and it ended up in the RUC 's place. That was theft.

When we lifted people they were seen by an army doctor in camp. Many a day or night I would listen to them being smacked around, sometimes quite badly. The doctor would do nothing on his visit after interrogation. I also believe people were fitted up for incidents, I don't care what people say, I won't change my mind until I die. The Droppin' Well bomb springs to mind. When I was in hospital, detectives took statements about it and within 24 hours two women had been arrested and charged. I think that they got seven years each. Why weren't we asked to give evidence or identify them? After all we would recognise them if they had been in there, wouldn't we? We never got the call to go to court. Why? I mean it's only two bastard Catholics isn't it? No it bloody well isn't It's two people who lost their freedom for something that they perhaps never did.

Bloody Sunday was murder. The Paras lost it and there's been one massive cover-up. I know people who go into discos and beat up spastics; these people are Paras. The people of the Bogside and Derry should not give up. When justice comes for the Paras it'll be like the Clegg case I suppose.

When I was in the army I worked mainly in Catholic areas and I detested most of the people. If we thought people were 'involved' we would chase them and mess them about. In the daytime we had to put up with all sorts of crap, but at night you would very occasionally meet some who were quite friendly. Our commanding officers demanded that we should be 'firm but fair'. It didn't happen all the time, but generally I think that we had the respect of the community, especially in Derry. We only suffered a few attacks, and this we put down to our approach to the community in general. In Creggan we tried having kids in our camp for a while, so that they could see that we were human. They would play football, get rides in pigs and choppers. The kids had loads of fun but I believe that the PIRA told people to stop sending their kids up to us. One lad, Billy, got his head shaved as a punishment for his friendly approach to troops.

Today I feel sorry for the Catholic community, although not for the terrorists. They have to put up with the RUC, the army, the Prods and their own organisations ruling their lives. It's time people let them be in control of their own lives; they deserve it after all this time. I feel strongly about them, it's as though I should repay them somehow for being a bastard whilst I was over there. I'd like to help them get back on their feet, rebuild trust in their community. I'm not brainwashed now. Despite all that the PIRA and INLA did to me out there (and it's a lot) I'd like to speak out for the Catholic community. Having lived amongst them, I feel I have had a privileged insight into their lives. They are not all anti-British or PIRA supporters, many just wish for a peaceful life. Many people in Britain are used to seeing dramatic headlines about Northern Ireland, but I knew it was 99% peaceful and 1% trouble.

I feel hatred for the 'sticky bun' [Protestant] community. Our company was once tasked to watch over a bridge near the Mary Peters' Track in Belfast so that the Prods could march over. On the day they came across one guy called us every name under the sun. We had only guarded the bridge all night so that the IRA didn't blow it, and them, sky high. These bastards caused it all in my eyes. They took all the best jobs and housing and provoked the Catholics into action. They seduced the army with sex, drink and sticky buns. They are a disgrace. As for Paisley, I put him on a par with Hitler, Stalin, Idi Amin and Saddam Hussein. I honestly would love to see him and [Peter] Robinson [deputy leader of the DUP] out of the way, dead. It's terrible that I feel this way. If the Prods hadn't been greedy I wouldn't have had to get involved, I wouldn't have lost my mates, I would not have had to go to a shrink and a therapist to make me human, I wouldn't have suffered pain and illness and I wouldn't be angry. I'd love to be normal and not react to cracks, bangs and people making me jump. I spent a lot of time walking backwards on the streets and now I can't stand people coming up behind me; if they do they're fair game. I call my hands 'bastards' because I hit people without warning.

If you look at the IRA in a professional sense, then you have to admit that they are exceptional. I see them like the resistance against the Germans in the Second World War. If they were in the British Army they would be in the special services. Some of the paramilitaries in PIRA and other organisations are real psychos though. The people of Ireland deserve better than these bastards. What right do they have to say what you should do, who you should marry, where you can live. Why should people have to live by their rules? Why should they kill, beat or kneecap people who don't follow them? It will take brave people to get rid of them, but I know one day it will happen and I hope I'm alive to see it. Both communities know these bastards and eventually they will stand up to them and make them know they will not tolerate them. They are pathetic; they are not protectors of their communities. They are bullies and parasites. They think that they have authority and respect but they are elitists. I think that they are insecure, sheepish, silly and could be pitied for feeling the need to kill, maim and torture innocent people. In later life they will regret it, just as I regret things I did whilst in the army. Once the situation sorts itself out, I wonder whether they too will need help to adjust to the ways of a normal society.

We were allowed a week off on leave to England occasionally. A flight was paid for at Aldergrove. In England you would get pissed and, if you were lucky, have sex. For rest and recuperation in Ireland we could go to Bangor or Coleraine to relax and get pissed.

Monday 6 December 1982 was to be a day that changed my life forever. It had started like any other Monday morning; we got up at 0600hrs and washed, shaved and got ready to go to work, cleaning the blocks out after spending the weekend on the piss. At 0700hrs it was breakfast of sausage, bacon and an egg, all washed down with a mug of lovely army style tea, before going back to the block to get ready for company muster parade.

At around 0730hrs the 'bean stealers' or 'pads' [married soldiers] would come in and it would be, "borrow me this, that or the other". It really pissed the single guys off, because they would sit on your just made bed and undo what you'd just tidied up. What can you say to corporals or lance corporals? Not a lot.

By 0745hrs we were formed up by platoons on the square for muster; the army's way of finding out who was where, and an inspection of you and your turnout. It was also, without fail, a time when individuals would be charged with various offences and asked why they were dirty, grotty, minging or leaping, as the army defined states of dirtiness. Most would get a 242 (charge sheet) against them for dirty kit; jacket, denims, boots and regimental buckle. If you weren't presentable you would get it, or you might have to go on staff parade in the guardroom at 2200hrs to show that you had rectified your fault. Some, especially those who didn't 'fit in' with the rest, would be whisked off to the parade ground to jail.

After muster, depending on the Company Training Programme, there was running, weapon training, infantry skills, camouflage and concealment, shooting on the ranges, or just sitting writing letters, watching TV or sleeping. This would go on until NAAFI break, when we would go for a brew and pie before starting again, or not, as the case maybe.

At l230hrs we would stop for dinner, organised chaos more like. Try to imagine 200 plus squaddies lining up to fill their stomachs, larking around and a lance jack letting in ten at a time. The 'bean stealers' would creep around the single blokes in an attempt to get some connor (food). Once inside, it was like any small restaurant without waiter service. Very often you would come back and find a pad dossing on your pit (bed), complete with boots on. They had no respect for our bedspace or privacy.

We generally had sport; football, running or squash, in the afternoon unless military activity was required. It was a time when the Battalion would run sports competitions of some sort. This would go on until 1630-1645hrs when you would check the Company or Battalion part one orders, to see if anything, such as medicals, duties or promotions, affected you, before going for tea and the pads going home. The only difference that day was the NCO's cadre had been completed and the once privates were now on the first rung of success, lance corporals/lance jacks.

It hadn't been a particularly warm day and so a chance to keep warm was greatly appreciated. Tea was much like dinner, a proper dinner; beef, pork and the trimmings. There was washing, ironing, writing, showering and watching TV. At 1900hrs David 'Gump' Stitt, Phil 'McDuff' McDonagh, Steve 'Baggy' Bagshawe and myself were upstairs in the NAAFI's Corporals Bar having a beer and playing pool. It was just us and the barmaid. I don't know how long we had been in there when Corporal D came in pissed, shouting and swearing. We had put up with listening to him for months and were fed up with him. I said to my mates: "Hows about going to the 'Drop' out of this bastard's way?". They agreed. The 'Drop' had only just come back 'in bounds' and the chance to get out and maybe meet some women was uppermost in our minds. It has been a decision I've regretted ever since.

We got there and went down a corridor type entrance to the disco. A young lad was on the door and in we went. There were quite a few people in, some were celebrating their promotions, so there were more people in than normal, especially couples from the pads.

The pub was soon packed with squaddies and local girls, all intent on having a good time. How long I'd been in for I don't know, but I was sat against the back wall, where Shaw was sat and he asked me to swap places so he could be next to his girlfriend (see diagram, appendix I). It was coming up to 2300hrs and Mirror Man was playing, a few people were dancing. I looked up at the clock and, as it was nearly on the hour I downed my pint and motioned to Stitty to sup up before the bell. As the pint pot touched the table I saw what I thought was a camera flash, very quickly followed by a loud crack like a plastic ruler being slapped on a desk. Then I was hit, I can only describe it as like being punched by Frank Bruno. I went to sleep. I never left any beer.

When I woke up I could hear quiet moaning and a small fire, but I couldn't see as my specs were gone. I felt no pain, there were no bodies visible, just complete darkness. It only took a short time for it to register that I'd been blown up and must escape. I went on autopilot. I knew where the exit was and made my way to it. My only thought was:

"Get out. Get out". I knew that a favourite tactic of the IRA was to plant a secondary device to catch out the security forces. I'm ashamed to admit it, but I never gave my mates a thought. Self-survival took over.

Whether the door was there, I don't know, but my first sight was the step up to the road and people standing there looking at me. There was no sound, just silence, still no pain. I got up to the road. My second thought was: "Get to camp pal, you're hurt". I remember approaching the other bar on the opposite side. I was bent double, walking slowly to camp, when two squaddies got hold of me and helped me into camp. I can't remember walking to camp after that. It wasn't until I got to the guardroom that I became aware of the pain in my back and I remember telling the two soldiers to: "Take it steady." I was bent double, gasping for breath and still I couldn't hear anything. I got to the medical centre (MRS) and sat down. A medic asked me my name, number and rank and where the pain was. I was transferred to a bed of the type doctors have in surgeries.

It was then that I really noticed the chaos going on, with squaddies coming in and medics and medically trained soldiers picking them up. There was still no noise. At this stage I started asking: "Where's my mate Stitty? Where is he?" and was told not to wony, he was okay.

Shortly after, I was told I was off to hospital and that a chopper was soon coming. I told them that I was afraid of flying. A staff sergeant told me to: "Fucking shut up. You're going". So off I went, walking to a chopper, and was told to lie down. I know that others were with me but all that I remember is the squaddie who had been the first to get to me on the road. That was comforting.

On arrival at Musgrave Park I was put in a wheelchair and I went to a waiting room. Again I was with others because I remember a medic cutting a guy's trousers and thinking:

"He ain't doing that to me. I've only got these." He didn't. I was x-rayed and put in a bed. I never knew what I had done until a male nurse, a Jock, said: "Look mate, are you going to lie down flat, or do you want to be a spastic for the rest of your life?" I lay flat.

One morning the doctor had been round and a nurse said: "Take this, and ring if you need a bed pan." Nothing. In the afternoon I was told to swallow some yellowish liquid, and to ring if I wanted a pan. Nothing. And so it came to pass that a wife/girlfriend of a UDR soldier came to visit bearing gifts, well, a couple of cans of Harp lager actually. A can was passed around and I had a slurp. Within minutes I was pressing and pressing and praying. I requested a pan - nothing. I put plan B into operation; I got up to go to the toilet. I was told by a mate to be careful, otherwise I'd collapse. No way. I wanted to go and I was going to go come what may. I went in, and I was doing what you have to do, when the nurses came banging on the door asking if I was alright. "Alright?" I was in heaven. So, all you people who knock Harp lager, it does reach to other parts and it works.

I remember various incidents which occurred whilst I was in MPH. It was close to Christmas and the decorations were up, although the Jock nurse kept cutting them down. A soldier, Private T, kept running around as if it was his birthday. He was always up at the female ward, not bad for an injured guy, was it? When the TV cameras came in he put on an act about what had happened in Ballykelly that any professional actor would have been proud of. It turned out that he had been in camp when the explosion occurred, the lying bastard. He was pissed and had headbutted a door. That was why he'd been sent to MPH. I later found out that my mates had smashed up his TV and stereo for obvious reasons. Sergeant Evans, his platoon sergeant, threatened him with serious grief if he put in a compensation claim. He never did. On another occasion a Catholic priest came in and asked me for forgiveness. He hadn't planted the bomb. Why should he apologise? He'd had a drop or two but he was brave to enter the lion's den.

They were going to send me home for Christmas. All of a sudden, I was told that this was to be delayed because a VIP was going to visit. On the day there was chaos and panic and about an hour before this person was due, we were told that it was Maggie Thatcher. I remember thinking: "Whoopie shit, I've lost a day for you." At about l000hrs we were lined up and in she came. She stopped at me, and said: "Hello, and where in Cheshire do you come from?" "I don't Ma'am" I replied "I'm from Nottinghamshire" "Oh, I'm from Grantham do you know?" She asked. I answered: "Yes ma'am." Then she was gone. Was that it? Was I supposed to be better for it? Was I fuck. I'd lost a day for that cow. We all know now that all she cared about was herself and her image. After suffering something similar I wonder if she is now more compassionate towards victims of violence. I very much doubt it, she seemed an insensitive bitch. Brighton, I hope, made her realise how vulnerable we are to acts of terrorism, and that no amount of security and money can stop a determined terrorist from achieving their ultimate goal.

I was known throughout the Battalion as 'Peter Porn', due to my interest in filth, porno and men's mags. I was visited by two ladies from the NAAFI and, in conversation, I told them that I hadn't had an erection since the explosion. So what did they do? No, not that, but they brought in several copies of Escort and Fiesta to see what that did for me. It worked a treat.

We had a visit from Jim Prior and his wife. This pair were completely the opposite of Maggie. They were caring, sensitive and took time to listen to me. I'd like to say to him: "Thanks mate. You and your wife were a lovely tonic."

When I came back I couldn't do any soldiering, but it didn't stop them from sending me to Aughnacloy. I never said goodbye to my mates. No-one cared to ask me if I'd like to go to their funerals. My mate is in the goalmouth at Man City, the Kippack end, I believe. I always knew that he was a crap goalie. We had a memorial stone erected in Ballykelly and the families of the dead were invited to attend. Afterwards we mingled with them over a drink. My Company Sergeant Major said he was going to bring over Shaw Williamson's parents and girlfriend to talk to me. "No sir, I can't." I told him. I was told to talk to them anyway. It was extremely difficult to talk about Willie, knowing what I knew up to the time of his death.

As a civilian I was told about our special area in Chester Cathedral. My mate wanted to take me there. I put him off. I wasn't ready. Two years later I went on my own to see it. It gutted me, but I did it. Now it's sad when I go there before the regimental day out at the races. But I go there. I must for them.

I was 'lucky' to survive the Ballykelly pub bomb. I lost five good friends. I suffer from post traumatic stress and all that that involves. I'm off tablets but I still have problems. My temper is a big problem as I can snap at the simplest things. I'm working on it and I try to escape. I have panic attacks and I cannot stand being trapped in rooms full of people. I can't go to a disco without the fear of being blown up. When I go to pubs I always sit with my back to the wall, so that I can see everything in front of me.

I sometimes knew when something had happened or was about to go off by a cold feeling I would get. I knew I would be blown up and survive. I knew there would be a bomb attack in Leeds but I got the date/ month wrong. I find the 6th of December a bad day. Most years I have bad memories, but sometimes I just break down.

I've not had any help from the army in dealing with these problems. It was only after I left the army that I got the help that I needed; a shrink and a therapist. I thought I was going crazy and would end up in hospital. I wanted to die to stop it all. I had the 'why me?' syndrome: "Why did I come out alive?"

I believe that I had some sort of breakdown in the army. I attacked a corporal with a glass just because he shouted at me. I was sent to military jail for the attack, and rightly so, but afterwards I was put back on my job. One night we were having our Christmas party in Ballykelly, a year after the bomb. I was told to escort the pads to the venue in the camp. As I came to the gates I just cried my eyes out and eventually went into the function. I had to keep going out because I felt so bad at one stage that I remember having this 9mm pistol which I used for escort duty and, because of the rage within me, I wanted to cock it and blast it off into a small stream. I then went crying to my Sergeant Major and gave him the weapon; I felt too unstable to have it.

One chap that I knew shot himself in the upper arm in an observation post. He'd been messing about, probably through boredom. He was sentenced to 14 days in the guardroom at Creggan Camp. This was nothing like the Battalion 'nick', just a room, and we gave him fags and sweets. He never got beasted like in the normal nick, no show parades, it was dead soft. When he went to civvy street he got into his car one day and, at full speed, smashed into a brick wall - dead. Had Ireland claimed another victim?

Another guy who was injured in the pub bomb will not go out and mix with society. It's called public avoidance and to a certain extent I have it too. Today I'm getting better. Recovery will take a long time but I am determined to get there.

When the ceasefires were announced in Northern Ireland, I was at home in Nottinghamshire. I was so chuffed and happy. I was hoping it would work, for all the people to see how life could be if you stop the ball rolling. No more deaths, no more tears and suffering. They could come out of the darkness to play in the sunshine.

Mo Mowlam seems to be going about Northern Ireland the right way. She isn't out for personal rewards like Major and Thatcher were. I hope she can succeed where others have failed. The road is long and full of holes which can be fallen into. Only the wise will come through, to see it's better at this end. Northern Ireland is a lovely scenic place and so are some of its people. I just hope that you can all realise your dreams.

For myself I hope to get back in order mentally, to be able to travel freely without panic attacks. I want to help disadvantaged people, regardless of race or orientation. I work for the Samaritans which is my way of giving instead of receiving. I'd like to go back to Ireland, especially to Creggan, where I feel sorry for the people who had to put up with me and other arseholes wrecking their homes, lives and faces. I'd like to do something to help them to repair their lives. To any Derry Catholics reading - I'm sorry for having been so ignorant to you all and unleashing my frustration upon you all. Someday it's going to be different.

Roof-top OP, Belfast

Colin, a private, was based in North Howard Street Mill in West Belfast from May to November 1994. During Colin's tour both the IRA and the Combined Loyalist Military Command declared ceasefires. As a result his experiences were very different to those of soldiers in West Belfast in earlier more troubled times. Compiled from questionnaire and correspondence March to April 1998.

Both my mum and dad are Protestants and were members of the Bridgeton Flute Band in Glasgow. It was only natural that I was brought up the same way. I live in Clydebank which is on the outskirts of Glasgow and the town is said to be about 60% Catholic. The schools are mostly split in Scotland for the Catholics and Protestants but I don't really know if it was intended to be that way. I went to mostly Protestant primary and high schools and we used to always have fights after school with the Catholic schools. At the time I never really knew what the difference was and it was just a case of our parents calling them the 'dirty fenians'; we were always told never to play with them in our street or we'd catch a disease from them. As I got a wee bit older my big brother used to take me along to the big Orange walks in Glasgow during the marching season and I thought that was great. He then joined an Orange accordion band and used to take me along to band practice during the week where I then started mixing with the adults and found myself forming the same views as them. Before long I joined a band myself and learned to play the flute in the Clydebank Loyalist Flute Band when I was about 14. I took part in some of the big walks in Glasgow but lost touch with the band when I joined the army. Most of my mates when I was younger were all from the Protestant school so I was always mixing with my own kind as it were. Football plays a big part in the bigotry in Scotland with Rangers and Celtic. It almost always caused fights at the weekends when one team lost or what not and when both teams played each other it was mayhem. As I grew older I really formed a hatred for anything Catholic and anything to do with Celtic, although now I don't mind the Catholic people so much, but I still hold my strong views on Celtic. In my younger days I never really knew much about the situation in Northern Ireland because we, as kids, were fighting our own little wars but, as I got older, I became more aware. I had always secretly agreed with the methods used by the UVF and UFF; I thought the Loyalist groups were doing a great job by getting rid of the blokes who were killing kids and innocent people and putting bombs everywhere. It was also the way I was brought up with the old scenario: "Good guys and bad guys".

Having now served in Ireland I can understand both sides and my views changed pretty dramatically. The army explained the situation as being fragile and that both sides were as bad as each other when it came down to terrorism, but that there are also many decent folk living there.

When I first was told about the posting (the CO broke the news in the gym at Shorncliffe Camp) I felt excited. Although there were some dull looking faces, most guys were fairly happy, especially the guys who were going for the first time; it was a chance to earn a medal at long last.

We had a fairly large chunk of training for the province which included using shooting ranges at Lydd and Hythe in Kent and lots of in-camp training from the guys who had done previous tours. My first impressions of Northern Ireland were that Belfast was just like any ordinary city. When you're doing your training you build up a picture of a place where terrorists are lurking in every doorway and window and it's nothing like that. The fear of the place seemed to dwindle fairly quickly and it was down to the job of keeping the peace.

We were in Belfast to assist the RUC to carry out their duties of enforcing the law and to maintain public order during riots. A normal day's work involved around five or six patrols of one to two hours, assisting the RUC or forming part of a cordon team during house searches. The work became boring and tedious at times, and very often tiring. The sangars we used in North Howard Street Mill were basic to say the least. We spent two hours in each sangar, with about four sangars to rotate around, so things could become pretty boring at times. There was never any heating in the sangars which was a nightmare in winter and, in summer there was no air conditioning, which was also a nightmare. It wasn't as though we could open the windows. Every time we took a sangar over from another soldier we were supposed to check the equipment but it was more like a treasure hunt, looking for the porn mag, hidden so that the officers didn't find it. Basically sangar bashing was the worst job on my whole tour.

During my six months in the province in 1994 we carried out loads of house searches. There were too many to remember exact numbers so that gives you a rough idea how often we did them. Most of the time these searches were carried out at around five or six in the morning so there weren't many people around to cause trouble. The searches took anything from two to four hours so they were over with fairly quickly. I never actually carried out the searches myself but I was on a fair number of cordons. It always pissed me off being on cordons. I felt unsafe standing about in one place for too long, but the job had to be done. We did find stuff on a few occasions, one day we found a coffee jar bomb, primed and ready to go, and we were pretty chuffed because it could have been used on our troops. Doing house searches is not a nice or enjoyable thing to do, but it has to be done. I know if I was one of the people whose house was getting searched I'd be pretty pissed off. I think people over there who want peace have to realise that the army has to carry out these searches in order to combat terrorism.

Whilst doing a search of a derelict house in the Shankill, my team were told to go onto the Shankill road. As I stood in a doorway, a bloke in his 40's said to me: "You won't find nothing in that house down there." I replied: "I don't really care mate." When he heard my Scottish accent he asked if I was a Rangers man, when I said yes his whole attitude changed and all his mates started shaking my hand. What I'm trying to say is that I found the Protestant community very friendly towards us which eased the pressure in those areas.

Most of the tours were done in the Catholic areas such as the Falls, Beechmount, Clonard, St James etc so we only went into the Shankill now and again. When we did go into the Shankill after the ceasefire the Protestant community seemed pretty pleased to see us. They were a bit unsure of the reasons the IRA called the ceasefire, which was only to be expected. I enjoyed doing my patrols in the Shankill because it was a welcome treat after the abuse and tension of our usual areas of patrol. I spoke with a number of Protestants and it was great just to be able to talk to some of the people over there and get an idea of the different side of the peaceline. There was the odd person in the Shankill who made the comment that we ought to be on the other side keeping an eye on them. My impression of the Shankill was that it was like a totally different place compared with that of the hostile community on the other side. I found it quite a pleasant area to work in.

Most of these people are just going about their daily lives and I even found the terrorists we knew to be very pleasant. The main problem I found in these areas were the drunks and young kids who are just looking for an excuse, through boredom, to attack soldiers. Verbal abuse was an everyday occurrence over in Northern Ireland and we had to take it with a pinch of salt. We used to give as good as we got and the young guys used to give up after a while. The physical attacks were a wee bit different though. On three occasions over there I had a knife pulled out on me. The first time was outside a chippie on the Falls (The Blue Star) when there were a group of approximately 15 youths, all drunk on a Friday night. One of them came up to me and squared up before pulling a knife on me. My team commander came running straight over to me and moved me out of the way, but the young boy kept following me waving the knife about. My team commander then cocked his rifle and pointed it at the guy. His mates came running over and dragged him away saying: "C'mon Joe, I think that gun will do more damage to you than that knife will do to them." That was the end of that situation. A lot of the time we had to suffer bricks and bottles flying at us from all angles when we were on top cover. We were trained well enough for this kind of thing before we came over to Northern Ireland so we were able to handle things well enough.

There was another incident where a car bomb which was planted by the Loyalists outside the Sinn Fein office at the junction of the Falls Road and Sevastapol Street. Our troops were about 100-200 metres away when it went off and our immediate action was to seal off the area. As we did so we were surrounded by about 100 youngsters, 14-20-year-olds. They started to scream abuse at us and throw punches, accusing us of turning a blind eye to the bomb which was untrue. We let off a few baton rounds until more troops got onto the ground. That was probably about the most frightening thing that happened to me over there. I could go on and on about more incidents of abuse etc, but I'd be here all day, because these things were just part of everyday life to us over there.

The state of some of the areas shocked me. For a place with strong community bonds they seem to let their areas fall into decline. These people have to live there, whether they like it or not, and you'd think they'd take care of where they live. Both sides have an argument for what they are fighting for but I have to say I'm more in favour of the Loyalists. Perhaps it was the way I was brought up or a combination of that and the fact that, while serving in Northern Ireland, I never had any bad run ins with the Loyalists. They both go over the top with the violence. The situation changed my way of thinking slightly after seeing some of the people affected. I now don't take sides as much and I'm more aware of what is going on in Northern Ireland. I can't comment on others.

My team commander went out drunk on patrol one night and started to abuse two couples as soon as we left the base. I went over to try and calm the situation down but my team commander pushed me out the way and proceeded to strike one of the blokes on the jaw with the butt of his rifle. To me this was totally unjust and out of order and a potentially dangerous situation to get into, as the couples had just left a busy pub. Fortunately it never went any further and we got away with it. My team commander then gave the boss some grief half an hour later and got caught being pissed. He was shipped back to the UK the following day.

The feeling in and around the Catholic areas of West Belfast leading up to the 1994 ceasefire was that some sort of major victory was about to happen for the Provos. I couldn't understand why the Catholics were so excited because in my eyes it looked like the Provos were backing down by calling a ceasefire. Once the ceasefire was called, all the Catholics seemed to pour out onto the streets with tri-colours and banners waving every-where. I really just couldn't understand what there was to celebrate about, death and destruction perhaps.

There were a few 'Time to Go' marches which we had to police but most of the time we kept a fairly low profile so as not to entice any trouble. We got all the usual old taunts, which a deaf ear had to be turned to, and quite often we gave as good as we got (verbally). I don't know what it is about Belfast, but we, as a Scottish regiment, never seemed to get as much hassle as the English ones. I think the Scots are more on the Irish wave length and can handle the situation over there with a bit more humour. Anyway, the Catholic community were giving us loads of grief about how we shouldn't be there and that the ceasefire was in place so it was time to go. My own feelings were that it would be wrong to pull out straight away because the ceasefire had only just been called. I also thought that to pull out would be giving the IRA etc a chance to move around without the hassle of having troops around. August 1994 was a critical time, both for residents of Belfast and for us soldiers. We had to handle the situation very carefully, which I feel we did very well. I suppose the people in the Catholic communities felt their demos were justified, but things like that don't just happen overnight.

One happy memory which will always stick with me is when, shortly before the ceasefire, I was on patrol in the Devonshires area of West Belfast. We stopped in a street for a few seconds when a young lad came over to speak to me. He was only about three years old. As I was talking to him, I saw his mum coming out the house, shouting at him not to bother the soldier. She came straight up to us, and I was expecting a torrent of abuse, but instead she stood there and spoke to me like a human being and not a uniform. It was the first time anyone had spoken to me with any respect and I'd been there for three months.

Northern Ireland was, without a doubt, the best and most enjoyable part of my army life and whenever someone mentions the army to me, the first vision I get is of Northern Ireland. When I see the province on the TV, I sometimes wish I was still there. I am proud of what I achieved there and no-one can ever take that away from me. The 1994 ceasefire will be with me for the rest of my life. It was great to see the delight in peoples' faces at the prospect of no more killings. It was great for my family to know that their son/brother was part of it all. Northern Ireland is an ongoing situation, however, which will take years to solve. To the terrorists it is big business and I don't think that they will give it up just like that. Overall though, our regiment saw it as a very successful tour. I felt that we had achieved something at the end of it.

| Page | Credit | Page | Credit |

| 17 18 19/1 19/2 24 31/1 31/2 38 39 71/1 71/2 | Bert Henshaw Collection Bert Henshaw Collection Bert Henshaw Collection Bert Henshaw Collection Bert Henshaw Collection Bert Henshaw Collection Bert Henshaw Collection Bert Henshaw Collection Barney McMonagle Guildhall Press Blakeway Productions Ltd | 87/1 87/2 88/1 88/2 101 102 106 124 137 143 144 | Barney McMonagle Barney McMonagle Barney McMonagle Barney McMonagle Bert Henshaw Collection Private collection Bert Henshaw Collection Bob Harker Bert Henshaw Collection Bert Henshaw Collection Bert Henshaw Collection |

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||