Drawing Conclusions: A Cartoon History of Anglo-Irish Relations 1798-1998[Key_Events] Key_Issues] [Conflict_Background] Material is added to this site on a regular basis - information on this page may change

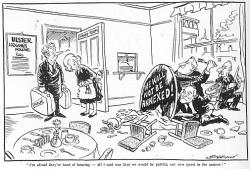

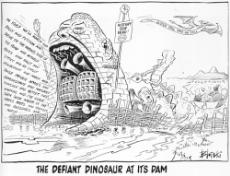

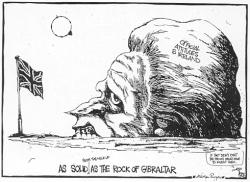

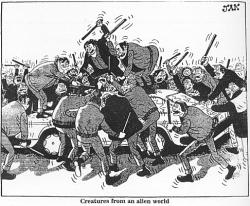

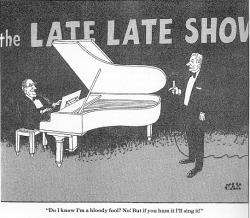

14.21 ‘You were lucky this time ...', Cookson, Sun, London, 13 October 1984 One of the most spectacular and devastating episodes in the IRA’s bombing campaign in Britain occurred in the early hours of Friday 12 October 1984, when a bomb exploded in the Grand Hotel, Brighton, during the Conservative Party’s annual conference. Five people were killed, including one MP and the wife of the government chief whip, while over thirty others were injured. The prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, narrowly escaped injury, as did the rest of her cabinet. British public opinion was outraged at this atrocity, the dreadful reality of which showed just how close the IRA had come to wiping out most of the British cabinet. The bomb had in fact been planted almost four weeks earlier and revealed the increasing sophistication of the IRA’s electronic timing devices. Cookson’s cartoon in the popular Sun tabloid starkly expresses the impact of this attack on the British democratic process by showing the ghoulish spectre of IRA terror slinking away from the scene of the explosion. In a subsequent statement the IRA said: ‘Today we were unlucky, but remember, we have only to be lucky once. You will have to be lucky always. Give Ireland peace and there will be no war.’ Margaret Thatcher immediately responded by stating that ‘the government will never surrender to the IRA’. However, some of her advisers believed that something more than a security response alone was required, and advocated the renewal of the search for a political solution. Despite her rejection of the main proposals of the New Ireland Forum in November 1984, she and her Irish counterpart, Garret FitzGerald, were to sign the Anglo - Irish Agreement almost exactly a year later. 14.22 ‘I'm afraid they're hard of hearing ...', Gibbard, Guardian, London, 16 November 1985 The 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement was an attempt by both governments to bolster constitutional nationalism in Northern Ireland by showing how progress could be achieved through negotiation. This, it was hoped, would reconcile alienated Catholics to the political process and undermine Sinn Féin support. At the same time, the agreement sought to reassure unionists that constitutional change would not happen without their consent. But while many Catholics welcomed the agreement, especially the proposal to allow Dublin a consultative role in northern affairs, unionist hostility was profound and prolonged. One of the main targets of unionist anger was the permanent inter - governmental secretariat at Maryfield, near Belfast, where British and Irish ministers met regularly to discuss certain aspects of the administration of Northern Ireland. Gibbard’s cartoon reflects the depth of unionist opposition to this body. It depicts the occupants of the ‘Ulster Lodgings House’, Unionist MPs Ian Paisley, James Molyneaux and Enoch Powell, preparing to attack the bemused new guest, Garret FitzGerald, to the horror of housekeeper Thatcher. Most unionists perceived the secretariat as the instrument of an interfering Dublin government and the harbinger of a united Ireland. 14.23 ‘The Defiant Dinosaur at its Dam', Blotski, Fortnight, Belfast 8 January 1987 Unionist protests continued throughout 1986, spearheaded by Paisley and Molyneaux under the slogan ‘Ulster Says No’. Blotski’s striking cartoon opposite lampoons this resistance campaign by representing it as regressive and anachronistic. Paisley is figured as a giant dinosaur, fossilised in the stream of history, bellowing dire threats of mass unionist revolt. Behind him lies the UUP monster bearing the head of John Taylor and the tail of James Molyneaux, stoking the inflammatory rhetoric. For all their fierce defiance, however, they have been bypassed by the British political leaders, Thatcher, Labour’s Neil Kinnock and David Steel of the Liberals, who sail blithely on towards the impending general election. Northern Ireland’s primitive political creatures, it is implied, cannot and must not be allowed to impede the progress towards a political settlement. 14.24 ‘"Shoot to Kill" Inquiry’, Garland, Independent, London, 27 January 1988 In 1982 the RUC shot dead six unarmed Catholics in County Armagh, five of whom had alleged IRA connections. This incident led to accusations by the Dublin government and the SDLP that there was a so-called ‘shoot-to-kill’ policy being operated by the RUC and that there had been a cover-up over the killings. In May 1984 Manchester’s Deputy Chief Constable John Stalker was appointed to investigate the deaths. Stalker quickly came into conflict with the RUC Chief ConstableJohn Hermon, who, hebelieved, was obstructing his inquiries. Eventually Stalker was removed from the case as a result of dubious disciplinary charges against him which were later dropped. Stalker subsequently claimed that he was removed from the inquiry because his investigation was about to cause a major political controversy. He asserted that while there had been no official policy to shoot terrorist suspects, special RUC squads had in fact killed these six men and then fabricated a cover-up. The investigation was continued by the West Yorkshire Chief Constable Colin Sampson in 1986. Although his report was not published, on 25 January 1988 the attorney-general, Sir Patrick Mayhew, announced that while there was prima facie evidence of attempts to pervert the course of justice by police officers, there would be no prosecutions on the grounds of ‘national security’. This decision was widely condemned in many circles. The Dublin government protested, expressing its ‘deep dismay’ and on 9 February the European parliament asked Britain to reconsider its action. Garland’s cartoon illustrates the impact of the decision not to prosecute on the credibility of the whole inquiry. There was a strong feeling among many in Britain and Ireland that the truth had been deliberately obscured, and that justice had been sacrificed for raison d'état. 14.25 ‘As Solid as the Rock of Gibraltar’, Turner, Irish Times, Dublin, 9 March 1988 The opening months of 1988 witnessed a souring of Anglo-Irish relations. The decision in January not to prosecute eleven RUC officers as a result of the Stalker/Sampson inquiry was followed a few days later by the London Court of Appeal’s rejection of the appeal of the six men convicted of the 1974 Birmingham pub bombings, despite new forensic evidence being produced. The Irish justice minister said that he was ‘amazed and saddened’ by the decision, and when a young Catholic, Aidan McAnespie, was killed at a British army border checkpoint in County Tyrone in February the Irish government set up its own inquiry into the killing. In March, three unarmed members of an IRA active service unit were shot dead in controversial circumstances by SAS soldiers in Gibraltar. Mairead Farrell, Daniel McCann and Sean Savage were planning to explode a car bomb during a guard-changing ceremony in the British dependency, but for some time had been under surveillance by M15, the Spanish police and finally the SAS. The killings provoked an enormous controversy, with numerous witnesses challenging the official government version of events. Moreover, a number of British newspapers expressed concern that the use of soldiers rather than police was justifying the IRA claim that they were engaged in a war and not criminal activity. In 1995 the families of the three IRA members won £40,000 from the government for a breach of Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights which deals with the use of excessive force. Turner’s cartoon encapsulates the hostile Irish public mood engendered by this series of controversial events. Britain’s intransigent response to the Stalker inquiry, the Birmingham Six case and the ‘death on the Rock’ incident is epitomised by the snarling, gnarled head of Prime Minister Thatcher, rising from the Atlantic like the Rock of Gibraltar itself. The little bird in the corner suggests that British intransigence is ultimately counter - productive in so far as it merely stiffens the IRA’s resolve to intensify their military campaign. Indeed, controversial incidents like the Gibraltar killings tended to increase the flow of recruits to the Provisional movement. The sceptical attitude of this Irish cartoon towards official British government policy contrasts sharply with the generally unquestioning acceptance by most British newspapers at the time. 14.26 ‘Creatures from an Alien World’, JAK, Evening Standard, London, 21 March 1988 On 16 March 1988, during the funerals of the three IRA Gibraltar victims in Belfast’s Milltown cemetery, a lone loyalist gunman, Michael Stone, threw grenades and opened fire on the mourners, killing three and injuring over fifty. Three days later, the funeral of one of these victims, IRA member Kevin Brady, took place in the same area in an atmosphere of heightened tension and suspicion. When a car suddenly drove at high speed into the funeral cortège, many in the crowd thought it was another murder attack. It was in fact driven by two British army corporals, Derek Wood and Robert Howes, whose presence there has never been satisfactorily explained. Although one of them fired a warning shot, the soldiers were quickly dragged from the vehicle, beaten, stripped and then taken to waste ground where they were shot by the IRA. 14.27 ‘Oh, the horror ...', Oisín, Andersonstown News, Belfast 26 March 1988 The deaths had an enormous impact on people everywhere, mainly because the attack had been filmed by television cameras and by army helicopter surveillance. Television footage of the sheer brutality of the corporals’ deaths shocked world opinion, and the picture of a Catholic priest, Father Alex Reid, kneeling in prayer over the semi-naked body of one of the men seemed to encapsulate the tragedy of the Troubles. JAK’s cartoon reflects the prevailing impression of the killers as bloodthirsty savages and captures the incomprehension of most people in Britain that such actions could take place in part of the United Kingdom. The simianised faces and apelike gait of these semi-human attackers resemble the grotesque figures in his infamous 1982 cartoon (see 14.20, p. 294) and, before them, the monstrous creations of Tenniel and Boucher in Punch and Judy. Oisín, by contrast, views the same incident from a republican perspective, and places the events of that day in a wider historical and political context. He shows a crazed and bloodthirsty Margaret Thatcher wearing the cloak of hypocrisy, surrounded by British weapons of war. The use of cs gas and plastic bullets led to the loss of innocent lives in Northern Ireland, while the missile labelled ‘Bulgrano Gotcha!’ refers to the sinking of the Argentinian naval vessel, General Belgrano, during the Falklands War, which resulted in the death of over one hundred Argentinian sailors. ‘Gotcha!’ was the infamous headline with which the Sun newspaper greeted this news. The cartoon questions the legitimacy of British accusations of IRA depravity by suggesting that Thatcher’s government has itself perpetrated acts of horrific brutality in order to defend British interests. 14.28 ‘Do I know I’m a bloody fool?... ', JAK, Evening Standard, London, 20January 1992 In spring 1991 the Northern Ireland secretary, Peter Brooke, after much patient work, succeeded in getting talks started between the British and Irish governments and the four main constitutional parties in Northern Ireland. Although these were soon halted, he had high hopes of resuming them after the impending British general election. In the meantime, however, the worst atrocity of the year occurred near Cookstown, County Tyrone, on 17 January 1992, when the IRA blew up a minibus carrying Protestant workers home from the army base where they were working. Seven men were killed instantly, and an eighth died later in what became known as the Teebane massacre. The horror of the bombing appalled most people in Ireland, especially the Protestant population of the north. Later that evening Brooke appeared in Dublin on one of the most popular shows on Irish television, the Late Late Show, his appearance having been planned in advance as part of a public relations exercise in the south. During the show, however, he reluctantly allowed himself to be persuaded by the host, Gay Byrne, to sing ‘My Darling Clementine’. Unionists were outraged that the Northern Ireland secretary should have shown such public insensitivity within hours of a grave atrocity and called for him to resign. Brooke did in fact offer his resignation, but it was rejected by the prime minister, John Major. JAK’s cartoon overleaf sums up the acutely embarrassing predicament into which a naïve Brooke had allowed himself to be manoeuvred. Byrne calmly looks on as Brooke happily makes a fool of himself. Many people accepted that Brooke was a decent and well intentioned minister who had made a silly mistake, and he received considerable sympathy from both government and opposition MPs for his error of judgement. The incident had damaged his credibility with the unionist population, however, and when Major reshuffled his cabinet after the April 1992 general election, Brooke, to his disappointment, was replaced as Northern Ireland minister by Sir Patrick Mayhew. The Irish television authorities later apologised for the incident.

|

CAIN

contains information and source material on the conflict

and politics in Northern Ireland. CAIN is based within Ulster University. |

|

|

|||

|

Last modified :

|

||

|

| ||